I stepped into the dark of the ramshackle hillside temple. It was a hot day, and the climb had been steep. There were no other tourists around. The only people I passed on my way up the mountainside steps were two pious old ladies, pausing to catch their breath as they struggled through the afternoon heat.

Inside it was cool, the air fragrant with incense. To one side of the door was a table, and behind the table sat a small, neat man in the robes of a Daoist priest. A handwritten sign in front of him announced that temple entrance was two yuan (20p). I paid my fee and he smiled. ‘Welcome,’ he said. I peered into the dark, where deities and mythological beasts clamoured for attention on the painted walls.

I had visited other temples elsewhere in China, in larger cities such as Beijing, Guangzhou and Wuhan; but there I had blended in among the hopeful devotees and noisy tourists. Here, on the other hand, I was on my own, and felt somehow out of place, unsure how to conduct myself. The priest, however, was in a chatty mood. ‘Where do you come from?’ he asked me in Chinese.

‘England,’ I told him.

He smiled. One of his front teeth was missing. ‘What are you doing in China?’

I told him I was writing a book.

‘A book about China?’ he asked.

I hesitated. I had heard the old joke several times now. When foreigners come to China for a month or two, they go home and write a book. When they have been there for several months more, they write an article. If they have lived in China for more than a year, they end up writing nothing. I was in China for only a couple of months. I hesitated about what to say, then I decided I might as well tell him. ‘It is about the I Ching,’ I said. ‘I am writing a book about the I Ching.’

I was in China in pursuit of an obsession that, among certain of my more sober-minded and rational friends, was the cause of some alarm. For the previous few years, I had been increasingly preoccupied by that strangest of books, the Chinese Book of Changes or I Ching. In the West, the I Ching is mainly known as a divination manual, found on shelves alongside books about tarot cards, crystal healing, reiki, and contacting your angels, a part of the wild carnival of spurious notions that is New Age spirituality, that great tide of unreason against which the prophets of scientific rationality protest in vain. I knew the arguments against the I Ching: divination doesn’t work, it belongs to the realm of prescientific superstition, it is a primitive attempt to tame the uncertainty of the future. I had heard these arguments many times, and they made sense to me; and yet there was something about the I Ching that continued to fascinate me, something that — the more I studied it — could not allow me to dismiss this book so lightly.

My interest in the I Ching had begun several years before, neither as a fascination with Chinese culture, nor as a mystical concern with divinatory practices, but instead in the course of a rambling and idle conversation with a friend. It was 2006, and I was casting around for a fresh writing project. My first novel was due out in the following year. I wanted something new and substantial to work on, but I had no clear sense of direction. At some point during our conversation, we found ourselves talking about the taste for astrology, tarot cards and other forms of prognostication. I was happily pouring scorn on these practices, protesting at their unreason, when my friend interrupted me. ‘Perhaps,’ he said, ‘it is not about predicting the future.’

‘What is it about, then?’ I asked.

My friend shrugged. ‘Perhaps it is about imagining new possibilities.’

I was momentarily silenced. ‘Perhaps,’ I said. Then the conversation moved on, but the thought stuck with me. I was in need of new possibilities. And, after all, hadn’t Italo Calvino, a writer I loved, played with tarot cards in his book The Castle of Crossed Destinies (1973)? So, a few days later, I went to the bookshop, made my way to the Mind, Body and Spirit section, and tentatively picked up a copy of the I Ching: Or Book of Changes, first published in 1951 in a handsome red-and-black jacket, and now in a Penguin edition, with Richard Wilhelm’s German text translated by Cary F Baynes and the rather flaky foreword by Carl Jung.

