The American economy has always relied on household borrowing. Since before the founding, the colonies had been ever short of metallic currency. Our 18th-century forebears substituted credit for cash. They bought goods ‘on account’, borrowing to buy time until the harvest came in or some other windfall enabled them to repay what they owed.

The 19th-century shift from agriculture to industry brought many American workers predictable wages and fixed salaries. Industrial businesses – selling sewing machines, pianos, home appliances, and especially automobiles – developed novel credit arrangements to transform steady paychecks into steady repayments. Instalment credit enabled consumers to purchase expensive durable goods with a small down payment, followed by weekly or monthly payments thereafter.

In cities, department stores refined another form of borrowing: the charge account. These accounts granted affluent consumers a fixed line of credit, which they repaid monthly without paying interest. Like instalment credit, charge accounts existed to sell goods, rather than generating profits from lending as such. Charge accounts made credit convenient, encouraging consumers to buy more.

Convenience came in part through a new link between credit and identification media. Stores issued charge tokens and later charge plates – fobs and metal cards that carried consumer account information – granting affluent consumers the prestige of recognition in cities full of strangers.

Mass consumer credit greased the wheels of mass production. In the early 20th century, proponents praised a virtuous lending cycle. Credit generated consumer demand; which encouraged industrial investment; which led to economies of scale, lower costs, and more industrial work; finally encouraging further consumer demand. Critics worried that consumers, having committed future income to present consumption, would have no future buying power to turn the wheel the next cycle, or the next. ‘Larger and larger doses of the stimulant must be injected merely to prevent a relapse,’ two prominent critics warned in 1926.

The Great Depression ended the debate. The 1929 stock market crash stalled credit buying. Consumers worried. They waited. They postponed credit purchases – a month, two months, three. Individual delays, in the aggregate, froze the economy. Without credit purchases, factories had fewer orders. With fewer orders, factories idled and laid off workers. Unemployed workers cut spending further. They did not borrow to buy. They did not buy at all. The virtuous credit circle that turned in the 1920s shuttered and stopped in the 1930s.

Policymakers took an unexpected lesson from this experience: the United States’ industrial capacity had been built to run on a steady fuel of consumer borrowing. If private lenders would not provide that fuel, New Dealers reasoned, the federal government should.

The New Deal has many conflicting legacies but, from that point forward, federal policy unambiguously supported a political economy with household borrowing at the centre. Federal lending programmes legitimised credit buying by aligning it with national economic priorities of stable employment and steady growth.

Those national priorities changed course when the nation shifted from recovery to warmaking during the Second World War. Policymakers wanted consumers to save, not spend, a policy the US Federal Reserve pursued through firm controls on consumer credit. Government controls encouraged credit innovation, first to circumvent the rules, then to comply with them.

Policymakers initially targeted instalment credit, which consumers used to buy durable goods like cars and home appliances. Retailers, still eager to generate sales, modified their unregulated charge account plans to enable consumers to pay over longer periods of time. Charge accounts gained the now-familiar 30-days interest-free period, with interest charged monthly on the remaining balance.

Fed officials clamped down on regulatory avoidance, prompting businesses to invest in information technology that would help them stay within the rules. Retailers needed to maintain thorough records of their customers’ credit activity and to halt credit sales that violated Fed regulations. Large department stores adopted card-based accounting systems, called Charga-Plate, that streamlined the links between their sales floors and credit departments. These systems solidified the connection between metallic identification cards and retail credit: the credit card was born.

Federal policymakers restrained consumer spending during wartime on the explicit promise that the postwar years would bring unprecedented abundance. Department stores were apostles of this future, and they entered the postwar era with a new credit product to draw in customers. Credit cards were a key feature of department store expansion in the 1940s and ’50s, out of city centres and into the growing suburbs.

