What is a ‘natural’ food product? One common suggestion is that ‘natural’ things are not made of chemicals. But the whole biological world is chemicals! Another suggestion: natural products are not genetically modified (that is, a GMO). Alas, that won’t work either. While GMO designers do mix and match genes artificially, the bacteria at work in you and your food do the same thing and have always done so. How about not made in a lab? No, the Vitamin C from a lab is the same chemical as the Vitamin C from an orange.

So it isn’t easy to say what a natural product comes to. Understandably, many commentators have thrown up their hands in despair. Even the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has given up on enshrining a formal definition of ‘natural’. But giving up is an overreaction. Outside the clean world of mathematics, nearly all concepts are in want of clarification, and natural is a useful enough notion for us to attempt to clarify. In spite of its trendy appearance, the core idea behind ‘natural’ has been around at least since Aristotle.

An Aristotelian account comes to this: foods similar to the foods that our ancestors ate in their natural environments are the foods that we are designed to flourish on. When we deviate from design, we run risks. Eating naturally is eating what we’ve been designed to eat, just like a car that is designed to run on gasoline, not diesel or oil. The question is: who or what designed us for the natural foods that fuel us? Neither Aristotle nor most of those deeply beholden to him in the succeeding ages could answer detailed questions about that, from a scientific standpoint. It took Charles Darwin in the 19th century to introduce those answers.

Darwin would say that our ancestors, who managed to make good use of the foods available in their environment, survived to pass on their genes to us. They were naturally ‘selected’ for preservation. As their descendants, we inherit their body type, which does well eating those same types of foods. Not everyone around at the same time as our ancestors had bodies like theirs, of course. Those who found the available food indigestible were poorly nourished, so they couldn’t flourish. They couldn’t pass on their own body type to a line of descendants who would last until today for anyone to inherit that body type. Gradually, selection designed bodies to make good use of the natural foods available.

For example, we’re designed for fruit, because that’s one of the primary foods our ancestors enjoyed. A long process of evolutionary selection designed our ancestors, even before there were humans, to derive benefits from the fruits they ate. A substantial portion of terrestrial animals have eaten fruit, so our bodies (and those of turtles and mice, say) are designed by evolution to flourish from fruit’s nutritional potential. In fact, just as we are naturally designed to eat fruit, the fruit is naturally designed by its plant source to benefit us. By feeding us with its berries, a blackberry bush or a banana tree uses us to collect and spread its seeds – with a little fertiliser. (Yes, technically bananas are berries.) These seeds have done well: they have passed on their genes for packing seeds in a nutritious package for animals like us to eat and then to replant in another nutritious package to help the seeds get off to a good start. It benefits the plant to keep us around, spreading its seeds for many seasons.

Our systems are less-well designed to metabolise fruit juice with its concentrated sugar load than the fruit itself. Our ancestors didn’t juice their fruit – that would have been a lot of extra work for no gain. So evolution designed you to flourish not on the juice but on the fruit. Of course, juice is similar enough that your body can make some use of it but it’s not as good as the fruit because your body is best equipped to profit from the fruit’s combination of nutrients taken together.

Today, orange juice is associated with a complete breakfast but only because of new economic developments. A century ago, orange juice came from your orange. Market conditions have recently motivated economic powers to reshape our thinking since there are only so many whole oranges the country can eat. Many more oranges can be sold and consumed in the form of juice concentrate. Shipping and preserving got easier too. When you juice a fruit, you remove a lot of things that help us to make use of the food, like the fibre and phytonutrients. Your body can’t process the sugars as well if the rest of the orange is missing. Evolution has not given us the equipment to deal well with just isolated juice. The human body takes longer than the market to adapt to new conditions.

