This year marks the 50th anniversary of two legendary space epics, 2001: A Space Odyssey and Barbarella. Both hit cinema screens in 1968, with Stanley Kubrick’s vision of the cosmic-industrial sublime in April and Roger Vadim’s psychedelic sex-fuelled dreamscape in October. 2001 is often hailed as one of the greatest films of all time, deemed ‘culturally significant’ by the US Library of Congress. Barbarella, meanwhile, is often relegated to the realm of kitsch, its admixture of space-kittenish, Fellini-esque aesthetics and general aura of winking fun regarded as too light and absurd to be taken seriously. I want to argue for a different assessment by proposing that, behind its ironic façade, Barbarella presents a more radical vision of space.

During the past year, the half-centenary of 2001 has unleashed an outpouring of adulation. In a special celebration at the Cannes Film Festival this May, Christopher Nolan, the director of Interstellar (2014), presented a new 70 mm print struck from the ‘original camera negative’ – a sort of cinematic laying on of hands. ‘It is an honour’ for Cannes to present ‘one of the most extraordinary films in the history of cinema’ to a new generation, the festival’s director Thierry Frémaux told The Hollywood Reporter. And then in August, the scholarly text Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece by Michael Benson hit bookstores worldwide, receiving glowing reviews and major critical attention.

Benson’s book begins with a list of more than 40 ‘major characters’ who contributed to the film, onscreen and off. The only woman in this honourable roll-call is Kubrick’s wife, Christiane. Although we catch a brief glimpse in the film of one of the astronaut’s daughters on the far end of a video call, and a female Soviet scientist is momentarily engaged in an early scene, the only other women on screen are a flock of hostesses and receptionists on the space-station, pattering around in swinging 1960s outfits and perky vinyl booties, while Strauss’s The Blue Danube soars on the soundtrack. Once the main story gets underway, with Dave Bowman (played by Keir Dullea) piloting the Discovery One spacecraft toward Jupiter and his fabled encounter with the ‘Star Gate’, it’s men all the way. Even the murderous computer HAL is male.

Benson is a friend, who has written a fine and elegant book but, as his story highlights, space fiction, along with actual space science, has been largely dominated by men. That is changing – as the deeply engaging female leads in such films as the Alien series (1979-), Arrival (2016) and Annihilation (2018) are demonstrating – but it is not only the number of women on screen that interests me; I am also intrigued by what seems to happen in the matrix of spacetime storytelling when two X chromosomes are present.

It’s hard to believe that at the same time when Kubrick was fussing over every Cartesian detail of his spinning spaceship – not a line out of place or a speck of dust in sight – Vadim was launching his heroine into the cosmos in a fur-lined pod. While Bowman was having his mind blown by the crystalline scintillations of the Star Gate, Barbarella (played by a lustrous young Jane Fonda) was blowing the circuits of an orgasm-inducing machine with the riot of her sexual pleasure. Even when Kubrick aims to invoke a version of ‘letting go’ (a man confronting the unfathomable), he remains in control, making 2001 among the more anally retentive future-visions ever produced.

Kubrick was a legendary control freak, and this very quality seems to be what the movie’s many admirers and would-be emulators in the film world today aspire to. The computer-generated Star Gate-like epiphany in Interstellar (for which the general relativity theorist Kip Thorne was scientific consultant and executive producer) was stifling in its geometric fidelity to general relativistic laws of four-dimensional spacetime. For all the plaudits heaped on 2001, to me the psychedelic sensuality of Barbarella, with its celebration of consensual desire and liquid sensibility, makes it the more groundbreaking work, resonating with today’s scientific trends towards hybridity, dynamical systems and an emergent genomic chimerality.

On its release, the English critic Reyner Banham hailed Barbarella as ‘the first post-hardware SF movie of any consequence’. Under the title ‘The Triumph of Software’, Banham’s essay in New Society called the film a cult masterpiece, and he explicitly juxtaposed it to 2001. Contrasting Barbarella’s software, an ‘ambience of curved, pliable, continuous, breathing, adaptable surfaces’, its fur and leather and animal substances, with the sanitised slickness of 2001, he bemoaned ‘all that grey plastic and crackle-finish metal, and knobs and switches, all that … yech… hardware!’