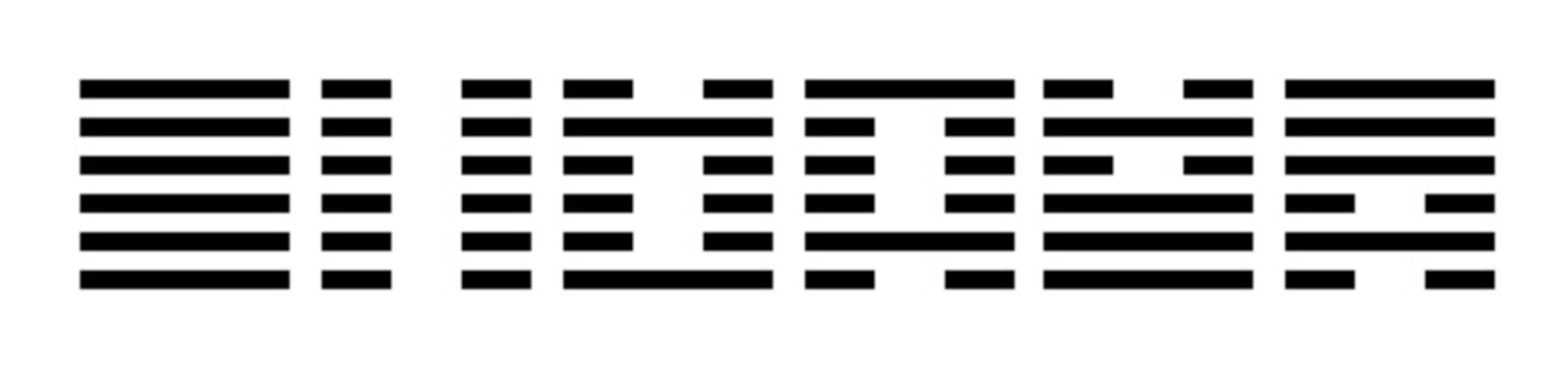

I had come across the I Ching numerous times before on the bookshelves of friends, and had even tried to read it on occasion, but always given up, frustrated by the thickets of obscurity it presented. As I stood in the bookshop flicking through the I Ching, my knowledge of the book was fairly rudimentary. I knew that it was a divinatory text, divided into 64 chapters, with each of these chapters headed by a six-lined symbol, referred to in English as a ‘hexagram’ and in Chinese as guaxiang. I knew that each of the hexagrams was associated with a number of prognostications, and that the book was often put to use by tossing coins or sorting yarrow stalks, to randomly derive a hexagram made up of broken and unbroken lines.

There was a pleasing mathematical completeness to this series of symbols. Six-lined figures, with each line in one of two states, meaning that there were two to the power of six possibilities in all, or 64. Associated with these hexagrams were divinatory statements that were often astonishingly obscure and laconic: ‘Flying dragon in the heavens. It furthers one to see the great man… When there is hoarfrost underfoot, solid ice is not far off… Bites through tender meat, so that his nose disappears… The wild goose gradually draws near the tree. Perhaps it will find a flat branch. No blame.’ Finally, I knew that the I Ching had touched almost every aspect of Chinese thought — from philosophy to statecraft, from music to medicine, and from astronomy to painting, and that on account of that alone, it should be counted as one of the most influential books in the world.

In the weeks and months that followed, I started getting to know the I Ching better. As I did so, I slowly pieced together the strange tale of its place in history: the connection with oracle bone divination in the Chinese Bronze Age; the philosophical commentaries dating to the third century BCE that forever sealed its place as a central text for Chinese thought, securing the book’s far-reaching influence in all corners of Chinese life; and its eventual arrival in the West, via the Jesuits and the German philosopher G W Leibniz, through 20th-century psychoanalysts, esotericists and hippies — via Bob Dylan, John Cage, Philip K Dick and Raymond Queneau, all of whom made use of the book — down to the present day.

It was in this way that I found myself becoming a diviner. A couple of days after getting the book home, for the very first time I took three coins — twopence pieces seemed to be suitably unostentatious — formulated a question, and went about the ritual of casting my first hexagram on the basis of each toss of the coins, thus putting my foot on the slippery slope that would lead first to learning Chinese and, eventually, almost inevitably, to China.

My relationship with the I Ching was complex from the very beginning. Despite repeated re‑reading of the text, in translation and later in the original Chinese, I have never come across anything that looks much like wisdom. Meanwhile, on the internet, whole armies of crazies advanced their theories about the book: that it coded the deep structures of human DNA; that it provided mathematical proof of the Mayan prophecy of the ending of the world; that it might hold the secret to that holy grail of the physicists, a Theory of Everything. And when I read these things, I found myself thinking of the 20th-century British Sinologist Joseph Needham, who said that the I Ching was nothing more than a massive filing system for pigeonholing novelty and then doing nothing more about it. The I Ching seemed to adapt to any purpose whatsoever.

