For the workers who are curious why their wages have not increased in the past decade – while the incomes of some, such as footballers, have soared – the Bank of England’s website has a reassuring message: ‘There is a method to this madness: the economic theory of supply and demand’. The bank’s website provides an ‘idiot’s guide’ to the economy that explains how ‘Supply and demand is a bit like an economist’s version of the law of gravity. It decides how much everything costs: a cup of coffee, a house and even your salary.’

The US Federal Reserve Bank provides similar explainers for Americans who want to understand how their country’s wealth is created or allocated, including a colourful downloadable infographic that shows how higher prices create additional supplies of goods, and lower prices create additional demand. On its website, the International Monetary Fund notes that supply, demand and price are ‘magic words’ that make the economist’s ‘heart beat faster’.

For the economists in the neoclassical tradition, as most are, the world can be understood as a series of supply-and-demand curves – the X-shaped graphs that Alfred Marshall first made for his book Principles of Economics (1890) and that now litter almost every chapter of almost every economics textbook. Humans might be occasionally irrational but, en masse, orthodox economics says they respond to prices in a consistent and proportional way. People have what economists call ‘price elasticities’ that make their behaviour predictable and open to manipulation.

Other factors such as technology, taste, the weather and institutions can also influence human economic behaviour. But economists see their impact either as modest or predictable, and thus capable of being factored in to supply-and-demand models.

This neoclassical perspective is widely, although not uniformly, accepted by world political leaders. It informs and underpins policies on taxation, spending, labour market regulation, health, the environment and more.

The problem, and a key reason why economic policy often fails, is that, while Isaac Newton’s law of gravity can predict behaviour at all times anywhere on this planet, these and other supposed economic laws often fail.

Take labour markets: the Bank of England’s and the US Federal Reserve’s claims that supply and demand determine wage rates, and that wage rates determine labour supply and demand, is not based on the best evidence. Economists know this too (we’ll get to that soon).