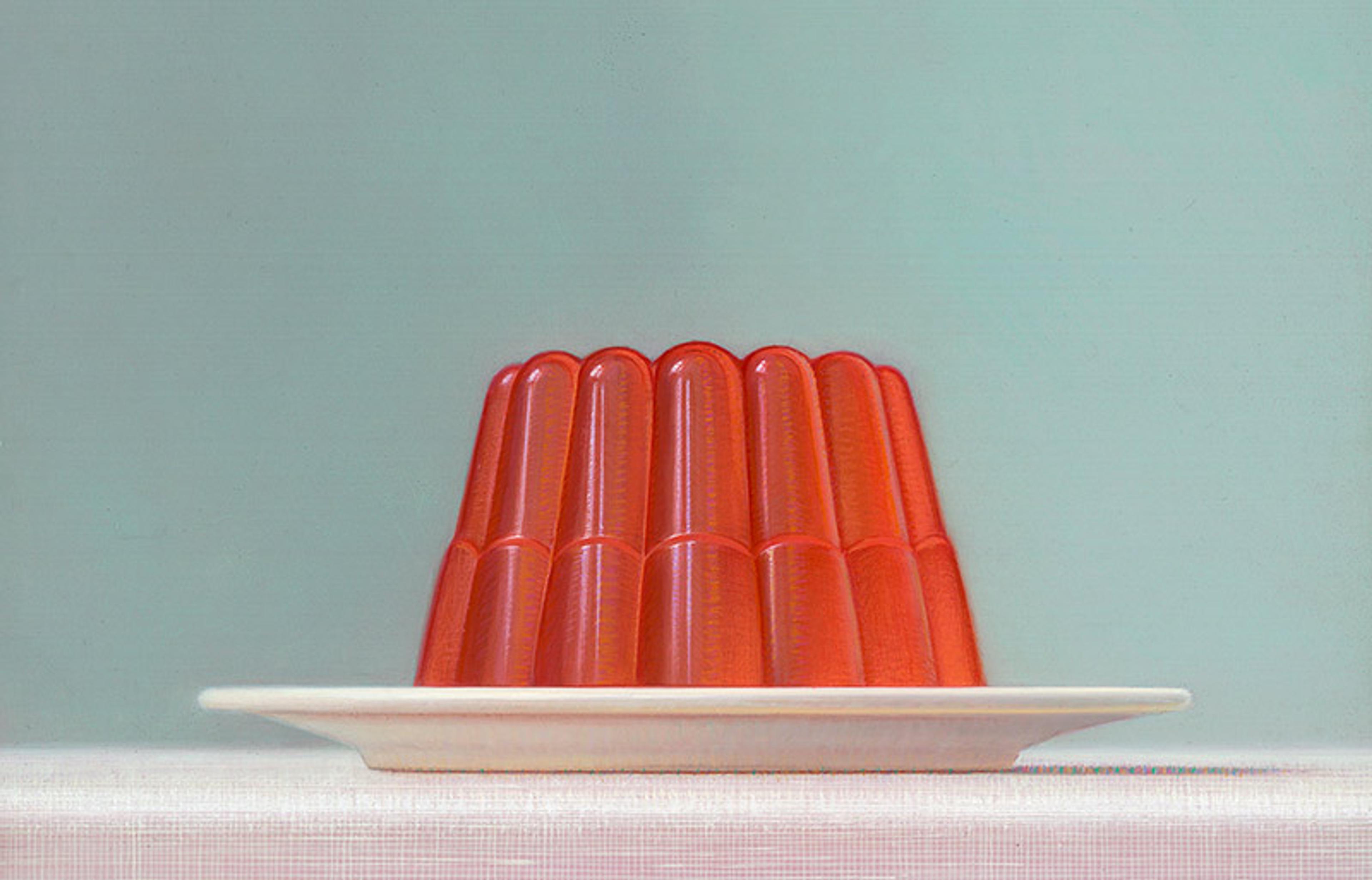

Still less is our body designed for sugars alone, can might be isolated from the fruit just as the juice can. The sugars might then be dumped in a so-called ‘fruit punch’ or ‘juice drink’ by the spoonful, perhaps with Vitamin C which is also isolated from the fruit. ‘Fruit punch’ should be regarded as unnatural for us because unlike pure fruit juice, fruit punch, with its low fruit content (perhaps 5 per cent juice) and high added-sugar content, is too remote from what our bodies have been designed to deal with for us to benefit from it. Fruit-flavoured soda, which has no fruit juice at all, is even worse. Forget about whether the sugar is derived from a natural source such as fruit. Forget about whether there are so-called ‘artificial’ ingredients to flavour the soda, like aspartame and saccharin, which are lab inventions. Too much sugar isolated from the fruit is itself a problem that alone spoils any reasonable claim to a beverage’s naturalness. A crucial point is that naturalness comes in degrees, and ‘fruit punch’, not to mention soda, are too low on the scale to be worth calling natural, because we’re so ill-equipped by evolution to benefit from them.

