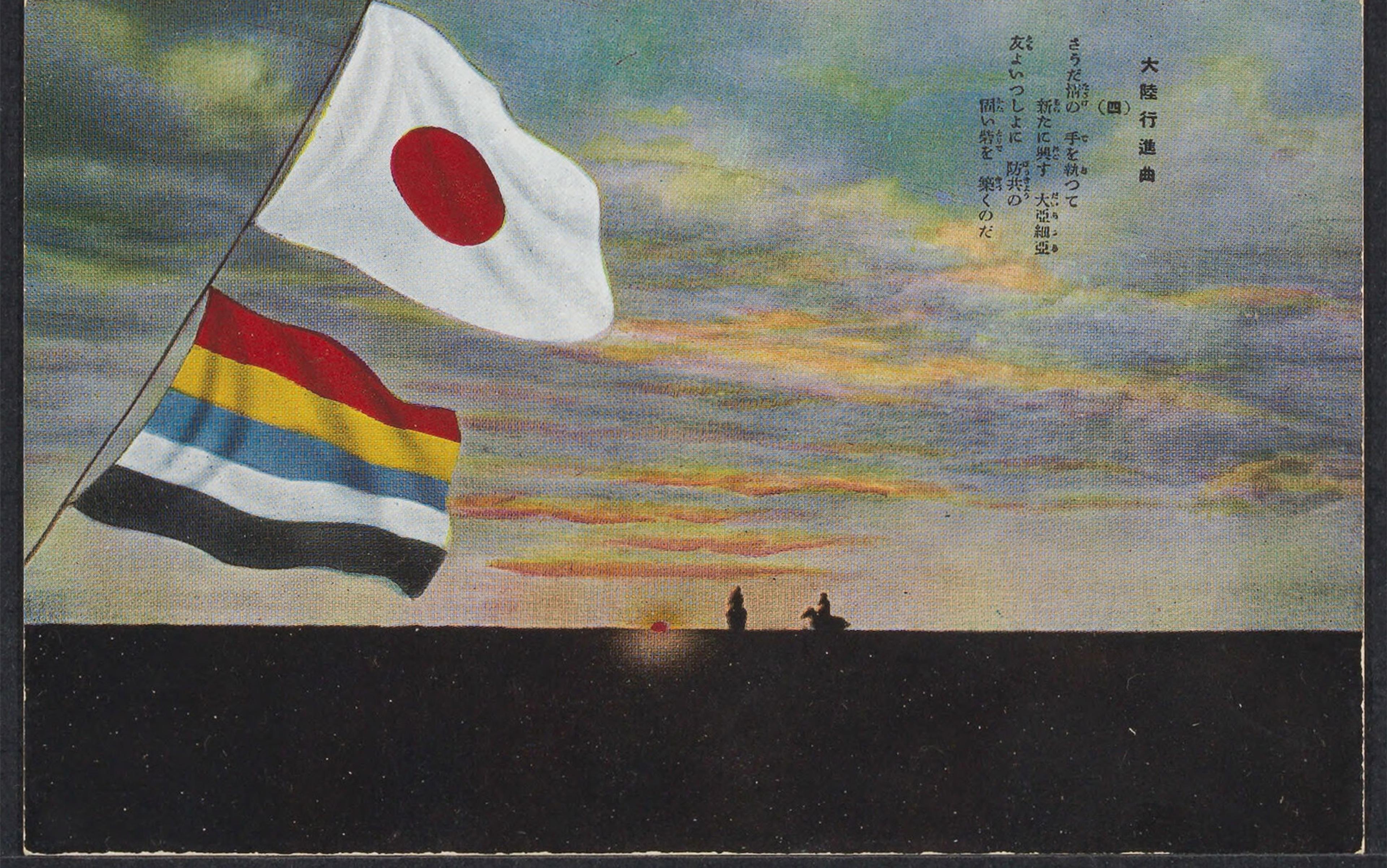

The Arab East was among the last regions in the world to be colonised by Western powers. It was also the first to be colonised in the name of self-determination. An iconic photograph from September 1920 of the French colonial general Henri Gouraud dressed in a splendid white uniform and flanked by two ‘native’ religious figures captures this moment. Seated to one side is the Patriarch of the Maronite Church, an Eastern Christian Catholic sect. On the other side is the Sunni Muslim Mufti of Beirut. Gouraud’s proclamation of the state of Greater Lebanon, or Grand Liban, which was carved out of the lands of the defeated Ottoman empire, served as the occasion. With Britain’s blessing, France had occupied Syria two months earlier and overthrown the short-lived, constitutional Arab Kingdom of Syria. The pretext offered for this late colonialism was one that continues to be used today. The alleged object of France in the Orient was not to aggrandise itself, but to lead its inhabitants, particularly its diverse and significant minority populations of Lebanon, towards freedom and independence.

