I have only the highest respect for the documentarian Ken Burns. He’s America’s storyteller: an unrivalled filmmaker whose creativity, passion and style shine through every history he portrays. My intent is not to dunk on anyone, but rather to start a conversation about how Americans as a society grapple with our own contentious history. Our identities are shaped by the collective experiences of our past, and how we see ourselves in relation to them. Together, we constantly reframe and revise the past to make it make sense to us in the present.

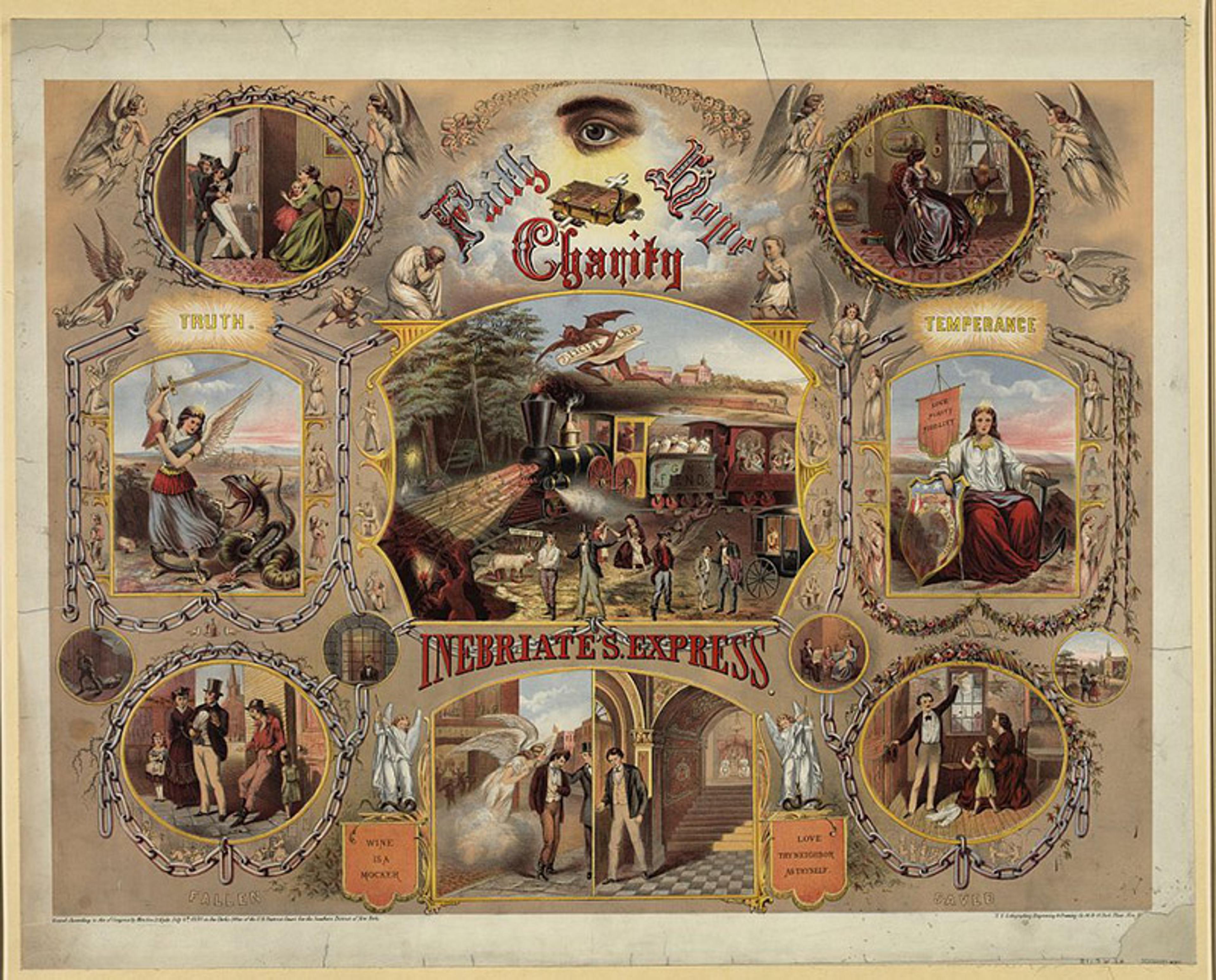

It just so happens that the best place to start that conversation is with Burns and Lynn Novick’s five-and-a-half-hour TV miniseries Prohibition (2011), which covers that most misunderstood chapter in US history, from the 1919 ratification of the 18th Amendment – prohibiting ‘the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors’ – until its repeal by the 21st Amendment in 1933. Prohibition deserves our attention because it reflects what we think we know about history, rather than the actual history itself. It is what the comedian Stephen Colbert called ‘truthiness’ in truth’s stead. The problems start within the first five seconds of the film. The filmmakers set the narrative tone for the entire series with an epigraph – stark white letters centred against a black background:

Nothing so needs reforming as other people’s habits.

Fanatics will never learn that, though it be written in letters of gold across the sky.

It is the prohibition that makes anything precious.

