An eBay commercial from 2004 opens with a ginger-haired little boy losing his toy sail boat to the tides of the Atlantic at Cape Cod in 1972. Viewers follow the boat out to sea where it faces harsh winds and a terrible storm that sends the boat to the ocean floor, presumably forever. The ad cuts to years later when the boat resurfaces in a net on a commercial fishing boat. In the next shot, the boat appears on a computer screen in front of a ginger-haired adult, his face bearing a look of stunned recognition. A gentle voice asks: ‘What if nothing was ever forgotten? What if nothing was ever lost?’

It is a deeply romantic story at every turn, from the decision to make the lost object an old-fashioned toy to imbuing the laborers on fishing boats with a benevolent impulse to feed nostalgia on distant shores.

When I first watched the ad as a sophomore at New York University, I was moved by the idea of a lost artifact finding its way home through the connective power of the internet. The notion appealed to me as I embraced Facebook in its first year of existence and dutifully updated a DeadJournal to stay connected to my high‑school friends. More than a decade later, I watched it again with a sense of dread: the internet is far less likely to produce a beloved artifact of youth than its embarrassing archive.

‘The internet is forever’ has long been the refrain of neurotics who wring their hands over privacy. But, back in the earliest days of online interaction, we couldn’t conceptualise what forever meant for digital experiences. They seemed ephemeral, intimate. We were blissfully unaware that our little exchanges might one day be part of ‘Big Data’ to be collected, spat out crudely into an algorithm, and monetised. But what we thought were whispers that disappeared into the wind were footprints left behind in soil. That soil was fossilising, preserving a partial archive, hidden until it is not.

Long before we knew that digital surveillance for commercial and security purposes would become the status quo, many of us littered the web with personal material under the impression that we controlled its mobility and visibility (if we considered such things at all). And while tech-savvy adults were the internet’s earliest pioneers, children such as me arrived on the scene within a few short years of America Online (AOL) hitting critical mass in the 1990s.

Armed with a shiny new ‘@aol.com’ email address and blessed with limited parental supervision, I ventured out into the big wild worldwide web for the first time in 1995, at the age of 10. Until AOL Instant Messenger was launched in 1997, my primary tool for connecting to others online was chat rooms, found on the websites for local alternative music stations or fledging entertainment magazine sites. A born adventurer and a blossoming pervert, I regularly pretended that I was a hot and bothered 19-year-old, and lured men away from group chat rooms to private chats where my digital captive and I would proceed to have cyber sex, the clumsy beta version of what would eventually become sexting. My participation was mostly limited to describing a lot of scandalous outfits and giggling hysterically at the very idea of oral copulation.

And though I recall my antics fondly, I feel a twinge of guilt at having ensnared an unsuspecting person into committing what would become a crime, if it was not already one at the time. I figure that all internet users were producing mountains of gossip, inanity and recklessness, but perhaps young people were doing so with more indiscretion. A glance at my search for whether it’s possible to recover AOL chats reveals that I am not alone – neither in my concern that these chats are all stored somewhere in the ether, nor in my disappointment that they might, in fact, be gone forever.

A November 2000 post by a user named ‘Curiousgal’ on Techguy.org reads: ‘I have been chatting on AOL Instant Messaging [AIM] and AOL chat rooms. Are these chats of the last year stored somewhere on my hard drive? If so, is it possible for me to delete them? If so, how? I’m using Windows 98. Please help. Thanks.’

The wisdom that follows this and similar questions across the now-defunct forums was fairly uniform in reporting that AOL did not save user chats but that users could manually enable a feature that would save their chats on their hard drives. AOL’s current help site for AIM (which is still alive) says that chats are stored for a month.

More enterprising youth set about creating websites through such hosting sites as Tripod, GeoCities and Angelfire, where they erected glittery shrines to celebrities, their favourite fantasy books, and even to their own interior lives.