Critics of natural living sometimes stress that all this focus on our ancestral, natural environment is only sentimental yearning for a past paradise that never was. Mythical associations evoked by blue corn chips from the Garden of Eatin’ might sell tortilla chips but they have little basis in reality. Science cannot speak to any pristine natural paradise in which humans ever flourished. Nature has always been ‘red in tooth and claw’, as the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson put it in 1849. There was never a time before the snake struck at our heel with poison as effective as any we’ve concocted artificially since. So perhaps there’s nothing desirable about returning to ‘natural’ living?

Besides, a related objection goes, we humans and all we do have always been part of our own natural surroundings; we can’t understand our natural environment as something isolated from ourselves and our creations. So how can we recognise any difference between natural and artificial? After all, if the mating dance of a bird or the hive of a bee is a naturally evolved phenomenon, then so are human behaviours and human artefacts, including those we call ‘unnatural’. All of this trivialises a ‘natural’ lifestyle. A club with everyone as a member isn’t a very interesting club: so goes a second worry.

Satisfactory answers to these worries come with help from philosophers of language, such as the late David Lewis. Lewis emphasised the interesting ways that context can direct you to what you’re talking about. If I open the fridge and tell you there’s no beer, you won’t then object that you just saw some at the supermarket. I’ve set a context by searching through the fridge. But if I stand by a bare patch on the supermarket shelves that normally stock beer, the very same sentence works to communicate something different: whatever might be in my fridge, the supermarket is out of beer.

The relevant context for ‘natural’, too, varies. From the perspective of the language of science, natural often means anything physical. Quarks or black holes, Teflon or saccharin, these are the ‘natural’ subject matter of the ‘natural’ sciences, traditionally contrasted with, say, theology. What qualifies as ‘natural’ for marketers and consumers of ‘natural’ products that we eat, drink or use is more discriminating than what counts as the ‘natural’ subject matter of the natural sciences. Products for natural living concern what contributes by design to our flourishing. That would not include everything from our natural environments, which could be hostile as well as supportive for us.

You’re probably better off with artificial diet soda than with naturally honey-sweetened soda

Finding the roots of ‘natural’ in our past might suggest, to some, the so-called ‘paleo-diet’. The problem with this diet is that it is too narrowly focused on the hunter-gatherer stage in human evolutionary development, before agriculture developed some 10,000 years ago. Evolution has continued to shape our design since then. For example, dairy farming in Scandinavia some 10,000 years ago has designed Scandinavian people to be highly lactose tolerant. There are isolated African communities with a similar heritage and a similar inheritance. Most Asians, on the other hand, become lactose intolerant as adults, not having had a history of dairy. Our bodies testify to evolution’s quick handiwork. They also testify to evolution’s long-term storage, so we’re designed to flourish from foods such as those that would pre-date any human environment. Europeans could readily enjoy tomatoes, potatoes and corn, which they had never tasted before they found the Native Americans’ crops. In their turn, Native Americans enjoyed apples, oranges and European grains, all of which were new. These foods are similar enough to foods that the human and pre-human ancestors of all modern humans ate that people were able to handle the new variations right away. This explains why even dogs – natural carnivores – show substantial benefits from these very same fruits introduced to them for controlled studies. Dogs share with us substantial overlap in design – as do the fruiting plants that serve us both well. Evolution saves its work.

Does natural amount to ‘healthy’? In fact, some foods we’re designed to benefit from don’t help us stay healthy. There are many reasons for this. One reason is today’s lifestyle, which might throw off our natural reception of foods for which we’re designed. Potatoes are natural but according to the School of Public Health at Harvard University, they’re ‘really unhealthy’, just like ‘sugary drinks’. This is because your ancestors earned the benefit from them, with a more completely natural lifestyle. Regular consumption of potatoes ‘may be okay for people who dig their own’, according to Walter Willett, professor of epidemiology and nutrition at Harvard. ‘But today, few Americans get the amount of physical activity our ancestors did 80 years ago, and that means our metabolism responds poorly to high amounts of starch.’ In our natural state, we had to dig our tubers. There were no supermarkets.

