In 1812, the English novelist Frances Burney described her mounting terror as she prepared to undergo a mastectomy without any anaesthetic. Having two hours to wait until the dreaded event (her ‘execution’, as she put it), she wandered into the room where the operation was going to take place and ‘recoiled’. In an effort to control her fear she ‘walked backwards & forwards till I quieted all emotion, & became, by degrees, nearly stupid – torpid, without sentiment or consciousness’.

When seven men arrived, all dressed in black, and began laying down two ‘old mattresses’, covering them with an ‘old sheet’, Burney ‘began to tremble violently, more with distaste & horrour of the preparations even than of the pain’. When told to mount the bed, she stood ‘suspended, for a moment, [contemplating] whether I should not abruptly escape – I looked at the door, the windows – I felt desperate’.

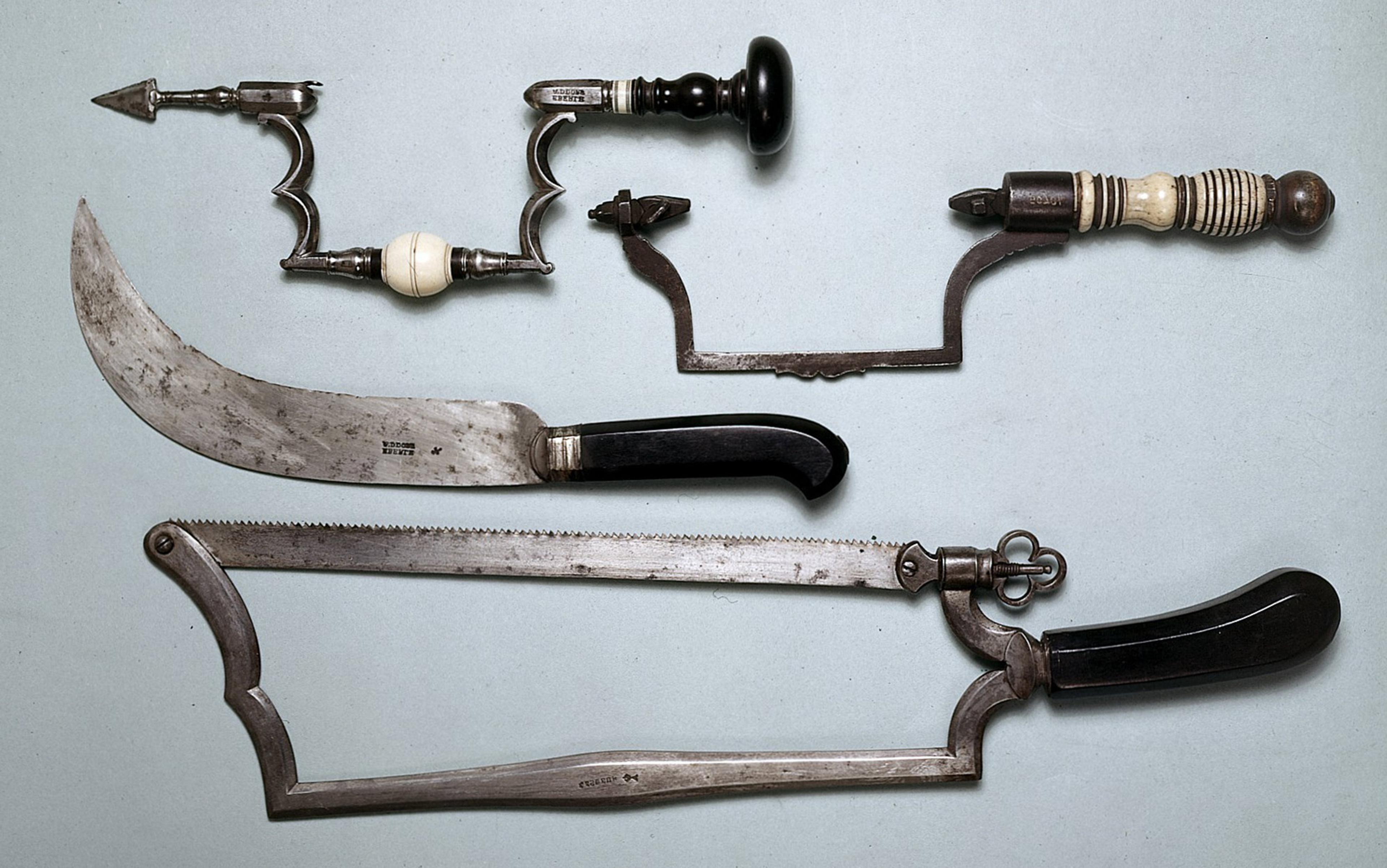

Submission, however, was necessary. The surgeon spread a cambric handkerchief over her face and took up the knife. Burney was consumed by a ‘terror that surpasses all description’. When ‘the dreadful steel was plunged into the breast – cutting through veins – arteries – flesh – nerves’, she wrote: ‘I needed no injunctions not to restrain my cries. I began a scream that lasted unintermittingly during the whole time of the incident – & I almost marvel that it rings not in my Ears still! so excruciating was the agony.’

