Today’s modern wind turbines seem to repel poetic or artistic engagement. It is difficult to imagine a landscape painter portraying their spare lines and uniform rows as icons of a pastoral idyll, as the windmills of the past often were.

Perceptions of modern wind turbines seem worlds away, for example, from how Robert Louis Stevenson described the windmills of England in 1882:

There are, indeed, few merrier spectacles than that of many windmills bickering together in a fresh breeze over a woody country, their halting alacrity of movement, their pleasant business, making bread all day, with uncouth gesticulations, their air gigantically human, as of a creature half alive, put a spirit of romance into the tamest landscape.

The aspects that struck Stevenson – the motion of windmills, symbols of prosperity, on the horizon – were highlighted a decade before by the French novelist Alphonse Daudet in his depiction of Provençal life:

The hills all about the village were dotted with windmills. Whichever way you looked, you could see sails turning in the mistral above the pines, and long strings of little donkeys laden with sacks going up and down the paths; and all week long it was a joy to hear on these hill-tops the cracking of whips, the creaking of the canvas of the sails, and the shouts of the millers’ men … These windmills, you see, were not only the wealth of our land, they were its pride and joy.

Yet perceptions of windmills have not been uniformly idyllic. Since they first appeared on the landscape of medieval Europe, windmills represented an imposition of the technological on the pastoral. They were, in the phrase of the wind energy author Paul Gipe, ‘machines in the garden’, straddling the boundary of the agrarian and mechanical. Unlike the static technologies shaping landscapes – from cathedral towers or canals in the past, to power lines, solar panels or rows of genetically modified crops today – windmills are constantly in motion. They refuse to passively disappear into the landscape.

With the spread of modern windfarms, the cultural positioning of wind power remains a contentious issue. But the debate is not new: for centuries, the symbolic nature of windmills – as technological monsters or icons of the idyllic – has been open to question. Understanding this debate can help open new avenues for engagement with today’s wind technology.

Though European windmills first appeared as early as the 11th or 12th centuries, there are still clues to how this new technology was initially perceived. In Dante’s Inferno, for instance, when the poet reaches the deepest circle of hell, Satan becomes visible through the gloom. As the ominous figure appears, he is described with a metaphor that would have been growing familiar to many of Dante’s original 14th-century readers:

As, when thick fog upon the landscape lies,

or when the night darkens our hemisphere,

a turning windmill seems afar to rise …

Through the darkness, the devil’s huge limbs are visible like the sails of a windmill pinwheeling on the horizon. To readers whose largest built realities were stable, unmoving church towers or city walls, the ceaseless, arching sweep of a windmill’s arms was no doubt disconcerting to say the least. Later, when Cervantes pictured them as giants in Don Quixote’s imagination, he could gesture to this lingering unease over this most prominent structure on the medieval horizon.

Windmills became integral to communities: structures with names, histories and inhabitants

Besides their visual impression, the first windmills also challenged existing energy infrastructure. Since Roman times, power to mill grain had been confined to water mills and remained the property and protected prerogative of feudal landowners. As the first windmills spread throughout England, they were greeted with resistance by landowners attempting to preserve their ancient rights. Windmills ‘threatened both lucrative old water mill franchises and traditional upper-class privileges,’ recounts the historian Edward Kealey in Harvesting the Air (1987), and ‘offered quick-witted peasants an opportunity to evade manorial regulations, act independently, and become quite prosperous.’ Angry landowners ordered illegal windmills be torn down.

A Windmill near Brighton (1824) by John Constable. Courtesy the V&A Museum, London

Yet eventually this disrupting, disquieting technology became an aspect of the pastoral ideal. Windmills became integral to communities: structures with names, histories and inhabitants. Operating a windmill took skill, care and attention. The miller, who lived in the windmill, was fully occupied with watching the weather, trimming the sails, and keeping the windmill functional from generation to generation – besides providing a vital agricultural role in the community by grinding grain. Ultimately, as the art historian Alison McNeil Kettering has argued, windmills took on the role of ‘cultural signifier’, representing provision and guardianship over a well-run community, becoming familiar icons of ‘pastoral tranquility’ and ‘agrarian idyll’.