– Mark Twain

Direct. Eloquent. Authoritative. Damning. The framing is clear: temperance activists are the bad guys, ‘fanatics’ hellbent on changing other people’s habits who are dumb enough to ‘never learn’ the most obvious lessons staring them right in the face. The problem is that Twain never really said that. Instead, it is a mosaic of unconnected quotes, spanning different works of fiction and nonfiction over the years.

‘Nothing so needs reforming as other people’s habits’ comes from Pudd’nhead Wilson (1894): Twain’s serialised novel about race, slavery and small-town religion. ‘Fanatics will never learn that …’ was scrawled in Twain’s travel notebook while in London in November 1896 as he extolled the virtues of ‘temperate temperance’. And ‘it is the prohibition that makes anything precious’ came 11 months earlier while in India, as Twain ruminated about Adam, Eve and forbidden fruit during his visit to Allahabad.

When stitched together, they make for a compelling framework for what we feel to be true about temperance and prohibitionism. In the 11 years since the release of the TV series, nobody seems to have noticed this. Still, the epigraph sets the stage for what’s to come. Burns and Novick are gifted storytellers, and every story needs conflict – heroes versus villains, good guys versus bad guys. They’ve cast prohibitionists as the bad guys, as they so often are when prohibition is remembered: hard-headed fanatics intent on dictating ‘other people’s habits’ in a manner most undemocratic and un-American.