The card allowed executives to wine and dine clients at restaurants and clubs

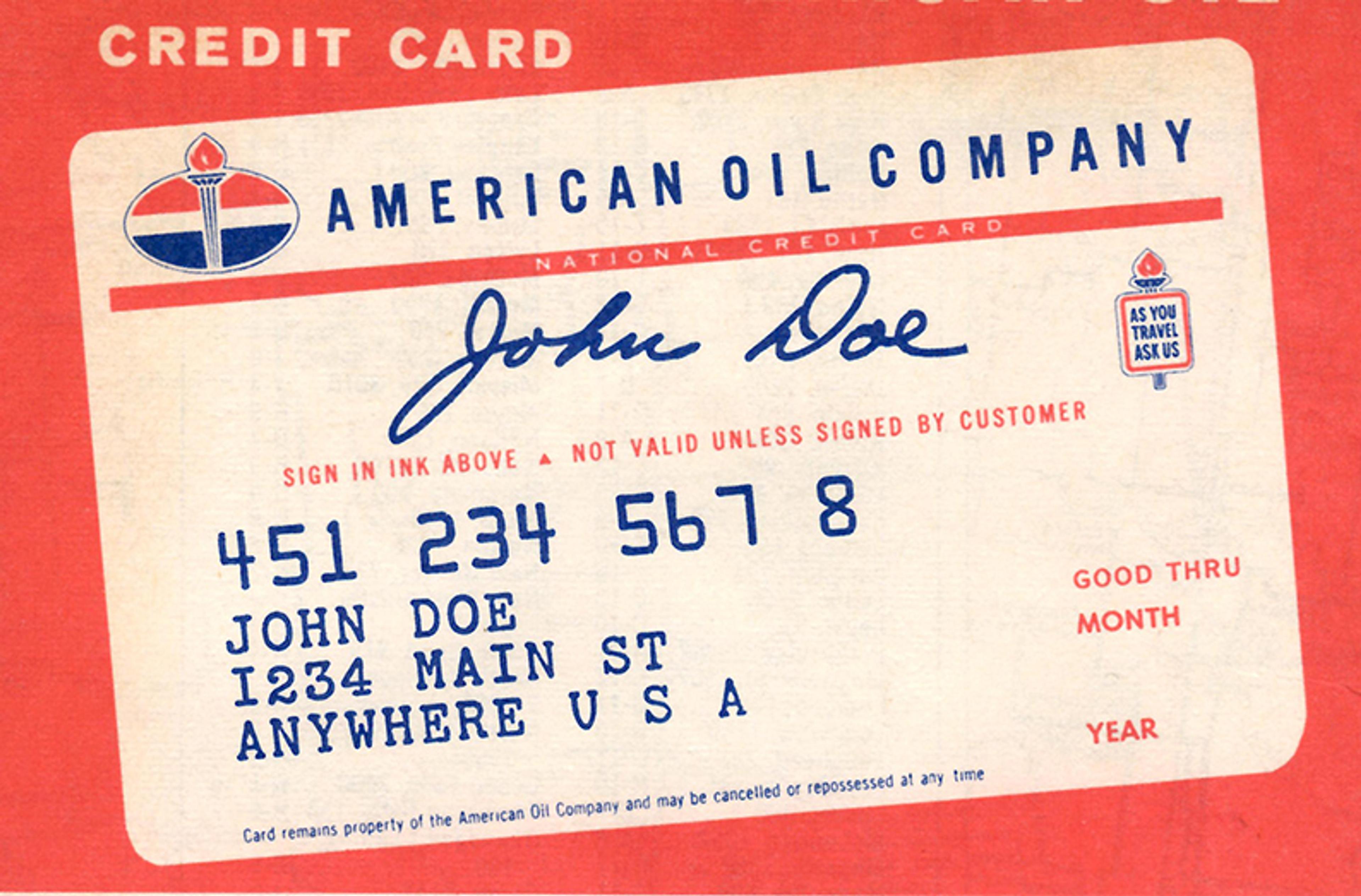

Other businesses also made credit cards central to their postwar plans. Gasoline companies, like Standard Oil of New Jersey, had developed nationwide charge account networks linking service stations in the years before the war. Wartime rationing halted credit sales. But in the late 1940s, service stations heavily promoted gasoline credit cards. Railroads, too, rolled out unified, card-based credit plans.

These travel cards set the stage for ‘universal’ travel-and-entertainment cards. Department store cards, offered by firms like Macy’s or Gimbels, were store specific. Gasoline and rail cards linked independent businesses within the travel industry under a unified credit plan. The watershed came in 1950, when Frank McNamara introduced the Diners Club card to executives in New York City. The name was self-explanatory. The card allowed executives to wine and dine clients at restaurants and clubs, first in New York and soon around the country. The plan quickly expanded to include the full suite of travel and entertainment services. The card was, in its own estimation, the ‘Indispensable New CONVENIENCE for the Executive – the Salesman – the man who gets around!’