As the last generation of millers cared for the last windmills turning in England, their aesthetic value lingered even as their commercial value disappeared. As Stanley Freese wrote in Windmills and Millwrighting (1957):

[N]either photograph nor drawing can capture for my pages the most beautiful of all country scenes; only those who have caught sight of the big white sails of a windmill following one another against a background of dark hills or woodlands, or black canvas sails soaring one after another into an evening sky, can fully apprehend the characteristic beauty of this structure, which differs from all others because it is alive with comely motion, never awkward or ungainly, but blending well with every kind of landscape.

As steam replaced wind in Europe, a new type of windmill emerged across the Atlantic. Whereas European windmills were inhabited structures positioned within the community, the unsettled expanse of the western United States saw the windmill altered to run for decades in isolation, pumping water for farmsteads or for cattle stations scattered across hundreds of miles of arid ranchland. Dozens of models represented a Darwinian response to this environmental challenge: self-lubricating mechanisms, designed to track and spill the wind with counterweights and springs, their complex down-gearing transforming rotary motion into a steady back-and-forth pumping action in even the lightest breeze. By 1889, there were more than 70 windmill factories in cities across the American Midwest. At the European windmill’s peak, there were perhaps 100,000 of the structures across Europe; by contrast, there would eventually be more than 6 million windmills in the US.

Lame Deer, Montana, September 1941. Photo by Marion Post Wolcott, Library of Congress

Unlike the graceful European windmill, the new US variety was considered ugly and ungainly. An American architect insisted that American windmills ‘should be condemned’ as offensive to sight: ‘To see these awkward, spider-like structures dancing fandangos before our eyes disturbs the repose and mars the landscape of our otherwise beautiful homes.’ Worse, another author said the countryside was littered with wrecked windmills, casualties of the failure to maintain or lubricate – this last chore a near-weekly requirement for some of the earliest models. Yet despite these initial impressions, the new American windmill (technically, a wind pump) soon became an icon of the Western settlers themselves: independent, self-reliant, steadily facing whatever storms arose.

