Since the dawn of recorded law, Western societies have recognised that some people shouldn’t be held liable for their acts because they are non compos mentis – not in their right mind. This exemption from criminal sanctions was seen as an act of mercy required by basic morality: it was immoral to exact vengeance against a person who didn’t know that his behaviour was wrong. This principle was well-established in English common law, and from there into the law of the United States. The question has always been ‘the kind and degree of insanity that would excuse its victim from punishment for an act which if done by a sane person would bring upon him the sanctions of the law’, as put in the House of Lords in 1843.

As a former forensic psychologist and prosecuting attorney in New York, I’ve had a front-row seat to the courts’ struggles to define the parameters of this defence of insanity. Until the 20th century, little was known about mental illness. Judging whether a person was deranged – seriously mentally ill and irrational – was seen as a matter for common knowledge. It was a case of ‘I know it when I see it,’ to echo the later words of the US judge Potter Stewart, who in 1964 was struggling to formulate a definition of hardcore pornography that would differentiate it from constitutionally protected speech.

The courts tried to codify and standardise the construct of criminal insanity. By the 18th century, the commonly applied legal test in England was that a man should be found not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI) if he is ‘totally deprived of his understanding and memory, and doth not know what he is doing, no more than an infant, than a brute, or a wild beast, such a one is never the object of punishment’. Animals ‘know’ what they are doing, of course, but they don’t know the moral dimension of it. The reasoning was that a person in the grips of mental illness should not be punished for illegal acts, if he or she doesn’t know that those acts are ‘wrong’, meaning against the laws of God as well as man, immoral as well as illegal.

The public demands, and the courts provide, a forum for identifying and punishing the wicked; in Western philosophical tradition, people are assumed to have free will, and therefore to be able to choose to do either good or evil. If they choose evil, it is right to punish them. The severely mentally ill were excused from punishment because, as St Augustine reasoned: ‘All men have freedom but it is restrained in children, in fools, and in the witless who do not have reason whereby they can choose the good from the evil.’

Courts continued to waiver between holding any person guilty who ‘knew’ what he was doing, and holding to account only those who were morally aware of the wrongness of their action. The problem with this formula is that we tend to measure the wickedness of an actor by the degree of outrage we feel at the act. So, though the original spirit and intent of the insanity defence – to not punish those who, through no fault of their own, were driven by mental illness to commit illegal and immoral acts – remained clear, its application was inconsistent.

In the American colonies, courts swung between a good-versus-evil approach to criminal guilt, and a focus on the mental derangement of a defendant. In 1639, Dorothy Talbye was hanged in the Massachusetts Bay Colony for breaking the neck of her three-year-old daughter, named Difficult. Governor Winthrop tells us that Talbye ‘was so possessed with Satan, that he persuaded her (by his delusions, which she listened to as revelations from God) to break the neck of her own child’. The Puritans saw what was almost surely a severe case of postpartum depression as a choice to listen to the devil and do evil.

But contrast this with the case of Mercy Brown in 1691 in Connecticut. She had a long history, well-known to the townsfolk, of being ‘crazed and distracted’, and when she murdered her child she was held by the jury to have been not in control of her own mental faculties. Though she was kept in custody ‘for preventing her doing the like or other mischief for the future’, she was spared the death penalty required for those convicted of murder.

