In Human, All Too Human (1878), Friedrich Nietzsche wrote that ‘A lack of historical sense is the original failing of all philosophers.’ In accusing philosophy of lacking historical sense, Nietzsche was echoing broader trends in 19th-century thought. In comparison with the ‘philosophical’ 18th century, the 19th century is sometimes described as the ‘historical’ century, one in which investigation into more universal features of human reason gave way to increased focus on how particular historical trajectories influence language, culture and moral assumptions.

The 19th century is also what one might call the ‘philological century’. Philology is the critical study of written sources, including their linguistic features, history of reception and cultural context. Today, the term sounds outmoded, evoking dusty, learned tomes of fastidious source criticism. However, philology was a leading intellectual discipline in 19th-century Germany due to a flurry of methodological developments that revolutionised our understanding of ancient and sacred texts. New rigorous techniques of verifying sources were developed, merely speculative hypotheses were discouraged, more detailed comparative studies of language were conducted. While such methods were scholarly, sometimes bordering on scholastic, their application had significant cultural impact, spilling out of scholarly journals into broader public consciousness.

Nietzsche imbibed these trends as a young man. An all-round talented student (mathematics was a notable exception), he gained admittance as a 14-year-old to Schulpforta, one of the most prestigious humanistic schools in Germany. A training ground for scholars and teachers, the school’s specialty was classical antiquity, and Nietzsche received a rigorous education in Greek and Latin, read historical works by Voltaire and Cicero, and wrote philological treatises on topics such as the saga of Ermanarich and the Greek poet Theognis.

This philological education informed not only his early works that deal directly with Greek antiquity, such as The Birth of Tragedy (1872), but also his later books on morality and moral psychology. Appreciating this philological influence is crucial for understanding the significance of his philosophically most important work, On the Genealogy of Morality (1887), and the ‘genealogical’ method of philosophy it has inspired.

On the Genealogy of Morality is a puzzling book. It deals with many classic topics of moral philosophy, such as the concept of good, free will, moral responsibility and guilt. However, it does not investigate them in a typical philosophical fashion – for instance, by asking ‘What is good?’ or ‘Do we have free will?’ Rather, it takes a historical approach, asking where our ideas about the good, or free will, or guilt, have come from.

Nietzsche’s answers to these historical questions were and continue to be, to put it mildly, controversial. Not for nothing did he describe himself as ‘dynamite’. For instance, he argued that contemporary Western egalitarian and altruistic assumptions were a form of ‘slave morality’ that emerged from the frustrations and ressentiment (roughly, resentment) of a priestly caste. This slave morality was a reaction against what Nietzsche calls ‘master morality’, an archaic ethics that emphasises virtues of excellence, health and respect for social hierarchy. Master morality valorises strength and denigrates the meekness and bookish intellectualism of the religious leaders of the priestly caste. In response, according to Nietzsche, the religious leaders invented a new evaluative framework in which they come out on top – one in which aggressiveness is classified as ‘evil’ and meekness and altruism as ‘good’ – a revaluation of existing values. These moral assumptions are then taken up by the lower slave caste, as they valorised their lowly status and enabled them to reinterpret their impotence as principled choice. In sum, on Nietzsche’s view, many of our fundamental moral assumptions derive from archaic status competition.

What has puzzled many readers of Nietzsche’s genealogy is how these historical claims are supposed to be relevant to philosophical questions about morality. Nietzsche states that his ultimate aim is to assess ‘the value of our values’, but it is not clear how his historical claims could or should contribute to this assessment. In turning to history, it might seem that Nietzsche is simply shifting the subject of moral philosophy, following the adage that if you don’t like what is being said, then you should change the conversation. After all, the question of where our values come from just seems like a different question from philosophical questions about their nature, value and authority. If Nietzsche is trying to use this history to answer these philosophical questions, then it might seem he is committing a fallacy, the ‘genetic fallacy’.

