The 19th-century Middle East presents a paradox. On the one hand, this was a time when the idea of a modern, secular society became possible. On the other, it saw the rise of newly divisive religious identities that stood opposed to that idea. Across the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire, intellectuals were creating a modern public sphere: a vibrant periodical press, a series of cultural associations and new-style schools. Adherents of different religions – Muslims, Christians, Jews – rubbed shoulders in these institutions, debating society, science and culture. A few – like the ‘materialist’ Shibli Shumayyil – began to recommend modern science as an alternative to religion. The Ottoman state, meanwhile, proclaimed the formal equality of its subjects of different religions, in 1856. Many intellectuals took it at its word, appealing to their fellows to set aside religious differences in the name of a ‘homeland’ or ‘nation’ for people of all faiths.

At the same time, these Arab provinces – notably Syria and Lebanon – were racked with major conflicts between religious communities. In Lebanon, the 1840s and ’50s saw bitter fighting between armed groups from the Druze Abrahamic and Maronite Christian communities. Tensions rose across Syria, fuelled by the intervention of European states and fears of their growing power within the Ottoman lands. In 1860, these pressures came to a head: in the provincial capital of Damascus itself, a crowd of armed Muslims massacred several thousand Christians. Meanwhile, religious leaders and revivalists were seeking to create more homogeneous religious communities, clearly distinct from one another. Muslim activists of the early Salafi movement, like Rashid Rida, advocated a return to the pure example of the Prophet Muhammad’s time. Catholic clerics like Patriarch Maximus Mazlum aimed to mark off their communities unambiguously from other Christian groups as well as Muslims. These projects were, in their way, as modern as those of secularity or scientific rationalism. They set out to eradicate an older set of religious practices – like the common worship of saints and shrines, or shared processions and holy days – that had at times blurred the boundaries between faiths.

The 19th century in the Arab-Ottoman world has thus left a contradictory legacy. It saw the emergence of two kinds of project that would go on to divide the Middle East, until today: ones aiming at a secular society, science and rationalism on the one hand, and ones insisting on religious identity and the separateness of religious communities on the other. How did these tendencies – so contradictory on the surface – come into being in the same moment, side by side?

Mikha’il Mishaqa in Damascus, Syria in 1859. Courtesy Wikipedia

One way of answering this question is through a microhistory: by looking at the story of one individual who played a part in the emergence of both kinds of project. Such a person was Mikha’il Mishaqa, a man who helped to shape both scientific rationalism and religious revival, as he followed his own eccentric path through the Arab 19th century. The story of his unusual journey through doubt to faith illuminates a shift taking place in the place of religion in Arab-Ottoman society: one that helps us see how the roots of rational secularism and of divisive religious identity were intertwined.

Mishaqa arrived in the Egyptian port of Damietta in 1817, aged 17. In the bustling city, the main hub for trade between Syria and Egypt, he found a world very different from the Lebanese mountain town, Dayr al-Qamar, where he had grown up. Along the Nile frontage, barges unloaded coffee, rice or linens directly into the waterfront entrances of houses and caravanserais. Passing through the port came peasants from Palestine and imams from Istanbul; Jews from Rhodes, and Egyptian Coptic Christians on pilgrimage to Jerusalem. At the heart of the city’s trade was the small but wealthy community of Christian merchants from Syria: the young Mikha’il took his place among them, lodging with his uncle and elder brother who were already established in Damietta, and set out to learn the business and make money.

But there was a fly in the ointment. Each spring, the plague appeared in town. At its height, up to 100 funeral processions could be seen leaving the city. And the disease regularly continued infecting and killing Damietta’s inhabitants for several months, into June or July. It presented a problem for everyone: but there was no consensus on how to deal with it. Many, both Muslims and Christians, resorted to prayer; some to magical means, like drawing squares or diagrams on the outside of rooms and houses as protection. Others (or the same people) looked to medical means – but doctors disagreed on the plague’s true causes and treatment. Some thought it spread by touch, others by breathing foul air; some thought tobacco smoke or laudanum useful protections, others dismissed these remedies. Damietta’s wealthy Christians sought to preserve themselves by a form of ‘lockdown’, shutting themselves in their houses or apartments for several months, and washing all goods that entered in water or vinegar.

