We’d be outraged if a business owner told an employee she wouldn’t receive her bonus unless she lost weight. With most jobs, our looks should be regarded as irrelevant to our suitability and remuneration. What matters is that we have the skills for the job and put them to good use. Yet appearance discrimination, or ‘lookism’, is pervasive and consequential in the workplace. Can lookism in employment ever be justified? And, when it can’t, should we legislate against it?

The first of these questions might seem to have an easy answer, namely, that lookism can be justified only when appearance is a genuine qualification for work, that is, has a real bearing on a person’s ability to do a job or do it well, such as modelling or some acting roles. But this just pushes back the problem. We must now ask: when is appearance a genuine qualification for a job? And even: should genuine qualifications always count, or can there be moral reasons for not counting them?

Much the same questions arise in relation to race and gender. There are cases when each of these can be regarded, reasonably, as a ‘genuine occupational requirement’, for example, ‘being a woman’ for a women’s refuge support worker. But it is equally clear that ‘being a man’ cannot justifiably count as a qualification for being a doctor, even if patients might be happier receiving medical advice from a man because, for sexist reasons, they rate men’s medical skills more highly. And that is so even though there’s a sense in which being a man is a genuine qualification for the job when a male doctor would be better able to minister to patients’ needs because their prejudices mean they’d trust him more and hence be more receptive to his advice. In other words, there are some genuine qualifications that it is not justifiable to count.