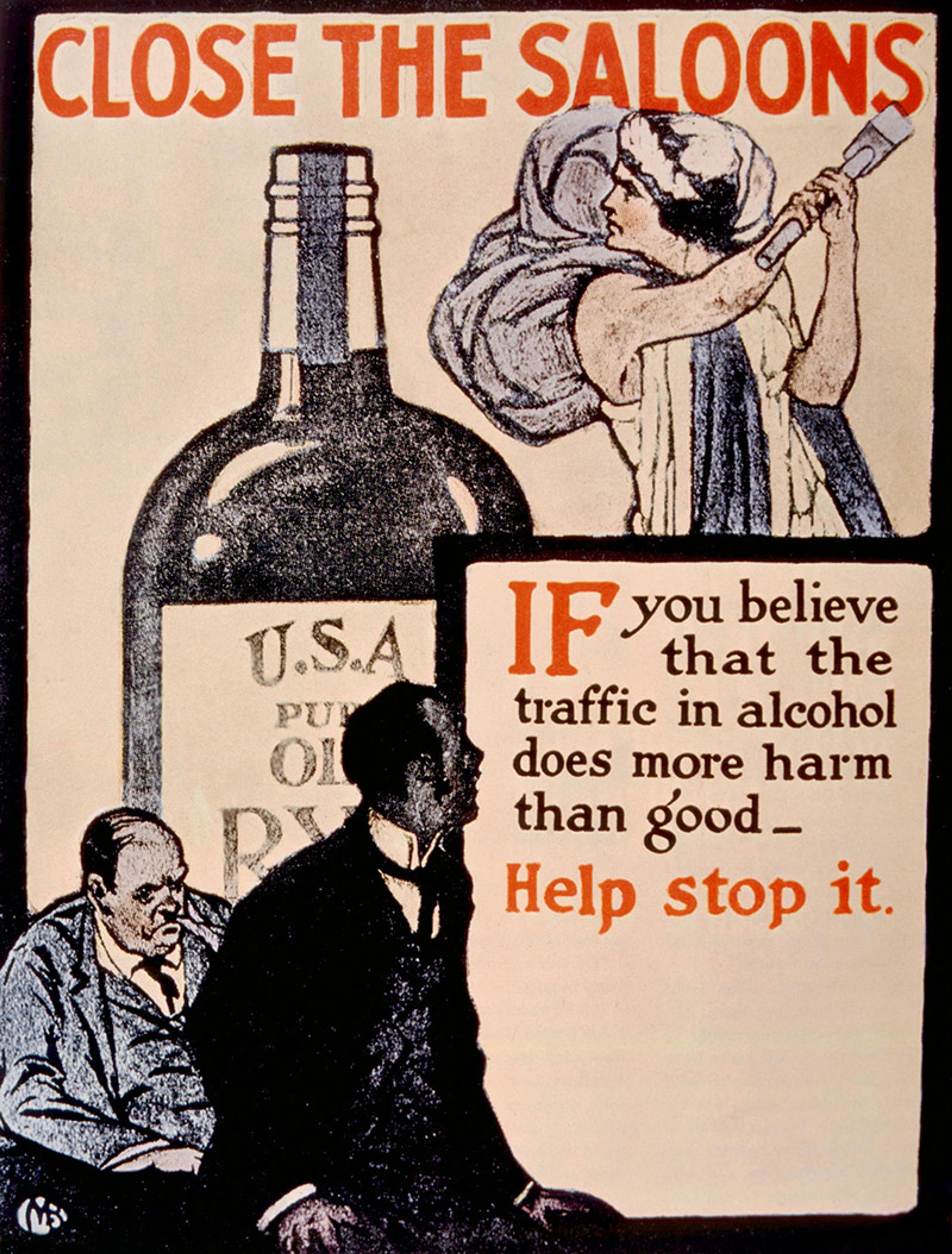

The key to really understanding temperance and prohibition history can be boiled down to one word: traffic. Generations of social reformers and activists – both in the United States and around the world – focused not on the alcohol in the bottle, nor on ‘other people’s habits’, but on what they called ‘the liquor traffic’: unscrupulous sellers who got people hopelessly addicted to liquor for their own profit. The difference between opposing liquor and the liquor traffic is subtle, but hugely important. Liquor is just the stuff in the bottle, but trafficking is about profit and predation; like human trafficking, diamond trafficking or the traffic in narcotics and opioids.

The ‘traffic’ gets mentioned only three times in the Prohibition series. In the first minutes, the 19th-century Presbyterian minister Lyman Beecher – who inspired the modern temperance movement with his series of sermons condemning alcohol in 1826 – declares that ‘like slavery, the traffic in ardent spirits must come to be regarded as sinful.’ After that, the traffic – the thing prohibition was all about – all but disappears from the Prohibition documentary.

Beecher’s Six Sermons on Intemperance (1827) are often credited with kick-starting temperance, though not because they were ‘eloquent’, as Prohibition suggests. Rhetorically, they were pretty unremarkable. Instead, they began an entire social movement by providing a blueprint for action: a boycott to undermine the profit-driven traffic. ‘Let the consumer do his duty,’ Beecher suggested to his temperance followers, ‘and the capitalist, finding his employment unproductive, will quickly discover other channels of useful enterprise.’ Rather than invoking Biblical tales of drunken sinners, Beecher’s Sermons repeatedly cite one verse in particular: Habakkuk 2:9-16: ‘Woe unto him that giveth his neighbour drink, that puttest thy bottle to him, and makest him drunk also.’ From its very inception, then, temperance was a movement for economic justice and community betterment, rather than a gaggle of religious cranks as they’re more conventionally portrayed.

Prohibition was not about the stuff in the bottle, but against the predatory capitalism of the liquor traffic

Prohibition articulates the conventional narrative, as the voiceover by Peter Coyote proclaims that America’s prohibition experience ‘would raise questions about the proper role of government’ and ‘who is – and who is not – a real American’. The framework is clear: the ‘drys’ are the bad guys, and the ‘wets’ are the true patriots, fully exercising their freedom to drink.