These different reactions could cause disputes: adopting elaborate medical precautions could seem to deny God’s power, while relying on magic or prayer alone could seem dangerously careless. In the mixed society of the busy Egyptian port, different belief-systems rubbed up against each other as all confronted the shared challenge of plague. Soon after Mikha’il Mishaqa arrived in Damietta, his elder brother Andrawus caught the plague, but recovered. Above the door of his room, though, Mikha’il found papers bearing a religious slogan, placed there by the local Catholic priest. These, he was informed, were supposed to ‘stop the plague entering the place’: but, as Mikha’il remarked, they had clearly failed, because Andrawus had caught the plague anyway. ‘Don’t be of little religion and sow doubts,’ he was told. Yet the doubt persisted: these contradictions in dealing with the plague were one factor leading Mishaqa to doubt religion as such.

‘I came to reckon everything I read and heard in the books of the sects as falsehoods and delusions of utter futility’

The other major factor also had its roots in the unusually varied social mix of Damietta. For more than a decade, the richest Christian merchant of the city, Basili Fakhr – in touch with Greek clerics and sailors, and with Western European travellers and scholars – had been sponsoring the translation into Arabic of works of the European Enlightenment. This was the first time that post-Newtonian science, or the sceptical thought of French deists, was available in Arabic. And Mishaqa had already read some of these books at his home in Mount Lebanon, thanks to an uncle who had brought them from Damietta: now he read more. Enlightenment science offered him a system of ‘natural laws’ to explain and predict the phenomena of nature – like the movements of the planets and stars – with mathematical precision. By contrast, the ‘laws’ laid down by religion came to seem doubtful and irrational. The seal was set on Mishaqa’s rejection of religion when he read another of Fakhr’s Arabic translations. This was the Ruins of Empire by the French philosophe Constantin-François de Volney, who had himself travelled through Egypt and Syria in the 1780s.

Volney argued that human affairs – like the natural world – were governed by ‘natural laws, regular in their course, consistent in their effects’. Religions, however, were mystifications of these laws, derived from misunderstandings of the cosmos, and perpetuated by priestly elites who sought to maintain their own power. As Mishaqa would later put it: ‘I [came] to think that all religions were lies, and that the religious laws had been created by the wise, as a bridle for the ignorant.’ Like Volney, Mishaqa did not reject the notion of a divine being, who had created the wonders of nature, but resolved to act ‘according to the guidance of the natural light’ that God had ‘planted within us’. Though remaining outwardly a Catholic, so as not to cause scandal to his family and coreligionists, he ‘came to reckon everything I read and heard in the books of the sects as falsehoods and delusions of utter futility’, unacceptable to ‘sound reason’.

While Mishaqa – and, around him, a small circle of young Syrian Catholic men, like his brother Andrawus – was drawn to a deist position based on ‘natural law’ and reason, others in Damietta set out to counter them. The learned Catholic priest Saba Katib wrote a set of essays aimed to refute the ‘heresies’ of materialists both ancient (like Democritus and Epicurus) and modern (like Voltaire and Hobbes). Against them, he made the well-known argument from design: the wondrous universe revealed by science must surely have a divine Creator. And, significantly, Katib adopted a style of argument that was then unusual in Christian apologetics: since his adversaries ‘do not believe in any Scripture, nor in the sending of a Prophet,’ he wrote, ‘I have made the basic issue in the controversy the proof of reason alone.’ Like his deist or atheist adversaries, that is, Katib adopted ‘reason’ – not Biblical texts or ecclesiastical traditions – as his criterion.