Bankers came to universal cards by another road. In the 1950s, most US banks were small, local institutions. Financial regulations imposed during the New Deal bound banks in a web of rules that constrained their growth and profitability. Banks primarily served business customers, but many were eager to find new products and services to expand beyond the era’s tight regulatory limits.

The postwar growth of department store chains provided an opportunity. Department stores offered credit cards. Small retailers did not. In the early 1950s, a cohort of bankers in cities and towns across the country began experimenting with local card plans that linked small retailers into local credit networks. Although the plans were modest, bankers saw opportunity. Banks ‘should be the reservoirs for every type of credit in their communities,’ a Virginia banker observed in 1953, predicting that ‘banks may be handling the bulk, maybe all, charge account financing’ in the near future.

The scale of the bank credit-card market changed in the late 1950s when California’s Bank of America launched its BankAmericard plan. Unlike most US banks, the Bank of America was big. By 1958, it had more than 800 branches across the Golden State. Unlike most US banks, Bank of America also focused on consumer lending, financing the home mortgages and auto loans that made California suburban. To manage millions of consumer accounts, Bank of America invested in information processing technology. The bank was the first to adapt mainframe computers to banking in the 1950s, and executives believed that, with computers, a state-wide credit card could be possible – even profitable.

Bank of America’s executives recognised a fundamental challenge that confronted all universal credit-card plans: the bank needed to recruit enough merchant and consumer participants to make the card plan worthwhile to each group. Bankers had initially solved this problem by signing up merchants first, and then relying on merchants to solicit cardholders among their existing customers. Bank of America started from the other end. The bank had a large customer base. If it recruited cardholders first, executives reasoned, card-carrying consumers would draw merchants into the plan.

