In the surreal aftermath of my suicide attempt and amid the haze of my own processing, my best friend visited me in the hospital with a (soft-bound and thus mental-patient-safe) copy of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest under his arm. It was the spring of 2021. A couple months earlier, I had slipped in a tub, suffered a concussion, and triggered my first episode of major depression, and those had been the most difficult months of my life.

Though a lifelong ‘striver’ and ‘high achiever’, nothing I’ve ever done was harder than waging that war against myself while catatonic on that Brooklyn sofa. This was an inarticulable and so alienating war, one during which, at every moment, it was excruciating and terrifying to exist at all. I thought I knew the extent of my own mind’s capacity to torture itself, to hurt me, and what this thing we call depression can really be like. But I had been wrong.

For anyone who hasn’t experienced it at its worst, I now think it is psychologically impossible to imagine. It may even prove impossible for those who have experienced to still remember it after the fact, just as someone who temporarily perceives a fourth dimension wouldn’t really, fully remember what it was like once the perception is lost, only facets of the larger, unfathomable thing.

So maybe I can’t really remember, either: but I can recall thinking again and again these staggered reflections I’m writing now. Some of the swirling emotions that distressed and disoriented me on that sofa also remain faintly accessible, like the crippling inability to make any decisions, no matter how small, such that even contemplating a choice among some host of mine’s warmly offered selection of teas would incapacitate me with self-loathing and breathless, gushing tears. I remember hopelessly trying to make myself feel even the glimmer of anything good, turning to everything – the music, the friends – that had brought me so much joy before, only to find that I could no longer feel any of it but rather just, from somewhere afar, see and long for it while watching as the ever-darkening blackness in me instead consumed it all.

I remember the debilitating guilt and shame that emerged for everything I had ever done, including for having the audacity to keep existing for so long. And I remember an overwhelming empathy as I wondered how many others felt this way in the history of the world, imagining the vastness of all these solitary confinements within our minds across space and time. At the same time, it was unfathomable to me that anyone had ever felt like this, or that there could even be enough darkness in the universe to realise the experience more than this once.