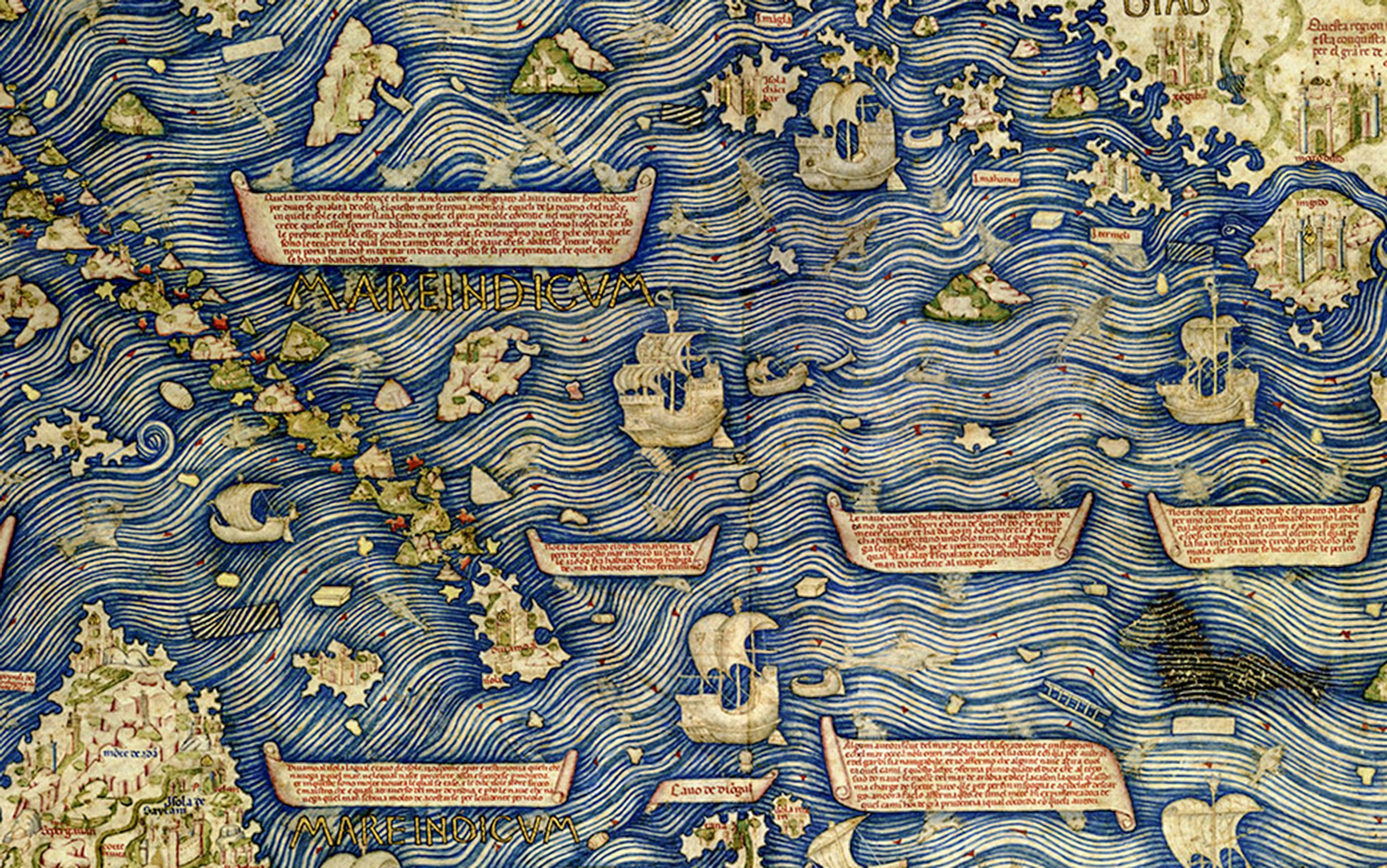

Map of the Emirate of Mount Lebanon, 1752. Courtesy Wikipedia

Mishaqa returned to Mount Lebanon in 1820 – fed up of the plague and lockdowns that ‘imprisoned [me] in [my] house for around five months’ of each year. Building on his family’s role as merchants and bankers to the emir of Mount Lebanon Bashir al-Shihabi, Mishaqa soon found himself near the centres of local political power. Still in his 20s, he was appointed chancellor to the emirs of Hasbaya, a town in the Anti-Lebanon mountains, and granted the rents from extensive lands. He continued his self-education, studying medicine after a brief illness, and writing an innovative treatise on Arab music. He maintained his scepticism about religion: he records in his memoirs several incidents where he poked fun at the pretensions of clerics, Christian and Muslim. This, too, was his attitude when he first encountered, in 1823, a new kind of religious figure: Jonas King, one of the American Protestant missionaries who had recently arrived in Syria. Hearing the ‘handsome’ young New Englander dispute with Catholics in Dayr al-Qamar, Mishaqa ‘laughed secretly at both sides’.