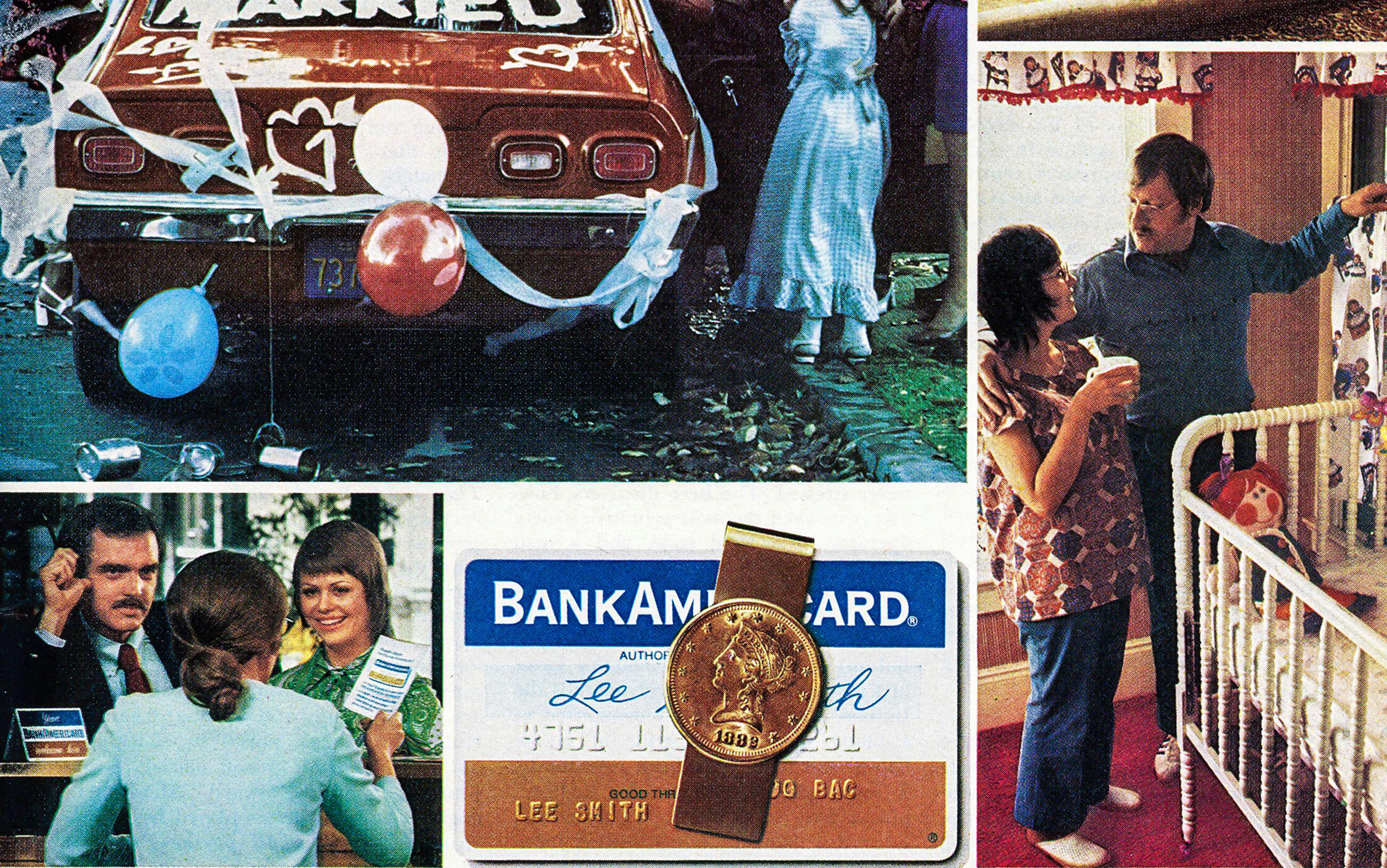

Beginning in Fresno in September 1958, Bank of America mailed unsolicited BankAmericards to its consumer accountholders, ultimately sending more than 2 million cards across California in the first few years. The cards came unexpectedly. They were also special: for the first time, the credit cards were not metal or cardboard, but embossed plastic, an innovation that added gee-wiz novelty to the bank’s card plan. The strategy proved expensive, reckless and effective. Bank of America gained a huge cardholder base, but at the cost of massive delinquencies and fraud losses.

By the early 1960s, department store and travel cards were well rooted in American wallets, but it was not yet clear that bank cards would succeed. Chase Manhattan, the nation’s second-largest bank, abandoned its credit card experiment after less than four years of trying in 1962. But other banks in the US were also struggling. Strict regulations ensured that, although banks were safe – very few banks failed in the postwar years – they were not very profitable. By the late 1960s, bankers increasingly saw credit cards, which combined innovative information technology with access to affluent consumer markets, as the road to the future – as the key to innovating around the restrictive financial rules.

The route to this future, however, was not initially obvious. Early on, credit card executives obsessed over scale. Card systems had high fixed costs, so that the more transactions a card plan processed, the lower the cost of each transaction. Yet the quest for scale ran first into the market’s fundamental division by gender. Travel and entertainment cards, like Diners Club and American Express – the latter of which began issuing cards in 1958 – catered to male business executives. Department store and bank cards, by contrast, focused on female-led family shopping. The BankAmericard was the ‘family credit card!’

In the early 1960s, Bank of America set out to merge rather than segment. The bank enrolled hotels and airlines, expanding its market from suburban housewives to their husbands. In these ambitions, Bank of America faced the second impediment to scale: geography. Under existing banking laws, it could not build branches outside of California. Its travel card competitors offered cards from coast to coast. ‘We do not believe that the Bank of America is a competitor of the Diners Club,’ boasted Alfred Bloomingdale, the Diners Club chairman, in October 1966.

In their haste to get cards into consumer hands, most banks failed to perform thorough credit checks

Bloomingdale was correct, but the tide was turning against him. As he wrote, Bank of America executives were building a credit card network that would link the plans of local banks into a nationwide system. To overcome the regulatory barriers that confined banks within individual states, Bank of America executives recruited large banks across the country, using their local merchant and consumer relationships in their states to create a national bank card plan.

The California bank also lit a fuse. BankAmericard was exclusive: only banks chosen by Bank of America could join. Competing firms responded by forming their own card networks. At first, these were regional – the Midwest Bank Card System centred on Chicago, while the New England Bankcard Association centred on Boston. Quickly, these regional consortia coalesced into a competing national network – Master Charge (later renamed MasterCard).