What might we find with a bit of crawling down the lines of connective tissue linking our present digital selves to our pre-SEO digital adolescence? Most often, an email address serves as the bridge between our digital present and our past: we are forever a few reset passwords away from breaking the seal on the tombs of our former online incarnations. In my particular trajectory, an AOL account begat a Yahoo account which begat a Gmail, with a handful of detours into work and school domains. My handful of passive memberships in Yahoo groups dedicated to celebrity worship and my many abandoned attempts to build a blogging empire are all linked to this account, but I am locked out of it by long-forgotten security questions and broken links.

‘A lot of people see what they put online as meaningless ephemera. A shocking number of people don’t even care about keeping their own content’

When some friends from high school unearthed our community of DeadJournals from the early 2000s recently, a flood of memories came back of our semi-ironic fascination with mall goth culture and an exaggerated pride in the local mythologies of Rancho Peñasquitos, my suburban enclave in northern San Diego. My amusement at our juvenile usernames and our bumbling grasp of ironic humour soon gave way to panic that future employers or partners might be less amused, were the enthralling narratives of my 18th year to wash up on my Google search.

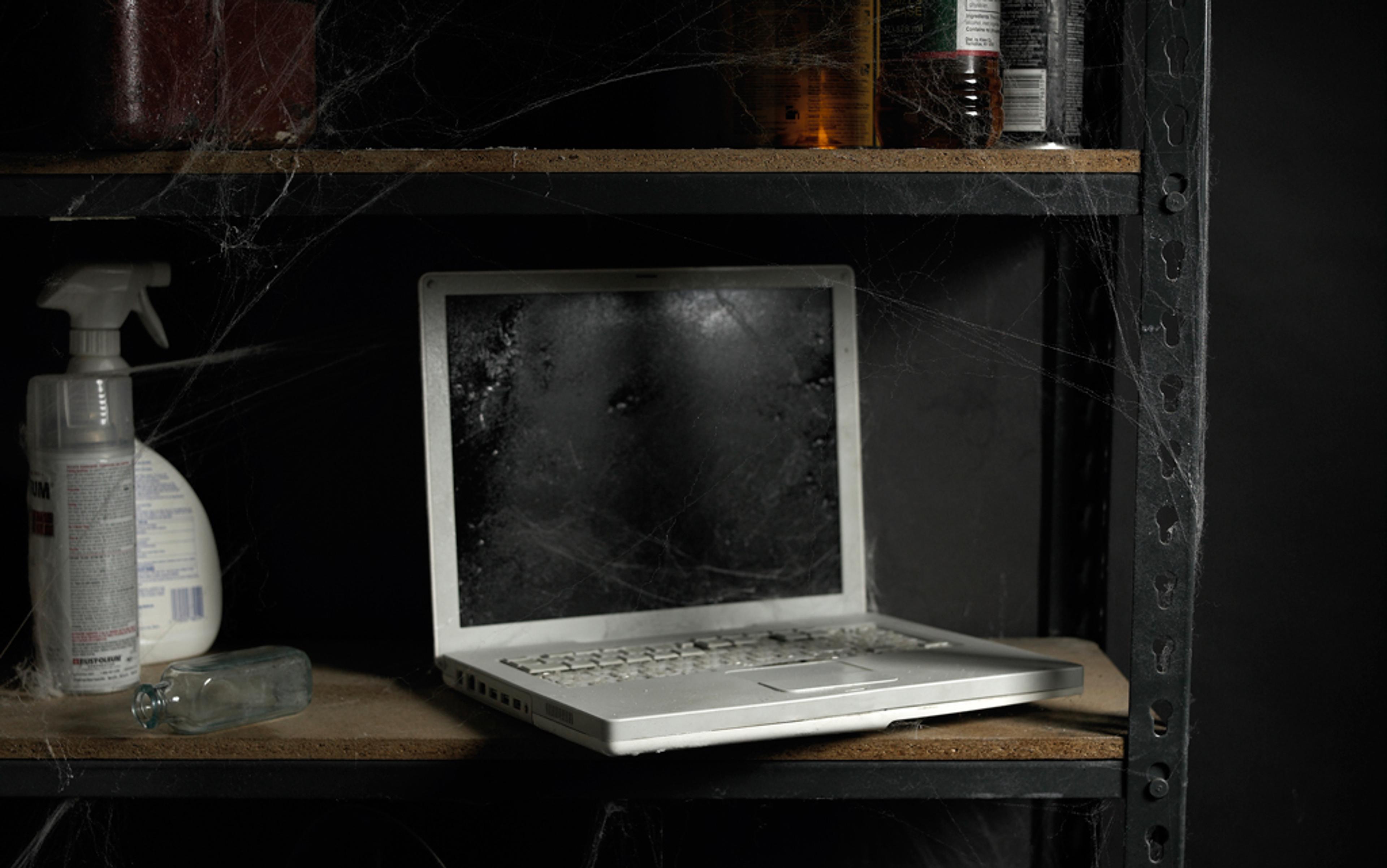

I Googled my own DeadJournal’s tagline – ‘Welcome to Hell: Skellington Has Been Waiting For You’ – and was relieved to find zero matches. All DeadJournal users had their own profile page where they could list their email address and an external website. I’d linked to a site created with five friends, a chronicle of the inanity and adventure of a memorable summer. To my relief, the link was dead. Yet my mind returned to the toy boat at the bottom of the ocean, out of sight but not truly lost. If there were still forums from 2000 discussing the status of AOL chats, and DeadJournal links readily available through Google searches or a quick URL search, did anything of my digital childhood remain beyond the grasp of Google?

I asked Michael L Nelson, a computer scientist at Old Dominion University in Virginia, how likely it is that someone, or something, could follow my trail back to find the comments and profiles I’d flung across the internet in the 1990s and early 2000s. ‘It would be possible but surprisingly difficult because most of those pages are dead now, so we can’t use Google to discover them,’ he told me. Nelson’s research on digital preservation and how to better archive the web reveals that an overwhelming amount of data from the first several years of the internet are gone forever, a relief to my neuroses but a stumbling block to my morbid curiosity. For every person like me who is unduly preoccupied with their digital footprint, there are several more who don’t care what’s online, or whether it stays there. ‘A lot of people see what they put online as meaningless ephemera. A shocking number of people don’t even care about keeping their own content,’ Nelson said. It is precisely this apathy towards keeping the content we created that causes many of us not to delete our content but to abandon it, leaving it unsupervised.

