So I’m posted up, sharing a sandwich and a cigarette with a friend in one of the most dangerous neighbourhoods in America, and my phone buzzes. On the other end is one of my old professors asking me to tell one of my wild childhood stories at the Stoop Storytelling Series, at Center Stage in downtown Baltimore.

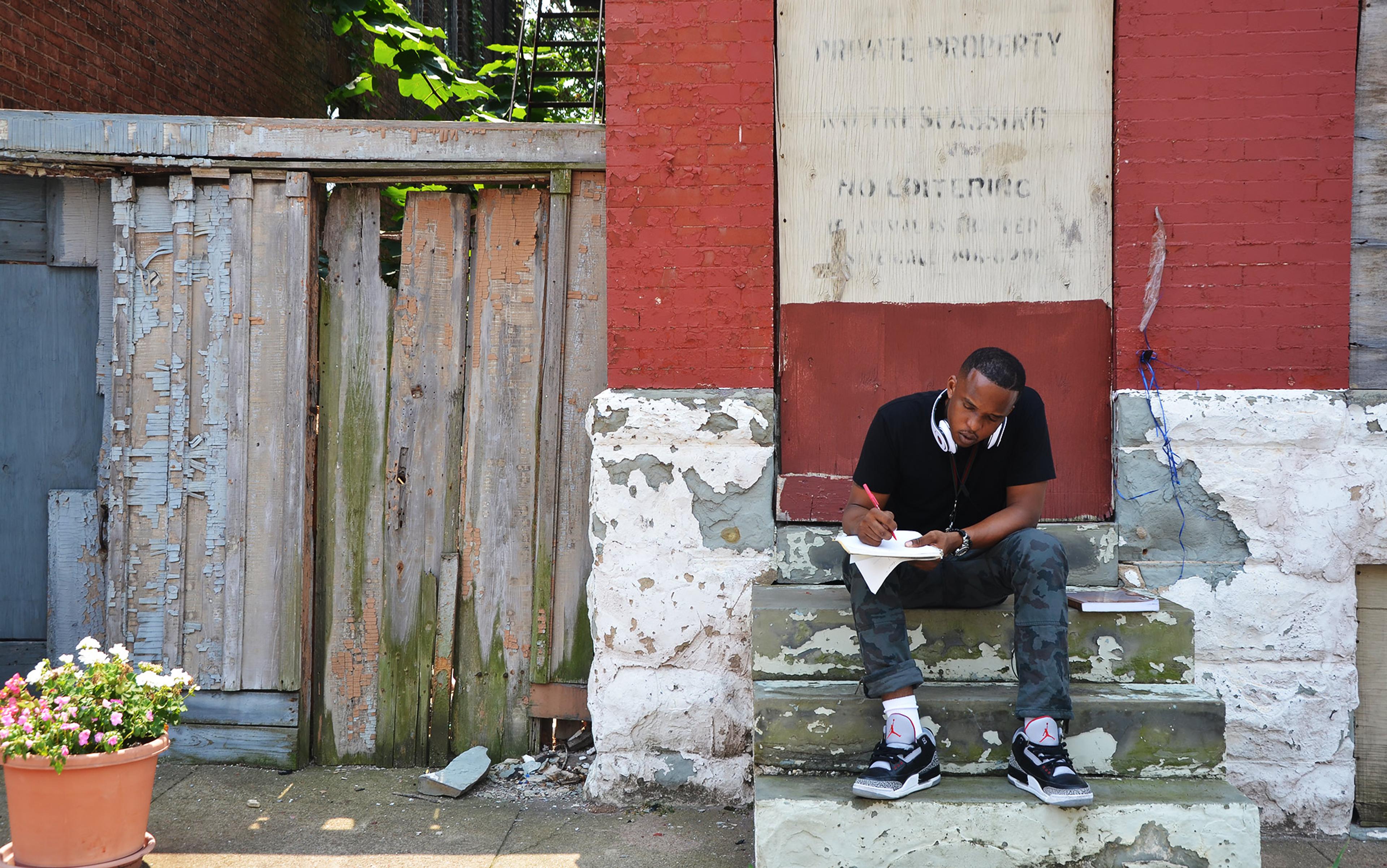

A stoop show, I thought: kind of like what I do on the corner in my own neighbourhood every day. I’m always surrounded by stoops, Baltimore stoops made of cracked and chipped marble steps where all we do is tell street stories: who’s getting money, who’s going to jail, who murdered who, whose album is hot, who is that girl, who’s driving what, and who’s coming home from jail.