More recently, the Australian architectural theorist Pia Ednie-Brown has noted that where 2001 revels in man’s ability to kill – that famous bone thrown into the air after an ape realises it can be used as a weapon – Barbarella revels in our pleasure drive. ‘The bone’ versus the boner, I am tempted to say. As its heroine overloads Durand Durand’s sex machine with her unrestrained libidinal delight, the evil scientist admonishes: ‘Have you no shame?!’ One cannot imagine a woman’s pleasure intruding on the sleek perfection of 2001. Ednie-Brown sums up the dichotomy between Kubrick’s controlled straightness and Vadim’s almost animistic magic when she writes: ‘Banham paints a picture of a battle between the behind-the-times hardies and the finger-on-the-pulse softies.’ In Barbarella, ‘hardware is fallible, and software (animate or otherwise) usually wins’.

Barbarella and 2001 represent distinct visions of a space-based future both nascent in the ethos of the 1960s. This was the decade in which IBM launched its Model 360 mainframe, inaugurating the age of business computing, and in some sense Kubrick was upping the computational ante. The name of the murderous computer HAL officially stands for Heuristically programmed ALgorithmic computer, but tech-buffs have long noted that the letters ‘H A L’ immediately precede ‘I B M’ in the alphabet. On the flip-side of the 1960s was flower power, LSD, the Pill and the sexual revolution. Electronics and a Platonist aesthetics on one hand, all shiny, spotless and impersonal. And on the other – psychonautics, sensuality, and the messy playfulness of the body alive to new experience.