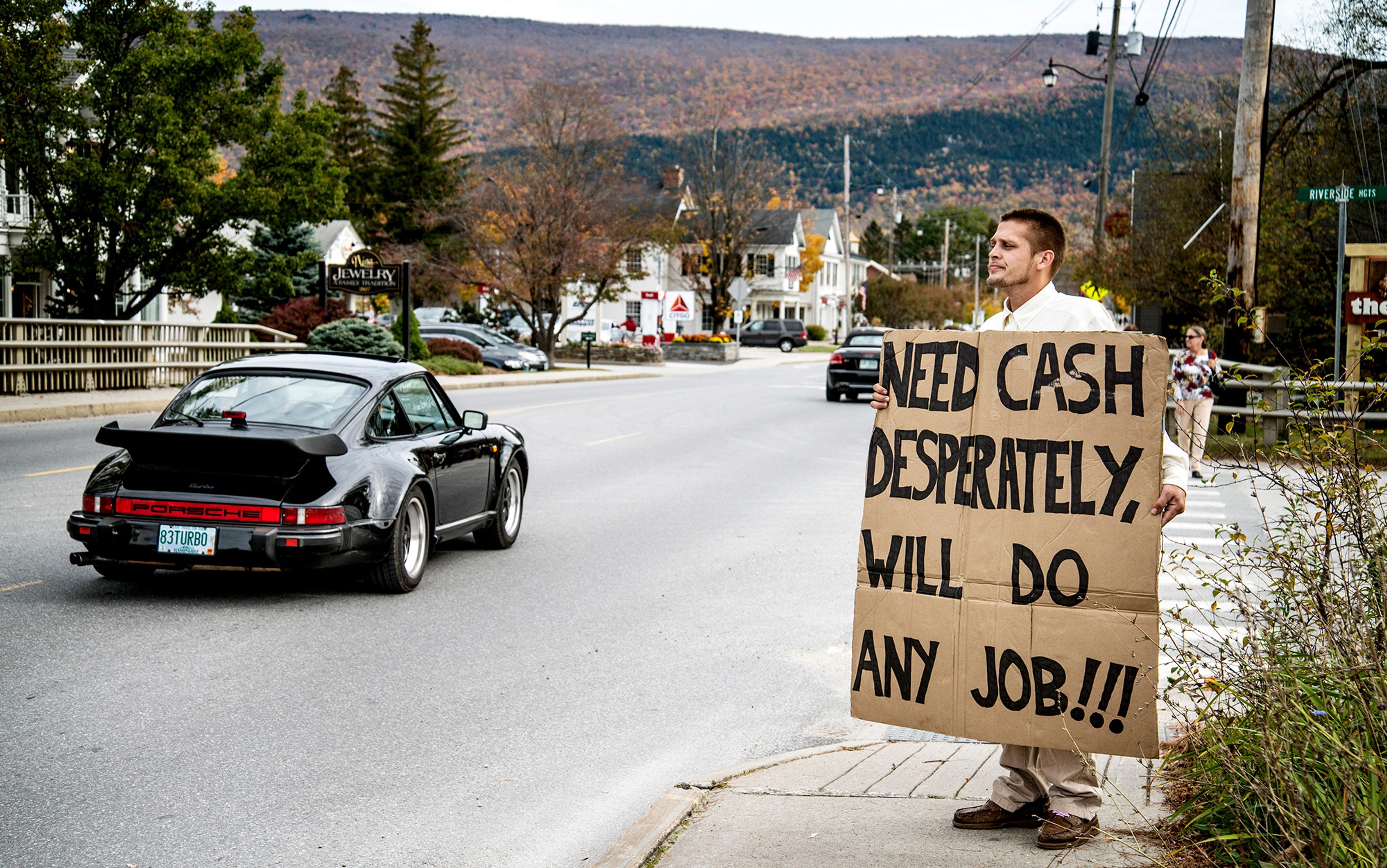

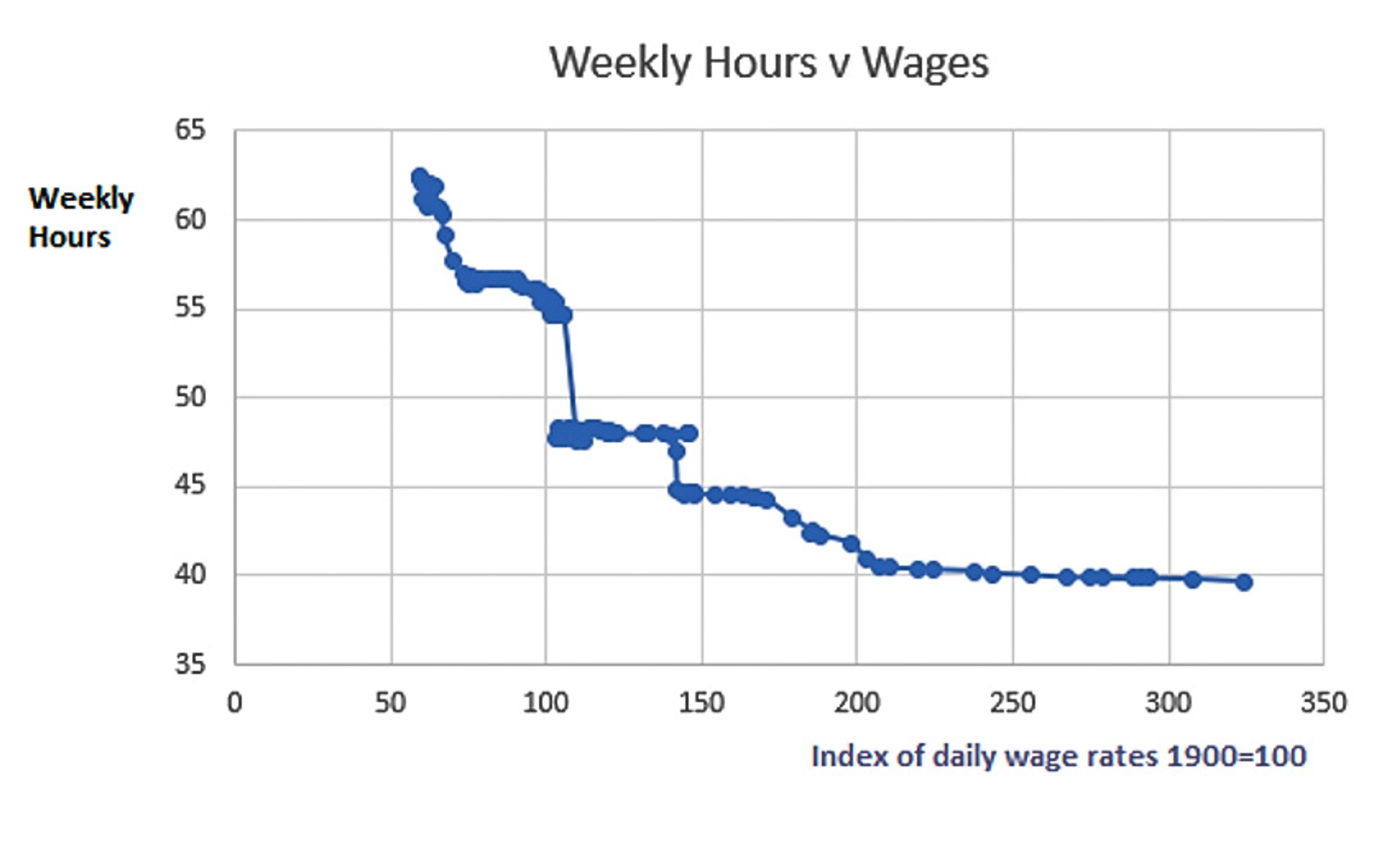

According to these supposed economics ‘laws’ (and a cheery video on the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis’s website), higher wages make people work more, and lower wages discourage people from seeking employment. In the real world, however, study after study over the decades has failed to find evidence of people working longer hours in response to higher net wages (be that through direct salary increases or tax cuts). Over the long term, the data even more strongly tell us that labour supply does not respond to wage rates. Since the mid-19th century, real wage rates have risen sharply but hours worked by individuals have fallen significantly. The labour supply curve doesn’t slope up as the supposed economic ‘laws’ dictate but downward. To put it in terms the Bank of England might understand, the labour supply curve defies gravity.

In practical terms, this means that if policymakers are trying, for example, to bring more women into the labour market, then assessing the issue via the lens of neoclassical supply-and-demand curves is unlikely to help them formulate effective solutions. Hence the failure of so many tax cuts or relaxations of employment protection rules to nudge the economies in Europe and North America towards higher employment and growth levels.

Labour supply is more a function of culture and institutions than price, and this is not a new idea. In 1978, the American Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Solow stated plainly that the neoclassical article of faith that all markets clear – which is to say, settle on a price, where demand and supply are matched – was nonsense. ‘It is plain as the nose on my face that the labour market and many markets for produced goods do not clear in any meaningful sense,’ Solow wrote.

The failure of the neoclassical framework to explain important segments of economic life hasn’t dented economists’ faith in the universal applicability of supply and demand curves. In the past 40 years or so, in fact, the trend has been to claim that such economic principles apply to more and more domains of life.

Dig even a little into the data on tobacco taxes, and one is hit by some anomalies

Up to the 1980s, for example, smoking was seen as driven by cultural factors and the product’s addictive nature – researchers even struggled to get funding for studies that sought to investigate whether price could influence consumption. But at the turn of the millennium, convinced by a raft of economic studies claiming to have established that smokers in developed countries had a clear and fixed ‘price elasticity’ with respect to tobacco, the World Health Organization declared price to be ‘the single most effective way to decrease tobacco use’. And, indeed, since 1980, real tobacco prices have increased as a result of taxes, and people are smoking less.

Yet dig even a little into the data on tobacco taxes, and one is hit by some anomalies. Firstly, economists claim that the short-term price elasticity of demand for tobacco is around 0.4, and in the long term around 1 (meaning that a 1 per cent price drop would cause a 1 per cent rise in demand). If this is accurate, it means price increases drove the vast majority, or all, of the drop in smoking that occurred over the past 40 years. Given that in surveys most people say they quit for health reasons, this seems a stretch.