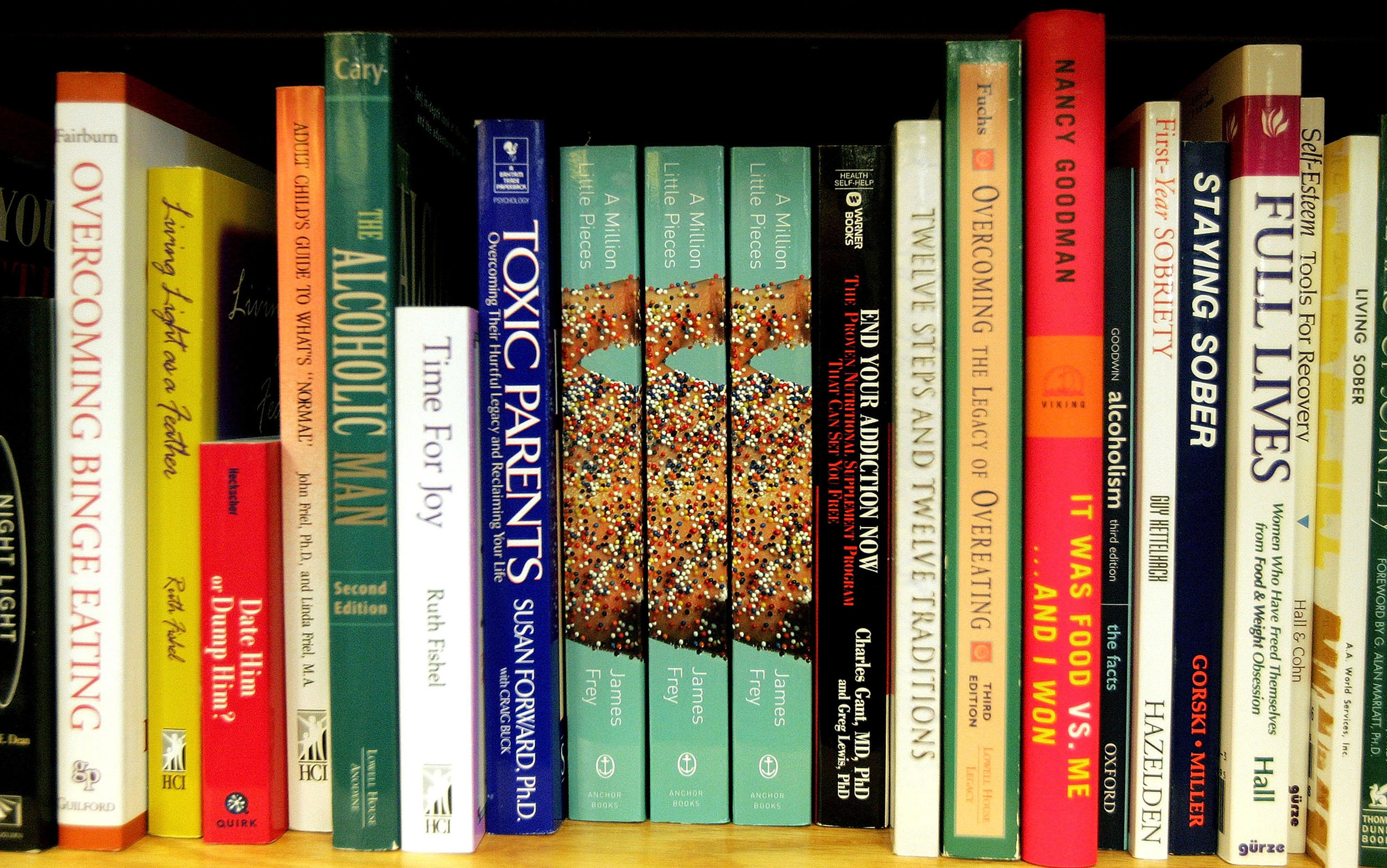

From the days following my injury through the several months after, my ultimate challenge on that sofa was finding a way to endure the passage of time. I needed something to help me get through each moment and make it to the next one while still intact. I couldn’t actually do anything, but staring into space (or even watching TV) kept me vulnerable, as the cognitive passivity left ample room for the darkness to seep in and swallow me away. After a few desperate weeks, I eventually found that reading fiction – filling my head with another world that left room for little else – was the one thing that made it more bearable to exist. My best friend then suggested (after having gently and generously recommended the book to me for years) that perhaps this was the moment to read Infinite Jest. I think every day about how grateful I am that he did.

I started reading and it soon became the case that so long as Infinite Jest was in my hands, it was possible, okay even, for me to stick around. The core themes of the book that would soothe and sustain me over the coming weeks can be conveyed, I think, by its two dominant and contrasting venues – a halfway house for addicts in recovery on the one hand, and an elite and high-pressure tennis academy on the other – in conjunction with an underlying and unifying thesis: all of us, whether we’re chasing substances, achievements or whatever else we hope will satisfy us and make it bearable to exist, are afflicted. We are all, for lack of a better word, fucked in the head in the very same ways.

With Infinite Jest in my hands, I was suspended afloat by a contradictory catharsis, this evanescent insight that I could hold on to so long as I just kept reading and rereading the book’s (blessedly many) pages: that I was not crazy, nor alone, precisely because I really was crazy, which is to say that this all wasn’t me but rather it – it was a human condition. The book assured me that this was just what it was like to be crazy in this way, was exactly how others crazy in the same way were made to feel, a crazy that made them feel just as alone as I now felt. The book witnessed me, affirmed me, and assured me that my experience was familiar to the world. I can’t put it any better than just saying the book was my friend.

The book’s most famous lines are on suicidality, and the air-tight logic that it brings along

Some passages can only speak for themselves, as they so articulate (and help me remember) facets of the thing I was facing on that sofa. On the ‘psychotic depression’ suffered by the character Kate Gompert, the most haunting and compelling personification of depression I have come across:

It is a level of psychic pain wholly incompatible with human life as we know it. It is a sense of radical and thoroughgoing evil not just as a feature but as the essence of conscious existence. It is a sense of poisoning that pervades the self at the self’s most elementary levels. It is a nausea of the cells and soul … It … is probably mostly indescribable except as a sort of double bind in which any/all of the alternatives we associate with human agency – sitting or standing, doing or resting, speaking or keeping silent, living or dying – are not just unpleasant but literally horrible.

No description that I’ve encountered has better conveyed, so clearly and directly, the precise nature of that moment-by-moment agony in which I had found myself.