The Evangelical missionaries brought to Ottoman Syria a heavy dose of Western condescension: they regarded its inhabitants as generally ‘uncivilised’ and ‘ignorant’, in need of their own brand of religious enlightenment. But they also brought an unusual interest in the individual beliefs of people they encountered. As they proceeded around the eastern Mediterranean, they reported meeting – in addition to believing Muslims, Jews and local Christians – what they described as ‘infidels’, individuals apparently unconvinced of any of the faiths on offer. They included a Maltese architect, who cited Volney as authority for his belief that ‘the Bible is an imposture’; the deist Dr Marpurgo, a leading Jewish physician of Alexandria; and the Armenian monk Jacob Gregory Wortabet, whom they succeeded in weaning away from his ‘infidel and deistical opinions’ and converting to Protestantism. As the American missionaries embedded themselves in the towns of Syria from the 1830s to the 1850s, they found similar groups, often of young Christian men, dissatisfied with their local churches and rapidly becoming ‘entirely sceptical on the subject of religion’.

To convince these groups of the merits of religion and of Protestant Christianity, the Protestant missionaries drew on rationalistic themes in their own heritage. As the American Pliny Fisk put it in 1823, true Christianity – that is, Evangelical Protestantism – could be seen as a ‘golden medium’ between ‘the two extremes of superstition and infidelity’: between the beliefs of local Christians, Muslims and others, and deism or scepticism. To convince local Christians – particularly Catholics – they often took aim in their preaching and writing at what they saw as irrational aspects of their beliefs: the worship of saints and images, the transubstantiation of bread and wine into Christ’s flesh and blood. And to convince sceptical ‘infidels’, they stressed what they saw as the ‘evidences’ for the truth of Christianity. Much like the Catholic Saba Katib in the 1810s, they based their appeal to such people not on Scripture or tradition, but on ‘reason’.

‘Reason’ continued to be his watchword: yet he no longer believed in reason unaided and alone

It was in the 1840s that Mishaqa felt the force of this appeal. By now, he was living in Damascus, married and prospering as a moneylender, doctor and merchant. He had witnessed dramatic changes in Syria: its occupation by the army of the powerful governor of Egypt, Mehmed Ali Pasha, and the first stirrings of sectarian violence that followed this army’s withdrawal, in 1841. Already swayed by a range of social and intellectual factors to look again for religious truth, in 1842 or 1843 Mishaqa came across a book translated into Arabic by the Protestant missionaries in Malta, called Evidence of Prophecy. In this Evangelical bestseller, the Scottish Presbyterian minister Alexander Keith had set out to prove that the prophecies made in the Bible had in fact come true – thus proving that the text must be divinely inspired. To this end, he compared the Scripture with modern European travellers to the Holy Land, piling up ‘evidence’ of the annihilation of cities that God had said would be destroyed. He even cited the travel narrative of the deist Volney in support of his claims. And to drive home his point, he accompanied the book with engravings – and later, photographs – giving empirical proof of the ruins of Petra, Nimrod or Babylon.

Mishaqa, after some thought and hesitation, found Keith’s arguments convincing, thanks especially to his rationalistic style, so different to that of ‘the doctors of my Church’, with their talk of ‘matters which … sound reasons reject’. A few years later, after further hesitations, and after growing closer to the American Protestant missionaries in Beirut, to other Syrians who had themselves become Protestants, and to the British consul in Damascus, Mishaqa took the irrevocable step of public conversion. In November 1848, he announced his belief ‘in the Christian faith according to the Holy Scriptures’ and was soon embroiled in a bitter controversy with the local head of the religion he was leaving, Maximus Mazlum, patriarch of the Greek Catholic Church. In his arguments against Catholicism – which the Protestant missionaries printed for him in Beirut – Mishaqa denounced the irrational ‘superstitions’ and ‘priestly inventions’ of Catholic doctrine, in similar terms to those he had used of religion in general in his deist youth. ‘Reason’ continued to be his watchword: yet he no longer believed in reason unaided and alone. He now accepted divine revelation as a surer guide, pointing out that rational judgments are often changeable and uncertain.