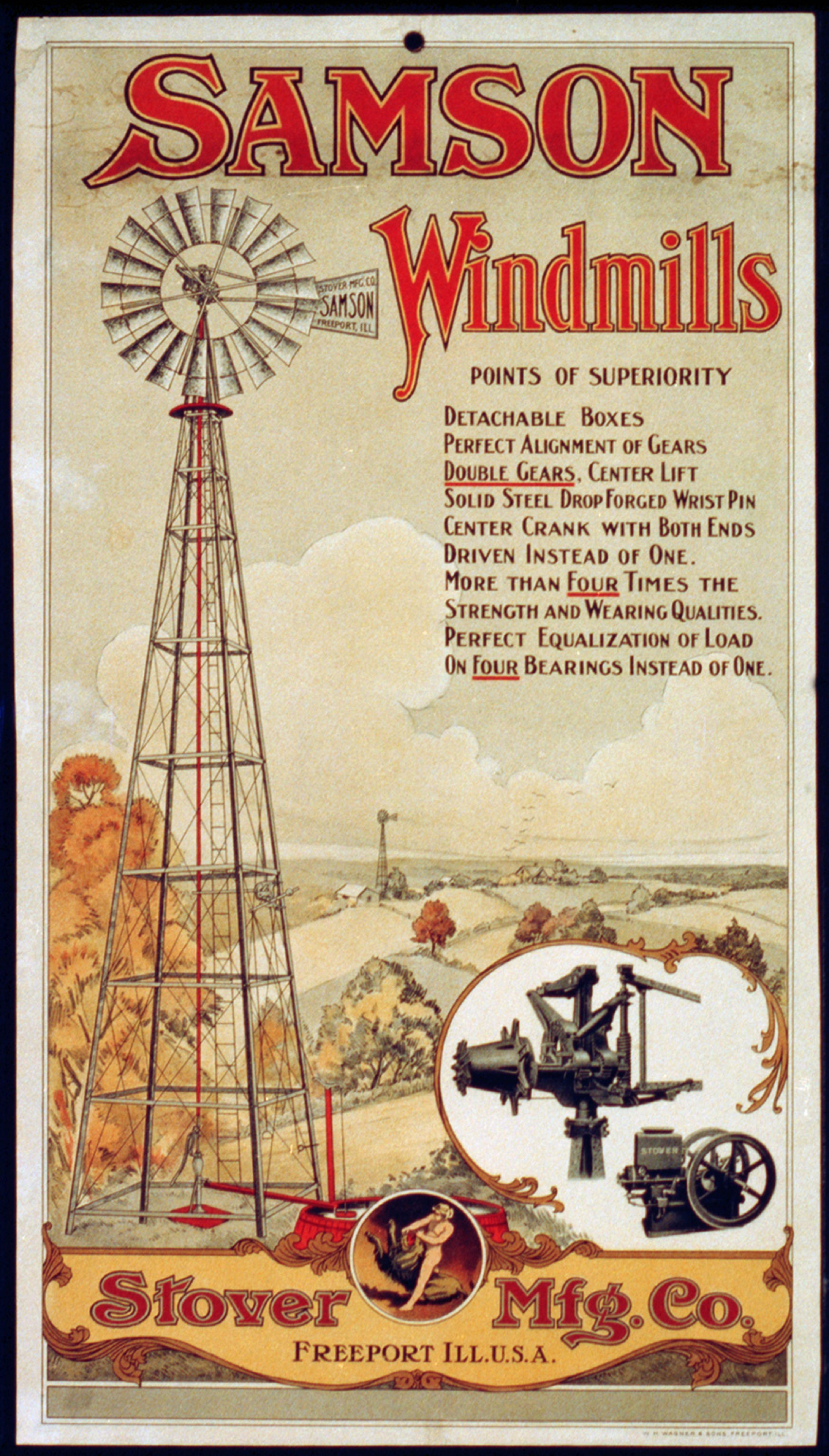

Manufacturers helped cultivate this view of windmills as totems of the American west

A Kansas City Star reporter writing in 1964 captured the feeling of growing up in the shadow of a farmhouse windmill, an experience common to generations of settlers and their descendants. There was:

the gentle sough of the breeze through the fan, the creak of the tower and the rhythmic metallic working of the gears and sucker rod, and finally the steady soft pouring of water into the tank … And then there was a sound all its own: a blade bent by some long forgotten encounter with the wooden tower at each revolution – thump, thump, thump, when the wind was soft and at a machine-gun rattle when a summer storm sent up dust and dead tumble weeds racing across the flat … On quiet nights, for a child awakening in the darkness of a stuffy room, the chipping of the wounded blade against the tower took on a comforting sound, reassuring that this was home, that there was no storm, and that the windmill was pumping water.

Like the European windmill before it, the American windmill was becoming a cultural signifier of a new pastoral ideal.

Courtesy the Library of Congress

In the new commercial context, windmill manufacturers helped cultivate this view of windmills as totems of the American west, presenting them in advertisements and catalogues as part of an idyllic farm landscape. Competition among manufacturers also meant windmill designs became as simple and reliant as possible. Windmills needed to be shipped across the country, assembled hundreds of miles away on the open prairie, and to operate in isolation for years on end. Their buyers needed to own, understand, and service the windmills themselves. The success of this approach is evidenced by the windmills still spinning across the US and the world, with a handful of companies today producing designs that remain unchanged from the 1910s. Like the European windmill, American windmills became pastoral icons, their ceaseless labour – working in the slightest breeze and weathering the harshest storm – a visual metaphor for diligence, independence and patient endeavour.