In building their case about the ubiquity of booze in early America, Burns and Novick then line up some of the greatest leaders in US history. Yet painting them as pro-liquor patriots requires a very selective reading of the historical record. ‘For most of the nation’s history, alcohol was at least as American as apple pie,’ Prohibition’s narrator explains:

At Valley Forge, George Washington did his best to make sure his men had half a cup of rum every day, and a half a cup of whiskey when the rum ran out … Thomas Jefferson collected fine French wines and dreamed of a day when American vineyards could match them … Young Abraham Lincoln sold whiskey by the barrel from his grocery store in New Salem, Illinois. ‘Intoxicating liquor,’ he later remembered, was ‘used by everybody, repudiated by nobody.’ A young Maryland slave named Frederick Douglass said whiskey made him feel ‘like a president’, self-assured ‘and independent’.

In reality, each of these men – Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, Douglass and scores more – could rightly be listed among America’s great prohibitionists. But how is that possible? Simple: by again recognising that prohibition was not about the stuff in the bottle, but against the predatory capitalism of the liquor traffic.

Did General George Washington ensure that his men had liquor at Valley Forge? Sure. But he also understood that the Quaker colony of Pennsylvania had – at the request of local Native American tribes – a strict prohibition against trafficking the ‘white man’s wicked water’ dating back to William Penn’s Great Law of 1682. That the early colonial Pennsylvania was arguably spared the bloody Indian Wars that plagued the other colonies is credited to the justice and fair play between colonisers and natives embodied in the Quaker prohibition.

When ragtag militias from across the colonies arrived in Valley Forge in 1777, they often supplemented their meagre provisions by trading their liquor with local tribes in defiance of the Quakers’ prohibition. The backlash was so great that General Washington ordered his own prohibition against liquor trafficking, commanding:

All Persons whatever are forbid selling liquor to the Indians. If any Sutler or soldier shall presume to act contrary to this Prohibition, the former will be dismissed from Camp, and the latter receive severe Corporal Punishment.

Washington also required prohibition to maintain discipline in the ranks. Eleven soldiers in each brigade were charged ‘to seize the liquors they may find in the unlicensed tippling-houses’ and ‘notify the inhabitants or persons living in the vicinity of camp that an unconditional seizure will be made of all liquors they shall presume to sell in the future.’ During the Continental Army’s military campaigns, any unscrupulous sutler (civilian provisioner to the army) who ‘adulterated his Liquors or made use of Deficient Measures’ to get the soldiers drunk and make more money off them would be court-martialled.