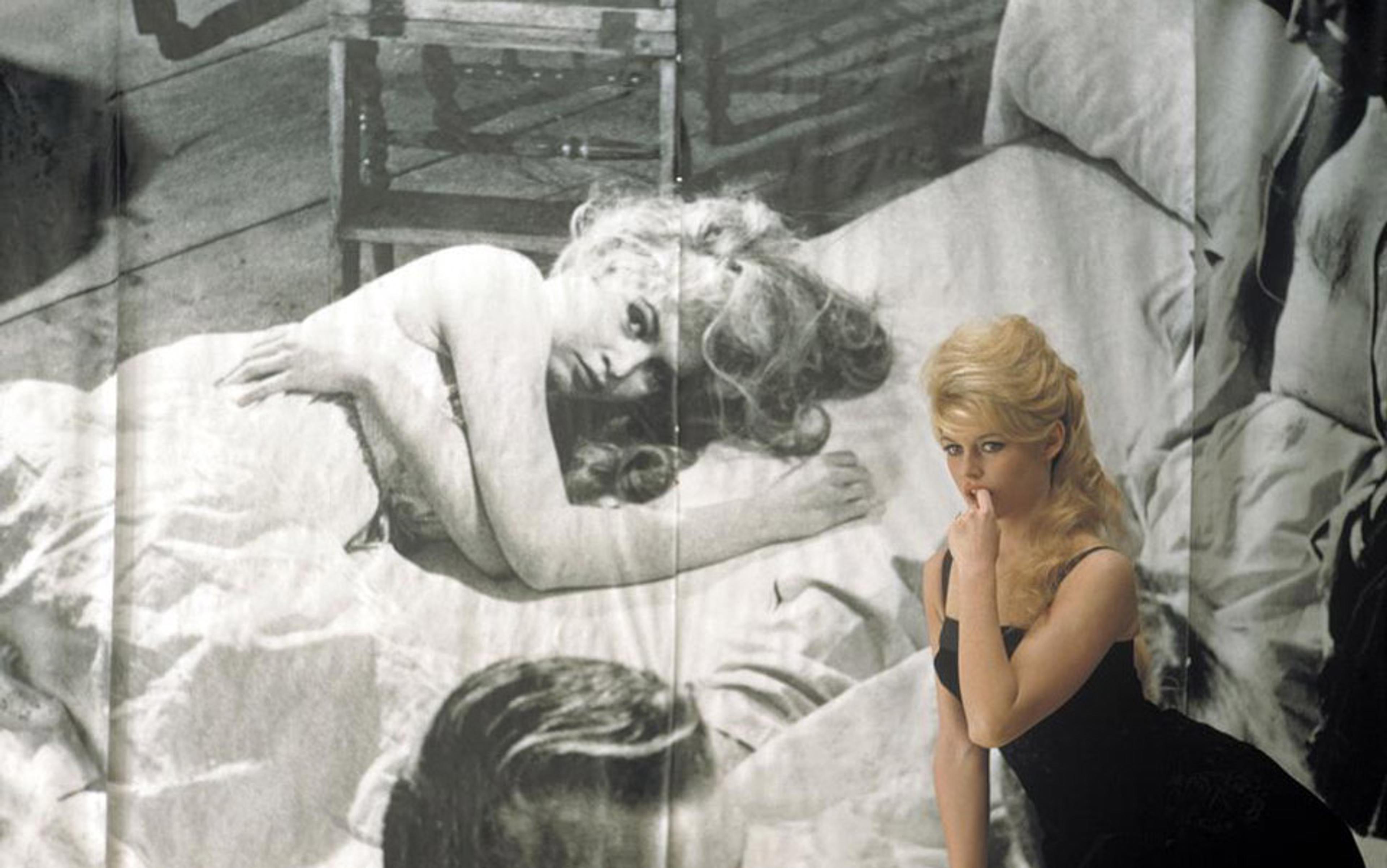

Consider two cases that concern the treatment of employees in the workplace and vividly raise worries about appearance unjustifiably counting as a qualification. The first relates to a performance evaluation of an employee called Courtney at a Canadian fashion company whose manager said her looks were affecting her ability to do her job. Interviewed by the BBC in 2022, Courtney said:

He point-blank told me that he thought I was too fat to be in the position I was in. He told me he was embarrassed having me around our vendors in meetings, and that it ruined his reputation.

He then advised her to start going to the gym and avoid wearing fitted clothing. Unsurprisingly, Courtney felt shell-shocked. Subsequently, her appearance anxieties had a negative impact on her work because she was distracted by worries about what her colleagues thought of her.

Our responses to the looks of others often involve unjustified associations, whether positive or negative

The second case relates to an accusation in 2020 by the UK radio journalist Libby Purves against the BBC. Purves claimed that, for presenters on both television and radio, older women were under greater pressure than men of a similar age to appear younger, since women are judged on their looks, and part of what it is to be attractive for women is to look youthful. In an opinion piece for the Radio Times, she wrote:

Sue Barker has been binned from A Question of Sport after 23 years. She is 64. More willingly, Jenni Murray and Jane Garvey depart from Woman’s Hour, aged 70 and 56. They are replaced by Emma Barnett, a mere 35. What is this? … Are we written off as old trouts while men become revered elders, sacred patriarchs, silver foxes?

In both cases, lookism seems entangled with sex or gender discrimination, and, in the second case, with age discrimination too. This might provoke the thought that appearance discrimination is problematic only when it is entwined with some other form of discrimination, and that there is no reason to be concerned about it when it occurs on its own. But that seems clearly false. Appearance discrimination matters in its own right, and indeed operates in many of the same ways as other forms of discrimination we are committed to fighting, such as racial discrimination. Just as prejudices influence behaviour consciously and non-consciously in racial discrimination, so too they operate in conscious and non-conscious ways in lookism. Our responses to the looks of others often involve unjustified associations, whether positive or negative, between appearance features and character traits. These associations may function as implicit biases, or sometimes take the form of stereotypes that are endorsed with varying degrees of unreflectiveness.

Women especially are often seen as lazy or lacking in self-discipline if they are perceived as overweight. But even though lifestyle choices make a difference to shape, the hunger we experience and how much we weigh are largely determined by metabolism or physiology. So the idea that all or even most people with a heavier weight lack self-control is unsustainable when brought into contact with the evidence. In her book Unshrinking: How to Fight Fatphobia (2024), Kate Manne concludes that ‘fatness has a strong genetic basis … at least 70 per cent of the variance in body mass that we find in the human population is likely due to genetics.’