This would be easy, the same thing, but in someone else’s neighbourhood. I agreed to it like I agreed to the last 15 opportunities that fell in my lap. I’d recently written ‘Too Poor for Pop Culture’, an essay that went viral and made me semi-relevant on the internet and the man to know on the local scene. I’d learnt that exposure and platform are key, so I looked forward to the event.

The day of the show rolled round and I was backstage with my fellow cast members and storytellers. These guys were Easter-sharp, with starched button-ups and wingtips; the women matched them in pumps and flashy adult versions of their prom dresses.

Obviously, I missed the dress code memo because I walked in wearing a black hoodie and some black Air Jordans. But no one really cared about my outfit: they greeted me with gifts, praise and love when I arrived backstage.

One of the organisers hit me with some drink tickets so I could get a little buzz before the show. I grabbed them and blasted into the lobby to redeem. That’s when I realised. This is one of those events.

By ‘those events’ I mean a segregated Baltimore show that blacks don’t even know about. I walked through a universe of white faces wondering, how is this even possible? How could we be in the middle of Baltimore, a predominantly black city where African Americans make up more than 60 per cent of the population, at a sold-out event, with no black people – except for me and the friends I brought?

I swallowed my drink and grabbed another for the stage. The hostess gave me an amazing intro and welcomed me to the mic. I walked up and said: ‘This ain’t the stoop I’m used to. There’s no pit bulls, red cups or blue flashing lights, but I’ll make it work!’ I paused, took a look at the crowd and honestly felt like I wasn’t in Baltimore.

My black friends call it Baldamore, Harm City or Bodymore Murderland. My white friends call it Balti-mo, Charm City or Smalltimore while falling in love with the quaint pubs, trendy cafés and distinctive little shops. I just call it home.

We all love Baltimore, Maryland. It’s one of those places that people never leave – literally. I know people, blacks and whites, who have been residents for 30-plus years and haven’t even been as north as Philly or as south as DC.

Baltimore is one of the few major metropolitan cities with a small-town feel. The town was founded in 1729 and named after the Englishman Cecilius Calvert, better known as Lord Baltimore. In the years that followed, Germans and Scots settled the cheap land, which was too poor for tobacco farming but good enough for wheat. Proximity to water helped Baltimore flourish, with a thriving ship market at Fell’s Point, now a hip waterfront area.

Is Baltimore a place split on ideologies because it’s too south to be north and too north to be south?

Eventually, Baltimore took off in a major way, and as industry grew so did the need for slaves. By 1810 Baltimore had 4,672 slaves, mostly hired out by cash-strapped owners from upper Maryland. In the heyday of the antebellum South, before the Civil War, some of those Baltimore slaves made enough money on the side to buy their own freedom and eventually the freedom of their family and friends.

Maryland sided with the Union during the Civil War by not declaring secession, even though it was a slave state – though some people in southern Maryland joined the Confederates anyway to keep their slaves and their tobacco farms. Some Confederate supporters attacked Union soldiers, causing 12 deaths and the Baltimore riot of 1861. After that, the Union Army had to step in and occupy Baltimore until 1865.

Is this how the two Baltimores began? As a place split on ideologies because it’s too south to be north and too north to be south – was this the start?

It is now 149 years later and nothing has changed. I went to all-black schools, lived in an all-black neighbourhood, and had almost no interactions with whites other than teachers and housing police until college, where I got my first introduction to the other Baltimore.

My SAT scores and grades were exceptional for an east Baltimore kid. This gained me acceptance into schools I probably wouldn’t have been admitted to if I weren’t a ghetto kid. Thirsty for a new experience, I wanted to go to an out-of-state college. But my plans were derailed when, months before my high-school graduation in 2000, my brother Bip and my close friend DI were murdered. I became severely depressed and rejected the idea of school.

Most of my family and friends came around in effort to get me back on track. My best friend Dre hit my crib everyday.

I met Dre way back in the nineties. His mom sucked dick for crack until she became too hideous to touch. Then she caught AIDS and died.

Dre’s my age. He had so many holes in his shoes that his feet were bruised. I started giving him clothes that I didn’t want, and he stayed with us most nights. We became brothers.

At 13, Dre started hustling drugs for Bip and never looked back. He loved his job. Dre was organised, he recruited, and he outworked everyone else on the corner. Like a little Bip, Dre beat the sun to work every morning: 4am every day in the blistering cold, with fist full of loose vials. His workload tripled after Bip passed, but he called everyday.

‘D, how you holdin’ up, shorty?’ said Dre.

‘I don’t even know. Man, I been in this house for weeks,’ I replied.

‘Naw, nigga, get out. Get a cut, nigga, go do some shit! Least you still alive!’