Infinite Jest’s most famous lines are on suicidality, and the air-tight logic that it brings along. The book analogises it to the choice faced by those trapped inside a burning building and deciding whether to jump:

Make no mistake about people who leap from burning windows. Their terror of falling from a great height is still just as great as it would be for you or me standing speculatively at the same window just checking out the view; ie, the fear of falling remains a constant … It’s not desiring the fall; it’s terror of the flames. And yet nobody down on the sidewalk, looking up and yelling ‘Don’t!’ and ‘Hang on!’, can understand the jump. Not really. You’d have to have personally been trapped and felt flames to really understand a terror way beyond falling.

The suicidal person, in other words, is not misguided but rather literally facing different choices – ones unimaginable to those who do not also have flames slowly engulfing them.

I don’t think I can really explain what reading all this meant to me. The book could see me like a mirror at that moment and describe it all right back. More concretely, I can’t explain what it meant to find such forceful validations of my particular sense of this ‘mental illness’, not as some wrong or irrational reaction by me, a misapprehension or miscalculation on my part, but rather as something happening to me; it was a thing inside me – a billowing shape, as the book often calls it – to which all my dread and despair was actually just the reasonable and appropriate response. But I can tell you that, once I finished Infinite Jest, my grip on this self-understanding – and so my self-preservation – quickly started to slip away, and it was only a few days later that I tried to kill myself. By then, I was back to being alone on that sofa, surrounded by those flames the book had managed to keep at bay. I think reading Infinite Jest had been keeping me alive.

So that’s why, when he came to the hospital, my friend knew to bring along another copy of the book. I remember looking up at him then, bleary-eyed with anxious shame for what felt like my most monumental failure, a profoundly self-absorbed act of weakness on my part – and, not to mention, a terrible inconvenience for all those I’d dared to drag into my life. He smiled softly while waving Infinite Jest in a silent reminder that these emotions, though compelling in their presentation and thus reasonable to be so compelled by, weren’t really reflecting the reality of the matter. And with a copy to share, in that secured visiting area, we then had our own little pop-up book club.

I admit to sometimes feeling guilty for being the one who found salvation in his book instead of him

It all felt a bit like Bible study or something, in the fluorescent sterility and chaos of that strange space, and I remember my friend making some fittingly dark joke about how this was probably how DFW would’ve most wanted the book to be read anyway: like the word of God, among rock bottoms, being involuntarily held. It was a glimmer of Wallace’s raw hilarity, which fills so much of Infinite Jest (1996) – a grotesque humour, one that could punctuate my otherwise continuously unbearable tenure on that sofa with stitches of transcendent laughter, and which not only kept me alive but sometimes feeling alive, wanting to be, hoping I do somehow make it through it all, if for no other reason than because laughing still felt like something worthwhile. I was reminded, in our pop-up book club, that maybe this was still worth doing. In truth, the reality of what had happened was only beginning to crash down upon me, and it was going to be a very long road ahead. But we at least managed to make it all a bit gentler and more intelligible in that moment.

As of this September, it has been 15 years since Wallace’s suicide and two and a half years since my attempt. Like Wallace’s, my own decision to take my life had immediately followed an adjustment to my antidepressants. I remember it clearly: I’d been holding on so long as I’d still been reading, and when the reading was over and the enkindling darkness took its place, there was just barely enough left in me to pull myself up and pick up a phone, to articulate the necessary words and ask the professionals if they could possibly find some way to help me out. I’d still been searching in anguish for an escape as the walls closed in, a way to still win, to stick around.

Sadly, it was the prescribed dosage increase itself that hit me – as it is sometimes known to do – with another dark wave, knocking me back into the depths of myself, right as I’d been treading so very hard to reach a stable surface. I know Wallace’s suicide had been amid choppy chemical changes of his own, which is to say that we’d both still been fighting, and so these disparate outcomes were the product of random chance. There is a tragedy and humanity, I think, for one’s own desperate attempt at staying alive to be the very thing that does one in – and I admit to sometimes feeling guilty for being the one who found salvation in his book instead of him, as though this salvation was itself cosmically predestined to be scarce.

