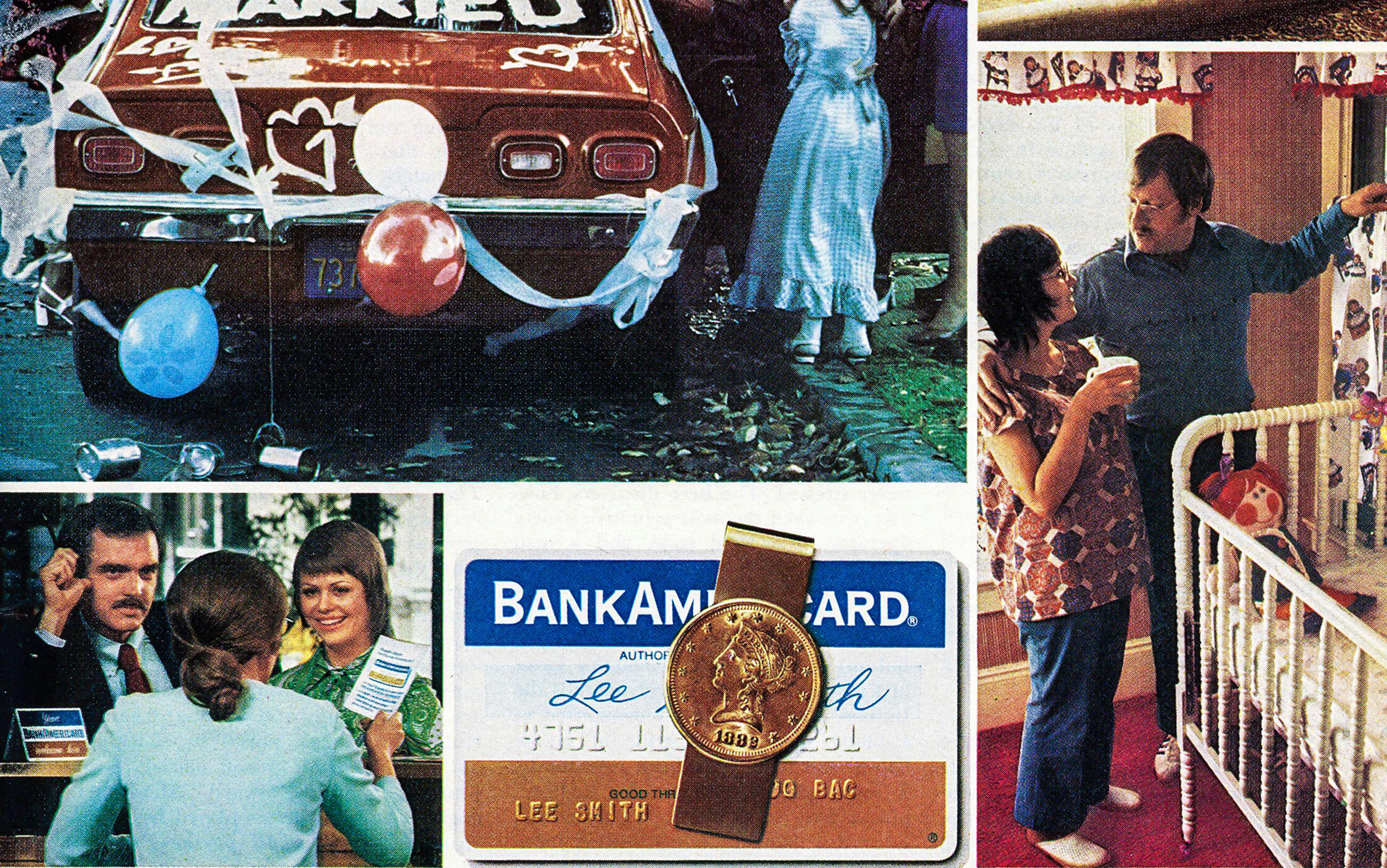

It has long been fashionable to say that the globe is shrinking. In the wake of the telegraph, the steamship and the railway, thinkers from the late 19th century onwards often wrote of space and time being annihilated by new technologies. In our current age of jet travel and the internet, we often hear that the world is flat, and that we live in a global village. Time has also been compressed. Timespans ranging from a few months to a few years determine most formal planning and decision-making – by corporations, governments, non-governmental organisations and international bodies. Quarterly reporting by companies; electoral cycles of 18 months to seven years; planning horizons of one to five years: these are the usual temporal boundaries of our hot, crowded, and flattened little world. In the 1980s, this myopic vision found a name: short-termism.