‘You right,’ I said as I sat on the edge of my bed. ‘Wet floor’ signs were needed for my tears.

‘What the fuck, Yo, you cry everyday?’ Dre said.

‘Naw, well no, shit. I dunno.’

‘Yo anyway, I’m gonna murder dat nigga that popped Bip. Ricky Black, bitch ass. So go live, nigga, get some new clothes, pussy or sumthin’.’

I’m not a killer. Or am I? I am capable of hate, and I am a direct product of this culture of retaliation

I picked my head up for the first time in days. I didn’t know my brother even had static with Ricky Black. They played ball together a week before Bip died. But it didn’t matter if Dre killed Ricky, or I did, because someone would eventually.

Murder made Dre smile theatrically; he leapt from his seat. ‘Nigga, I keep the ratchet on me,’ he said, lifting his sweatshirt to show me the gun gleaming on his waist.

I told him he was crazy, but I didn’t care. I wouldn’t commit that murder – I’m not a killer. Or am I? I am capable of hate, and I am a direct product of this culture of retaliation – a culture that won’t let me sleep, eat or rest until I know that Bip’s killer is dead.

‘Be careful,’ I said.

‘You should think about school, D,’ said Dre on his way out the door. ‘Bip would like that.’

He was right. My brother always wanted me to attend college: I owed Bip that.

I decided to stay in state to be close to family, so I attended Loyola University, a local school on the edge of the city.

I always thought college would be like that TV show, A Different World. Dimed-out Whitney Gilberts and Denise Huxtables hanging by my dorm – young, pure and making a difference. I’d be in Jordans and Jordan jerseys or Cosby sweaters like Ron Johnson and Dwayne Wayne, getting As and living that black intellectual life on a beautiful campus. No row homes, hood-rats, housing police or gunshots: just pizza, good girls and opportunity. I could even graduate and be ‘The Dude Who Saves the Hood!’

I’d clearly say: ‘Excuse me, where is the book store?’ And they’d look back with a twisted face, like: ‘I don’t understand you’

A plethora of white and Asian faces smirked at me as I walked across campus the first day. This was a different world, but not the world I was looking for.

There were some other black dudes there, but they weren’t black like me. They spoke proper English, wore pastel-coloured sweaters, Dockers chinos and boat shoes, carried credit cards, chased Ugg-booted white girls, played sports other than basketball and talked about Degrassi – what the fuck is Degrassi?

I wore six braids straight back like the basketball player Allen Iverson, real Gucci sweat suits, and a $15,000 mixture of mine and Bip’s old jewellery. The other students looked at me like I was an alien. I’d walk up on a student and clearly say: ‘Excuse me, where is the book store?’ And they’d look back with a twisted face, like: ‘I don’t understand you. What are you saying?’ And I had this dance with multiple students every day until I mastered my ‘Carlton from The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air’ voice.

I related to no one, so I talked my friend Nick, who dropped out of middle school, into hanging around campus with me.

‘Yo D, if any of these people act dumb, even the da principal, tell me. Swear to God, I’ll fuck ’em up for you, Yo.’

‘Colleges have deans, Nick, not principals, but I guarantee I won’t have any problems here.’

I laughed as we sat in Nick’s Camry. His face was stone. I cracked the door, split a blunt down the centre with my ring finger and dumped its guts on the sidewalk. We’d sit a block away from the school and burn two Ls of dro mixed with hash, and then it was school time.

Clean and high, I’d float through Loyola. Some of the students were racist – not to my face – and it seemed like my professors made sure I knew I was the only black person from low-income housing on their planet. My philosophy teacher was the worst. One time he asked: ‘What sport did you play to get into here?’ I fantasised about having Nick pistol-whip him, but he was only a pedestrian on my road to bigger goals.

I tried to adjust to the campus culture by attending basketball games and buying a grey Loyola hoodie; I bought Nick a black one. Together we sat, emotionless, through home games – underwhelmed by the basic style of play and unaffected by the school spirit that shook the gym. Loyola students got excited over made free throws and baseline jump shots. Hood dudes like us needed thrills – rim-breaking dunks, spin moves, shit talking, finger pointing and ankle-breaking crossovers.

Eventually, I met some cool white boys to smoke weed with. Tyler stuck out the most. He was a freshman like me but already had a hold on the campus. Girls giggled when he spoke, and most of the other freshmen lived and died for his approval. Initially we met in the athletics centre. I was shooting jumpers and Nick was rebounding for me. Tyler walked up and said: ‘Nice shot. You guys gamble?’