When I’m asked what exactly I found in Infinite Jest, I limit myself to noting two things. I found powerful portraits of mental illness, and I also found empathy. Like I said, the book was my friend. But the thing is, I know that many others have very different things to say about Infinite Jest – about the book, its author, its ‘prototypical’ readers, the very idea of it, and the ethos it has come to represent. In her chapter ‘On Not Reading DFW’ (2016), Amy Hungerford defends her choice never to read it by arguing (among other things) that there’s no reason to think DFW could have anything valuable to say about women. More recently, in the London Review of Books this July, Patricia Lockwood said of Infinite Jest that ‘it’s like watching someone undergo the latest possible puberty. It genuinely reads like he has not had sex.’

Hungerford, Lockwood and the mainstream ethos generally dismiss the book’s intended and actual audiences as white, male and not to be trusted, driven by Stockholm syndrome, sunk costs or delusions of self-interested grandeur in calling the book genius or important. I’m not exaggerating when I say that I find these critiques – so often snide or irreverent in their cadence – baffling, gaslighting, disempowering, at times even agonising. I can’t understand what they could possibly have to do with this book that I know as my friend, that I found myself in at my most alienated moment. And the bitter irony is that this ethos all concerns a man who, after writing such an empathetic book about mental illness, took his own life; for it is a collective instance of the very kind of empathy failure that I think Infinite Jest asks us to resist and helped me resist myself. I guess it is the least I can do for it now – and for my own survivor’s guilt – to join this ongoing chorus on the book with my own belting, discordant voice.

Mental illness can persuade you that you’re now seeing the reality that had always been real

Infinite Jest was life-saving for me, but I don’t just mean when I say this that it had been saving me while I was reading it on that sofa, or even the times that I’ve read the book since. Infinite Jest is saving my life all the time. There’s a recurring motif in the book, a haunting symbol for all of our many mental demons: the Face in the Floor. It first appears in a second-person vignette as an evil presence that only you, the reader, can feel. You wake up from a nightmare, you look around, and you suddenly notice that there is the Face in the Floor beneath you. It is a Face that you know is evil, and you know this evil is only for you. But as soon as you notice this Face in the Floor, you are also convinced that it has actually been there all along. You are certain of this, that its ‘horrid toothy smile [has been] leering right at your light all the time,’ and that it had simply been ‘unfelt by all others and unseen by you’ until now. In a later passage, this evil Face in the Floor – ‘the grinning root-white face of your worst nightmares’ – comes back, but this time, it’s your addiction. It ‘finally remove[s] its smily-face mask to reveal centerless eyes’, and you see that the Face in the Floor – your addiction – has now completely taken you over. The Face in the Floor has become your own. It’s ‘your own face in the mirror, now, it’s you’ for it has ‘devoured or replaced and become you’.

I think about the Face in the Floor every single day. I remind myself of it. One of the most harrowing things about mental illness is not anything captured by descriptions of its first-order symptoms, but rather the way it can convince you that these symptoms are just picking up on something that is and has always been the case, that was actually there all the time; and when you didn’t feel this way it was because you had been blind. Mental illness can persuade you that you’re now seeing the reality that had always been real, the Face that had always been there in the Floor – which is all to say that your epistemic position has simply been improved. So long as that is what you are being made to believe, then how can anyone expect you to also believe ‘this too shall pass’ (or anything of the sort), or to somehow just stop it from swallowing you up?

I’m no longer on that sofa or surrounded by those flames. But still, I’ll probably always be moving with and managing my own billowing shape. Mine is a synergistic and explosive Molotov cocktail of depression and ‘emotion dysregulation’. This basically means that my internal reality is prone to quickly and intensely turn itself upside down again and again – somersaulting through euphoria, despair, mania, shame, rage, paranoia, guilt, panic, bliss, self-aggrandizement, self-hatred, even within a single day. My challenge in the dissociated midst of these episodes will always be to find something from outside the moment to believe in, or to at least have faith that any such thing could even exist, and so to resist the recurring immersive insistence that only this moment and nothing before it is what’s real.

Maybe that’s why I needed to say all of this, to give my experience this reality and write it all down, and paper over at least one of the Floor’s Faces and preserve this here instead for myself; and maybe these revelations are also my redemption for that audacity to have been the one saved. But when I say that Infinite Jest is saving my life all the time, what I mean is that I still keep trying my very best to tell myself – because I still need and will keep needing to tell myself – what has become both my mantra and my prayer: it’s the Face in the Floor. It’s the Face in the Floor. It’s the Face in the Floor.

In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. Or text HOME to 741741 to reach Crisis Text Line.

In the UK and Ireland, the Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie

In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14

Other international helplines can be found at www.befrienders.org