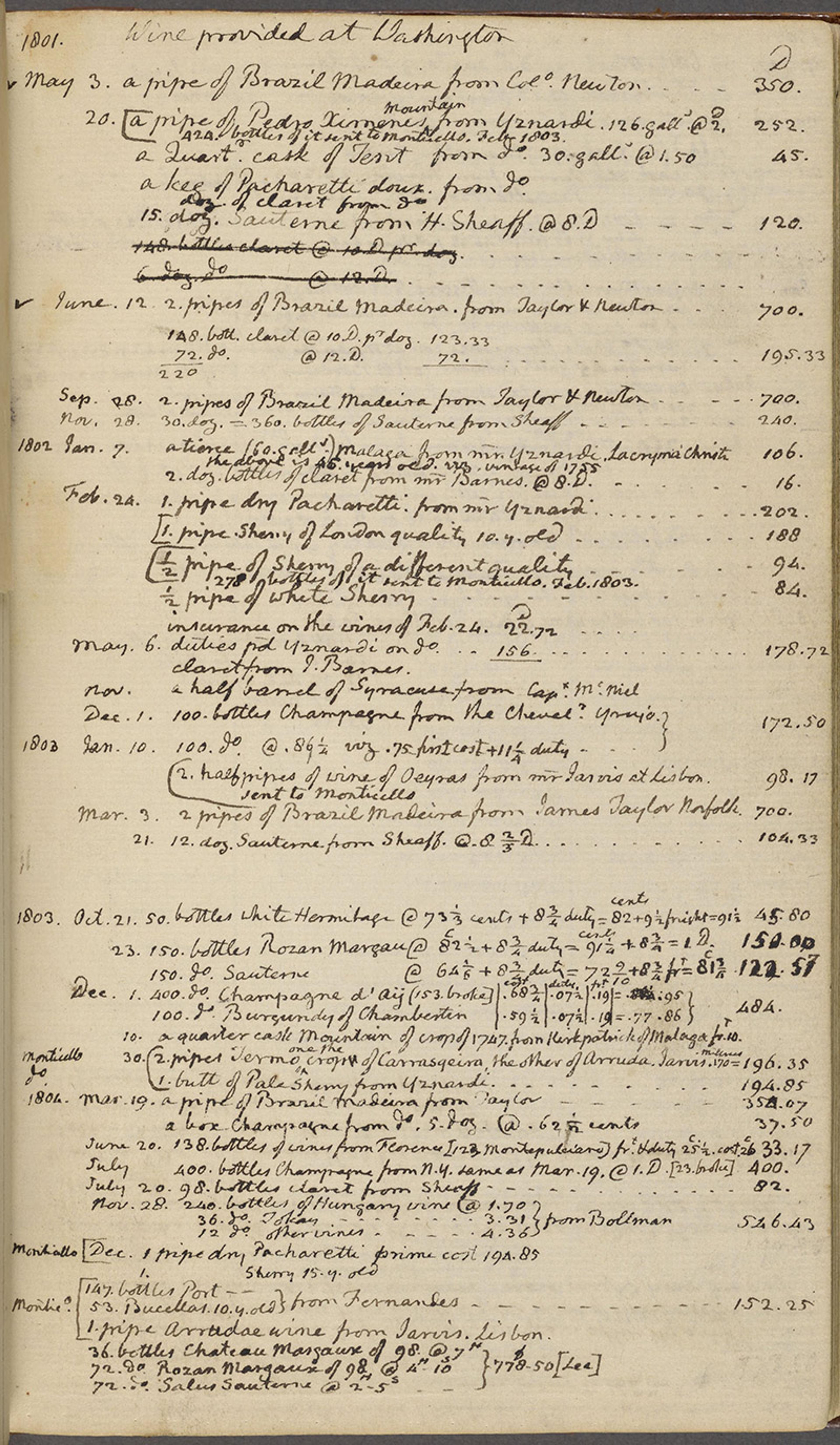

For how often they’re invoked in debates over freedom and liberty, it is noteworthy that many of America’s Founding Fathers – including Washington himself – were prohibitionists. Consider Thomas Jefferson – a famed viniculturist, as Burns and Novick rightly suggest. Yet it was Jefferson himself who pushed for the first US federal prohibition law, more than a century before the 16th Amendment, and a generation even before Beecher’s Six Sermons on Intemperance.

Jefferson’s prohibition was met with near-universal approval by tribal leaders

In 1802, President Jefferson was visited by Chief Mihšihkinaahkwa, or ‘Little Turtle’ of the Miami Confederacy, who travelled from present-day Ohio to explain how white squatters were violating treaty provisions and getting natives drunk to swindle their furs, land and possessions. Little Turtle addressed Jefferson:

Father: when our white brothers came to this land, our forefathers were numerous and happy; but, since their intercourse with the white people, and owing to the introduction of this fatal poison, we have become less numerous and happy.

Moved, President Jefferson took the unprecedented step of petitioning Congress to prohibit the traffic in liquor in the vast ‘Indian Country’ beyond state and territorial jurisdictions. The resulting update of the Act to Regulate Trade and Intercourse with the Indian Tribes (1790) authorised the president to take such measures ‘as to him may appear expedient to prevent or restrain the vending or distributing of spirituous liquors among all or any of the said Indian tribes.’ Bartering Indians’ livestock, crops, clothing, guns or cooking utensils for whiskey risked a fine of $50 and 30 days in jail. Jefferson ordered the secretary of war Henry Dearborn to strip the commercial licences of any white trader caught trafficking in liquor. And while it would be unevenly enforced, Jefferson’s prohibition was met with near-universal approval by tribal leaders.

Admittedly, Washington and Jefferson’s prohibitionism are not common knowledge. On the other hand, Abraham Lincoln’s abstinence was legendary. Honest Abe frequently recounted his ‘first temperance lecture’, when, in 1836 at a community bridge-raising, the strapping 6’4” young man of 27 was challenged to lift a whole barrel of whiskey over his head. He did so with ease. When some whiskey trickled onto his face, Lincoln spat it out, advising his impressed onlookers that ‘if you wish to remain healthy and strong, turn [liquor] away from your lips.’