Short-termism has no defenders. Everyone seems to be against it, and yet proponents of alternatives are also in short supply. One prominent opponent of short-termism is Stewart Brand, founder in the 1960s of the Whole Earth Catalog and a leading cyber-utopian ever since. Among his visionary projects is the Long Now Foundation, based in San Francisco and founded in what Brand and his fellow foundationeers call 01996 ‘to creatively foster long-term thinking and responsibility in the framework of the next 10,000 years’. The extra zero alerts us to a longer timescale, not of decades or centuries but of millennia.

The Long Now Foundation does look to the past, for example with its ‘de-extinction’ project, Revive and Restore, to bring defunct species back to life using genomic technology. But Brand’s most imaginative solution to short-termism is to look further into the future. This is the principal message of the Clock of the Long Now, a slow-moving mechanism being built in a Texas mountain that will run for 10,000 years.

Looking forward into the future is also the strategy proposed by the Oxford Martin Commission for Future Generations, chaired by the former director-general of the World Trade Organisation, Pascal Lamy, and convened under the aegis of the Oxford Martin School at Oxford University. Last year, the Martin Commission issued its report, Now for the Long Term, ‘focusing on the increasing short-termism of modern politics and our collective inability to break the gridlock which undermines attempts to address the biggest challenges that will shape our future’. Again, the thrust was forward-looking and firmly turned to the future.

What Brand and the Martin Commission have missed is the need to look deeper into the past as well as further into the future. There are no historians on the board of the Long Now Foundation, nor were there any among the global luminaries assembled on the Martin Commission. The Clock of the Long Now points forward for millennia but has roots barely decades long; few of the examples of global problems in Now for the Long Term came from before the 1940s. Short-termism about the past apparently afflicts even those who attack short-termism about the future. Yet if historians have been absent from these initiatives, they can’t blame only the futurologists for their fate.

The humanities departments of our universities should be the place to go for a long look in the rear-view mirror. After all, universities have been among the most enduring institutions humans have created. The average half-life of a business corporation has been estimated at 75 years: capitalism’s creative destruction sees most companies crumble before they reach their centenary. The Spanish founded universities in Mexico City and Lima in Peru decades before Harvard and Yale were chartered, and 450 years later, both still exist. The first wave of university foundations in Europe occurred between the late 11th and early 13th centuries. And India’s Nalanda University in the northern state of Bihar was set up as a Buddhist institution more than 1,500 years ago: it has been recently refounded and had its first new intake of students this September. As Michael Spence, vice-chancellor of the University of Sydney, recently wrote, universities are ‘the one player capable of making long-term, infrastructure-intensive research investments’; compared with businesses, they are the only ‘entities globally capable of supporting research on 20‑, 30‑, or 50‑year time horizons’.

The mission of the humanities is to transmit questions about value – and to question values – by testing traditions that build up over centuries and millennia. And within the humanities, it is the discipline of history that provides an antidote to short-termism, by giving pointers to the long future derived from knowledge of the deep past. Yet at least since the 1970s, most professional historians – that is, most historians holding doctorates in the field and teaching in universities or colleges – conducted most of their research on timescales of between five and 50 years.

The novelist Kingsley Amis satirised this tendency towards ever more microscopic specialisation among historians as early as 1954 in Lucky Jim, the work from which all later campus novels sprang. Jim Dixon, an anxious junior lecturer, frets throughout the book about the fate of a well-polished article meant to jump-start his career. Its topic? ‘The Economic Influence of the Developments in Shipbuilding Techniques, 1450 to 1485’. ‘It was a perfect title,’ the narrator tells us, ‘in that it crystallised the article’s niggling mindlessness, its funereal parade of yawn-enforcing facts, the pseudo-light it threw upon non-problems.’ Within only a couple of decades, any PhD supervisor on either side of the Atlantic would have discouraged a topic of such breadth and complexity, spanning almost four decades, as foolhardy in the extreme.

When historians first became professionalised in the late 19th century, it was still possible for them to tackle subjects of genuine breadth and ambition. In the US, Frederick Jackson Turner – later famous for his ‘frontier thesis’ of American national development – wrote his PhD thesis in 1891 on frontier trading posts from the 17th to the 19th centuries. In 1895, W E B du Bois, the first African-American to receive a PhD from Harvard, studied the suppression of the African slave-trade from 1638 to 1870 for his doctoral research.

A recent survey of some 8,000 history dissertations written in the US since the 1880s has shown that the average period covered in 1900 was about 75 years; by 1975, that had shrunk to about 30. (Matters were even worse in the UK, where PhD students had less time to undertake their research and writing than most US students, and timescales were even more abrupt.) Only in the past decade has it rebounded again to somewhere between 75 and 100 years.