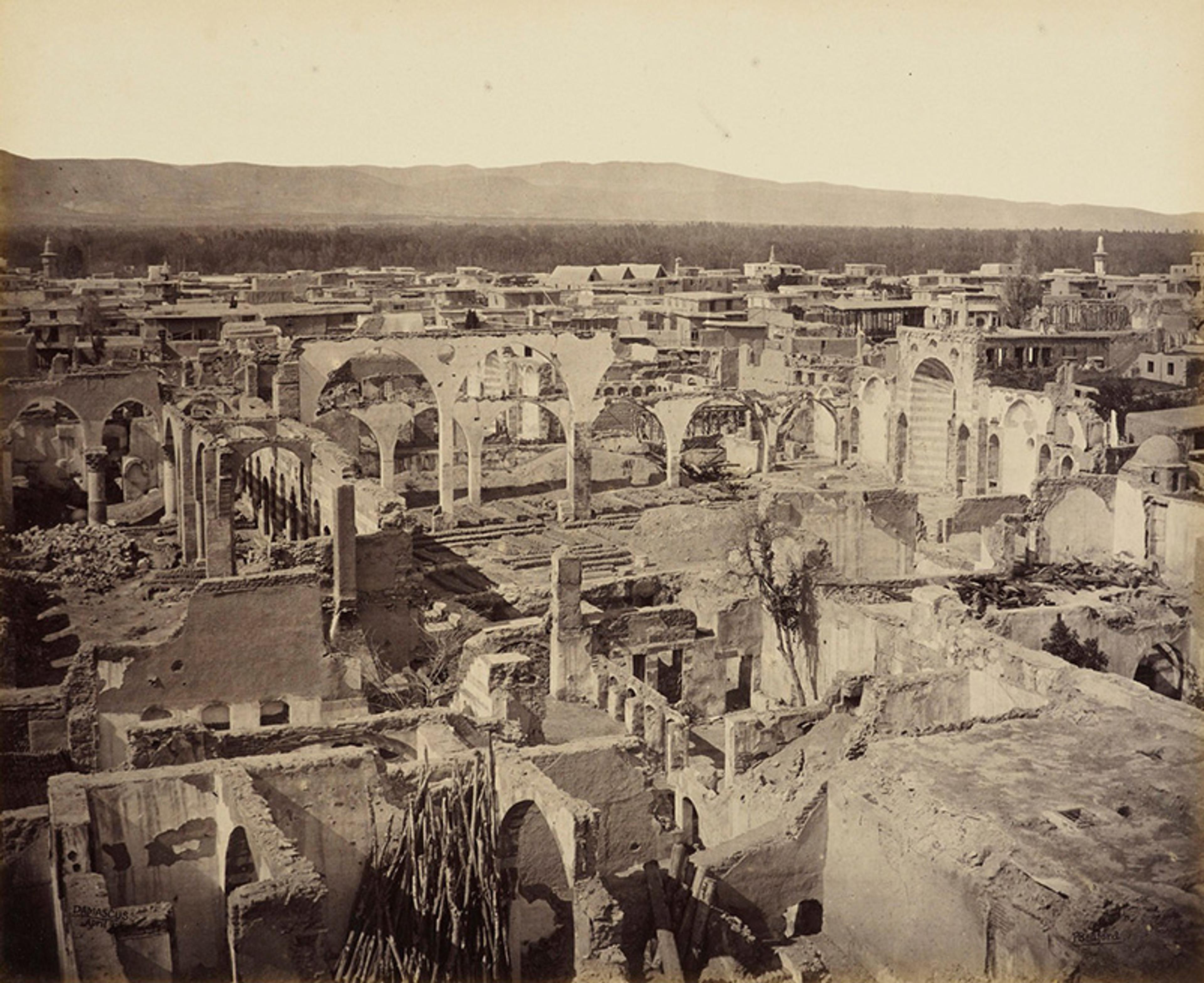

Ruins of a Greek church in the Christian quarter of Damascus, Syria, 30 April 1862. Photo by Francis Bedford, courtesy the Royal Collection, London

This rational Christianity sustained Mishaqa for the remainder of his life, through further upheavals. In 1860, along with other Christians of Damascus, he was attacked by a Muslim crowd in a bloody episode of sectarian violence. He fled through the streets with his two young children: badly beaten, he was lucky to escape with his life. He was able, though, to re-establish himself in Damascus as a prosperous man of business and vice-consul for the United States, positions he passed on to his sons. He kept up a reputation for learning across a broad range, from mathematics to music, and wrote a shrewd and vivid memoir of his life and times, before his death in 1888.