Burney underwent surgery more than three decades before the first use of modern anaesthetics as part of human medicine. When she sat down to record her experiences there was a rich language of suffering she could draw upon. It was widely believed that this language of pain held clues to the original causes of distress that were embedded within its metaphors. Medical textbooks encouraged physicians to elicit complex accounts of pain from their patients. In 1730, for instance, the influential physician Bernard Mandeville recalled a patient asking his doctor whether he was tired of hearing ‘so tedious a Tale’ of pain. His physician gently murmured: ‘Your Story is so diverting that I take abundance of delight in it, and your Ingenious way of telling it, gives me a greater insight into your Distemper, than you imagine.’

A century later, physicians took a very different view of pain narratives. Writing in the 1860s, Peter Mere Latham (physician extraordinary to Queen Victoria) inverted Mandeville’s comment, grumbling that ‘every person’s complaint is interesting to himself, he is apt to discourse about it rather too much at large, and too little to edification’. Latham lamented that ‘among the upper classes of life, we are obliged to listen to the patients’ tale’ – presumably because their social status entitled them to opine – but he confessed that ‘we generally cut [their accounts of pain] as short as possible, in order to get to our plan of investigation’.

With the invention of chloroform in the 1840s, doctors celebrated the fact that the ‘groans and shrieks of sufferers beneath the surgeons’ knives and saws, were all hushed’. So said the surgeon-dentist Walter Blundell. According to Blundell, writing in 1854, surgeons were now able to carry out their work ‘as on breathless, lifeless forms’. Anaesthetics rendered patients passive, unconscious bodies, stripped of sensibility, agency and, critically, words.

This shift from encouraging the active, even verbose, person-in-pain to cherishing the silenced is evident even within different editions of a single textbook. For example, in early editions of William Coulson’s popular clinical text On the Diseases of the Bladder and Prostate Gland (first published in 1838 and going through a number of editions until 1865), readers are told that a man with kidney stones would suffer intensely. The

jolting of a carriage is insupportable to him…. As the evil increased, micturition becomes more and more frequent and distressing; the pain following the act is very severe, – patients writhe with their bodies, and grind their teeth in agony.

Compare this with the same passage from the 1881 edition of his book:

The jolting of a carriage increases his symptoms…. As the stone increases in size, micturition becomes more frequent and distressing, and the pain or uneasiness at the end of the penis becomes more constant and severe.

The earlier focus was on the ‘evil’ of suffering. Now there’s a more detached description of ‘symptoms’ and the suffering itself has been downgraded to ‘pain or uneasiness’. Patients no longer ‘writhe with their bodies, and grind their teeth in agony’, but simply hurt more.

The emotional and aesthetic ‘thinning’ of clinical languages has continued ever since, moving the subjective experience of pain further towards the periphery of medical discourse. The introduction of Visual Analog Scales (a line with ‘no pain’ and ‘the worst pain imaginable’ at either pole) denies the importance of detailed narratives entirely. Meanwhile, Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (or fMRI) promises to eradicate the subjective person-in-pain altogether: she is not required to speak, nor even to point. Pain is little more than ‘an altered brain state’. The complex pain narratives of earlier periods have been decisively dismissed.

Pain is a ‘monster’, an ‘intruder’, a knife that cuts, a dog that bites, a fire that burns

Or have they? Perhaps the ‘thinning’ of pain narratives is simply a clinical conceit that ignores the way actual patients communicate their pain. In other words, physicians might no longer be listening, but people-in-pain have continued talking. What is especially intriguing is that the metaphors and analogies they’ve used to describe what they are feeling have changed over time.

In all periods, pain is described as an independent entity. It is a ‘sulky visitor’, a ‘monster’, an ‘intruder’, as well as a knife that cuts, a dog that bites, a fire that burns. But the rich religious language of pain, common in past centuries has largely disappeared. For Christians in the 19th century and earlier, the Bible provided extravagant narratives of suffering, from Job to Jonah, from the Psalms to Jeremiah. Above all, Christians could turn to the sufferings of Christ to speak their agony. They need only ‘Clasp the Rood Divine Of Him Whose Blood-sweat dyed Gethsemane!’ and plead, ‘Forgive me, Lord, who caused Thee agony… hear my anguish’d prayer – “O Crucified, thy will, not mine, be done”.’