That is why even natural carb sources such as potatoes (also honey and maple syrup) may be less healthy for most people today than ‘artificial’ nearly-zero-calorie sweeteners in diet sodas, such as aspartame or saccharin. Aspartame and saccharin are human-created chemicals that artificially replace real carbs, which are calorie-rich. (Regarding the worry that artificial sweeteners put you at risk of cancer, the chances are actually vanishingly small. Your risk of disease from carb overload from foods such as sugared sodas, on the other hand, is astonishingly high, whether the carbs are natural, like honey, or unnatural, like table sugar.) So given our unnaturally high levels of calories, and given our unnaturally low levels of exercise, you may well minimise risks to your health by choosing artificial diet soda rather than naturally honey-sweetened soda because the diet soda doesn’t add still more calories to your diet. Too many calories is a major cause of death today: many people you know will die of diabetes or heart trouble, leading causes of which include our unnaturally calorie-rich diets.

So ‘natural’ isn’t the same as ‘healthy’ – but is it instead the same as ‘unprocessed’? After all, the obstacle to counting table sugar as natural is that processing has extracted the sugar from the rest of what is in its plant source. Perhaps natural is superfluous? Can’t we just say ‘whole foods’? No.

Skim milk is not a whole food: the cream, which rises to the top of natural milk, has been skimmed off. But skim milk might be natural for you. Your ancestors might have drunk it, saving the fat for butter and cheese. Green grass from the wheat plant, on the other hand, is whole, but there’s reason to doubt that it’s natural for you because it isn’t clear that you’re designed with the right digestive system. Cows are another story. Some plants design whole foods for foragers other than you. Many red and white berries should be left to birds, excellent seed dispersers who eat a broader span of berries than us. Not all foods natural to cows or birds are natural to us.

Innovations have not done the body well. Too much has changed too radically

Natural isn’t the same as whole or healthful. Even so, natural should be associated with these concepts. Unnatural foods tend to be the same foods as so-called ‘processed’ or ‘refined’ or un-whole foods, as well as unhealthy foods. That’s because evolution – fast as it is – can’t redesign the human body in less than a century and a half to make good use of the radically new refined diet introduced by the Industrial Revolution. The new diet is comprised largely of refined flour and sugar and other foods of unprecedented caloric density. Milled ‘white’ flour has been shorn from the other parts of the grain, the germ and bran, just as purified sugar has been shorn from other parts of the plant source. These foods and foods like them, which now make up a significant part of US consumers’ caloric intake, often ‘resemble natural foods, but actually represent a radically new creation’, as the US physician David Ludwig writes – tacitly presupposing, by the way, the sort of context we’re looking for. Innovations have not done the body well. Too much has changed too radically. That’s why natural, whole and healthful is often the same in practice.

The components of a natural life work best together. Living naturally means getting out for a walk through a wooded path, as growing numbers of health providers are advising, following studies suggesting improved function from all we take in by way of the soil, air, lighting and so on. Perhaps this shouldn’t be surprising in view of some 50,000 generations through which humans evolved as hunter-gatherers, followed by 1 per cent of that time as agricultural workers, and then an evolutionary blink of an eye during which our species has been indoors, stationary.

Living naturally moves us to conserve and restore the environment, so that a daily walk along a wooded path is even an option for you in a world where, again for the first time, most people live in urban settings. Conservation also means reducing our consumption of all products, even natural ones. Our environment meets us in the air we breathe and the water we drink. Just buying products at all, whether those products are natural or not, contributes to an unnatural environment in the big picture, because of the pollution to our air and water, from manufacturing.

Pause to reflect on the packaging alone for a natural product: paper, plastic, metals, inks, glues. Add up all the products you bring home in a week. Many purchases on the part of many consumers have unnaturally altered the air and the water in seas and oceans, which are now vastly different in chemical makeup from when they immersed our ancestors. The distinguished biologist Paul Ehrlich at Stanford University writes: ‘All living things – us included – have been plunged into a sickening poisonous stew’, comprised of manufacturing-byproducts from materials we buy and toss away every day without a second thought. Thinking natural can encourage us to wiser reflection.