Showing that something has a bad origin isn’t sufficient to show that it is bad

The genetic fallacy is the purported mistake of evaluating something on the basis of its origin or past characteristics. For instance, imagine a friend tells you that you should not wear a wedding ring because wedding rings originally symbolised ankle chains worn by women to prevent them from running away from their husbands (the example is from Attacking Faulty Reasoning (7th ed, 2012) by T Edward Damer). Even if wedding rings have such a dubious history, this history does not show that it is bad or objectionable to wear them now. When Nietzsche suggests that he should reevaluate Christian morality on the basis of this origin story, we might suspect he is employing a similar type of fallacious reasoning.

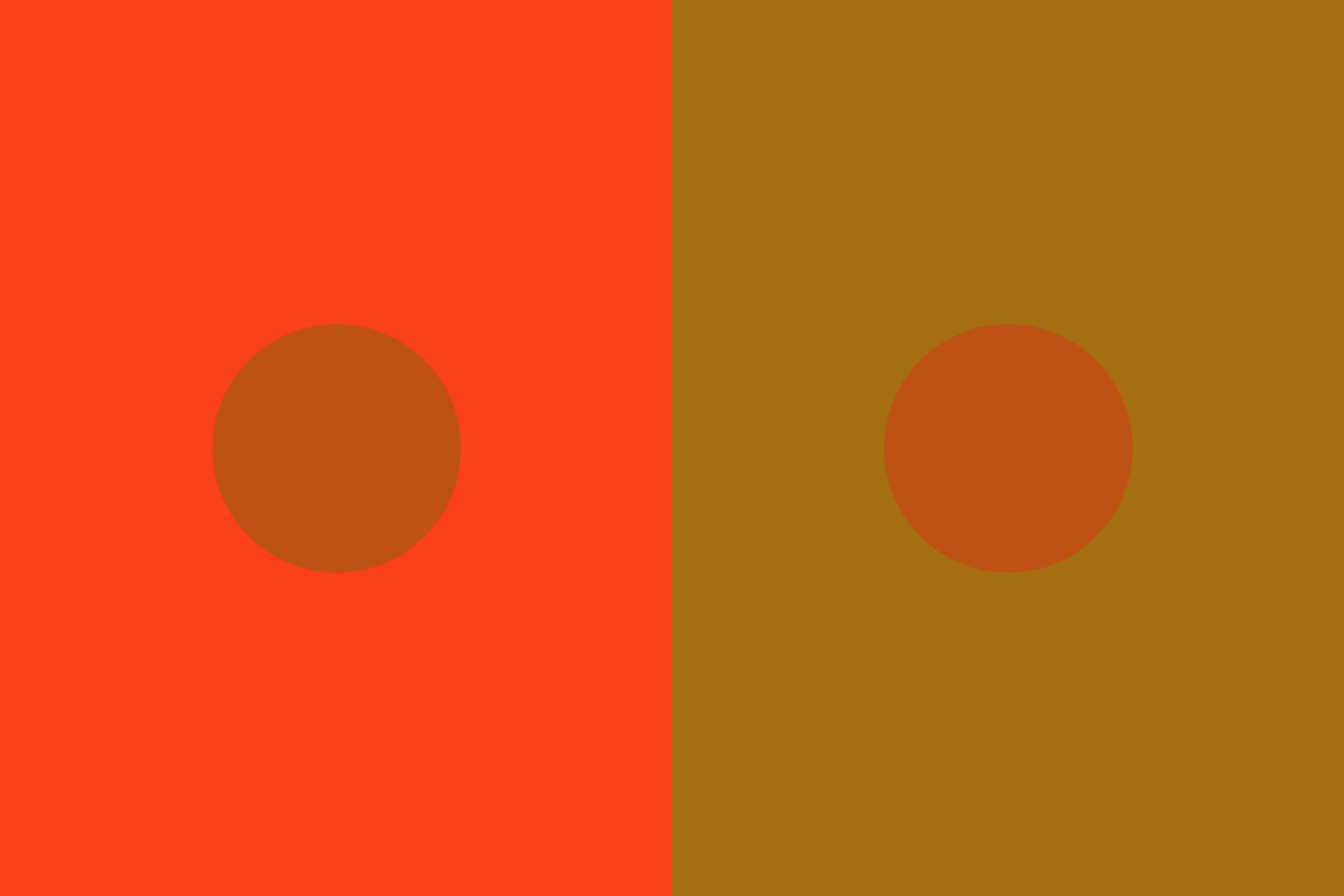

Concerns about falling prey to the genetic fallacy are part of what explain moral philosophy’s lack of a historical sense. Showing that something has a bad origin isn’t sufficient to show that it is bad, as the previous examples indicate. Neither does examining the origins of our values seem necessary for evaluating them. To evaluate our moral beliefs and practices, it seems that we need only look at the reasons for and against them, not the causes of our beliefs in them. For instance, to criticise egalitarianism, we should consider potential objections to egalitarian attitudes, such as that they recommend levelling down, prevent the achievement of human excellence, or fail to honour supposed differences in moral desert. Whatever one thinks of these criticisms, it seems that making and assessing them does not require looking at the history of our values. If these points are correct, we can see why moral philosophy would proceed ahistorically: if moral philosophy aims to critically scrutinise the value of our values, and origin stories are neither necessary nor sufficient for this purpose, then origin stories are irrelevant to moral philosophy.

Nietzsche thought this reasoning mistaken, although exactly why he thought so is a matter of scholarly dispute. His historical critique is typically understood in one of two ways: either he held that historical information was directly relevant to the authority or justification of moral norms, or he held it was indirectly relevant by providing evidence that moral attitudes are motivated by ressentiment and/or hinder great human achievements.