That is how the US writer Christine Friar became reacquainted with her high‑school self. A few years ago, she received an email from a former classmate who had Googled herself and found a blog hosted on Tripod that Friar created for a freshman English class and occasionally updated in later years, confident that her teacher was the only person with the URL. This former classmate found her own name in a post by Friar that was disparaging of another girl and made an off-the-cuff remark about the girl’s friend having a lisp. The girl in question was now a candidate for a prestigious scholarship, and asked Friar to remove the post so that the search committee wouldn’t find it.

‘In a pre-Google America, I used her full name without even the remotest suspicion that it might come back to haunt either of us in any way,’ Friar told me, noting that she didn’t even remember having negative feelings about the girl during high school and must have been just venting particularly unkind feelings that day. ‘It still makes my stomach turn in that very specific, childhood‑guilt‑way when I think about it. Fuck. You never want to remember yourself as someone capable of something truly shitty, but that was one thing I did that was truly shitty,’ Friar said. ‘Google remembered it way better than I did.’

And when Google does not remember something, it is quite possible that any of the growing number of digital archives have remembered at least part of it. The Internet Archive remains the most comprehensive of these collections. Started in 1996 by people with the foresight to recognise that the internet was indeed a dynamic and growing cultural artifact worthy of preservation, it has influenced the creation of similar initiatives around the world. Though most viewed their activity online as little more than digital waste, others saw an unprecedented new historical record emerging. ‘We acknowledge and take into account the right to be forgotten, but our purpose here is about the right to be remembered,’ says Helen Hockx-Yu, who is head of web archiving at the British Library in London.

Invoking a 1622 mandate in English law, all material published online from a ‘.uk’ domain and all material produced by British citizens became required by law in 2013 to submit that material to the Legal Deposit Libraries working to systematically archive the British internet. ‘The usual argument is: Why would a national library be interested in collecting the whole internet? It’s all people talking about sex and cats, it’s rubbish!’ said Hockx-Yu. ‘We don’t make value judgments, we follow our mandate and preserve the web for heritage purposes.’