Today, arrows of pain are not seen to be flung by an infuriated deity but are blindly caused by a penetrating germ or virus. When the pharmaceutical ability to eradicate chronic pain was limited, endurance could be valorised as a virtue: but with effective pain relief passive endurance became perverse. Bodily agony is no longer conceived of as ‘a warning angel’, and therefore as something that should be used as a mechanism either for spiritual renewal, or to be passively endured in imitation of the Calvary. Rather, pain is an ‘enemy’ to be fought and defeated, and it is the duty of patients and physicians to tackle it with all guns blazing. Hence the prevalence of military metaphors in contemporary pain narratives and ‘sickness memoirs’ such as A Private Battle (1979) by Cornelius and Kathryn Morgan Ryan, or Winning the Chemo Battle (1988) by Joyce Slayton Mitchell.

Secular belief systems also dealt a fatal blow to the notion of an afterlife – and therefore the idea that the pain suffered in this life can be somehow set against any suffering in the next one. As a consequence, pain has become the ultimate assault on an individual’s identity. It is common to hear chronic pain patients describe pain as an ‘an enemy… unbelievable… without reason… why should this happen to me’, or as something that ‘has to be taken away… must be tackled’. Because there is no ‘self’ that survives the death of the body, any attack on the individual in the here-and-now is particularly distressing.

Patients themselves are no less eloquent about their pain, despite this new secular approach to it. To take some examples from the medical, legal and academic literature of the past few decades, one paraplegic explained that he felt as if ‘a family of snakes’ was ‘squirming’ in his buttocks. Another patient described pain as ‘like a demand from Her Majesty’s Inspector of Taxes’. A woman who experienced phantom limb pain after her arm was amputated observed that it felt like ‘champagne bubbles and blisters’. A man with chronic back pain said; ‘my back hurt so bad I felt like I had a large grapefruit down about the curve of the back’. Even more creative was the woman who said her headache felt ‘like a bowl of Screaming Yellow Zonkers popping hard behind my forehead’.

Young children also possess a richly figurative language of pain. They might describe their pain as ‘a war in my stomach’, ‘lots of banging’, ‘mean’, ‘snow’, ‘ouch’, ‘sounds funny’, ‘cymbals clapping’, ‘grody to the max’, and ‘like mosquitoes poking around’. Or, as one six-year-old child eloquently put it: ‘Whenever my ears start to pain, I lose my smile and feel bad.’ Witnesses to such stories of pain instinctively grasp their meaning.

The chief difference between Burney’s time and ours is that patients’ metaphors are often ignored rather than elicited by the medical fraternity. This has not silenced patients. Like people-in-pain in past centuries, they want to know what has ‘gone wrong’, and to make sense of the disconnect between ‘me’ and ‘my pain’, and communicate their experiences to others.

This inherently social nature of pain provides a clue as to why talking about pain is so important – indeed, necessary – in human societies. It is why Burney wanted her sister Esther to hear about her mastectomy from her own pen, rather than second-hand. She recognised that ‘from the moment you know any evil has befallen me your kind heart will be constantly anxious to learn its extent, & its circumstances as well as its termination’. For Burney, sharing the story of suffering would draw loved ones, such as her sister, closer.

pain exposes our fragile connection to other people and serves as a reminder of our need for those around us