It is difficult to overstate the frantic growth of bank card plans in the late 1960s. Fewer than 70 banks issued cards in 1965. More than 1,200 did by 1970. Consumers experienced this growth as a steady hail of plastic. Bank of America encouraged licensees to adopt unsolicited mailing. As the banker Dee Hock recalled in his memoir, the strategy ‘all boiled down to “mass issue hundreds of thousands of unsolicited cards, sign every merchant in sight, and all will come right in the end.”’ Competing banks adopted the strategy as well. Not to be outdone, department stores and gasoline companies also mass-mailed cards. Tens of millions of unsolicited cards flooded consumer mailboxes from the start of the boom in 1966 until US Congress banned unsolicited card mailing in May 1970.

Banks careened into the credit card market to recruit new customers, meaning that, while many used their existing accountholder lists as the starting point for mass solicitation campaigns, banks invariably bought catalogues of potential cardholders from credit bureaus, mass mailing firms and other sources. David M Kennedy, chairman of Continental Illinois Bank in Chicago in the 1960s, explained that his bank mailed cards to ‘customers and shareholders and a few others in whom there was reason to place confidence [emphasis added].’ His vagueness was suggestive. Later investigations revealed that, in their haste to get cards into consumer hands, most banks failed to perform anything like thorough credit checks. Beating competitors to the mailbox was the overriding concern.

To call these campaigns reckless fails to do them justice. Unsolicited mailing delivered plastic credit that was live and ready to use. There were no systems for activating credit cards. Recipients – intended or unintended, legitimate or fraudulent – needed only open the envelope, sign the card, and use it.

The cascade of unsolicited credit drew the attention of consumer groups, labour unions and policymakers at all levels of government. Bankers pursued cards to innovate around New Deal regulatory restrictions and to build consumer lending markets from scratch. Many did so to expand beyond downtowns that were becoming Blacker and poorer, and to reach affluent, white suburbs. In doing so, bankers inadvertently sparked a political backlash that would drastically hem in their ambitions.

The first thrust came in the form of price controls, which reflected consumers’ desire for fair credit prices and protection from excessive debt. At the time, state laws regulated the interest rates lenders could charge on most consumer lending. Credit cards were expensive and initially fell under an exemption that allowed banks and other card issuers to charge whatever rates they saw fit. As cards rained down, organisations like the American Federation of Labor and Congress Industrial Organizations and the Consumer Federation of America led state-level campaigns to bring credit card lending under state interest-rate rules. By the early 1970s, most states restricted card rates to between 12 and 18 per cent.

These restrictions, in turn, discouraged banks and other lenders from putting consumers into long-term debt. Banks borrowed the money that they ultimately lent consumers. Price controls forced banks to hold the risk that if their borrowing costs went up – for example, because the Fed raised rates to fight inflation – they would not be able to pass higher costs on to borrowers. Price controls encouraged bankers to keep repayment periods short, making cards tools for convenient credit, not long-term debt.

Mass credit card mailing sparked a full-scale moral panic and a massive policy response

As consumer and labour groups organised to control the price of credit, they also sought protection from the multiplying risks that appeared with the deluge of cards. Consumers feared identity theft and potential liability if their cards were lost or stolen (especially cards they had never requested and never seen). The cascade of cards alerted consumers to the new power of national credit bureaus and to the infuriating problems of correcting billing errors generated through automated accounting systems. Some even feared for the moral integrity of the household, as banks mailed cards to wives, children and a few deceased relatives.

Mass mailing sparked, in short, a full-scale moral panic and a massive policy response. Congress enacted a wave of consumer legislation in the late 1960s and early ’70s, including the Truth-in-Lending Act, the Fair Credit Reporting Act, and the Fair Credit Billing Act, all meant to make consumer credit markets safer. By 1976, Fed analysts reflected that ‘credit cards have been the principal subject of by far the majority of the consumer credit legislation proposed and/or enacted since 1970.’

Bankers leapt into the credit card market in the late 1960s to escape the tight regulations that constrained their industry. The consumer backlash and the wave of legislation that followed fundamentally constrained credit card plans. Instead of a source of profits, cards became another source of low-margin lending. What had once seemed like the road to the future appeared as just another dead end.