Mishaqa had certainly contributed to creating a modern public sphere in Arabic, and to the cause of scientific rationality. He was an early member of scientific and cultural associations in Ottoman Syria, and wrote for their publications and the growing periodical press. His religious writings, addressed to a public of many faiths, pioneered the use of printed pamphlets in public controversy. And his rationalism could have a sharp edge, as when he denounced popular beliefs and customs, as well as religious practices, as ‘superstitions’.

Yet Mishaqa was also a religious activist. Alongside the American missionaries, he sought to create an Arab form of Evangelical Christianity. His anti-Catholic polemics did much to shape the small but influential Syrian Protestant community, presenting Evangelical doctrines in a form suitable to an Arabic-reading public: the missionaries would reprint them well into the 20th century. They entered a tradition of inter-religious controversy, being picked up by Muslim as well as Catholic apologists. As a result of this, digital copies of these 19th-century texts can now be found on websites devoted to propagating Islam: eg, Quran For All and the Comprehensive Muslim e-Library.

One theme runs through these apparently disparate aspects of Mishaqa’s work and legacy: his insistence on ‘reason’. For him, this was the standard by which any belief should be justified – whether a scientific theory that could be tested by experiment, or a faith in divine revelation that surpassed human understanding. And this had apparently contradictory consequences. Mishaqa could entertain the possibility of being without religion entirely – he had, after all, spent 25 years as a deist – and judge different beliefs from outside, by the light of reason. But then, having opted for a particular faith, he had to insist on its rational credentials, dissociating it sharply from irrational ‘superstition’ and drawing its boundaries more tightly.

The poles of secularism and religious revivalism continue to animate cultural discourse in the Arab world today

And Mishaqa was not alone, in 19th-century Syria, in adopting the post-Enlightenment view of religion as something to be justified by reason, or of the true faith as a ‘golden medium’ between ‘superstition’ and unbelief. Even the Catholic reformer Maximus Mazlum had written a defence of Church doctrine against a Muslim scholar of Al-Azhar University in Cairo, in which he appealed not to Scripture or tradition but to ‘rational, philosophical proofs’. In the decades following Mishaqa’s death in 1888, this way of arguing about religion became increasingly common in the growing Arabic public sphere. Christians, Muslims and scientific ‘materialists’ alike now debated the relationship between faith and reason: and all were coming to assume, like Mishaqa, that they had to place themselves somewhere on a spectrum between unthinking faith and godless reason.

But these same reformers were also emphasising the boundaries between religious communities and practices. Muslim and Christian reformists – the early Salafi movement, Protestant missionaries, and reforming Catholics like Mazlum – set about denouncing the ‘superstitions’ of the common people. Some of these practices blurred the lines between religious communities, as Muslims or Druze visited the shrine of a Christian saint, or vice versa. Others blended religion and magic, or, like popular Sufi gatherings, offended the hardening standards of public morality and elitist ‘good taste’. In order to present their faiths as consistent creeds that could be embraced by rational individuals, reformists of all stripes had to strip away these heterodox, vernacular, collective and often syncretic practices. Yet, as they did so, they unpicked the fabric of a shared religious culture: a hierarchical but multifaith order in which Muslims, Christians, Jews and others had found a place. In its stead, they helped to create the contradictory possibilities of modernity: on the one hand, the image of a secular society and public sphere, of coexistence and equality between faiths; on the other, projects of ‘rationalised’, identitarian revival, of exclusive and homogeneous religious communities.

The eccentric figure of Mikha’il Mishaqa reminds us that these contradictory possibilities came out of a shared transition: towards the justification of religious faith in terms of reason, and the stress on individual belief as opposed to collective practice. The two poles of secularism and religious revivalism continue to animate much cultural discourse in the Arab world today. Mishaqa’s story recalls that they are both aspects of the same, modern, reality: that they emerged together, locked into a quarrel that was also a dialogue.