Sifting through the remaining fragments of our site was like rereading a book I knew well with the pages unnumbered, out of order and half-missing

Hockx-Yu’s team works with other archives around the world to build a more comprehensive archive of our digital history. A tool born of this effort is Time Travel, a site where users search a domain name and date, and the service retrieves ‘mementos’ from more than a dozen major digital archive projects. I took a breath and manually entered the URL to our once-dazzling shrine to suburban antics: six animated avatars appeared on the screen, our representations clad in peasant tops and denim, sporting long hair that’s practical only on the impossibly young and moderately vain. Each of our names was followed by an exclamation point, as if ‘Alana!’ and ‘Kate!’ were celebrities requiring no further introduction.

Sifting through the fragments that remained of our site was like rereading a book I knew well with the pages unnumbered, out of order and half-missing. The image links we had used as a menu were all broken so I had to click on identical icons of a half-torn paper to see if the page had been rescued from the digital abyss. The first intact page I found was our faux-newswire service ‘The Associated Mess’ where we mixed real updates from Michael Jackson’s ongoing legal troubles with flourishes such as our friend Meghan becoming the unexpected heiress to the Fruity Pebbles fortune. In the multi-layered universe we had created to reign over, the self-professed ‘King of the Goths’ whose blog we checked dutifully was as much a celebrity as Britney Spears. We sold fan T-shirts and beer mugs with the motto: ‘Get Krunk and Eat Burritos.’

More than a decade later, I cannot sufficiently detach from the fond memories of this world to discern if it was genius performance art or a charmless collective narcissism. The possibility that it’s the latter makes me grateful that this artifact is, at least for now, impossible to find using Google. But fortunes aren’t made using what is possible or even probable now as metrics for what can or should be possible later.

Nostalgia for its own sake is also being successfully commodified and repackaged, so it’s not hard to imagine that there are others who’d love to unearth such sites. The meteoric rise of BuzzFeed (where I worked for several months from 2014-2015) can be linked in large part to its capitalising on nostalgia, with posts such as ‘50 Things That Look Just Like Your Childhood’ bringing in more than 16 million views. Instagram’s raison d’être is essentially to make your present look like your past. At the same time, various archives around the world have spawned nostalgic projects, such as One Terabyte of Kilobyte Age – a research blog about the massive archive of GeoCities sites with an accompanying Tumblr featuring automatically generated screenshots of the now-defunct sites tagged in a way that makes them discoverable in search engines.

It would be reasonable to argue that fretting endlessly over this disjointed bundle of artifacts from our digital adolescence is a waste of energy when corporations are silently pillaging nearly every interaction we now have online for an opportunity to turn it into profit later. ‘Corporations don’t make money from putting your information on the web and embarrassing you. They want to use that information in algorithms to see what we want to buy,’ says Eric Posner, a professor of law at the University of Chicago who has written on the ‘right to be forgotten’, made law by the European Court of Justice in 2014. Posner was just one of the experts I interviewed who argued that the commodification of personal humiliation was not an especially compelling business prospect for any of the corporations currently housing all of this data. But intentional malevolence is hardly a requirement for corporate use of our digital histories to embarrass or otherwise harm us: a bad algorithm on Google Photos made it tag African-Americans as gorillas, while the too-good-at-its-job algorithm steering Target’s marketing mail predicted and outed a teenager’s pregnancy.

‘The real nightmare would be if someone bought all of your information and created a biography of the most intimate details and highlights,’ Posner said, noting that even non-digital files and images could easily find their way online. A quick tag by facial recognition software and searchable text could link the legal identities of people who had conscientiously avoided a digital footprint. It does not take a particularly dystopian imagination to think about future searches not as static pages but as dynamic multimedia experiences. Such aggregations might mirror the ill-conceived ‘Year in Review’ feature that Facebook rolled out in 2014, which inadvertently highlighted family deaths and homes reduced to ashes alongside fond memories, all curated from material scavenged from across decades and borders without our knowledge.