There were many reasons for historians’ turn towards a shorter vision of the past. A competitive job-market meant that newly minted historians had to show their mastery of archives – sometimes, the more obscure and inaccessible the better – as well as their command of a fast-growing body of scholarship. If you did not get your hands dirty with original documents, you were hardly a historian at all. Such experience was hard-won and could be undertaken only for smaller slices of time and space.

Around the same time, the practice of micro-history became prevalent throughout the historical profession. Books such as Carlo Ginzburg’s The Cheese and the Worms (1976), Robert Darnton’s The Great Cat Massacre (1984), or Natalie Zemon Davis’s The Return of Martin Guerre (1984) revealed fascinating puzzles in the cultural life of our ancestors, told through startling stories or seemingly incomprehensible incidents, all unpacked using tools first forged by ethnographers and anthropologists.

A focus on exceptional individuals and events dovetailed with the ‘suspicion towards grand narratives’ that the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard gave in 1979 as the definition of postmodernism. Large stories, told across long sweeps of time, became both unfashionable and unfeasible, at least for anyone claiming professional competence as a historian. Grand narratives were associated with the grim determinism of Oswald Spengler, author of Decline of the West (1918), or the globe-scanning schemes of Arnold J Toynbee, author of the 12-volume A Study of History (1934-61). Historians might supply surveys in their classrooms or textbooks, but lack of familiarity with the sources – all of them, in their gritty detail – seemed to guarantee grandiosity and superficiality at the expense of fine-grained detail and complex reconstruction.

This move towards shorter timescales marked a double retreat, the first from the core mission of history since classical times, the second from the influential practice of post-War French historians to study longer-term histories. For more than 2,000 years, from the time of Thucydides to the middle of the 20th century, one of the primary purposes of learning about the past was to orient oneself towards the future. Cicero wrote in the first century BCE that history was a ‘guide to life’ (magistra vitae) – for politicians, their advisers, and for citizens.

Moving to a Short Past, without an eye to action or a tilt towards the future, broke historians from their long-developed habit of informing the public sphere

This was the classical spirit in which Machiavelli and his contemporaries wrote their histories, whether of ancient Rome or of their own city-states such as Florence, taking lessons from Rome’s arming of the plebeians or its strategies for territorial expansion when considering the destinies of their communities. It was also the aim of historians in the Enlightenment, among them David Hume, Voltaire, and even Adam Smith, whose Wealth of Nations was at its heart a history of Europe and its overseas empires written to inform debate about the commercial future of Europe and its colonies and published in the fateful year of 1776.

After the French Revolution, practising politicians in Britain and France often turned to the past to shape current debate, with leading politicians – for example, François Guizot, Adolphe Thiers and Jean Jaurès in France, and Thomas Babington Macaulay and Lord John Russell in Britain – writing histories of their own revolutionary pasts to shape their national futures. History was a ‘school of statesmanship’, in the words of J R Seeley, the Regius Professor of Modern History in late-Victorian Cambridge. In the same moment, a text such as Alfred Thayer Mahan’s The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783 (1890) could become the textbook on military strategy in naval colleges in the US, Germany and Japan, assigned in classrooms for decades. Moving to a Short Past, without an eye to action or a tilt towards the future, marked professional skill but also broke historians from their long-developed habit of informing the public sphere.

More immediately, the Short Past marked a retreat from what the great French historian Fernand Braudel had called the longue durée (meaning, the long term). Braudel remains famous even now, and even beyond historians, for his multilayered, ocean-spanning history of the Mediterranean in the age of Philip II, published in 1949. Between 1940 and 1945, Braudel planned his masterwork while he was held in detention camps in Germany where he had lectured to his fellow inmates on the course and meaning of history. He later reflected that the unchanging rhythms of internment – the repetitive routines, seemingly without hope or reason – forced him to think along longer timescales in order to recover hope beyond the tedium of the daily round.

Camp life strongly shaped Braudel’s vision of the Mediterranean past, which he told as three successive histories: a ‘seemingly immobile’ story of the unchanging physical environment; a ‘gently paced’ history of states, societies, and civilisations; and the more conventional narrative of those ‘brief, rapid, nervous oscillations’ called events. For Braudel, events were the ‘froth’ on the waves of time but they should not be confused with history, which took place at much greater depths and often hidden from view.

Braudel baptised this movement ‘la longue durée’ in 1958, as a shot in an academic and institutional power-game being played out in France while the Fourth Republic was giving way to the Fifth amid domestic and international crises. Braudel bemoaned what he saw as a crisis of the human sciences, in which knowledge was exploding, data had got out of control, intellectual fields became more inward-looking, and many scholars focused only on the short-term, the here and now, and the politically expedient.