Of course, it is not just selectors evaluating qualifications who are prone to biases. Good looks tend to be beneficial in doing a range of jobs because of how others respond to them. Viewers may prefer to watch attractive newsreaders deliver the TV news, perhaps in part because they associate their appearance with desirable character traits, such as trustworthiness. Customers may be put off interacting with employees they regard as fat because they find their appearance unattractive or judge them to be ill-disciplined. It’s for reasons of this sort that good looks can be genuine qualifications for working in customer-facing roles, even though there is a further question about whether it’s justifiable to count them.

Qualifications that arise in this way are often referred to as ‘reaction qualifications’, meaning qualifications produced by customer reactions to employee characteristics. As a result, even selectors who do not share the customers’ biases have a reason to appoint people with their customers’ preferred features, and to reject those with features their customers dislike. In contrast, when a technical skill is a qualification for a job, its role as a qualification, and indeed its status as a skill, doesn’t generally rely on others’ reactions to it. All that matters is that it is deployed in making a product that people want or providing a service they need. For example, the skill of giving competent legal advice is a qualification for being a lawyer, regardless of how others respond to it.

In addition to the association between heavier weight and laziness or lack of self-control, people routinely make other appearance-related associations. Short men are often regarded as prickly or prone to aggression on the basis that they have inferiority complexes. Facial scarring, and other so-called ‘facial disfigurements’, are often associated with unpleasantness or nastiness – think of Hollywood villains. Again, these associations don’t stand up against the evidence. When reaction qualifications are rooted in unjustified associations, is it fair to count them? We don’t think it’s morally acceptable to count reaction qualifications when they are grounded in, say, customers’ prejudices against women or members of a particular race, so why think it’s morally acceptable to count such qualifications when they are grounded in customers’ prejudices against particular appearance features?

There’s no getting away from the fact that ignoring customer preferences would be bad for business

Even when they don’t involve prejudices or unjustified associations, customers’ perceptions about whether an assistant is good looking, and indeed the perceptions of job recruiters, are usually a product of ‘internalising’ appearance norms – that is, rules concerning how we should look – that reflect conventional aesthetic preferences. Some of these norms may have gained currency over many generations, as a result of the way that being disposed to act from them when choosing sexual partners bestows evolutionary advantages, as Nancy Etcoff argues in Survival of the Prettiest (2000). Perhaps this is true of norms that favour unblemished skin or symmetrical faces. But other appearance norms expressing aesthetic preferences emerge from practices that are specific to particular cultures, and may even be a product of differences in power and privilege. For example, the emergence of norms regarding tightly coiled hair as messy, or favouring narrow rather than broad noses, or lighter over darker skin tones, can perhaps be fully explained by the way in which they reflect and perpetuate racial hierarchies – that is, they come to be endorsed because they legitimate the power and privilege that accrues to membership in particular racial groups. Even when norms are not the product of power and privilege, their application may end up benefiting people who are already advantaged, and further disadvantaging those who are already disadvantaged. Think here of norms biased against women or the elderly, or both, such as norms that regard youthfulness as part of what it is to be an attractive woman, which Purves thinks are influencing decisions at the BBC.

But there’s no getting away from the fact that ignoring customer preferences would be bad for business. Therefore, reaction qualifications grounded in such preferences provide some credibility to recruitment decisions based on them. In contrast, when selectors but not customers are influenced by looks, then no such justification is available. We don’t know whether vendors were put off by Courtney’s appearance or whether it was only her manager who had a problem with it. But it is surely unfair to candidates when managers’ hiring (or promotion) decisions are influenced by employees’ appearance if it is not even a reaction qualification. Indeed, it is generally unfair to take into account features of a person, whether racial membership or looks, when these have absolutely nothing to do with their ability to do the job.

Prejudices and negative associations concerning various appearance features unfairly reduce the range of career opportunities for people with these features. This then contributes to an unjust distribution of resources, and may even reinforce structural injustices. According to Daniel Hamermesh’s analysis of data from the United States in Beauty Pays (2011), the overall ‘beauty premium’ for above-average-looking women, compared with below-average-looking women, is 12 per cent; for above-average-looking men, compared with below-average-looking men, it is 17 per cent. Perhaps appearance is a legitimate qualification for some jobs, such as modelling, in which case not all such inequalities will be unjust, but often lookism seems analogous to racial discrimination, and condemnable for many of the same reasons.