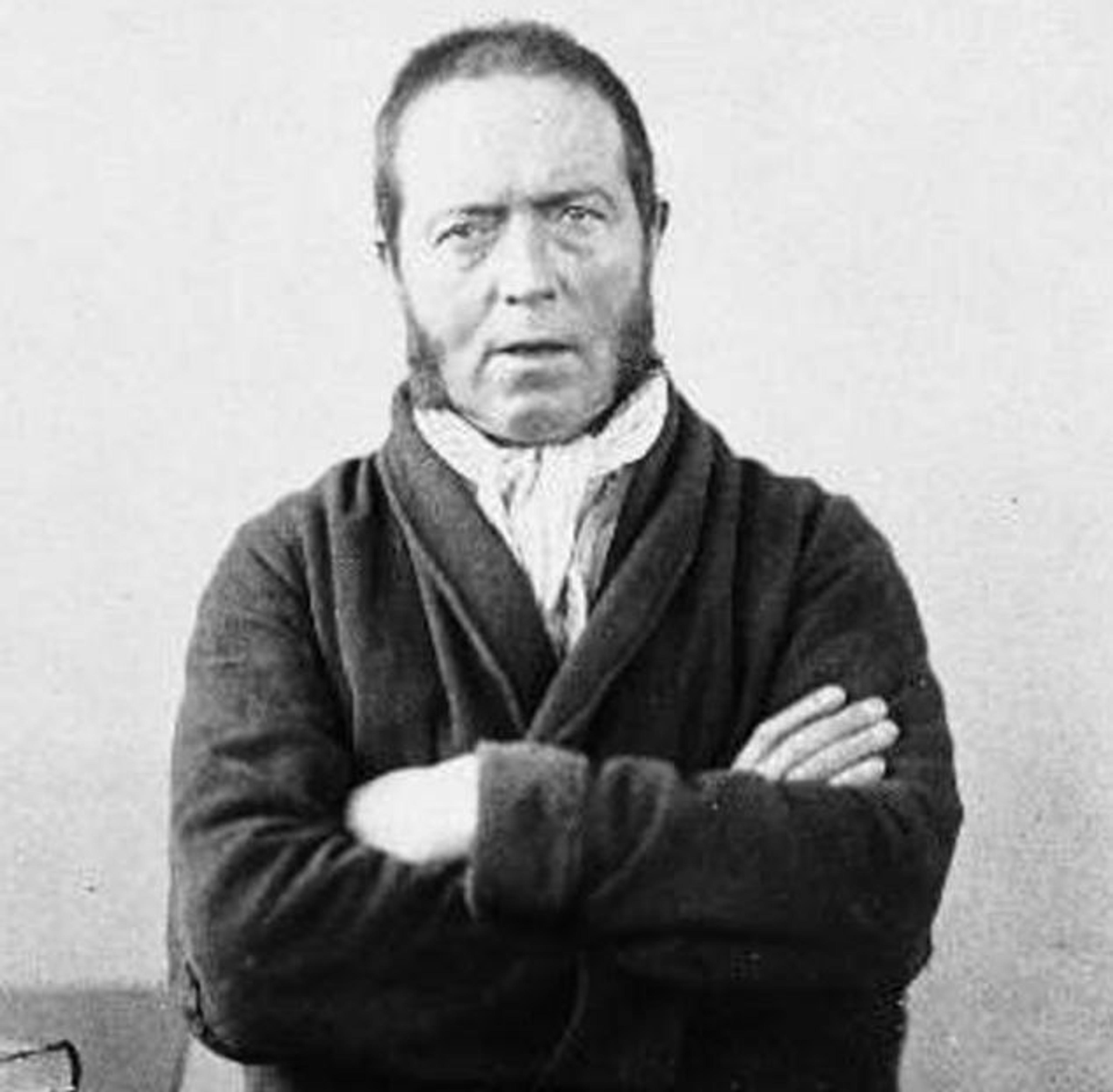

Back in England, when Edward Oxford, an unemployed waiter with a history of mental disturbance, attempted to assassinate Queen Victoria in 1840 and pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity, the court ruled that ‘if some controlling disease was … the acting power within him which he could not resist, then he will not be responsible’. Similarly, when an impoverished, delusional, Scottish woodcutter named Daniel M’Naghten tried to assassinate the prime minister in 1843, killing instead the minister’s secretary, the judge instructed the jury at his murder trial that:

the question to be determined is, whether at the time the act in question was committed, the prisoner had or had not the use of his understanding, so as to know that he was doing a wrong or wicked act. If the jurors should be of opinion that the prisoner was not sensible, at the time he committed it, that he was violating the laws both of God and man, then he would be entitled to a verdict in his favour …

M’Naghten was acquitted, but this case was a hinge point; Queen Victoria was incensed by M’Naghten’s acquittal. In a letter to the prime minister William Ewart Gladstone in 1882, she wrote:

Punishment deters not only sane men but also eccentric men, whose supposed involuntary acts are really produced by a diseased brain capable of being acted upon by external influence. A knowledge that they would be protected by an acquittal on the grounds of insanity will encourage these men to commit desperate acts, while on the other hand certainty that they will not escape punishment will terrify them into a peaceful attitude towards others.

From the mental health standpoint, this is an unsound position; I’ve yet to discover a psychotic person in the grips of a powerful delusion who can be dissuaded from acting upon it by rational argument or threats of punishment; there is no moral dimension to a delusion. But Queen Victoria’s thesis illustrates what the Canadian lawyer Ciara Toole (now Mackay) in 2012 called the ‘collision between fundamental concepts of moral and legal culpability and new scientific understandings of mental function and disease’.

‘This formula … is based upon a conception of insanity that is a myth’

At Queen Victoria’s behest, the House of Lords in 1843 convened a panel of judges to narrow the legal definition of insanity. Known as the M’Naghten Rule, a person was to be found NGRI in the future only if he or she

was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or, if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong.