‘Shoot his head off, D! Shoot his head off, D!’ chanted Nick. Tyler and I went $5 a shot for an hour or so and I think he beat me out of $200 or $300. I paid him and he gave me $100 back.

We’d walk in and the mood would change. They’d call us bro and brotha, and give us too many handshakes

‘What’s this for?’ I said, rejecting the money. He explained that he had gambled with black guys before and he noticed that the winners always give the losers a little something back. Then he said: ‘Besides, you guys smell like Jamaicans! Can I get some of that?’ The three of us walked back to Nick’s Camry and smoked some joints. Tyler thought the bud was decent; Nick and I always had it so we exchanged numbers and ended up building a relationship.

Sometimes we smoked and talked shit to girls together, or beat the shit out of the squares that hung around in the athletics centre at basketball. Tyler even took me to his crib in Bolton Hill, with beautiful brownstones that ranged from $300K well into the millions.

I really liked Tyler but most of his friends were hard to take. They’d invite me and Nick to campus parties. We’d walk in and the mood would change. They’d reference Dr King and then Dr Dre, and call us bro and brotha, and give us too many handshakes. They tried to imitate us so we felt more comfortable, but it just felt condescending. The good part is that we never got into any fights and the N-word never slipped out. These parties got old to us really quick so we stopped going.

Doing homework and adjusting to this new world helped me deal with my losses a little, but I still had sleepless nights where I sat in the park until the sun woke me, wondering why I was alive and my brother wasn’t, why couldn’t Nick study and be a student too, why was I losing so many friends, and why I never got a chance to tell these people what they meant to me.

By mid-semester, I was sick of school. The work wasn’t hard, but it was boring as that show M*A*S*H, and trying to assimilate had become exhausting.

What would my brother say if he saw me hanging around this campus with Zack Morris and AC Slater, laughing at jokes I hated, listening to stories that bored me, going to wack basketball games, slowly conforming – being a good negro. Referencing Degrassi!

I showed him how our operation worked and who played what roles, how we changed shifts, different ways we incentivised hard work, and our methods for staying out of prison

So I said fuck it and stopped going. I had some money put up. Roughly $50,000 left behind in my brother’s stash. I took that along with some cocaine he left in his safe and dived right into the family business as a full-time crack, heroin and coke dealer.

Tyler hit me on the phone a month or so after I stopped showing up and said: ‘D, what the fuck, man? You’re just not going to come back?’

He needed some weed so I invited him down to my neighbourhood. After living in Bolton Hill all his life, my Baltimore blew his mind. He knew some black guys but had never really kicked in a housing project.

Tyler leaned against the gate and saw a bunch of Baptist churches, dirty little Korean stores with 30 teenage dope-dealers clogging the doors and the corner. Singing-and-dancing-and-dying dope fiends wandering around and bumping into each other like Thriller. Thirty-year-old pregnant grandmas. Dudes in Nikes waving automatic weapons. Unsupervised children, some barefoot and trying not to step on glass like we in a third-world country. And us: me and my crew.

I showed him how our operation worked and who played what roles, how we changed shifts, different ways we incentivised hard work, and our methods for staying out of prison. He was infatuated to say the least.

Shortly after, Tyler discovered a void in the raw coke market throughout the Loyola and Johns Hopkins/Charles Village area, and he wanted to join our operation. I set him up with coke and we never looked back. Tyler moved more coke in a week than most of my street people could move in a month. He built a huge clientele consisting of everyone from students to professors. We were all making crazy money and that’s how I really discovered the other Baltimore.

Black Baltimore is all about Grey Goose vodka, Hennessey cognac, crack sales, making money and running to the outskirts of the city, playing basketball, paying $40 to get into parties with $15 drinks, cookouts, corner stores, being harassed by cops, pit bulls, dirt bikes, church, diabetes, and staying in black areas.

White Baltimore, which in most cases is only two miles away from these black areas, is all about Ketel One or Stoli vodka, Jack Daniel’s whiskey and Coke, sniffing coke, labradors, eating outside, free entrance into clubs where you buy one drink and get another free, barbecues, free-range chickens, playing Frisbee, jogging, being loved by cops, and staying in white areas.

For years, Tyler and I worked the whitest areas in the city – Fell’s Point, Canton and Federal Hill. I even stacked enough cash to move out of the hood into a Bolton Hill brownstone similar to the one Tyler’s parents owned. When I told the homeboys where I lived, they thought it was more than 100 miles away, but it was only five miles from where I hung every day.