The political emphasis on credit cards as a consumer protection issue missed their importance as a bank regulatory problem. After the Great Depression, US Congress tried to keep banks small and geographic restrictions were a cornerstone of this policy. Bankers built card networks to overcome these restrictions, but in the 1960s they still thought of cards as local products. Banks signed up merchants and consumers in their geographic territories. Because cards did not generate large profits on their own, bankers expected cards to create relationships with merchants and consumers who would then use other banking services. Consumers could use their BankAmericards and Master Charge cards across the country, but they mostly used them close to home.

The card networks, though, also opened vectors to the gradual breakdown of geographic restrictions and with them the state-level protections consumers had so recently won. The process was gradual and largely unanticipated. In some parts of the country, bank card plans began to cross state lines. In the Midwest, for example, large urban banks – like the First National Bank of Omaha, in Nebraska – partnered with small community banks in neighbouring states – like the Coralville Bank and Trust, in Iowa. The Coralville Bank suggested potential cardholders and signed up local merchants, while First of Omaha issued BankAmericards to the Coralville Bank’s customers and managed their credit accounts.

These arrangements raised difficult legal questions about where card plans were regulated – in Iowa where consumers lived and used their cards, or in Nebraska where the bank was located? Over time, federal courts and eventually the US Supreme Court determined that cards would be regulated by the state where the bank was located. At first, the cases attracted little attention – nearly all states regulated credit card rates, and the difference between 12 and 15 per cent interest was significant but small. Soon, though, the stakes would change.

At the same time that legal questions about regulatory place and space worked through the Midwestern courts, large banks in cities like New York and Chicago began to look for new ways to innovate around geographic regulations and other restrictive policies. State consumer regulations enforced a limited view of cards as strictly a credit device. Bankers, like Walter Wriston, chairman of New York’s Citibank, came to see cards as something else: banks in miniature. Citibank was a giant, global bank. It operated more than 200 branches abroad, but it could not build branches outside New York State. Paired with other technologies, like point-of-sale terminals and ATMs, Citibank executives and their peers increasingly saw cards as a way to break the territorial restrictions on consumer banking.

At the peak in 1979, banks approved nearly 75,000 credit card applications a day

In August 1977, Citibank made its move. The year before, BankAmericard announced plans to rebrand itself as Visa, distancing the card from Bank of America and signalling the globe-spanning ambitions of the network. By this time, Citibank executives believed that consumers saw only the card network – Visa and Master Charge – rather than the local banks that issued cards and managed consumer accounts. Timed with Visa’s rebranding, Citibank launched a nationwide card-solicitation campaign, mailing reams of pre-approved applications to consumers across the country. Consumers, many assuming the offer was part of the Visa changeover, accepted Citi cards by the millions.

Citibank’s card blitz took its competitors by surprise. Bankers still believed that local ties were essential to making card plans profitable and ensuring that borrowers repaid their debts. But bankers also knew not to be complacent. Just like in the 1960s, Citi’s competitors responded in kind, sparking a renewed cycle of mass solicitation. At the peak in 1979, banks approved nearly 75,000 credit card applications a day, ultimately surpassing department stores as the leading source of credit card borrowing.

Citibank’s timing initially proved ill-chosen. In the late 1970s, policymakers in the Jimmy Carter administration and at the Federal Reserve struggled to deal with persistent, unyielding inflation. Prices ratcheted up 6.5 per cent in 1977, then 7.5 per cent in 1978, before jumping over 11 per cent in 1979. The causes of inflation were heavily debated, and some blamed consumer credit generally – and credit cards specifically. Consumers used credit to engage in ‘anticipatory buying’, seeking to buy ahead of price increases and thereby creating more demand and driving prices higher.

Beginning in October 1979, Paul Volcker, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, began a dramatic campaign to kill inflation. The Fed determined to limit the growth of the money supply, allowing interest rates to rise as high as necessary to constrain monetary growth. Because lenders like banks and department stores borrowed the money they lent consumers through cards, and because state interest rate restrictions limited the prices card lenders could charge consumers, surging interest rates punished card issuers. By March 1980, one Fed governor observed that ‘there is also a good deal of concern regarding losses on consumer credit cards, but that’s news to no one.’