To grasp how history might be directly relevant to the status of our values, we might begin by acknowledging that the value of many human artefacts depends on their history – Picasso paintings are more valuable than perfect replicas because they come from Picasso and not from a copyist, and your family heirlooms hold special value because of their historical connection to your family. Something similar may be true of our values.

For instance, if our values include or imply commands, then their history might be relevant to their authority, our obligation to obey them. Many commands depend for their authority on the authority of the commander, and vengeful clergy with status anxiety do not seem like authoritative commanders. More specifically, one might think that the authority of moral commands depends on their coming from God or pure reason, so insofar as historical investigation reveals that they derive from a secular ‘human, all too human’ source, then history might undermine their authority. If Christian values turn out to have been born from resentment, then that, on this sort of argument, undermines their value to us today. In a similar way, philological work that traces the Bible back to secular origins might undermine the authority of the moral teachings contained within it by undermining the claim that those teachings come from God or Jesus.

Another way that the status of our values may depend directly on their history is if they include or imply beliefs about value claims, as historical information can affect whether our beliefs are justified. I might destabilise a belief by coming to know that the process by which I acquired that belief is unreliable. For instance, say I believe a rumour that my grandfather used to pilfer money from the church collection jar, and I acquired this belief from my father. However, I then learn that my father heard this rumour from his brother, who is a notorious liar and resentful of his strict religious upbringing. Given that my belief traces back to an unreliable source, I might reasonably think that my belief is no longer justified.

If moral norms were originally motivated by ressentiment, then this directly ‘taints’ them in some fashion

Similarly, it might be that we acquired our moral beliefs from our parents (and broader culture), who acquired them from their parents (and broader culture), all the way back to the vengeful clergy. But if vengeful clergy are not a reliable guide to the moral truth, then I should distrust my parents’ teachings and therefore my moral beliefs. Nietzsche’s historical story might therefore help emancipate us from illusions by exposing information that challenges our faith in cherished but unjustified assumptions.