Today’s massive wind turbines are larger than past windmills by an order of magnitude. The question facing this latest generation of wind technology is more than whether they will be seen as icons of energy independence and sustainability, or simply another extractive industry ‘replicating the exploitative practices of the infrastructures they would replace,’ as the historian of science Nathan Kapoor put it. Rather, the question is whether the social imaginaries available to previous generations of windmills – the chance to become symbols of provision, community or self-reliance – are available to modern windfarms. It is a question playing out, for instance, in debates between farmers who welcome wind turbines and the income they represent and those – often within the turbines’ shadow – who see them as monstrous technological impositions on the landscape.

What prevents modern wind turbines from the sort of cultural integration that European and American windmills obtained? Part of the answer comes by considering wind technologies in light of work by the philosopher of technology Albert Borgmann. In his classic Technology and the Character of Contemporary Life (1984), Borgmann offers his analysis of ‘device’ as both critique and exemplar of modern technology. According to Jesse S Tatum, a device is a technological artefact designed to make ‘a single commodity highly available while making the mechanism of its procurement recede from view’. Our current technological paradigm is the creation of as many devices as possible, from cars to electronics to infrastructure, to make commodities hyper-convenient and abundant.

The problem with devices is that, by design, they are black boxes. Devices, in Borgmann’s treatment, are inaccessible to understanding or engagement. They demand no skill, disburdening their users while, in Borgmann’s words, resisting ‘appropriation through care, repair, the exercise of skill, and bodily engagement’. Devices, whether kitchen appliances or the electrical systems that supply their energy, neither express their creator nor ‘reveal a region and its particular orientation within nature and culture.’ Writing in 1984, long before the advent of smartphones, Borgmann’s analysis is prescient in highlighting how technological devices provide essential commodities such as information, entertainment, energy and food, while simultaneously keeping the means of their production inaccessible and largely invisible.

Impossible to consume the commodity of ground grain from a windmill without ‘invoking or enacting a context’

Despite the abundance of commodities, our interaction with devices leaves us distracted and dissatisfied as our engagement with the world is reduced to ‘narrow points of contact in labour and consumption’. For Borgmann, the solution is not a return to a pretechnological setting but rather to recentre human practices and flourishing around what he refers to as ‘focal things’. In contrast to a device, a focal thing is ‘inseparable from its context, namely, its world, and from our commerce with the thing and its world, namely, engagement’. Focal things represent locality and craft; they engage body and mind, and that engagement requires skill: ‘The experience of a thing is always and also a bodily and social engagement with the thing’s world.’

Focal things invite users to interact with them, giving rise to what Borgmann calls ‘focal practices’ that make the thing part of the broader culture and social structure of the community. The European windmill, dependent in its operation on the skill and care of the miller, in its construction and maintenance on the knowledge and expertise of carpenters and millwrights, and in its purpose on local agricultural practices, was a quintessential Borgmannian focal thing – a nexus of material culture, social heritage and artistic expression. It was impossible to simply consume the commodity of ground grain from a windmill without ‘invoking or enacting a context’.

Likewise, American windmills, though factory manufactured on a large scale, immediately entered the context of homestead or ranch. They were designed to be open and accessible to users for care and maintenance, and the farmer or rancher took ownership and exercised skill in that maintenance and care – learning the idiosyncrasies of each individual windmill. While providing the essential commodity of water, windmills took on additional symbolic and cultural roles, offering a sense of solace, wellbeing and aesthetic pleasure (as evidenced by their reappearance on smaller scales as lawn ornaments across the Midwest and beyond). Both European and American windmills, according to Borgmann’s paradigm, functioned as focal things – technological artefacts that connected their users and communities to both landscape and wind.

Modern wind turbines are designed to fit the device paradigm, providing the commodity of energy or (to the landowner who rents space for their footprint) money, but they fail in a vital respect. No matter how they are isolated from nearby communities or coastlines, their motion keeps them visible on the horizon, even as the other large-scale energy infrastructure devices (electric lines, telescope poles, cellphone towers) fade from view. Their primary mechanism of transforming wind into energy remains impossible to hide. As the growth of sustainable energy continues, more and larger windfarms will be required, and their visible impact will only increase. The tension between wind turbines as disengaging devices and their obvious presence on the landscape will continue. Previous iterations of windmills, however, were not ultimately accepted by making them invisible but rather by changing how they were perceived. Can something similar happen for modern wind turbines, transforming them from devices to something that’s closer to Borgmann’s focal things, and opening a path to richer cultural and aesthetic engagement?