I felt myself descending into a realm of unfettered lunacy, stumbling across increasingly bizarre claims made on behalf of the I Ching; and yet on the other hand the book seemed, bafflingly, to work. I divined for new hexagrams and new stories, tossing coins or sorting yarrow stalks, sat at my desk with a stick of incense burning, and the longer I did so, the more the stories continued to multiply. I was caught between profound unease at the sheer unreason of what I was doing, and the fact that the I Ching so often bore rich fruit in new thoughts, ideas and images.

So, in 2010, I travelled to China to get to the bottom of things. There, covering thousands of miles by train and bus, I set about trying to establish once and for all what this book was about. In Tianshui, I made offerings in the temple of Fuxi, the legendary originator of the I Ching; in Shandong and Hong Kong, I spent time discussing divination practices with philosophers; between Beijing and Guangzhou, I endured an uncomfortable 26-hour train journey in the company of a deranged tattooed diviner who talked the entire time; and along the way, I accumulated books and articles that I sent home in large, unwieldy packages. It was towards the end of my trip that I found myself in the company of the friendly Daoist priest in that hillside temple, and there the thought came to me: ‘Now, perhaps, things will become clear.’

I began to wonder if attempting to understand the I Ching in terms of understanding the I Ching was to risk misunderstanding the I Ching

The priest pushed his entrance-fee sign to one side, opened a drawer and took out a notebook, tearing off a page. He took a biro from his pocket and smiled at me. ‘I will explain everything,’ he said. Then he started an impromptu lecture. As he talked, he scribbled complex diagrams and notes on the page. He told me about Fuxi, about hexagrams and their constituent three-line trigrams, about the pole star and astrology, about philosophy and metaphysics, about the Hetu or the River Map, which explains the relationship between the eight trigrams, and about the wuxing or five phases of wood, fire, earth, metal and water, and its relationship to the numerological magic square known as the Luoshu, or Luo River Book. I leant forwards, occasionally asking him to repeat something, trying to look intelligent; but very quickly I found myself lost in thickets of philosophical and linguistic difficulty. I had read about all this stuff countless times, but I have never had the kind of mind that could keep track of complexity. This makes me a poor student of esoterica.

As the lecture proceeded, a crowd started to gather, because in the most populous nation on earth, crowds are easily summoned. The two old ladies whom I had passed on my way up the hill now stepped into the cool of the temple and grinned wildly to see the foreigner talking with the priest. A family appeared from somewhere or other, the children peering at me in fascination. Three or four others also congregated behind me. As the priest continued to scribble various astral configurations and hexagrams and mystical diagrams, all annotated in a spidery handwritten Chinese, a debate began to take hold among the onlookers. The foreigner doesn’t understand! Yes, he does! No, look, he clearly doesn’t have any idea what the priest is talking about. But I heard him speak Chinese! Ah, these foreigners, all they can say is ni hao, that’s all. No, I distinctly heard him speak some Chinese! A few words, perhaps, no more. What about Dashan, the Chinese TV celebrity? Dashan is a Canadian, and he speaks Chinese. Yes, but this guy is clearly not Dashan.

With the debate behind me, and the priest in front of me spiralling ever deeper into metaphysical complexity, I felt the beginnings of a headache; but at last the lecture came to an end, the priest folded up the paper and handed it to me. I put it in my breast pocket, where later, while hiking up another nearby hill, it would become unreadably drenched with sweat. ‘Now you understand the I Ching,’ he said confidently. ‘Your book will now be very interesting.’

I thanked the little old Daoist. He chuckled as he shook my hand. Then I stood up and smiled at the small crowd that had gathered behind me, and I scuttled into the darkness to nurse my headache and get myself some peace.

Now you understand the I Ching, he said; but in truth I understood no more than I had before. The I Ching has always had the curious quality of becoming more baffling the more I have found out about it. While I knew an increasing number of facts relating to the I Ching, as time went on I was not sure that I actually knew the I Ching itself any better than when I started out. By the time I flew home, I felt even further away from understanding the I Ching than at the outset.