Second, the fact is that the pace of price increases and smoking rates are not well correlated. For example, the real price of cigarettes in Britain was lower in 1990 than in 1965, but per-capita consumption was 20 per cent lower. What really changed, beginning in the 2000s, was the culture around smoking.

The greatest indictment of the application of neoclassical price theory to smoking is the way those people with the least financial incentive to respond to the price signal appear to have responded most strongly, while those with the strongest incentive were not impelled to react. Today, in affluent neighbourhoods in Britain smoking rates are under 10 per cent, whereas in some poor ones it’s 50 per cent. If neoclassical theory were sound, those numbers would be reversed. Around the world, this trend is replicated. That’s a fundamental breach of neoclassical economic principles.

The consequences of claiming that you’ve scientifically proven that consumption can be proportionately impacted by price manipulations is enormous. In this case, for example, faith in the theory delayed by years all the health warnings, advertising restrictions and smoking bans – all those measures that really contributed to a denormalisation of smoking.

Some economists have questioned the profession’s obsession with price. In the later years of his long life, Ronald Coase, one of the most influential members of the conservative Chicago School of Economics, began to lament how economists in the 20th century had gone down the rabbit hole of focusing on price sensitivity. He said that, rather than studying real-world wealth creation, as early economists such as Adam Smith sought to do, their successors had focused on building mathematical models of the world and probing datasets to find correlations consistent with the models. Coase didn’t consider such work to be empirical, dismissing it as ‘blackboard economics’.

In the past two decades, there’s been a turn against ‘blackboard economics’. Some younger economists have made careers out of going out and studying the world as it actually is, and deriving an economics – insights, conclusions and solutions – based on this empirical work. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of California, Berkeley have been especially prodigious in producing such economists.

Isaiah Andrews, one of these new ‘empiricists’, won the 2021 John Bates Clark Medal – the most distinguished economics prize in the United States. Andrews has worked on the problem of publication bias – whereby research that confirmed prior beliefs could have a better chance of being accepted by academic journals.

Melissa Dell, another of the new ‘empiricists’, won the 2020 Clark Medal for work that highlighted the importance of institutions in the development of economies. Her award signalled a real shift. For almost a century, the economics establishment has downplayed the role of institutions, in part because institutional factors don’t easily fit into the mathematical models that generate precise, scientific-looking results.

The 2012 Clark medallist, Amy Finkelstein, has used randomised controlled trials in healthcare to understand how people use and are impacted by insurance coverage. Her work has revealed how such markets can defy the laws of supply and demand, and shows that government intervention can help address market failures.

Markets don’t respond, as neoclassical theory claims, to the sudden hike in wage rates

Another indication that economists have at last moved to study the world as it is, the award of the 2021 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences went to three empirical economists including David Card. Few people have been at the receiving end of the economic establishment’s ire as much as Card. When Card’s work was first published, one Nobel laureate declared it ‘equivalent to a denial that there is even minimal scientific content in economics’.

Until the early 1990s, the accepted orthodoxy among liberal and conservative economists was that the minimum wage killed jobs. It simply had to, because the laws of supply and demand said the measure pushed the price of labour above the so-called ‘equilibrium wage ‘or clearing wage at which supply and demand were matched. Card and his colleague Alan Krueger conducted studies that found, in a number of cases, that meaningful increases in the minimum wage had not led to lower employment in fast-food restaurants – the type of business commonly affected by the measure. The research received a lot of publicity, and near total rejection by some of the most eminent economists, for example Gary Becker, Robert Barro and James Buchanan, who likened colleagues who accepted Card’s work to ‘camp-following whores’.

History, however, has been on Card’s side. Study after study (140 in the UK alone) has found that even large increases in the minimum wage have failed to lift unemployment. Labour and product markets don’t respond, as neoclassical theory claims, to the sudden hike in wage rates. First, employers in the US and Europe have reported that they can easily pass on minimum wage increases to customers. To ‘blackboard’ economists this makes no sense – after all, if customers were prepared to accept higher prices, the companies would have already tried to increase them. But it appears the wage hike fundamentally changes the behaviour of both employer and customer in a way for which theory cannot account. In effect, we see that consumers of services or goods do not have fixed preferences; they either do not have a price elasticity of demand, or it’s so subject to change that estimates of it are as useless as predictive tools.