These points about authority and justification are points that philosophers sometimes make about the relevance of history for moral philosophy, and it is possible that Nietzsche was making points of this kind. However, this interpretation does not capture what many commentators and lay readers typically take to be the main insights of Nietzsche’s text. For instance, when undergraduates read the Genealogy, they usually take with them the idea that Nietzsche’s history shows that much avowed concern with virtue, rightness and justice is less noble than it purports to be – it is motivated by some concoction of petty vengefulness, self-valorisation and resentment against powerful and high-status others. Here, it is Nietzsche’s claims about the particular interests and motives of the priests, warriors and slaves that is crucial, not merely the fact that none of these figures is divine or reliable.

How might these interests and motives play a role in Nietzsche’s critique of morality? Perhaps Nietzsche is assuming that, if moral norms were originally motivated by ressentiment, then this directly renders them objectionable by ‘tainting’ them in some fashion, even if those who conform to them nowadays are not motivated in the same manner. However, Nietzsche need not make this assumption. It is more likely that Nietzsche sees his historical story as relevant in a more indirect manner, as evidence of similar psychological dynamics in contemporary society. On such a view, genealogy is relevant to a critique of morality because it provides evidence that contemporary morality has objectionable features, such as bad motives, that are not themselves historical.

The idea that many avowed moral views have dubious motives is not a hard sell, particularly given modern internet culture. So one might wonder why one need turn to history to make this observation. There are two reasons. First, Nietzsche’s history helps us see these dynamics more clearly by telling a historical story in which they are present in a simple and unmasked form. While contemporary morality is overlaid with complexities and rationalisations, if we look to the past, we can better see psychological dynamics that have now been obscured. History, on this interpretation, is used to unmask the present.

Second, because we are less personally and emotionally invested in viewing past situations in a particular manner, we are better able to take a less credulous, more realistic perspective of it. While we might bristle at thinking that our political convictions are motivated by ressentiment, we are more likely to recognise this dynamic in historically distant others, which then enables us to recognise it more easily in ourselves. Historical perspective prevents us from giving in to wishful thinking.

These points form an important strand of Nietzsche’s thinking. However, there are challenges to reading Nietzsche as using history in this indirect, evidential manner. Such interpretations treat the past as merely a simplified version of the present, differing from contemporary society only in minor ways. Consequently, this approach overlooks the kinds of significant historical change and contingency that are central to historicist perspectives on our social practices. If this account of Nietzsche’s genealogy were the whole story, it would seem that Nietzsche himself would lack a historical sense. If we want to understand how Nietzsche’s Genealogy might honour such historicist assumptions, we should turn to the history of Nietzsche’s genealogical method itself. That is, we should return to philology.

Much philological research in Nietzsche’s time was interested in investigating the way in which ancient and sacred texts are complex composites, with diverging elements stitched together from conflicting sources. For instance, Julius Wellhausen argued that the Pentateuch, the Hebrew Bible, was a human artefact that could be decomposed into four independent sources, each of which originated significantly after Moses (who was previously thought to be the sole author, a kind of ghostwriter for the divine). This source criticism enables us to see the Hebrew Bible less as a unified work and more as an amalgam of distinct elements with differing histories. This information discourages looking to the Bible for a unified theology, and therefore encouraged taking a less theological approach to the Bible generally.

As a teenager at Schulpforta, Nietzsche learned this broad philological approach to ancient texts. For instance, his teacher Friedrich August Koberstein (himself a revered scholar and historian) suggested that he research a poem on the saga of the 4th-century Ostrogoth King Ermanarich. The poem is puzzling because some parts describe Ermanarich as a noble hero while others describe him as a coward and someone who murdered his wife. It is not obvious how readers are supposed to evaluate Ermanarich. Adopting a historical perspective, young Nietzsche argued that these conflicts arise from the fact that the poem does not have a single author but rather derives from a variety of sources – it is a layered construction with some parts from the Near East, others from Germany, as well as some from Denmark and Britain.