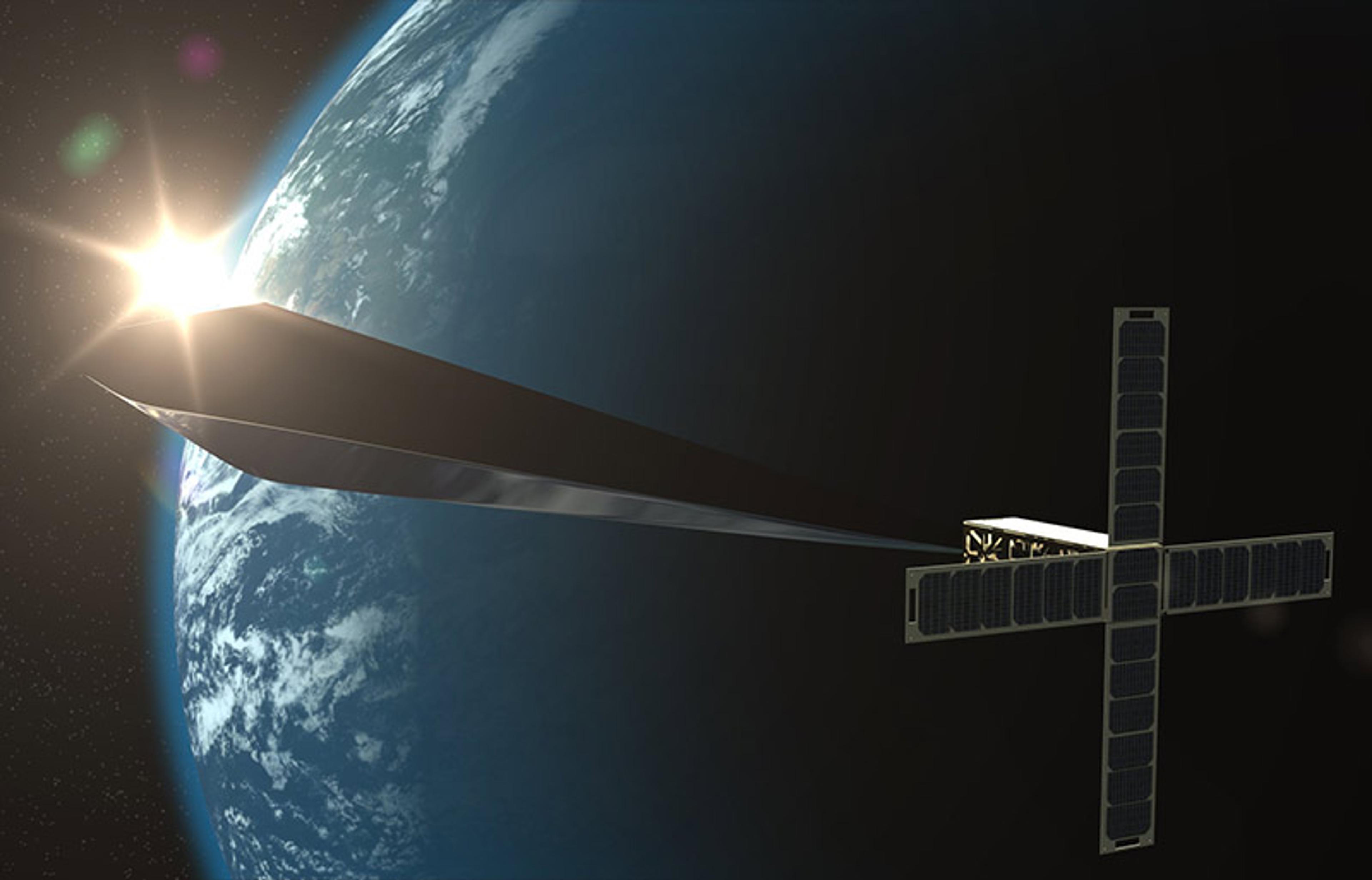

In real life, something akin to the 2001 vision seems to be winning out. Earlier this year, Elon Musk put his shiny-red electric sports car into space atop one of his SpaceX Falcon Heavy rockets, a triumph of phallic hardware. As the Tesla Roadster spins in the void (where it is now tracked liked an asteroid), a spacesuit nicknamed ‘Starman’ sits in the car’s driver’s seat, serenaded by the strains of David Bowie’s ‘Space Oddity’ (1969) – a song that references Kubrick’s film. This month, the American artist Trevor Paglen’s space-based sculpture, Orbital Reflector (a 100-foot-long, reflecting inflatable), gracefully unfolded out of a CubeSat (a small box-like infrastructure) 350 miles (c563 km) above the Earth. Launched out of Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, in another perfect storm of testosterone-fuelled machismo, the Reflector looks like nothing so much as a giant sword thrusting from the holster of the CubeSat.

Paglen is an artist much-admired for making art critiquing government surveillance, and last year he was honoured with a MacArthur ‘genius’ award: so what has propelled him to put a symbol of war into space? ‘Art helps us change the way we see ourselves,’ his project website states. ‘As the 21st century unfolds and gives rise to unsettled global tensions, Orbital Reflector encourages us all to look up at the night sky with a renewed sense of wonder, to consider our place in the Universe, and to consider how we live together on this planet.’ Apparently, the mere glimpse of a glittering object whizzing above our heads will change our consciousness. Then again, given that we seem to be entering a new state of cold war with Russia, and potentially China and Iran, perhaps Paglen’s cosmic sword of Damocles isn’t so off-target. It is telling that the company launching it is now vying for contracts to put US military satellites into space.

Must the bone always win out?

Barbarella posits not only a more peaceful vision but one that’s alive to the virtues of ambiguity and organicism, offering us an imaginative space-world in which body and flesh are part and parcel of the cosmic whole. Here, sex, not weaponry, saves humanity.

The romance of the ‘hard’ is fading, as we realise that glitchiness opens up possibilities for evolution

With its fetishisation of machines and engineering, 2001 strives to escape the ‘prison’ of the flesh, encasing us in a world of sanitised geometry that harks back to the old Pythagorean/Platonic view that allied the spirit or soul with a cosmic realm of perfect Ideas. In this ancient philosophical tradition, soul was contrasted with body, as mind was with matter, and this dualism was intrinsically gendered. Soul, spirit and cosmos were categorised as inherently male, while matter, body and Earth were classed as female. The Pythagorean acolyte studying the mysteries of geometry in 500 BCE was striving to release his soul from its Earthly moorings into the transcendent domain of Pure Number. From this tradition derives the notion of a ‘music of the spheres’ – a set of mathematical relationships supposedly describing the architecture of the Universe. Since the dawn of science, space has long been conceived in the West as an ideal realm bound to mathematical laws, offering exit from the ‘sins’ of the flesh and its messy chaotic incarnations.

Hardware has its intellectual correlate in the ‘hard’ sciences, those most aligned with mathematics, particularly physics. ‘Soft’ – both in ware and science – evokes things less certain, less stable or reliable, and more prone to glitches. The romance of the ‘hard’, however, is beginning to fade, as a realisation takes hold that glitchiness opens up possibilities for transformation and thus evolution. In this sense, Banham was prescient to point out that Barbarella’s software ambience was the more forward-looking approach. It has been said that, while the 20th century was the age of physics, with its search for eternal, stable laws of nature (a modern music of the spheres), the 21st century will be the age of biology and all it offers for revolutionary reimaginings about nature in practice.

Contrast 2001’s Star Gate, a spiky physics-y explosion in space, with Barbarella’s ‘Matmos’, an oozing biomorphic slime that powers the alien city of Sogo and at the end of the film engulfs its iniquitous residents. Ooze – the polar opposite of geometric rigour – is the ultimate retort to Platonism, a horror that defies both form and formal classification, thus threatening the very concept of order, even reason. For ancient Platonists that was what women did: they threatened men’s sense of order. Culturally speaking, Platonic fear of female ‘ooze’ remains a deep current in our society, continually re-expressed in masculine fantasies of future worlds defined by glittering order.