Card’s Nobel Prize is a sign of economics advancing along scientific principles of learning from its previous errors. A clearer sign is the fact of governments in the UK and Germany, which had been sceptical about minimum wages, proceeded in 1999 and 2015 respectively to introduce them. Yet every introduction of a minimum wage and every above-inflationary increase is met with warnings from the economic establishment.

For example, when Germany proposed a minimum wage, the state-appointed panel of economic experts known colloquially as Germany’s ‘wise men’ called the suggestion that the measure would not kill jobs ‘a vast illusion’. More recently, the economist Larry Summers warned last year that US President Joe Biden’s proposal for a $15 minimum wage would cause employers to ‘shift away from the most vulnerable and inexperienced workers’, while Britain’s most widely cited economic forecaster, the Institute of Fiscal Studies, warns at least once a year about the potential employment effects of the UK’s typically modest minimum wage increases. Card told me that outside the field of labour economics, where scholars had studied the subject in detail, many of his fellow economists still struggled to accept the findings.

‘If you scratch the surface, you’ll find that 90 per cent of those people didn’t really change their opinion,’ he told me in 2019. Card hoped that, over time, the profession would make the appropriate intellectual adjustment as people who couldn’t drop the old ideas were replaced in faculties by people informed by significant developments in research. But don’t expect this to happen quickly.

The tripling of fuel prices had not changed Americans’ car purchasing patterns

In February 2021, the Chicago University IGM Forum asked a panel of distinguished economists if President Biden’s proposal of a federal minimum wage of $15 per hour – a level whose ratio to the average wage is in line with the levels in other countries – would lower employment for low-wage workers: 45 per cent either agreed or strongly agreed it would; only 14 per cent disagreed. This, despite a preponderance of research that has shown no meaningful disemployment effects of raising minimum wages.

If even the simple supply-and-demand curve, a staple of the orthodox neoclassical framework, fails on something so fundamental as wages and employment, why do economists cling to it? And why do policymakers keep listening to them?

Perhaps the answer to the first question lies in the second. In 2009, the then US president Barack Obama appointed Cass Sunstein as his regulation tsar, with a remit to help cut automotive emissions. Sunstein argued a carbon tax on fuel was the most efficient way to influence people’s behaviour because that’s what the neoclassical dogma says. The fact that the tripling of fuel prices in the previous decade had not fundamentally changed Americans’ car purchasing patterns apparently did not merit consideration. Neither did the fact that other regulatory measures imposed in Europe had led to a far larger increase in fuel economy with only a modest price signal via higher fuel prices.

In 2020, the UK government appointed Mark Carney – a former governor at the Bank of Canada and the Bank of England – as climate change adviser. Carney was quick to declare the problem to be essentially a mispricing of the cost of emitting carbon. Neither Sunstein nor Carney are experts in climate economics, let alone climate change. But being economists, both men believed they knew how the world worked and therefore had the toolkit to provide solutions to world’s gravest and most complex problems. Political leaders believed them. In effect, their self-confidence made them more employable.

In the past 20 years, empirical research has produced many smart and counterintuitive solutions to real economic problems. Esther Duflo, for example, a winner of the 2019 Nobel Prize in economics does what might be considered shoe-leather economics – research that involves observing real people’s behaviour in respect to meeting their material needs. However, the new empirical work in economics suffers from what some economists call the ‘transportation problem’. It might tell you how to encourage the use of efficient stoves in India or improve teaching outcomes in Kenya but the findings don’t establish universal rules about the behaviour of large populations across many markets.

That’s a problem for the economists who enjoy being the go-to experts for policymakers. Universal rules make one universally relevant. But the prevalence of bad economics in public policy isn’t just the fault of economists. Politicians and we, the public, have lapped it up.

The problem is one I call ‘free lunch thinking’. Milton Friedman popularised the saying that there was ‘no such thing as a free lunch’, yet his worldview was that, if government just stepped back – didn’t spend money solving problems, didn’t trouble itself with regulation, and left all the messy decisions around how to organise society to the ‘market’ – things would hum along and we’d all get richer magically. That sounds a lot like a free lunch.