Wind turbines are currently designed and implemented as devices. At least in part for safety and liability concerns, they are isolated even as they remain in view. Wind turbines are, like Borgmann described high-rise buildings, ‘though imposing … not accessible either to one’s understanding or to one’s engagement.’ But this disengagement is one of the main reasons wind turbines are often viewed with such negativity. As the philosopher Gordon G Brittan Jr expresses it, wind turbines ‘are ubiquitously and anonymously the same, alien objects impressed on a region but in no deep way connected to it. They have nothing to say to us, nothing to express; they conceal rather than reveal.’

On the other hand, these modern windmills have many characteristics of Borgmann’s focal things. Focal things, according to Borgmann, ‘are concrete, tangible, and deep … They engage us in the fullness of our capacities. And they thrive in a technological setting.’ By depth, Borgmann means that all of an object’s physical features are significant, something acutely true of precision-designed wind turbines constructed so that each curve and angle generates as little resistance and as much efficiency as possible. Depth means complexity, and complexity can be an aspect of engagement. Yet much of the complex, elegant design of wind turbines that could make them engaging rather than alien remains physically hidden and corporately protected.

An unused turbine blade propped along a country road allows one to experience its scale and scope

Engagement with focal things need not be physical. Besides the handful of skilled workers who design, construct and maintain the turbines (and whose work itself is a point of possible wider engagement, as shown by the reality TV show Turbine Cowboys), most people will not be able to physically engage with these artefacts in any practical way. But education and outreach are powerful forms of engagement largely unutilised by the various actors involved in the creation and maintenance of windfarms. This makes sense within the device paradigm: we aren’t usually invited into engagement with our electrical substations. But if it is impossible to ignore them, education and engagement can help us move toward making wind turbines focal things.

Other avenues of engagement could be as simple as suggested routes navigating drivers or cyclists on public roads through wind farms, allowing visitors to intentionally experience them as part of an aesthetic vista. And though no one should be climbing them, there are ways to bring their physicality nearer the observer. Near my own home, for instance, an unused turbine blade propped lengthwise along a country road allows one to experience a sense of the scale and scope of these artefacts. The experience of locality could be integrated with education: information such as how fast the turbines spin or how much energy they generate from moment to moment need not be obscured or accessible only to experts. These physicalities could instead be ways to engage those passing through. This doesn’t mean expensive interpretive centres at each wind farm (though it could); it might be as simple as signage along the roadway. Science communicators can help here to form bridges between the artefacts and the curious public who watches them along the horizon.

Though a more complicated concern, ownership needs to be considered as well. A deep sense of engagement comes about from artefacts that are individually or communally owned. It was this sense of ownership that allowed US windmills their cultural role and that made European windmills a vital part of their communities. This continues today, as individuals and local communities lovingly restore and maintain these earlier windmill iterations, though they are no longer the means of providing the commodities they once did. The current model of off-site ownership of wind turbines is a powerful factor keeping today’s windmills firmly within the device paradigm.

For Borgmann, ‘the dignity and greatness of a thing in its own right’ – and the stately turning turbines along my Midwestern horizons can certainly have this dignity – is what allows focal things and the practices built around them to ‘gather and illuminate the tangible world and our appropriation of it’.

Borgmann’s device paradigm helps make sense of cultural and aesthetic concerns around modern wind farms, and the history of windmills gives hints of how things might be different. Without efforts of engagement, wind turbines remain inscrutable devices, easy to reduce to uniform, monolithic symbols of extractive capitalism. Unless we try to integrate them into local culture as focal things, they will never be symbols of the landscape like windmills of the past.