As a solution to this crisis, Braudel offered history as the only discipline capable of explaining how immediate events fit into larger, indeed, longer patterns. He charged that economists, like many of his fellow historians, concentrated too much on spans of 10, 20, 50 years at most. That was no way to see how critical events emerged from deeper structures. The answer, then, was to work on a different horizon, a history measured in hundreds or even thousands of years: the history of a long, even very long duration (l’histoire de longue, même de très longue durée).

The longue durée soon took on a life of its own as a shorthand for the long term, even in English. It betrayed Braudel’s academic agenda to put the study of history at the forefront of the human sciences, as he battled against anthropology (and Claude Lévi-Strauss) and economics (with its embrace of mathematics) for prestige and national funding. His agenda to enthrone the past also fit nicely with the simultaneous movement in France to promote the future, with futurology emerging as a science. Its leading proponent was Braudel’s close friend Gaston Berger, who as director-general of French higher education in the 1950s held the purse-strings for institutes of advanced study.

Every action spawns a reaction. The Short Past of the 1970s was a response to the longue durée of the 1950s. It might even have had elements of an Oedipal revolt by newly politicised students in the wake of the events of 1968 who turned against the shibboleths of older historians. The generation of ’68 trained a new cadre of scholars for whom archival immersion, telling detail, and the reconstruction of short-term narratives mattered more – and gained more prestige – than analyses of broad structures or extended time-spans. The gains of the shift to the Short Past were obvious: greater rigour, more original topics, an engagement with the experiences of communities – women, the enslaved, ethnic minorities, among others – that had been sidelined from more traditional histories. But there were also costs to historians in terms of their public profile and even their political influence.

In the 19th century (as for centuries before) politicians had written history. In the 20th century, that tradition did not entirely expire – think of Winston Churchill, who won a Nobel Prize in Literature largely for the histories written around his years in public life – but more often historians were consulted for their political wisdom, nationally and internationally. For example, the Fabian historians Beatrice and Sidney Webb helped to shape London’s political institutions thanks to their knowledge of English local government since the Middle Ages. Likewise, their colleague at the London School of Economics, R H Tawney, could be sent on a mission to study land reform in China in 1931 because he had studied the enclosure of the commons in 16th-century England.

The longue durée informed political decision-making and institution-building in the first half of the 20th century in ways that it would not in the second. The move away from history was partly due to the ascendancy of other forms of academic advice, most notably from economists. But it was also partly self-inflicted, as historians refined their work to make the past unusable for political purposes – at least, the purposes of national and international governance. Long-term narratives still had a hold but they came not from members of history departments but from global think tanks: from demographers deployed by the Club of Rome in the 1970s or by futurologists employed by the RAND Corporation in an age of ‘limits to growth’ and the ‘population bomb’. Theirs was a ‘dirty’ longue durée, produced more for present purposes than for its critical stance towards contemporary pieties. These non-historians dealt with an impoverished array of historical evidence to draw broad-gauge conclusions about the tendency of progress.

Why not toss all those introverted but highly competent monographs and journals articles onto a bonfire of the humanities?

Long-range histories by historians never disappeared entirely from libraries or bookshops: Braudel, for one, continued to write multi-volume histories of capitalism and civilisation into the 1980s. Even professionals continued to teach survey courses on ‘Western Civilisation’, US or UK history over many decades and centuries. Their efforts nonetheless collided with the economies of professional prestige and promotion. In the era of the Short Past, microhistory prevailed over macrohistory. The big picture often got short shrift.

This ‘Age of Fracture’, as the US intellectual historian Dan Rodgers called it in 2011, left a long legacy of short-termism. All kinds of grand narratives had lost steam: Marxism, modernisation theory, the rise and fall of civilisations, the rhythms of the business cycle, all failed to have explanatory power. Always sensitive to changes in the atmosphere, leading historians in the early 1980s began to criticise the unintended consequences of the move to a Short Past. ‘Historical inquiries are ramifying in a hundred directions at once,’ complained Bernard Bailyn, the Harvard Americanist, in a presidential address to the American Historical Association in 1981. ‘[S]ynthesis into a coherent whole, even for limited regions, seems almost impossible.’ Across the Atlantic, the rising young British historian David Cannadine concurred, as he condemned a ‘cult of professionalism’ that meant ‘more and more academic historians were writing more and more academic history that fewer and fewer people were actually reading’. Why not toss all those introverted but highly competent monographs and journals articles onto a bonfire of the humanities?