As applied in the US, this has become a merely cognitive test, without any formal moral dimension: did the defendant know what she was doing when she committed the act, and is she generally able to distinguish right from wrong (without reference to the specific act)?

By way of illustration, under the M’Naghten Rule, if a woman shoots a man, knowing she is shooting a person and that shooting people is illegal, she will be considered sane and guilty, even if she suffers from a psychotic delusion that the man is carrying a deadly virus from Mars that will kill all mankind unless she can kill him first. She ‘knows’ killing men is wrong legally, so she is guilty, even if she thought her specific act was morally right. As the American neurologist Morton Prince wrote in 1912: ‘The inadequacy of this formula or test will be seen when it is remarked that it is based upon a conception of insanity that is a myth – a condition of mind that never exists.’

The M’Naghten test was adopted by almost all jurisdictions in the US. In 1881, when Charles Guiteau shot the president James Garfield, the prosecutor at trial equated insanity with a lack of intelligence. In his closing argument, he said:

[I]t is hard, it is very hard to conceive of the individual with any degree of intelligence at all, incapable of comprehending that the head of a great constitutional republic is not to be shot down like a dog.

Guiteau, who was clearly not of sound mind but had satisfactory intelligence, was convicted and hanged.

The courts have been relatively unresponsive to medical expertise, even as the fields of psychiatry and psychology have added to our understanding of mental illness. The 16th-century Dutch physician Johann Weyer sought to challenge the Saxon Code of 1572 on its treatment of insanity, complaining that it didn’t reflect the realities of mental illness. The judge retorted: ‘Weyer is not a lawyer, but a physician – consequently, his view on the relationship between mental disease and transgressions of the written law are of no moment.’ Nearly 400 years later, in 1950, the schism between legal definitions of insanity and the psychiatric realities of mental illness continued; the US Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter noted ‘the pathological processes which give rise to the conflict between so-called legal and medical insanity’. In the ensuing almost 40 years, Toole writes, the ‘legal definition of exculpatory mental disease in the context of criminal liability has remained largely static, sheltered from the immediate influence of medical theory and advancements’.

The current legal definition of insanity has no psychiatric correlate; it is a pure creature of law, owing nothing to psychiatry and the sciences of brain and behaviour. As the psychiatrist Gregory Zilboorg wrote in Mind, Medicine and Man (1943):

Except for totally deteriorated, drooling, hopeless psychotics of long standing, and congenital idiots – who seldom commit murder or have the opportunity to commit murder – the great majority and perhaps all murderers know what they are doing, the nature and quality of their act, and the consequences thereof, and they are therefore legally sane, regardless of the opinion of any psychiatrist.

The lack of a psychiatric correlate makes it look like psychiatrists and psychologists are unreliable or that mental illness is purely subjective; the fact is, mental health experts often can’t agree on whether a defendant fits into the legal definition of insanity, even though they agree about the defendant’s diagnosis and degree of psychiatric impairment. As the forensic psychiatrist Thomas Gutheil at Harvard Medical School said in 1998: ‘Psychiatric testimony is about meeting the legal criteria for an insanity-related defence, not about mental illness.’ In ‘On Responsibility’ (1996), the federal judge Richard Lowell Nygaard wrote:

With contemporary psychiatric and psychological data, the legitimate experts, who must testify about mental conditions, are unable to make accurate and scientific determinations fit into the rigid legal definitions the law imposes … Trials in which a jury must decide upon the accused’s guilt based upon the contradictory testimony of experts result in ‘battles of experts’ that virtually assure arbitrary outcomes.

We tend to measure the wickedness of an actor by our degree of outrage over the act

When testifying as a forensic psychologist, I’ve often felt torn between testimony that is legally right and testimony that feels morally right. But perhaps it doesn’t matter: Norman Finkel’s observations on ‘Insanity Defenses’ (1985) remain true today:

Jurors may often disregard or reconstrue both the expert testimony and the instructions to the jury, choosing instead to follow their own, intuitive understanding or common sense notion of what is and is not insane.

The problem with this formula is that we tend to measure the wickedness of an actor by our degree of outrage over the act. When the act is horrific, we impute evil to the actor, without much consideration for his mental state. This allows room for bias, moral condemnation, and the impulse for retribution to enter the process. In the case of Yoselyn Ortega, the nanny who in 2012 stabbed to death the two children in her care, the jury in New York rejected her plea of NGRI, in spite of evidence of a serious psychiatric disorder. The judge called her ‘pure evil’, and the children’s father said ‘she should live and rot and die in a concrete and metal cage’. Her act was certainly of the most evil kind, but was she? Did she do the thing with knowledge that it was evil, with evil intent, and with the capacity to control her behaviour?