His political opponent, Stephen Douglas, mocked his temperance tales in the first Lincoln-Douglas debate of 1858. ‘He could beat any of the boys wrestling, or running a foot race,’ Douglas said of Lincoln, and ‘could ruin more liquor than all the boys of the town together’: a jab that met with uproarious laughter from the crowd.

In fact, it was the mudslinging Douglas who charged that Lincoln was once a ‘grocery keeper’ – a well-understood insinuation that he sold whiskey on the sly – intended to paint ‘Honest Abe’ as a canting hypocrite. It didn’t work: Lincoln vehemently denied the baseless character assassination. And, some 160 years of historical research has yet to find any evidence that ‘Abraham Lincoln sold whiskey by the barrel’ … but that doesn’t stop it from being presented as unquestioned fact in Burns and Novick’s Prohibition. It’s not. We do have evidence, however, that when Springfield legislators drafted the Illinois statewide ‘Maine Law’ prohibition in 1854, Lincoln was instrumental in getting it passed.

Finally, Burns and Novick allude to ‘a young Maryland slave named Frederick Douglass [who] said whiskey made him feel “like a president”, self-assured “and independent”.’ This is supremely ironic, as that ‘I used to think I was a president’ line came from Douglass’s address ‘Temperance and Anti-Slavery’ delivered in Scotland in 1846. In it, Douglass explained how:

In the Southern States, masters induce their slaves to drink whiskey, in order to keep them from devising ways and means by which to obtain their freedom. In order to make a man a slave, it is necessary to silence or drown his mind … In no other way can this be so well accomplished as by using ardent spirits!

As a slave, Douglass drank as he was told; but as a free man, he became the most outspoken temperance orator of his day. ‘All great reforms go together,’ Douglass was fond of saying: abolitionism, women’s suffrage and temperance – as Prohibition rightly points out later on. All three opposed the political, social and economic subordination of man by man as Karl Marx would put it. Ultimately, like Lincoln, Douglass vowed ‘to go the whole length of prohibition’.

To Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln and Douglass, one could add a litany of great Americans on the ‘dry’ side of the ledger. Suffragists such as Susan B Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Amelia Bloomer and Sojourner Truth railed against the liquor traffic, as did abolitionists including William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips and Martin Delany; Civil Rights leaders Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Ida B Wells and Booker T Washington; Native American leaders like Black Hawk, Red Jacket and Tecumseh; socialists like Eugene Debs; Democrats including William Jennings Bryan, and famed Republicans including Theodore Roosevelt, who took on corrupt saloonkeepers as New York City Police Commissioner, and later fought for a prohibition plank in his 1912 presidential campaign.

Wait: if we add Roosevelt to Washington, Jefferson and Lincoln – that’s all four guys on Mount Rushmore we could put in the prohibitionist ranks. If prohibitionism really raised questions about who was or wasn’t a ‘real American’, Prohibition could have mentioned that our most American of monuments in reality honours four prohibitionists.

Early on, Prohibition introduces us to the writer and former New York Times editor Daniel Okrent, who regularly appeared in Burns’s award-winning TV series Baseball (1994). In the PBS Preview of Prohibition, Burns and Novick explain how they struck up a conversation with Okrent, who was writing his own book on the subject: Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition (2010). They decided to collaborate, and the Prohibition documentary was born. Consequently, its thesis mirrors that of Last Call, which Okrent himself colourfully poses:

How does a freedom-loving people, a nation that’s built on individual rights and liberties, decide in one kind of a crazed moment, it almost seems, that we can tell people how to live their lives?

Slow down. We need to unpack Okrent’s false assumptions. First – as we’ve already seen – prohibitionism was not about telling people how to live their lives. Second, it wasn’t one ‘crazed moment’, as American prohibition history stretches back centuries, possibly predating the republic itself. Third – and most importantly – let’s focus on that self-image of Americans as a nation of freedom-lovers, dedicated to individual rights and liberties. Perhaps what we conceive of as ‘freedom’ and ‘liberty’ are not the eternal truths we conceive them to be, but are actually contested and constantly in flux. Maybe the reason we don’t understand prohibition history today is because we don’t understand ‘freedom’ today. Or perhaps we don’t understand how prohibitionists understood freedom. If we truly imagine ourselves to be a freedom-loving people, then ‘what do you mean by freedom? For whom? To do what? And to whom?’ are not trivial questions.