Within 25 years, the laws of academic thermodynamics seemed to create yet another countermovement. The past decade has seen a revival of grand narratives, large questions and broad – sometimes even universal – histories. After retreating to problems on biological and biographical timescales, historians are now working on spans of time that are climatological, archaeological and cosmological in scope.

The Anthropocene – the still-controversial geological era in which human beings have comprised a collective actor powerful enough to affect the Earth and its environment on a truly planetary scale – is already an object of historical enquiry, extending back at least to the late 18th century and the origins of greenhouse-gas emissions after the Industrial Revolution. A growing group of scholars is pursuing ‘Deep History’, the story of the human past over at least 40,000 years, which deliberately erases the boundary between ‘history’ and ‘prehistory’ using the tools drawn from genetics, archaeology, biochemistry and neurology. Grandest of all is ‘Big History’, a movement that has attracted the attention of Bill Gates for its embrace of a story that stretches back to the beginnings of the Universe itself. As the founder of Big History, the Australian historian David Christian, has noted, this is the ‘longest durée’ that historians can possibly imagine or reconstruct.

Historians do not have to go as far back as the Big Bang to escape the Short Past. Long-range histories on scales of a century to three millennia abound again: of anti-Judaism from ancient Egypt to the present, and the ‘first’ 3,000 years of Christianity; of guerrilla warfare from ancient times to the present, and of strategy from chimpanzees to game theory; of genocide ‘from Sparta to Darfur’, and racism from the Middle Ages to our own times. Most of these ambitious histories combine the attention to detail and context that characterised microhistory with a desire to recount stories and structures that can be understood only in the longue durée.

The opportunity to array the longue durée against endemic short-termism has arrived with a vengeance. The most pressing problems of our time – for example, climate change, crises of global governance, the proliferation of inequality – have no simple solutions because they have such deep roots. But disentangling is what historians do. We are trained to balance different forms of data against each other, to be alert to the complexity of causality, to consider how long-term structures interact with short-term determinants. Where other social scientists value parsimony – the most stripped-down, cleanest explanation or analysis of a problem – historians prefer profligacy, a multiplicity of sources against which to calibrate causation and to foresee the conflicted futures arising from multiple contested pasts.

seen in a 200-year perspective, rather than over three decades, inequality appears regressive not progressive, and has been getting only worse

Many adjacent human sciences, and even the natural sciences, have undertaken a historical turn of late. The era of big data is an age of proliferating evidence about the human and non-human past: statistical, verbal and physical, from massive verbal corpora of digitised texts, via tweets and climate data, to ice-cores, tree-ring data and the human genome. Some of our colleagues are even deploying the longue durée to undermine some of the most cherished illusions of their disciplines.

Take Thomas Piketty, the French economist whose Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2014) became a global intellectual sensation when it exposed the fallacy of the ‘Kuznets curve’ and laid bare the dimensions of ever-expanding inequality in advanced societies. The mid-20th-century economist Simon Kuznets had argued that capitalism led inevitably to increasing prosperity and therefore to decreasing inequality. Kuznets’s data-set was confined to about 30 years in midcentury, including the aftermath of the Second World War. Piketty demolished Kuznets’s universalising conclusions by showing how limited were his horizons and how local was his data: seen in a 200-year perspective, rather than over three decade, inequality appears regressive not progressive, and has been getting only worse since Kuznets won a Nobel Prize in Economics in 1971. Pulling out the focus radically changed the picture: with good reason has Piketty called his book ‘as much a work of history as of economics’.

The public future of the past is now firmly in historians’ hands. History as a discipline is poised to recover its ancient mission as the guide to life but in a new guise as a critical human science, capable of judging data, incorporating it into complex narratives, and presenting its conclusions in forms accessible to the widest possible range of publics as well to those who make the policies that shape all of our lives. Historians now have more evidence – more data – in more forms available to them than ever before. Using digital materials and the tools to make sense of this data, historians can perform analytical feats that would have required a lifetime of immersion a generation ago.

The return to the longue durée is not just feasible, it is imperative: feasible, because of the resources to hand and the means to make sense of them; imperative, because of the proliferation of big data in every aspect of our lives and the necessity of fighting back critically against those who might wield its powers of shock and awe against us. The world might have shrunk but the collective challenges facing its people have grown only more apparent, in all their complexity. At a time of ever-expanding inequality – within societies, if not between them – when international institutions have reached breaking-point; and when anthropogenic climate change threatens our water and our food, our political stability and even the survival of our species, even the most basic apprehension of our condition demands a scaling-up of our enquiries.

The History Manifesto is published by the Cambridge University Press, and is available as a free download here.