Whether a person would delight in the movie of her life or be humiliated by it might be determined less by her predisposition to sharing online than by how thoroughly the record of her life was digitised, with or without her consent. A recent investigation by The New York Times found that 85 of the top 100 websites in the US had terms of service stipulating that their consumer data could be sold if the company was sold, without any attendant consumer protections. In light of this, it might not be especially long before we find out what such experiences look like. For those who grew up online, it might be the exact ‘50 Things That Look Just Like Your Childhood’.

‘They don’t necessarily have an immediate way for turning your data into profit but they collect it because they see it as potentially valuable’

But for kids growing up online today, this is not a potentiality as much as a compulsory exercise. Even before they’ve opened their eyes in the world, their ultrasounds have been broadcast on Facebook. Their faces are recognised by software with an almost 87 per cent accuracy rating before they’ve learned to smile for cameras. Some parents have reserved their children’s social media profiles for their future use, perhaps overestimating the longevity of these channels. Children are expected to launch and maintain websites for school projects. Five years ago, it was a dystopian horror moment for a baby to touch a television screen and expect it to react; now this is reality. And every last touch is a data point that can be bought, sold, packaged, resold, ad infinitum.

With all of this fresh data at the disposal of corporations, for better or worse, our ancient histories on GeoCities and DeadJournal and AIM might appear worthless to profit-seeking entities. But in an economy that views data as inherently valuable, any number of creative impulses or accidents might breathe commercial worth into this archive. ‘These firms don’t necessarily have an immediate way for turning your data into profit but they collect it because they see all of it as potentially valuable, even if they don’t know how yet,’ says Jacob Silverman, a frequent critic of digital surveillance and the author of Terms of Service: Social Media and the Price of Constant Connection (2015). As corporations start collecting data on younger and younger people to predict the adult consumers they’ll become, it stands to reason that tracing their profiles backwards in time to build a lifetime trajectory of their habits has potential value. In April, Google made it possible to download your entire search history in a few clicks, ripping years’ worth of searches from their contexts into data points – a stark reminder of how crude our digital shadows can look.

One particularly crude Google search became the talk of my social circle a few years ago when an acquaintance found ‘anal fisting blood’ in her partner’s search history. Those who were friendly toward him had benign explanations, but my own conclusion was that he obviously wanted to see pornography featuring a bleeding anus with a fist in it. Yet when I discussed it with others who don’t know him, the hypotheses varied significantly. One thought it could have been a speculative enquiry that could, at best, have been prompted by precaution and, at worst, simple curiosity. Another wondered if the search was an attempt to find a home medical remedy after an incident involving all of the search terms. Who among us hasn’t Googled a medical symptom, after all?

But devoid of context and intent, the raw data of our Google searches is, well, raw. The whole point of the internet was for people to see others and be seen by them. It was a correction for our retreats to the suburbs from once visible and connected communities. We must not lose sight of that objective for fear of becoming data points.

At the intersection of the critical effort to preserve our digital history and the more nefarious impulse to commercially exploit it are formerly private citizens coming to terms with a shifting paradigm in how we understand and control our past, present and future identities. ‘Our digital shadows reflect us but aren’t us, and so we shouldn’t let them define our experience in the world,’ Silverman recently noted in a presentation at Google, noting that data should not be mistaken for actual knowledge. A baby’s life is not the assortment of haphazard touches on her mother’s iPad or the sum of her photos on Facebook. A teenager is not his Instagram direct messages and his pornographic curiosities and his Reddit threads. My acquaintance’s partner is not an anal outlaw. Christine Friar is not an eternal mean girl. I am now only reasonably young and moderately vain.

The ‘About’ page on Time Travel is prophetically instructive for how we might cope with discoveries, made and yet unmade, about our digital pasts. Because the archiving technology captures only snapshots of a site at a given time, results might not be an exact replica of the site as it was. As I learned from the fragments of our site, things such as embedded media might be missing and scripts are unlikely to work. After all, a toy boat is hardly its former self after a lifetime at the bottom of the sea. No matter how intact an archive, it can never fully reconstruct the texture and completeness of the original memory. It warns readers about what might be missing or different from their archived sites and notes: ‘In short, the past may not look perfect. But then again, did it when it was the present?’ before mercifully moving on to a new section too quickly for us to consider an answer.