Governments often find themselves in tight places – in the post-financial crash years, Spain and Italy faced surging unemployment and big budget deficits. One might seek to tackle unemployment with employer incentives, training programmes or by injecting demand into the economy through higher spending. Such policies cost money. So, when economists, including Miguel Ángel Fernández Ordóñez – a former governor of the Bank of Spain, the Spanish central bank – told the near-bankrupt Spanish and Italian governments they could tackle unemployment by reducing labour protections – a measure that cost nothing – the policy had a natural appeal.

Since economics wants to be seen as a science, it should act like one and take a firmer line on falsehoods

Similarly, when a government wants to reduce prices of goods or services, they could look for market-structure solutions that might build capacity or even offer subsidies, but far simpler and cheaper to just slash regulations. And when it comes to solving problems of excess consumption, such as smoking, the environment or obesity, orthodox economics offers governments a solution – sin taxes – that actually make them money rather than requiring extra spending. Taking it to its extreme, neoclassical economics paves the way for the Laffer curve, which holds that people are so responsive to price signals that tax cuts can actually increase activity so much that they lift exchequer receipts. It seems to give governments the ability to raise more money by taxing citizens less!

Neoclassical economics offers economists a palate of answers for almost any problem, and many of those answers are naturally appealing to political leaders and voters. The problem is they are often obviously wrong. This presents economists with perverse incentives. And hence a need to have a laser focus on truth.

Paul Romer, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for economics in 2018, has earned a name for himself as a troublemaker in recent years for criticising the economics profession’s problem with truth. He has taken the unusual action of accusing distinguished peers of being frauds and of using mathematical abstractions and other obfuscations to deliberately hide flaws in their research. Romer’s argument is that, since economics wants to be seen as a science, it should act like one and take a firmer line on falsehoods. ‘A little bit of bad intent can manipulate the consensus. And this is why we should kick people out when you find they are not reliable,’ Romer told me over a coffee in Greenwich Village a couple of years ago.

Flippancy about facts is a hallmark of economics. When Card’s research about the minimum wage made headlines, the Nobel Laureate Gary Becker claimed that a vast body of research disproved Card’s work. However, this is not true. Indeed, the academic review of published work on the minimum wage, which opponents of the minimum wage use most frequently in defence of their position, had actually said it couldn’t find strong evidence that the minimum wage caused unemployment in low-skilled adult workers.

Today, economists still feel comfortable assuming that the facts support them when they blindly assert the economic orthodoxy holds to any given situation. Take the Bank of England’s claim on its website that the laws of supply and demand explain the vast increase in footballers’ wages in the recent past. The law predicts that if consumers want more of a good or service, prices should rise. Yet the number of players demanded by clubs in Britain’s Premiership has dropped in recent decades due to the reduction in the number of teams from 22 to 20 and the introduction of squad size limits that cut the number of players to 25 from at times over 50.

The market for Premiership footballers is a poor illustration of the laws of supply and demand in action. But it provides a perfect example of how economists have so much faith in the rules that they don’t study a market before asserting it proves their theory of how markets work.

The assertion that one’s theory will apply in situations one hasn’t studied and where there is actually strong evidence – if you cared to look at it – that the situation doesn’t conform to the theory reflects a total abandonment of scientific process and the expression of pure dogma.

Social sciences like economics face certain handicaps compared with the physical sciences where one can easily isolate the phenomena one wishes to observe and experiments can be repeated without too much difficulty. Yet there is no reason why adhering to the scientific method of basing conclusions and world views on observable facts should be more challenging in economics than in physics. Except that the incentives are against it. If you have a dogmatic neoclassical view of how the world works, you’ll always have a solution to the economic problem of the day. And, therefore, you will have influence. Looking at the facts first may well mean having to say ‘I don’t know.’

If economics is to become more useful, its practitioners have a lot to learn. But in terms of impact, more may be gained if they focus on unlearning the pervasive myths they advance to policymakers.

As Romer told me: ‘You can’t overestimate the way that “theory beats fact” has infected economics.’