What was a problem for the industry was a crisis for Citibank. As Volcker ratcheted up rates, Citi’s cost of funds exceeded what it could charge cardholders. New York’s consumer protection laws were strict. Despite Citi’s pleading, policymakers would not budge. The bank, which already had more than 2 million MasterCard customers in and around New York before Citibank’s Visa campaign, now had 4 million customers across the country. Citi had staked its future on its card business; Fed policy threatened to destroy it.

The usual explanation is that consumers are irrational, a polite way to say they’re always getting tricked

Desperate, Citibank’s lawyers searched for a loophole. They found one in an obscure law called the Bank Holding Company Act, which allowed them to relocate their card operation to another state – one without New York’s strict rules – but only if the state’s legislature invited them to do so. Citi executives promised hundreds of financial services jobs, an offer South Dakota accepted in March 1980. South Dakota had no applicable price restrictions, and Citibank exported its high rates to cardholders across the country.

State-level price controls had fundamentally restrained credit card plans, forcing card issuers to internalise interest-rate risk and discouraging them from keeping borrowers in long-term debt. South Dakota, though, traded regulatory benefits for jobs and tax revenues. Other states quickly followed. In 1981, Delaware copied South Dakota’s legislation verbatim, luring banks like Chase Manhattan. As Volcker’s Fed eased rates in the early 1980s, banks launched card promotions from their new homes, offering not only high interest rates but also new annual fees.

Some states tried to hold out. For a time, Massachusetts maintained its 18 per cent rate limit and did not allow annual cardholder fees. Beginning in 1983, out-of-state banks flooded the state with card offers. Expensive credit pushed out inexpensive credit. Massachusetts’s banks lost patience. They threatened to relocate if the state legislature did not raise rates, a concession they won in early 1985.

At first glance, the Massachusetts story is counterintuitive. If consumers prefer lower prices, wouldn’t they just choose the lowest-cost cards? Yet as the Massachusetts bankers recognised, card issuers in high-interest states could afford heavy marketing costs, pushing out low-cost alternatives. Comparison shopping is not costless. For consumers, it was easier to take the offer in the mailbox. For banks, it was cheaper to fight for deregulation than to fight for market share. Bad plastic money crowded out good.

In the years since, bank credit card plans have been consistently more profitable than other forms of bank lending. In theory, competition should bring down these profits, but it doesn’t. The traditional explanation is that consumers are irrational, which is a polite way to say they are always getting tricked. Over time, banks and other card issuers found new ways to manipulate consumers: affinity cards to create emotional and social connections (I got my first card from my university’s alumni association); low minimum payments to drag out debt; teaser rates to encourage consumers to shift debts from one bank to another; high fees for the slightest contractual infraction.

The largest card-issuers are the worst offenders. Consolidation—like the recently proposed Capital One and Discover merger—further restrains competition and ensures that the practices of the most exploitative firms become industry norms.

Part of the story, too, is that the US political economy has continued to rely on household borrowing, even as the high-paying jobs that enabled Americans to repay their debts have disappeared for many. Indeed, the great benefit – if it can be called that – of unregulated credit is that banks are willing to offer cards to consumers deemed less creditworthy: often poor and minority borrowers who had been excluded from mainstream finance. Such borrowers, often with precarious incomes, are that much more likely to get stuck in a high-interest debt trap, always revolving, never repaying.

All the while, aggregate credit card debt continued on a relentless upward ratchet. Outstanding card debt doubled from 1980 to 1985, doubled again by 1990, again by 1995, and again by 2005, topping out in April 2008 at more than $1 trillion. The crisis of 2008 brought a brief reckoning. By 2011, debt growth resumed until the COVID-19 pandemic, broke when the economy broke, and has since spiked up, reaching new all-time highs month after month.

The obvious question is: what to do? A federal interest rate cap would be a good start, as would strict limits on cardholder fees. US Congress could (and should) eliminate reward plans that make cards engines of upward redistribution, from struggling borrowers to affluent point-collectors. These would be dramatic changes and would still not get close to the root of the problem. In the United States, mass consumption came into being paired with mass credit. Critics recognised then the dangers of this combination, the need for larger and larger doses of the credit stimulant to prevent an economic relapse. Absent some fundamental restructuring, there is little to do but keep the plastic juice flowing.

Plastic Capitalism: Banks, Credit Cards, and the End of Financial Control is the forthcoming book by Sean H Vanatta, publishing in July 2024 via Yale University Press.