If jurors don’t identify with the defendant, perhaps because of ethnic, racial, gender or demographic (status) differences, if they fear the defendant (perhaps owing to the same biases), and if the criminal act is one that particularly shocks their conscience, acquittal is unlikely, no matter how mentally ill, delusional or irrational the defendant was at the time of commission of the crime.

I believe this accounts in part for defence attorneys’ hesitation to raise an insanity defence. Approximately 15 per cent of those incarcerated in US prisons have serious mental health disorders. But only 1 per cent of all felony defendants plead not guilty by reason of insanity, and only a quarter of those are found NGRI, in spite of strong psychiatric evidence. As Nygaard said, the legal definition of insanity is in such ‘nebulous and often psychologically meaningless terms’, it results in ‘almost wholly arbitrary decision[s] as to who knows “right” from “wrong”’. These numbers suggest that, to paraphrase Shakespeare, the insanity defence is more honoured in its breach than in its observance.

Studies have consistently found racial and economic disparities in the US criminal justice system, and the insanity defence is not immune from them. Indigent defendants are entitled to counsel, but they are not guaranteed attorneys with sufficient experience, reasonable caseloads or adequate resources to research and prepare their cases. Public defenders are generally overworked and underfunded. In 2013, the report of the Sentencing Project to the UN Human Rights Committee concluded that: ‘the United States in effect operates two distinct criminal justice systems; one for wealthy people and another for poor people and minorities.’

Here we run into the other factors that account for black people in the US being disproportionally arrested, charged, convicted and harshly sentenced, compared with white people. As the legal scholar Hava Villaverde wrote in 1995: ‘overall arrest rates for blacks were four times that of whites, and the arrest rates for murder, in particular, were 10 times that of whites’. Furthermore, as the criminologist Alfred Blumstein found in 1982: ‘black males in their 20s suffer an incarceration rate that is at least 25 times that of the total population’. A disproportionate number of black defendants are represented by public defenders, rather than by private attorneys. The position of the US nonprofit Mental Health America is that:

The insanity defence is under-utilised due to the general failure to fully fund criminal defence lawyers for persons who are indigent. Over-worked and under-paid public defenders may not have the time, or sometimes the training, which would lead them to fully investigate whether an insanity defence is warranted and may lack the resources to retain a mental health expert whose opinion is essential to support the defence.

This squares with my own observations: it’s quicker, and often more certain, to use psychiatric evidence to plea-bargain with the prosecutor before trial, in hopes of a lesser sentence. Undoubtedly, many defendants who meet the legal definition of insanity never go to trial or raise this defence; rather than risk such a low-odds defence to a serious charge, they plead guilty to some reduced charge – often one that exposes a defendant to a possible life sentence, or even the death penalty.

We should have the issue of insanity decided by a panel of three judges rather than by a jury

But how comfortable should we be when a person who is not morally culpable due to mental illness pleads guilty, instead of being found NGRI? The conviction subjects defendants to moral condemnation for acts of which they had no rational comprehension. Secondly, an NGRI acquittal, unlike a prison sentence, is supposed to provide ‘such individual treatment as will give each of them a realistic opportunity to be cured or to improve his or her mental condition’, as the attorney-physician Morton Birnbaum first argued in 1960. Thirdly, a person confined pursuant to an NGRI finding is supposed to be freed when no longer mentally ill and a danger to others; furthermore, it is unconstitutional for a state to confine such an individual for longer than if he had been found guilty of the crime. Periods of confinement after a finding of NGRI should therefore generally be shorter than the sentence for conviction of a crime.

What can be done to rehabilitate the insanity defence? There are the obvious process fixes: all defendants should have equal access to legitimate defences, and this means providing adequate funding for public defender services, smaller caseloads, and more money for investigation and mental health evaluations. There should be clear competency standards for attorneys raising an insanity defence, just as there are for attorneys in cases involving the death penalty. We should establish higher standards for those who perform forensic psychiatric evaluations. Structurally, we should have the issue of insanity decided by a panel of three judges rather than by a jury. This would likely reduce the effects of both bias and emotion, and temper the desire for retribution regardless of mental state.

But the most profound change must be in the definition of insanity itself. It must be brought into conformance with psychiatric realities, and back to its moral and ethical roots. Those whose criminal act is the product of an irrational delusion or compulsion brought about by mental illness, rather than by bad character or the desire for personal gain, should not be the object of conviction and retribution.

In sum, it offends the conscience, and erodes the moral basis of the criminal justice system, to convict and punish those whose mental illness prevented them from knowing that what they were doing was morally wrong, all the more so when those convicted are disproportionately impoverished and people of colour.