But there are also cases of lookism that are rather different from racial discrimination because they involve responding to chosen features of appearance, such as tattoos, hairstyles and piercings. It is tempting to say that if a person is disadvantaged by an appearance feature they’ve chosen, in full knowledge that acquiring it will affect their employment prospects, then there is no injustice. But even here, customers may be opposed to such features for no good reason, for example, when tattoos are unjustifiably associated with aggression or mental health problems. Is it fair, in a job market, to disadvantage a person by her choices when that disadvantage reflects the prejudices of selectors or customers responding negatively to features she’s chosen for herself and that may even have become part of her identity?

People may also make choices designed to improve their chances in particular job markets, for example, they may have liposuction, Botox injections or hair transplants, often to appear younger. This is especially so in visual media where, as Purves points out, part of what it is for women to be attractive is to look youthful. It would be easy to describe these interventions as chosen, but we should hesitate before doing so. Decisions to have them are often a product not only of seeking to improve one’s employment opportunities but also body-shaming practices. Indeed, as Heather Widdows argues in Perfect Me (2018), appearance norms form an ethical ideal, with those who fail to comply being regarded as not merely unattractive but morally flawed, because they are seen as failing in their duty to make the best of themselves. This ideal has become so demanding that it is oppressive to many people, especially women and younger men. When jobs are allocated in a way that rewards people who conform to these norms, then they are reinforced, and the pressures to conform to them become even greater.

Appearance features may express deeply held convictions about how one should live

Appearance features that are favoured or disfavoured in the job market may also be chosen by people in a way that reflects their own ethical commitments rather than dominant appearance norms. For example, some women choose not to wear makeup because they want to resist the idea of women as aesthetically appealing objects. As Clare Chambers writes in Intact (2022), they endorse the principle of the unmodified body – that our bodies are alright just as they are. As a resistance to body-shaming practices, people may consciously eschew body modifications and withstand the pressures placed on them by the often vicious comments they receive. Others may be committed to ethical principles derived from their religion requiring conformity to unconventional appearance norms or dress codes.

So appearance features may express deeply held convictions about how one should live. When companies have an ethos that reflects such convictions, and they discriminate in their selection practices to promote that ethos, then that often seems unobjectionable. Suppose, for example, that a company has an ethos that reflects a commitment to not wearing makeup, and requires their employees to adopt ‘a natural look’ as a condition of employment. That does not seem morally problematic in the context of a society where there is an expectation in a wide range of jobs that women should wear makeup. Yet in other cases, appearance codes may discriminate against members of a particular religion, even if they do so unintentionally. For example, a dress code forbidding employees from wearing head coverings seems morally problematic because of the way in which it disadvantages Muslim women.

Lookism in employment is therefore a mixed bag. Some cases seem to involve the same characteristic mechanisms as racial discrimination, including prejudices influencing hiring decisions, to be morally condemned for much the same reasons. Other cases seem rather different. They may differ because the appearance-related values that companies express in their hiring practices neither reflect prejudices nor deny the fundamental equality of different people. Or they may differ because the appearance features that recruiters count as reaction qualifications are unobjectionable, perhaps in part because these features are genuinely a matter of choice for job applicants.

In cases where lookism is morally problematic, what should we do about it? Should we think of it as posing a moral problem of sufficient magnitude that there is a case for seeking to prevent it by legislation? Or is it better to tackle it without recourse to the legal system? There is evidence that lookism in employment is comparable in pervasiveness and harmfulness with other forms of discrimination, including racial discrimination. On the basis of his analysis of the data, Hamermesh maintains that, in the US:

African American men’s earnings disadvantage, adjusted for the earnings-enhancing characteristics that they bring to labour markets, is similar to the disadvantage experienced by below-average compared to above-average-looking male workers generally.