It was only after my return to the UK that I began to wonder if attempting to understand the I Ching in terms of understanding the I Ching was to risk misunderstanding the I Ching. In other words, although we are accustomed, in this information age, to treat books only in terms of the information that they contain, what is most compelling about the I Ching is not so much the promise of some secret, hidden, innermost meaning. Instead, what is most striking is the very real and concrete impact the book has had upon the world through the centuries.

Meaning nothing, containing the seeds of countless possible meanings, the I Ching is the space at the hub that allows the wheel to turn

Undeniably, the I Ching has been one of the most breathtakingly productive of books, a book that has put its stamp on some of the greatest philosophers, poets and writers in Chinese history, that gave Leibniz sleepless nights, that fired up the creative juices of the likes of Dylan and Philip K Dick. A book this productive had to have something going for it. The only question was, what? So, more recently, I have started to ask a different set of questions about the I Ching. I am no longer so worried about what the book means, about what wisdom, if any, it imparts. Instead, I have started to content myself with asking about what it does. In fact, I have come to suspect that perhaps the book has no wisdom to impart, that perhaps it means nothing whatsoever, and it might be in this that it is possible to find the secret of its power. Meaning nothing, the seethe of images — dragons and hoarfrost, migratory geese and ice — nevertheless contains the seeds of innumerable possible meanings. It is like a ring doughnut: empty in the middle, but with the meaning around the outside. But, of course, there cannot be a ring doughnut without a hole — or to paraphrase the passage in the ancient Chinese text the Laozi, it is thanks to the hole at the hub that the wheel turns.

After seven years, the book I set out to write is complete. I have written 64 stories, with commentaries, each based on a hexagram of the I Ching: stories about gods, bizarre machines, archaeologists and kleptomaniac pensioners, non-existent rulers, fox-spirits, inventors, and infernal bureaucrats. Like the I Ching itself, this book of changes that I have written is a strange beast, a little too strange perhaps for any wholly sane publisher to take a risk on. But long ago, this project stopped being about writing this one book. So much else has followed from my long tussle with the I Ching: five years of studying Chinese, visits to hillside temples in China, innumerable new stories and fresh thoughts, a multiplication of projects, possibilities and friendships, and new scents to follow.

Perhaps most surprisingly of all, although my own book of changes is close to an end, I still find myself turning to the I Ching for guidance. I do so not because the I Ching provides me with fresh certainties or with off-the-peg wisdom, but rather because when I put the book to work it tends to give me better uncertainties. The 12th-century poet and scholar Yang Wanli once wrote: ‘The profound implications of the Book of Changes are what plunges people of the world into doubts and makes them think.’

Sitting with the coins or yarrow stalks in my hand, going through the ritual of asking the I Ching a question, I am not looking for some irrational mystical guidance. Instead, I am looking for a release from the prison of competing certainties, a way of letting loose the simmering doubts and confusions that accompany all thought, so that I can take advantage of their creative richness. In other words, I use the I Ching not as a certainty machine, but as an uncertainty machine. Dissolving false certainties, it integrates the fact of unknowing into the fabric of my thinking, opening me up to hitherto unimagined possibilities, scattering the monotony of my either-or dilemmas into a myriad of forking paths.

The world we live in is very different from that in which the I Ching first arose. We have access to an astonishing array of tools and algorithms and banks of data that help in predicting probabilities for the future. Nevertheless, the world remains more vast and extensive than all of our data and all of our algorithms. Uncertainty is not just an adventitious fault that can one day be eradicated. It is also a part of being a human, with limited knowledge, in an endlessly complex world. And given that we will never have the complete knowledge to which we might aspire, we must always act in the twilight between certainty and uncertainty, between knowing and unknowing.

This is where the I Ching seems to me to be extraordinary: in its ability to multiply uncertainties, in its demonstrated efficacy — whether by accident, by design or by long evolution — to be so exquisitely productive of new thoughts, for more than two and a half millennia. Meaning nothing, containing the seeds of countless possible meanings, the I Ching is the space at the hub that allows the wheel to turn on its axle. And if I still use this weird, ancient divination manual, it is not because I want to flee from reason into the comforts of irrationality, nor is it because I believe the book contains a deep ancestral wisdom. Instead, it is because the I Ching repeatedly prompts me to go beyond false certainties and to create new and unexpected possibilities. In this way, divination might not be the enemy of rational thought but could be a means to its fuller flourishing.