Living in Bolton Hill taught me a lot about our city and the role that segregation plays. I liked to bring 10 or 15 of my boys from my old neighbourhood up to my place to show them a little experiment that I figured out. I’d wait to around midnight and take a large, full trash bag out to the front of my house, cut it open and dump its contents all over the street. Then we’d smoke, drink, club, or whatever, but by 2 or 3am, all of the trash would be gone. The city would come through and pick up everything, leaving the front of my house squeaky clean.

I was sick of funerals, wasting days on corners, wondering when the cops would finally bag me or when it would be my turn to die

Then I’d do the same thing with a bag of trash in the black neighbourhood closest to Bolton Hill called Marble Hill. And the trash would sit. It would sit for days, unless residents cleaned it up. Marble Hill was known for being more dangerous, but Bolton Hill had more cops patrolling, in addition to better-kept parks and first priority when it came to snow removal.

During those years I lived in Bolton Hill, I also hung with Nick on a corner in the hood. Different sets of crews would come and go: some died off and went to prison but Nick maintained until 2004, when he asked me to put $60K of my own money with $100K of his and another guy’s cash into this big deal that could get us 10 bricks of cocaine and set us straight for life. I couldn’t afford it and I didn’t want to do it. I was thinking enough was enough around the time he was thinking expansion. I was sick of funerals, wasting days on corners and wondering when the cops would finally bag me or when it would be my turn to die.

I kept selling the little bit of drugs I had tucked away while Nick raised his money through an old-school approach. He hit every block from east to west, shaking down dealers, jamming his gun down throats, and emptying the pockets of anyone selling anything. I heard he even hung a kid named Tevin out of a window for $300: any and every thing to raise that money.

We have a saying in east Baltimore that goes: ‘Stick-up kids don’t last long’– and it’s right. Some guys from one of the many crews Nick robbed caught up with him and blew his brains out on Ashland Avenue, steps away from his grandma’s house. I got the news while visiting family in LA, and that was the beginning of the end for me.

Eventually, I lost contact with Tyler, lost the house in Bolton Hill, and ended up back in the hood where I started out. I decided to go back to school in hopes of finding a job and getting a better life.

This time, I attended the University of Baltimore, which is a semi-mixed school. UB ended up being a better fit for me than Loyola. It wasn’t A Different World, they had few black professors, and the white students at UB knew nothing about the Baltimore I’m from. But it was a mix of working people who wanted to better themselves through education, and I connected with them because of all the game I learnt from Tyler.

We are all gunning for the same things, but taking different roads and using different languages along the way

UB is a commuter school in the heart of midtown, and you’d be surprised to see such a small number of black students and professors at a school in the middle of Baltimore. But it’s true, the segregation continues. It’s evident in every classroom – the blacks sit with blacks, and the whites sit with whites. We’d work together on class assignments and presentations, and then, when we would go celebrate, the whites would go to their bar and we would go celebrate at ours.

My experience at Johns Hopkins, where I finished my Masters of Science in Education, felt more extreme. I walked through the hallway on my first day in 2010 and a woman looked me up and down, stopped me and said: ‘Excuse me, sir. Someone threw up in the women’s bathroom. Can you handle that? Thank you.’

I knew what she thought. I’m a black man at a white school, meaning I’m a janitor. I looked her in the eyes and said: ‘I believe in humanity,’ before walking away. The rest of my experience at Hopkins was just like that, but I must admit being there helped me master what I already thought I knew about the other side of Baltimore.

Simple communication, which I perfected at Hopkins, was the key. Underneath it all, I found, the privileged whites and Asians at Hopkins were the same as the black dudes in my neighbourhood. We all wanted love, success, purpose and opportunity. We are all gunning for the same things, but taking different roads and using different languages along the way. Learning how to communicate with people so far removed from my reality made me smarter, and now I’m an expert. I can communicate in the roughest housing projects because of my origin, and in the whitest neighbourhood because of my college experience and my time with Tyler selling good coke, and now I’m doing an event like the Stoop.

The crowd at the Stoop Storytelling Session must have been drunk: they laughed at everything I said to the point where I’m considering a career as a stand-up. ‘Oh yeah, and black people! There are no black people on this stoop! I’m not sure if you guys noticed or not!’ It was the last joke I gave before I dove into a story about me at 12 being robbed at gunpoint for my dirt bike.

My family didn’t panic or call the cops – they strapped up with guns, found the dudes and retrieved my bike. And even though we illegally took back my stolen bike, the overarching theme of family looking out for family connected us all. The audience at the Stoop got my perspective and had a unique chance to be invited to my side of Baltimore. It was all relatable, and the two Baltimores felt like one – but only for that night. Because after the show, I travelled back to my Baltimore and they returned to theirs.

Names and some locations have been changed.