‘Language is fossil poetry. As the limestone of the continent consists of infinite masses of the shells of animalcules, so language is made up of images, or tropes, which now, in their secondary use, have long ceased to remind us of their poetic origin.’

– from the essay ‘The Poet’ (1844) by Ralph Waldo Emerson

‘Metaphors … become more literal as their novelty wanes.’

– from the book Languages of Art (1976) by Nelson Goodman

If Ralph Waldo Emerson was right that ‘language is fossil poetry’, then metaphors undoubtedly represent a significant portion of these linguistic remnants. A particularly well-preserved linguistic fossil example is found in the satirical TV show Veep: after successfully giving an interview designed to divert the public’s attention from an embarrassing diplomatic crisis, the US vice-president – portrayed by the outstanding Julia Louis-Dreyfus – comments to her staff: ‘I spewed out so much bullshit, I’m gonna need a mint.’

When used properly, metaphors enhance speech. But correctly dosing the metaphorical spice in the dish of language is no easy task. They ‘must not be far-fetched, or they will be difficult to grasp, nor obvious, or they will have no effect’, as Aristotle already noted nearly 2,500 years ago. For this reason, artists – those skilled enhancers of experience – are generally thought to be the expert users of metaphors, poets and writers in particular.

Unfortunately, it is likely this association with the arts that has given metaphors a second-class reputation among many thinkers. Philosophers, for example, have historically considered it an improper use of language. A version of this thought still holds significant clout in many scientific circles: if what we care about is the precise content of a sentence (as we often do in science) then metaphors are only a distraction. Analogously, if what we care about is determining how nutritious a meal is, its presentation on the plate should make no difference to this judgment – it might even bias us.

By the second half of the 20th century, some academics (especially those of a psychological disposition) began turning this thought upside down: metaphors slowly went from being seen as improper-but-inevitable tools of language to essential infrastructure of our conceptual system.

Leading the way were the linguist George Lakoff and the philosopher Mark Johnson. In their influential book, Metaphors We Live By (1980), they assert that ‘most of our ordinary conceptual system is metaphorical in nature’. What they mean by this is that our conceptual system is like a pyramid, with the most concrete elements at the base. Some candidates for these foundational concrete (or ‘literal’) concepts are those of the physical objects we encounter in our every day, like the concepts of rocks and trees. These concrete concepts then ground the metaphorical construction of more abstract concepts further up the pyramid.

Lakoff and Johnson start from the observation that we tend to talk of abstract concepts as we do of literal ones. For instance, we tend to speak of ideas – an abstract concept that we cannot directly observe – with the same language that we use when we speak about plants – a literal concept with numerous observable characteristics. We might say of an interesting idea that ‘it is fruitful’, that someone ‘planted the seed’ of an idea in our heads, and that a bad idea has ‘died on the vine’.

The goal of an argument under the ‘dance’ framing would not be to ‘win’ it but to produce a pleasing final product

It is not just that we speak this way: Lakoff and Johnson take us to really understand and make inferences about the (abstract) concept of an idea from our more tangible understanding of the (concrete) concept of a plant. They conclude that we have the conceptual metaphor IDEAS ARE PLANTS in mind. (Following convention, I will capitalise the conceptual metaphor, wherein the abstract concept comes first and is structured by the second.)

Lakoff and Johnson further illustrate this with the following example. In English, the abstract concept of an argument is typically metaphorically structured through the more concrete concept of a war: we say that we ‘win’ or ‘lose’ arguments; if we think the other party to be uttering nonsense, we say that their claims are ‘indefensible’; and we may perceive ‘weak lines’ in their argument. These terms come from our understanding of war, a concept we are disconcertingly familiar with.

The novelty of Lakoff and Johnson’s proposal is not in noticing the ubiquity of metaphorical language but in emphasising that metaphors go beyond casual speech: ‘many of the things we do in arguing are partially structured by the concept of war.’ To see this, they suggest another conceptual metaphor, ARGUMENT IS A DANCE. Dancing is decisively a more cooperative enterprise than war – the goal of an argument under this framing would not be to ‘win’ it but to produce a pleasing final product or performance that both parties enjoy. The dynamics of how we’d think about an argument under such a framing would be very different. This highlights the role of metaphors in creating reality rather than simply helping to represent it.