Of course, there are differences between racial discrimination and appearance discrimination that may impact upon the case for enacting legislation to prevent it, and not merely the fact that (unlike race) some appearance features are chosen. Racial membership is commonly transmitted from one generation to another, whereas the inheritance of appearance-related characteristics is less reliable. The way in which racial discrimination contributes to and reproduces structural disadvantages through practices of segregation gives rise to distinctive problems in tackling it. Nevertheless, some of the same reasons that provide a strong case for prohibiting racial discrimination also apply to appearance discrimination.

The long-term solution to the injustices of lookism involves taking measures to reduce the enormous weight ordinarily placed on appearance in our society and seeking to change appearance norms so that they become more inclusive. But given the magnitude of the problem, we should take seriously the idea that legislation also has role to play. Should we make ‘appearance’ or appearance features such as height, weight and facial differences protected characteristics, in the same way that, in countries like the UK, race, sex, sexual orientation, disability, religion and age are ‘protected characteristics’, meaning it is illegal to discriminate on their basis?

The legislation itself wouldn’t require us to make objective judgments about people’s attractiveness

Perhaps legislation against ‘indirect’ discrimination, that is, against policies and practices that unintentionally affect people with a protected characteristic in a negative way, is enough to criminalise much appearance discrimination in hiring and promotion decisions, providing an underutilised way of combatting it. Suppose that appearance norms and dress codes are biased against people with tightly coiled hair, or with darker skin tones, or with asymmetrical faces or bodies, or with wrinkly skin, or against those who see it as part of their religious duty to dress modestly, or against women who object to being required to wear makeup or heels. Then selecting people on the basis of their conformity to these norms (or their willingness to conform to them) will stand in need of justification in any legislative scheme that requires indirect discrimination on grounds of race, sex, disability, age or religion to be a proportionate means to a legitimate goal. But it is not clear that legislation against indirect discrimination is enough to deal adequately with the moral challenge posed by lookism in employment.

My proposal would be this: we make it illegal to reject a person on the basis of their appearance, or particular appearance-related features, when no plausible case can be made that these features are qualifications for the job in question – when possession of them can’t even be seen as a way of conforming to a company’s ethos or attracting its customers or clients. We could add to this the requirement that reaction qualifications, that is, qualifications that rely on the responses of customers, shouldn’t be given any weight if they rest upon customers’ prejudices about an appearance feature, where prejudices are generalisations or associations that aren’t sustained by the publicly available evidence. And we could make it a presumption that when the background culture is infused with these prejudices about a particular appearance feature, then reaction qualifications related to that feature should be regarded as illegitimate, unless evidence can be produced for thinking that customer preferences for it are unconnected to such prejudices.

Some may be sceptical about whether legislation against lookism could be effective, with good reasons. Part of the problem with legislation in this area is that there is likely to be resistance to making use of it – who wants to admit that others regard them as unattractive? Furthermore, appearance discrimination can be hard to detect and monitor. The legislation itself wouldn’t require us to make objective judgments about people’s attractiveness. We just have to know that selectors have been influenced by the candidates’ appearance, or by the particular appearance features they possess, when these have nothing to do with their ability to do the job. But we do need to be able to monitor different companies to see whether there is any reason to think that they aren’t complying with the legislation. With race and gender, we can examine percentages in the workforce or selected through the appointment process. But how can we do that in relation to an attractive appearance?

There is a surprisingly large amount of intersubjective agreement concerning judgments of attractiveness, and it may well be enough to collect the data required for monitoring purposes. So I think that the objections to legislation against appearance discrimination are not insuperable. It is feasible, and no less desirable than other forms of antidiscrimination legislation. But perhaps the main function of legislation against appearance discrimination would be to send out a message to employers, and society more generally, that lookism is unacceptable, and to give companies a reason to examine their practices and reform them if they encourage lookism or give it too much space in which to operate. We might even regard it as good practice for recruitment interviewees to be behind a screen, as is sometimes done when auditioning musicians. In the context of employment at least, we should combat what Francesca Minerva calls the ‘invisible discrimination’ that takes place right before our eyes. We’ve been too complacent about lookism at the workplace for too long.