Interesting then, and no coincidence, that a raft of visionary space films feature both concepts of ooze and female stars. What is so frightening about Alien is not so much that its monster kills, as the fact that it does so by entangling itself in our bodies and blurring the boundary of the alien and human. It becomes us, or worse, we become it. It’s like a mother-gone-berserk, an ever-spawning body creeping all over the machinery of space stations, engulfing the hardware in a terrifyingly incalculable software. Part of Ridley Scott’s genius was to realise that it would take a woman protagonist, played with genre-defying audacity by Sigourney Weaver, to do justice to this chimeric, ever-pregnant evil.

In the science-fiction horror film Annihilation, another kind of uncategorisable biomorphism descends upon the Earth – and here the cast that battles it is all-female, led by Natalie Portman and a terrific Jennifer Jason Leigh. A spaceship has crashed near a lighthouse, and around it something scientists call ‘the Shimmer’ is growing. At first it looks benign, a sky-high wall of electromagnetic iridescence, reminiscent of the aurora borealis. But strange things happen within its range, which is growing, and only one man who has gone in has ever come out, and he is now mad from the experience. Hence the decision of the psychologist Dr Ventress (played by Leigh) to send in a team of women.

Whatever our science tells us, the state of the real is more various than what is contained in our equations

Behind the curtain of light, the world at first looks magical: strange, lush flowers bloom over everything; the team encounters a white deer with two heads and blossoms sprouting from its antlers. A biologist named Lena (played by Portman) realises that whatever force is present is mixing up DNA, crossing species boundaries even between animal and vegetable. Soon the chimeras turn nasty: an alligator crossed with a shark attacks while the team crosses a lake; a mutated bear tears someone to shreds. Nature has broken its bounds, defying our category systems and leaving Lena, a final lone traveller, to struggle on in a state of unknowing to the lighthouse and the source of the Shimmer. What happens in the ultimate encounter between her and the alien presence made no sense to me: we seem to be in a state of chimeric abandon where the implication is that anything might turn into anything else. The Shimmer, it seems, just wanted to make something new. Its universe – promiscuous, polymorphous – was pregnant with possibility.

In the film Arrival, the linguist Louise Banks (played by Amy Adams) also encounters alien powers that expand our vision of liquid possibility in what must be one of the loveliest imaginings of extraterrestrials in cinema, here the force of good. Based on a short story by the Chinese American Ted Chiang and directed by the French Canadian Denis Villeneuve, Arrival gives us octopus-like aliens who live in tanks of fog and communicate by drawing complex circular signs created by explosions of ink. The symbols encode a language that changes human perceptions of time and enables the star linguist to have premonitions of the future. Temporal loops weave through the film foiling linear narrative structure, and again we are left with a clear message that whatever our science tells us, the state of the real is more various than what is contained in our equations.

In all these films, the gender of the protagonists seems central to the narrative success. In each case the heroine’s major antagonist is not so much a concrete evil as a kind of ambiguity, which a female psyche seems more readily able to withstand and confront. I do not mean to imply any essentialism here, for men can also have ‘liquid’ minds, and women can be Platonists. Yet the Ancient Greek dualisms continue to course through our cultural tropes and representations, ingraining themselves unconsciously in the mental proclivities of growing boys and girls. It isn’t a coincidence that the ‘hard’ sciences (particularly physics with its lattice-like certitudes) remain overwhelmingly male, while women now outnumber men among students of the ‘soft’ sciences, particularly medicine and biology.

And isn’t ambiguity also a biological paradigm? The message of evolution is that there’s no right answer, no end goal, or even an endpoint. Things change, they transform, they evolve. Living organisms play out patterns of promiscuity without any telos. Moreover, as the American (and notably female) biologist Lynn Margulis showed, a fundamental quality of living things is their chimeric and symbiotic nature – the very cells that make up our bodies are amalgams of simpler ancient cells. We are all crossbreeds. While female characters can, of course, be inclined to the hard sciences – take Jodie Foster’s astronomer Ellie Arroway in Contact (1997), though even here the laws of physics give way to the time-bending pull of love and memory – emerging visions of hybridity and biomorphism in actual and fictional science bode well for the presence of more women in space – at least on screen. In real life, I suspect, the ‘hardies’ will prevail for a long time to come.