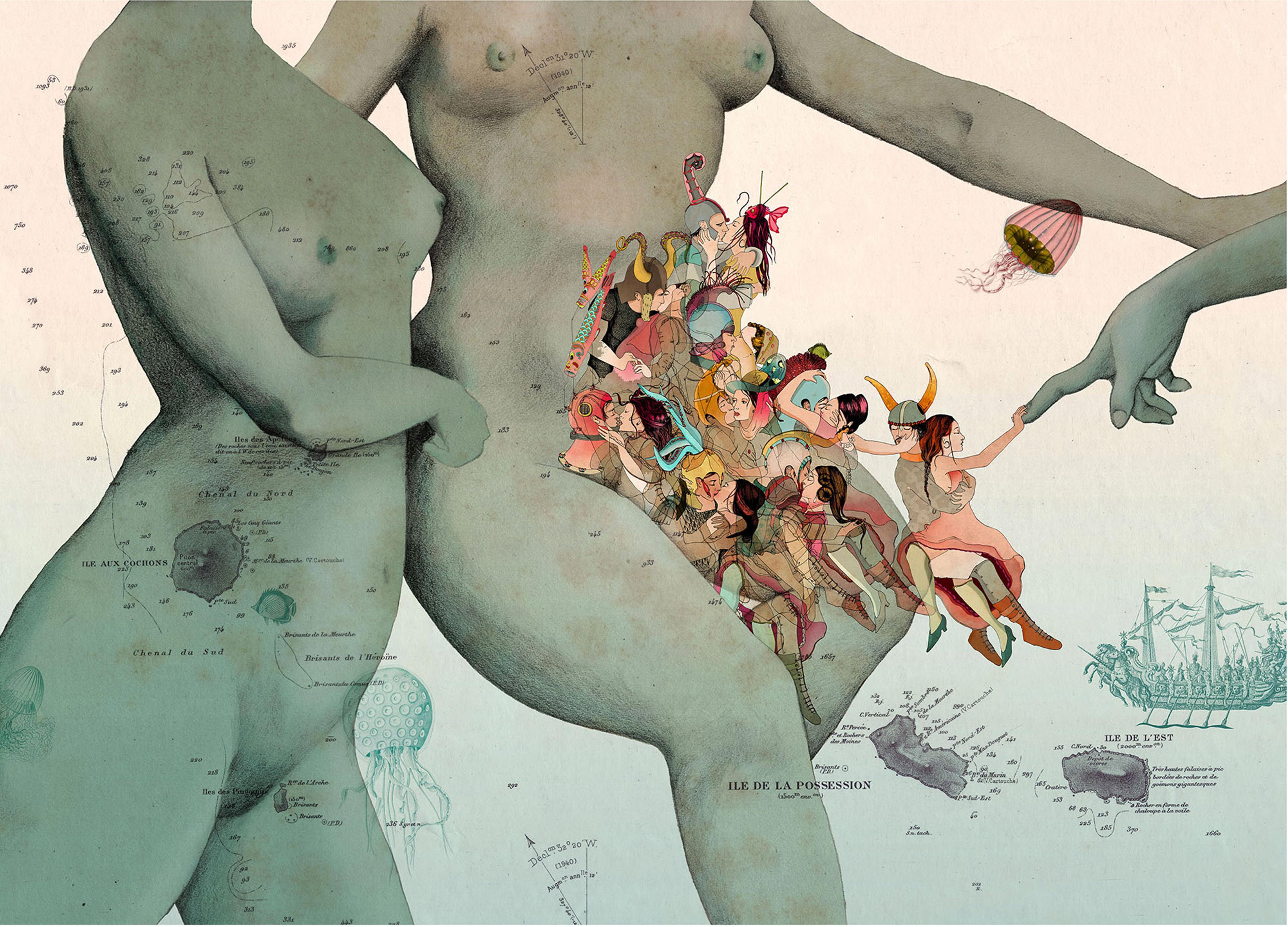

Metaphors thus seem to provide the foundation of how we conceptualise abstract concepts (and, therefore, much of the world). A single metaphor, though, only partly structures complex concepts – typically, more are used. Take the concept of romantic love. A widespread conceptual metaphor in a variety of languages is ROMANTIC LOVE IS A JOURNEY. It is common to say that a relationship is ‘at a crossroads’ when an important decision must be made, or that people ‘go their separate ways’ when they split. (Charles Baudelaire’s 1857 poem ‘Invitation au voyage’ is a notable play on this conceptual metaphor, where the speaker invites a woman to both a metaphorical and a literal journey.) Again, these metaphorical conceptualisations greatly affect how we act in a relationship: without the notion of a crossroads in my relationship, I probably would not have considered the need for a serious conversation with my partner about our state.