Liberating one group often means prohibiting another group from doing its opposite

Responding to Okrent’s question, the New York essayist and novelist Pete Hamill then appears on screen, claiming that ‘virtually every part of the Constitution is about expanding human freedom. Except prohibition, in which human freedom was being limited’ through the 18th Amendment.

Well, no. This again is a triumph of truthiness over truth. The Constitution condoned slavery and the disenfranchisement of women and non-whites. Those who loudly defended slavery, segregation and subordination consistently claimed to be defending that Constitution.

This is why it needed to be amended. We added the 13th Amendment (1865), which prohibited slavery; the 14th Amendment (1868), which prohibited denying equal protection under the law to any US citizens, including formerly enslaved people; the 15th Amendment (1870), which prohibited denial of the right to vote based on race; the 19th Amendment (1920), which prohibited denial of the right to vote based on sex; the 24th Amendment (1964), which prohibited the revocation of voting rights due to a poll tax; and the 26th Amendment (1971), which prohibited denial of the right to vote based on age, 18 and over.

Liberating one group often means prohibiting another group from doing its opposite. In ‘expanding human freedom’ for Black people, the 13th Amendment quite explicitly took away white Americans’ perverse freedom to own slaves. The fundamental question about ‘freedom’ is always: who has the freedom to do what and to whom?

Just as the 13th Amendment proclaimed that no one has the freedom to buy, sell or own other human beings for their own profit, the 18th Amendment (1919) said that no one has the freedom to enslave others through addiction for their own profit. The 18th Amendment said nothing about ‘reforming other people’s habits’: it didn’t outlaw drinking. It banned ‘the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors’, which is to say it prohibited trafficking. No American has the innate right to subjugate another. The liquor traffic – like slavery, misogyny and discrimination – was an impediment to liberty. Removing that impediment would promote greater freedom for all, which was in concert with the country’s loftiest ideals – not opposed to them.

This is how prohibitionists understood what they were doing, and why they were supported by so many freedom-loving Americans. They wrote books like Prohibition: An Adventure in Freedom (1928) or The Second Declaration of Independence; or, a Suggested Emancipation Proclamation from the Liquor Traffic (1913) without a hint of irony. Prohibitionists saw themselves as enablers of democracy and self-determination, and defenders of the community’s right to exercise sovereignty over their own affairs.

Interestingly, their opponents saw them that way, too. When the colourful American prohibitionist William E ‘Pussyfoot’ Johnson travelled to London in 1919 – where an anti-prohibitionist street riot would ultimately claim the use of his right eye – the Daily Mail sat down to interview this curious specimen. ‘Pussyfoot is no moral fanatic, no anaemic prince of virtue, no puri-tyrannical old woman, no suburban Torquemada,’ the newspaper wrote. ‘It just so happens to be his business job of work in life to make the world soft for democracy.’

The fault lies with a fundamental shift in how we understand freedom itself

Lest you think this is some radical ‘revisionist history’, the US Supreme Court saw it that way, too. In the lead-up to the 18th Amendment, they ruled on numerous prohibition cases. In Crowley v Christensen (1890), the Supreme Court found that ‘There is no inherent right in a citizen to thus sell intoxicating liquors by retail. It is not a privilege of a citizen of the State or of a citizen of the United States.’ The court was clear and unambiguous.

The Supreme Court had addressed the ‘freedom to drink’ argument directly in Mugler v Kansas (1887), roundly determining that any alleged right to drink alcohol

does not inhere in citizenship. Nor can it be said that Government interferes with or impairs any one’s constitutional rights of liberty or of property when it determines that the manufacture and sale of intoxicating drinks for general or individual use as a beverage are or may become hurtful to society, and constitute, therefore, a business in which no one may lawfully engage.

So why is it so difficult for us to wrap our heads around this? In my book Smashing the Liquor Machine: A Global History of Prohibition (2021), I conclude the fault lies with a fundamental shift in how we understand freedom itself.

Before the Second World War, so-called neoliberalism was a fringe economic doctrine, premised on the economic decision-making of the individual to promote their own wellbeing. Pioneering economists Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek and later Milton Friedman argued that any infringements of a citizen’s economic liberties – the right to buy, sell, and consume – were necessarily infringements upon their political liberties as well. As these doctrines moved into the mainstream with Thatcherism in the UK and Reaganomics in the US, for the past 40 years we’ve lived in a world where political liberties and economic freedoms have blurred together.