Nietzsche traces back different aspects of our moral framework to distinct sources

This broad approach to texts informs Nietzsche’s thinking about contemporary morality, which he describes in the Genealogy’s preface as a ‘long, hard-to-decipher hieroglyphic script’. When we look at our contemporary values, there are some ostensible tensions. For instance, many believe that excellent human achievements deserve special admiration and rewards, but also that it is only fair to receive special rewards for things that one has earned. But excellent human achievements are often due, at least partially, to innate talents that are not earned, so these views seem in tension. Much moral philosophy involves teasing out such intuitive judgments, finding tensions among them, and considering ways of resolving these tensions, much like a theological approach to the Bible involves identifying explicit and implicit theological claims in the text, finding tensions among them, and considering ways of resolving them.

However, Nietzsche’s philological approach is different. Like Wellhausen’s historical analysis of the Hebrew Bible, Nietzsche traces back different aspects of our moral framework to distinct sources. The perfectionist elements come from the warrior caste, the egalitarian ones from the priestly caste and slave caste, and other aspects of our moral framework – such as respect for ancestors – have still other sources. Rather than simply different strands coming together, we have a ‘document’ that has been rewritten and reinterpreted over time, often by those with complex and conflicting motivations. A philological approach to morality understands it as a complex amalgam rather than a unified evaluative framework.

This historical approach differs from more typical forms of moral philosophy because it does not assume that there is a unified answer to questions like ‘What is the good?’, at least if that answer is supposed to fit with many of our intuitive judgments. Rather, it brings out the competing strands of our moral thinking by providing an explanation of their presence that suggests that there won’t be a way to reconcile them. That is, just as a scientific philology of the Bible might undermine the presuppositions of Christian theology – that one will be able to construct a unified theology that fits sacred texts – so too a philology of morality undermines a presupposition of a certain strand of moral philosophy, that there is a unified moral theory that will make sense of our moral assumptions and practices. When one takes the historical perspective, much moral philosophy looks like it is engaged in a hopeless apologetic project of trying to reconcile what cannot be reconciled. There is no higher compromise between masters and slaves.

Now, if Nietzsche’s philological approach were relevant only to philosophical methodology, it might seem of little interest outside academic debate. However, this approach to morality does not just highlight a problem for contemporary moral philosophy. It also highlights a problem for us. For the fact that our modern moral views are fragmented and disunified itself poses problems. It means that it is difficult to act effectively and consistently, as there is no overarching framework for reconciling competing considerations in practical decision-making. It means that we might be committed to assessing ourselves according to conflicting criteria, ensuring that we are never able to measure up to the standards we set for ourselves. It sets us against ourselves. Nietzsche considered this kind of fragmentation and tension in our views a kind of illness, one of the ways in which modern society is sick.

Once one sees how the tools of philology can be applied to morality, it is easy to see how they can be extended to other parts of contemporary culture. If we examine the history of the norms that structure various social identities, we are often able to make salient forms of internal conflict that are latent in everyday life. For example, by examining the history of gender norms, we may more clearly discern tensions within contemporary conceptions of gender – eg, if you’re a woman, you are supposed to be both an angel of the house and a girlboss, and if you’re a man, you need to be an alpha while avoiding being toxically masculine. These competing norms often create conflicts within those who are invested in these identities, and clarifying the conflict may help avoid fruitless and frustrating attempts to reconcile these competing elements.

Of course, fragmentation and tension need not always be negative – there can be productive tensions, as Nietzsche recognised. Later theorists who have wanted to apply this philological approach to the cultural sphere have often aimed to emphasise its emancipatory potential. For example, understanding national histories as multifaceted genealogies, yielding political communities that are complex composites rather than unified cultures, enables one to appreciate the dynamism of cultural richness and challenge simplistic views of cultural homogeneity. ‘Unity’ is not a virtue in every domain.

Stepping back, a central puzzle about Nietzsche is why a self-styled ‘philosopher of the future’ should be so interested in the past. By examining the history of Nietzsche’s historicism, we can discern an answer. If employed critically, philology is not merely a tool for exploring the past but one for actively shaping the future.