But love, so important for human life, is partially structured by innumerably many other metaphors. Another common one – perhaps fossilised by Ovid’s poem with the same title – is ROMANTIC LOVE IS WAR. It is common to read that one party ‘conquers’ the other or is ‘gaining ground’ with an initially reluctant partner, and that one’s hand can be ‘won’ for marriage. (Already with this example, we see that pervasive metaphorical framings can have not-so-subtle misogynistic undertones.)

To the eternal question ‘What is love?’, conceptual metaphor theory has an answer: the bundle of metaphors that are used to conceptualise it. LOVE IS A JOURNEY and LOVE IS WAR are two instances of this bundle that highlight and create different aspects of the concept of love.

Any speaker knows that the language we use matters, and that there is a complex feedback between the language we speak and the thoughts we think. Empirical studies support this intuition: having different conceptual metaphors in mind, people will tend to make different decisions in the same context (a reasonable indicator that they harbour different concepts).

Metaphors influence opinions, including how people view climate change or the police

In one such study, two groups were shown a report on the rising crime rate in a city. One group received a report that opened with the statement ‘Crime is a virus ravaging the city,’ while the other group received a report that started with ‘Crime is a beast ravaging the city.’ The two groups were thus primed to metaphorically structure the concept of crime with two distinct concepts: virus or beast. They were then asked about which measures they would implement to solve the crime problem. Those who were primed to have the conceptual metaphor CRIME IS A BEAST were much more likely to recommend punitive measures, such as increasing the police force and putting criminals in jail (just as one would, presumably, put a beast in a cage). Those who were primed to entertain CRIME IS A VIRUS tended to suggest measures that are associated with epidemiology: to contain the problem, to identify the cause and treat it, and to implement social reforms. Remarkably, the participants were not aware of the effect these metaphorical framings had on their choices. When asked why they chose the solutions they did, respondents ‘generally identified the crime statistics, which were the same for both groups, and not the metaphor, as the most influential aspect of the report.’

Crime is not an outlier: studies with similar setups strongly suggest that the choice of conceptual metaphors significantly influences the opinions and decisions of individuals in a variety of settings. Among others, these include how people view the threat of climate change, their attitudes towards the police, and their financial decision-making.

The significance of metaphors and analogical thinking is even more pronounced in children. Spearheaded by work by the cognitive scientists Dedre Gentner and Keith Holyoak, the study of analogical reasoning is now a flourishing research programme. There is considerable evidence of the importance of the use of analogy in the development of children; studies suggest that relational thinking – essential for making analogies – predicts children’s test scores and reasoning skills. Though many of these studies have yet to be replicated, metaphors seem to literally shape the brain.

It is also not an exaggeration to say that metaphors scaffold science, that conceptual system of organising knowledge. In Polarity and Analogy (1966), a fascinating study of the use of analogies and metaphors in ancient Greek science, the historian Sir Geoffrey Lloyd makes a compelling case for the importance of analogies in guiding early scientific thought. For example, Lloyd highlights how analogies with political organisations shaped views about the cosmos. A typical ancient Greek approach to explain the Universe involved postulating fundamental substances and then explaining how these interact (Empedocles famously proposed that the four fundamental substances are fire, air, water, and earth). To help determine the relations between the substances, these ancient scientists would invoke analogies with their political systems. One prominent conceptual metaphor used was the COSMOS IS A MONARCHY, where a single substance has supreme power over the others. This language is still used in modern-day physics when we hear that the laws of the Universe govern our world. Another prevalent conceptual metaphor was the COSMOS IS A DEMOCRACY; this framing, which appeared only after democracy was established in Athens, holds that the fundamental substances are in equal rank and function with a sort of contract among themselves.

This use of political metaphors is not just stylistic. Lloyd writes that ‘time and again in the Presocratics and Plato, the nature of cosmological factors, or the relationships between them, are understood in terms of a concrete social or political situation’. From the point of view of conceptual metaphor theory, this makes sense: to understand a new, abstract and invisible concept (the fundamental substances of the Universe), it is only natural that these thinkers analogised it to phenomena they had direct experience with (their political organisation).

Metaphors and analogies are not mere artefacts of ancient science but also vital instruments of the contemporary scientific orchestra. They help formulate and frame theories: political metaphors, not unlike those used by the ancient Greeks, are frequent in modern biology, which is rife with the language of ‘regulators’ – invoking the regulatory bodies now present in modern governments. These metaphors highlight the checks and balances that exist within complex biological systems, paralleling the way government regulators maintain order in their respective domains. Military metaphors are also common: the immune system is repeatedly framed as an army that protects the body from ‘invading’ pathogens. Metabolic pathways are also often analogised to freeways, equipped with ‘bypasses’, and sometimes experiencing ‘roadblocks’ or ‘traffic’, as noted by the philosopher Lauren Ross.