That’s not true in many non-Anglo Saxon parts of the world – especially continental Europe – where there’s still a firewall between political liberties and economic freedoms. It was also certainly not true in the US prior to the Second World War. This is a major distortion in the fabric of US history, and the Prohibition Era, as well as everything leading up to it, lie on the other side. The conclusion is clear: we fail to properly understand prohibitionism not because of anything they did back then, but because we’ve changed.

What leads Burns and Novick’s Prohibition astray are history’s twin logical fallacies: hindsight bias – confidently overestimating our knowledge of a highly contingent past – and the narcissism of the present, in which we project our own contemporary beliefs back in time and to other contexts where they don’t necessarily apply. It falsely assumes that the core issues of prohibition and freedom – and the narratives and identities that we’ve built upon them – were understood the same way today as they were way back when, as opposed to being contested and constantly in flux.

Prohibition history has always been told as white people’s history

It is not as though Burns and Novick went rogue in covering prohibition. Their job – as America’s storytellers – is not to break new ground into history, but to ‘stand on the shoulders of giants’, and make historians’ conventional wisdom relatable to their viewers. Those historians have gotten it increasingly wrong, and have taken our history with them. Historians’ analyses have been overlaid with all manner of their own latent biases – compounding over time – which obscure rather than illuminate the true historical record.

The most telling biases are based on race and gender. Women’s empowering activism was crucial, both to the temperance and to the suffragist movements – for which they’ve been roundly vilified ever since. But rather than being unjustly pilloried in the history books, similarly disenfranchised and disempowered Native American and African American minorities have simply been written out of them. Even worse, their plight was overwritten by colonisers’ victim-blaming narratives: claiming Black and Native susceptibility to drunkenness justified their subordination to white dominance, with their leisure needing to be ‘disciplined’. Consequently, prohibition history has always been told as white people’s history.

Burns and Novick simply reflect historians’ conventional wisdom. All of the main characters profiled in the entire Prohibition miniseries are white. With the exception of a cameo by the African American historian Freddie Johnson (who talks about obtaining medical prescriptions for alcohol), all of the experts in Prohibition are white. The documentary simply reinforces the historically dominant white narratives, in which Black and Native prohibitionism are passed over in silence.

Again, this is not to slake Burns and Novick as filmmakers. They are sensitive to ensure their depictions, images and videos reflect the diversity of this country – within the bounds of the story being told. It is the story that is circumscribed.

In fact, the person most keenly aware of the power of racially dominant historical narratives may be Burns himself. In a recent project, Burns and fellow US filmmaker Stephen Ives recount the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864, in which hundreds of peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho villagers were mercilessly slaughtered by 700 soldiers of the First and Third Colorado Cavalry. After chronicling the brutal attack, Burns himself narrates the decades-long struggle by Native tribes to have the event – and the National Historic Site – be recognised as the Sand Creek Massacre. It had been ‘recast as a “battle” in the collective memory of many white Americans’ – as between two belligerent sides, rather than one – ‘and celebrated as a key event in Colorado’s journey to statehood’.

Acknowledging the massacre forces us to confront a shameful history, and makes us stronger as a nation. ‘It is a powerful example of how our history can be mythologised, omitting shameful chapters, and reinforcing insidious narratives,’ Burns says. ‘How we remember history is also a part of our history.’ Indeed.

This is not an accusation of wilful deceit by an iconic documentarian. In fact, this story isn’t really about Burns at all. In the end, it is about the stubborn power of entrenched historical narratives, and the baggage that comes with them. Movies, documentaries and dramatisations are how the public engages with the past, and how we view ourselves in relation to it. But they are not crystal-clear reflections of what was. Instead, they contain the accumulated biases – overt and latent – of generations of historians. That neither critic nor historian seems to have noticed or called out these glaring historical inaccuracies in the decade since Prohibition’s release only proves the point. This is all the more reason to scrutinise our own shared historical conceptions, misconceptions and understandings. It’s what Burns would want.

Ultimately – when it comes to Prohibition – it is not that Burns failed history; but rather that we historians have failed Burns.