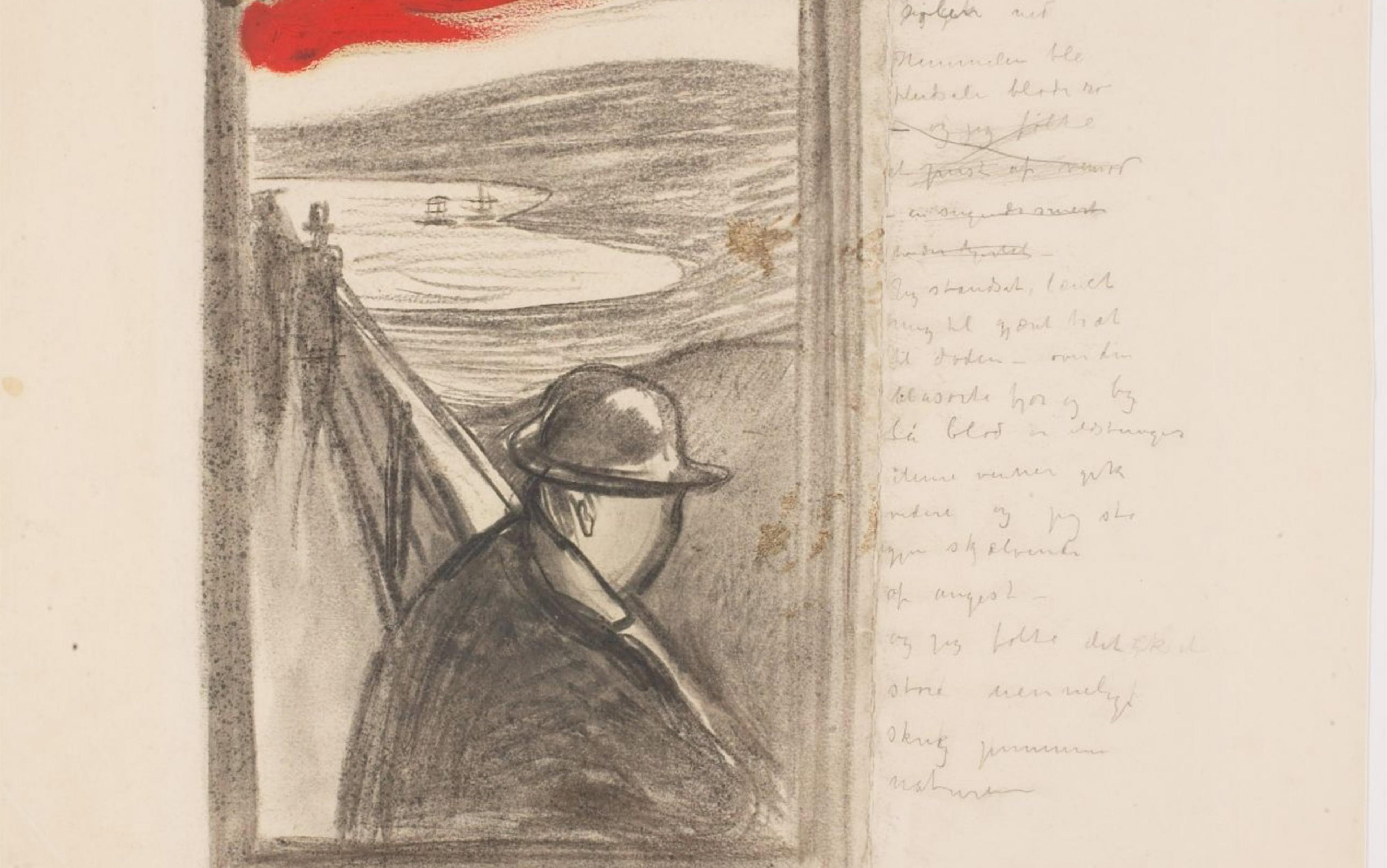

Talking about pain is a way of cementing interpersonal bonds: when people ‘suffer with’ their loved ones, they are bearing testimony to their closeness to that person. Witnesses to pain often find the experience agonising themselves, which can lead them to further intimacy with sufferers. This is what Claire Tisdall alluded to in her memoir based on the First World War. Tisdall, a nurse, admitted she’d been ‘burning with the agony of losing a dearly loved brother at Ypres’ and so her ‘feelings towards them [Germans] were less than Christian’. Nevertheless, one day she was given the job of looking after some German prisoners on their way to the hospital. One ‘very young, ashen-faced boy’ with a leg-wound looked up at her and murmured ‘Pain, pain’, an episode about which Tisdall wrote: ‘a bit of the cold ice of hatred in my heart… softened and melted when that white-faced German boy looked up at me and said his one English word – “Pain”.’

More than half a century earlier, the physician Samuel Henry Dickson in his Essays on Life, Sleep, Pain, Etc (1852) put the case more strongly: ‘Without suffering there could be no sympathies,’ he concluded, ‘and all the finer and more sacred of human ties would cease to exist.’ At the very least, pain exposes our fragile connection to other people and serves as a reminder of our need for those around us.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, these communities of fellow-sufferers have been bolstered by the internet. Feeling belittled or ignored by their physicians (who, to be fair, face immense pressure to ‘process’ patients ‘efficiently’), people-in-pain have turned to social media and online communities. These sites offer sufferers a language with which to frame their pain; they enable them to communicate this pain to others; and they provide sufferers with a community in which they feel that their experiences are validated. ‘Bodying forth’ (a term coined by the Swiss psychotherapist Medard Boss in the 1970s) into cyberspace enables pained bodies to fling themselves out of the constraints of geography, medical power regimes and social stigmatisation.

As Frances Burney discovered in the early 19th century, writing about her agonising experience allowed her to defy conventions that required surgical patients to endure their torments stoically and that women in particular remain silent about breast cancer. She was proud of the fact that when her surgeon asked: ‘Qui me tiendra se sein?’ (‘Who will hold this breast for me?’), she’d replied: ‘C’est moi, monsieur!’ In recording her experiences and encouraging her sister and friends to circulate her story, she could reclaim social agency and also excise her memory of suffering.

Against the isolating effects of suffering, Burney’s narrative of pain enabled her to create communities of sympathy. And in this, mercifully, there is continuity. For, today as then, the creative ways in which people-in-pain frame their experiences provide important clues to the unspoken meanings they attach to their suffering, and offer critical guidance to those around them about how they might reach out to help.