Analogies are also central for generating new hypotheses (what we might call scientific creativity). A notable example is that of Charles Darwin’s idea of natural selection, which he came to by drawing an analogy with the selective practices of farmers. Roughly, the analogy could be cashed out as follows: nature selects organisms for fitness in a similar way that farmers select the best crops for taste, disease resistance and other attributes.

Given the nature of our metaphorical minds, it is worth asking: are our conceptual metaphors apt? We owe it to ourselves and others to reflect on the appropriateness of the metaphors we employ to frame the world. These choices – conscious or not – can be constructive or disastrous.

Consider the metaphorical discourse between doctors and patients in cancer care. These conversations shape how the patients judge their own experience and so, inevitably, impact their wellbeing. War metaphors are ubiquitous, which says a lot about our culture. Cancer care, unsurprisingly, is no different: patients are often said to be ‘fighting a battle’ with cancer and are judged on their ‘fighting spirit’. Research, however, suggests that this conceptual metaphor causes real harm to some patients. For example, the Stanford palliative care doctor Vyjeyanthi Periyakoil found that ‘opting to refuse futile or harmful treatment options now becomes equivalent to a cowardly retreat from the “battleground” that may be seen as a shameful act by the patient’. In other words, a patient who is already preoccupied with dying from the disease may feel the additional – unnecessary and cruel – shame for not continuing to ‘fight’.

An oncologist review article urges nurses and doctors to rethink the usefulness of this militaristic metaphor. The alternative proposed is to use the conceptual metaphor CANCER IS A JOURNEY to frame the patient experience. Reconceptualising it in this way leads to different thoughts: cancer is not a battle to be conquered, but an individual and unique path to navigate; the experience with the disease is not something that ends (as war typically does) but an ongoing neverending process (with periodic hospital visits to monitor any recurrence).

Any suggested conceptual re-engineering needs to be tested to see if it actually works better than the previous framing. This seems to be the case for the journey metaphor: patients who reframed their cancer experience in this way had a more positive outlook, generally increased wellbeing and reported spiritual growth. (I suspect that a similar mindset switch would do a lot of good for people suffering from mental health and chronic diseases, since these are even less obviously distinct entities that need to be ‘fought’, but rather experiences patients have to live with, often for the rest of their lives.)

The war metaphor is also known to increase racist sentiments, something we’ve seen during the pandemic

Being clear at both linguistic ends – patient and doctor, and more generally non-expert and expert – on what metaphors are used to conceptualise illness is critical: two interlocutors speaking about what they think is the same concept, but each framing that concept with a different metaphor, is a recipe for miscommunication. And miscommunication can be painful, especially when one party is experiencing a disease that profoundly consumes every aspect of their being.

We should also question current metaphorical framing of complex societal challenges – writing in The New York Times in 2010, the economist Paul Krugman warns that ‘bad metaphors make for bad policy’. The COVID-19 pandemic is a case in point: the long-standing practice to employ war metaphors to speak about pandemics was a trend observed with the coronavirus outbreak as well. Common phrases included ‘nurses in the trenches’, healthcare workers as a ‘first line of defence’, and politicians announcing that the nation is at ‘war’ against an invisible enemy.

At first examination, war metaphors might seem to convey the gravity of the situation and mobilise people for action. But it is important in such cases to consider the unintended consequences that come with a choice of metaphorical framing. War, for example, generally requires intense nationwide mobilisation for action, whereas plagues require the majority of the population to stay home and do nothing. The war metaphor is also known to increase racist sentiments, something we’ve seen during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As an alternative, some linguists have suggested that a more fitting metaphor would be to reconceptualise it as the PANDEMIC IS A FIRE, since this emphasises the urgency and destructiveness of the health crisis, while avoiding some of the drawbacks of the war metaphor. This is not to say that it is wrong or unethical to have in mind the PANDEMIC IS A WAR – it could be that the war framing is in fact the best to mobilise people and motivate them to stay home during pandemic emergencies. The point is, rather, that knowing its potential problems should prompt us to use the metaphor with extra precautions.

It should be clear that the power a choice of metaphor(s) has in structuring our thoughts makes the tool vulnerable to be hijacked by grifters and politicians to advance their own agenda. To take but one example, in 2017 Donald Trump used a version of Aesop’s fable of The Farmer and the Snake to metaphorically frame immigrants in a negative light. The fable recounts a farmer who, on her way home, finds a freezing and ill snake. Taking pity on the creature, the woman brings it home and keeps it warm. On her way back from work the next day, she sees that the snake is healthy again. Consumed by joy, she gives the snake a hug. The snake, in turn, fatally bites her. The farmer asks the snake why it would do such a thing; feeling no remorse, the snake says: ‘You knew damn well I was a snake before you took me in.’ By reading out this story in a speech, Trump primed the audience to conceptualise that IMMIGRANTS ARE SNAKES, and the UNITED STATES IS A WOMAN. The philosopher Katharina Stevens makes a convincing case that Trump used this fable to lend support to the belief that immigrants are a national security threat (just as the snake is a threat to the woman).

Metaphors can also perpetuate a language of dehumanisation that paves the conceptual road for the worst kinds of human atrocities. During the Rwandan genocide, the country’s main radio station played a key role in framing how its Hutu majority saw the Tutsi minority: they repeatedly used metaphors to dehumanise the Tutsis – a well-known example is of analogising Tutsis to cockroaches. When such a metaphor is so internalised that it structures the concept people have of such a group, it follows almost immediately that they will want to get rid of them (just as they would of actual cockroaches). That is what happened. The particularly frightening power of conceptual metaphors is not that a group is seen unfavourably and then, to emphasise this point of view, referred to by dehumanising metaphors. Rather, it is that the metaphorical construction used to frame a particular group in the first place is a reason why the other group sees them that way. Lakoff was right when he warned that ‘Metaphors can kill.’

Suppose we notice that we harbour concepts whose metaphorical foundation causes harm. Can we really reconstruct the concept with a different metaphorical foundation? Lakoff and Johnson think so – I hope they are right, even if doing so is no easy task.

The first step is to notice the metaphor; this is not always obvious. One way of reconstructing part of the history of feminist thought is to say that the thinkers spotted the pernicious metaphor of framing women as objects in the conceptual structure of the patriarchal society around them. Among those who pointed out the pervasive conceptual metaphor WOMEN ARE OBJECTS was the feminist Andrea Dworkin, who wrote that ‘objectification occurs when a human being … is made less than human, turned into a thing or commodity’. Though in contemporary discourse there is an acknowledgment that this conceptualisation is widespread (consciously or not), at the time of writing Woman Hating (1974), Dworkin explicitly emphasises the need to make people aware of it.

Once the conceptual metaphor is explicitly spelled out, the next step is to argue why it is undesirable and in need of change. With objectification, many ethical problems arise; significantly, the autonomy of the woman is reduced, which enables unbalanced power dynamics. This is a considerable harm in need of imperative remedy. To fight back, feminist writers have searched for the cause of this metaphorical conceptualisation and sought – and continue to seek – to dismantle it. (Dworkin and her fellow feminist Catharine MacKinnon take pornography to be a primary cause, though this has been challenged by other thinkers.)

The most important first step is to be aware that a concept we have is constructed metaphorically

The deeper a metaphor is rooted in the collective psyche, the harder it is to replace. But, even when ingrained, small changes can sometimes have important effects. One such minor change was done by The Guardian: in 2019, they changed their style guide to advise authors to use the term climate ‘crisis’ or ‘emergency’ instead of climate ‘change’. The editor-in-chief, Katharine Viner, justified this by noting that the current language sounded ‘rather passive and gentle when what scientists are talking about is a catastrophe for humanity’. This sort of change in language can slowly alter how readers understand the gravity of the climate situation.

Much research still needs to be done. How can we know whether a conceptual metaphor is doing what we want of it? What features do good alternative conceptual metaphors have in common? How can we successfully dismantle the foundational metaphor of a concept? Some harmful metaphors will be harder to free ourselves from than others; however, the most important first step is to be aware that a concept we have is constructed metaphorically. Finding these should, in many cases, be rather easy: after all, as the philosopher Nelson Goodman observes, ‘metaphor permeates all discourse, ordinary and special, and we should have a hard time finding a purely literal paragraph anywhere.’

Metaphors are (metaphorically) woven into the fabric of our language and thought, shaping how we grasp and articulate abstract concepts. We should therefore feel free to prudently explore alternative metaphors and judge whether they perform better. A collective effort to notice and change the metaphors we use has enormous potential to reduce individual and societal harm.