Proclamation of Greater Lebanon in 1920. Photo by Photo12/Getty

France separated the Christian-dominated state of Lebanon from the rest of geographic Syria, which itself was parcelled out along sectarian Alawi, Druze and Sunni polities under overarching French dominion. This late colonialism was allegedly meant to liberate the peoples of the Arab world from the tyranny of the Ottoman Muslim ‘Turk’ and from the depredations of notionally age-old sectarian hatreds. Thus General Gouraud appeared in the photograph not as a vanquisher of supposedly barbarous native tribes; he was neither a modern Hernán Cortés toppling the Aztec Montezuma nor a French reincarnation of Andrew Jackson destroying the Seminoles of Florida. The French colonial general who had served in Niger, Chad and Morocco was portrayed as an indispensable peacemaker and benevolent arbiter between what the Europeans claimed to be the antagonistic communities of the Orient.

The colonisation of the Arab East had come after that of the Americas, South and Southeastern Asia, and Africa. This last great spurt of colonial conquest ostensibly repudiated the brutal and rapacious rule of the kind that King Leopold of Belgium had visited upon the Congo in the late-19th century. Instead, after the First World War, Europeans ruled through euphemism: a so-called ‘mandate’ system dominated by ‘advanced’ powers was established by the new British-and-French-dominated League of Nations to aid less-able nations. The new Lebanese and Syrian states blessed by the League were ‘provisionally’ independent, yet subject to mandatory European tutelage. Drawing on the British experience of ‘indirect’ rule in Africa, the victorious powers cultivated a native facade to obscure the coloniser’s hand. Perhaps most importantly, this late colonialism claimed to respect the new ideals of the US president Woodrow Wilson, the presumptive father of so-called ‘self-determination’ of peoples around the world.

Throughout modern history, the weight of Western colonialism in the name of freedom and religious liberty has distorted the nature of the Middle East. It has transformed the political geography of the region by creating a series of small and dependent Middle Eastern states and emirates where once stood a large interconnected Ottoman sultanate. It introduced a new – and still unresolved – conflict between ‘Arab’ and ‘Jew’ in Palestine just when a new Arab identity that included Muslim, Christian and Jewish Arabs appeared most promising. This late – last – Western colonialism has obscured the fact that the shift from Ottoman imperial rule to post-Ottoman Arab national rule was neither natural nor inevitable. European colonialism abruptly interrupted and reshaped a vital anti-sectarian Arab cultural and political path that had begun to take shape during the last century of Ottoman rule. Despite European colonialism, the ecumenical ideal, and the dream of creating sovereign societies greater than the sum of their communal or sectarian parts, survived well into the 20th-century Arab world.

The ‘sick man of Europe’ – the condescending European sobriquet for the sultanate – was not, in fact, in terminal decline at all in the early 20th century. Contrary to hoary stories of Turkish rapacity and decline, or romanticised glorifications of Ottoman rule, the truth is that the final Ottoman century saw a new age of coexistence at the same time as it also ushered in competing ethnoreligious nationalisms, war and oppression in the shadow of Western domination. The violent part of the story is well-known; the far richer ecumenical one, barely at all.

Along with almost every other non-Western polity in the 19th century, the Ottoman empire retreated in the face of relentless European aggression. The empire grappled with how to maintain sovereignty and accommodate itself to 19th-century ideas of equal citizenship. It was hobbled by the rise of separatist Balkan nationalist movements that enjoyed support from different European powers. The Ottomans were at war in virtually every decade of the 19th century.

If the Ottomans fretted about how to preserve the territorial integrity of their once-great empire, they also invested in reforming and refashioning it in almost every way, from its military and politics to its architecture and society. The empire had long discriminated between Muslim and non-Muslim in the name of defending the faith and honour of Islam. It also discriminated against heterodox Muslims. Over centuries, it had built an imperial system that enshrined Ottoman Muslim primacy over all other groups. In the 19th century, Ottoman sultans fitfully refashioned their empire as a ‘civilised’ and ecumenical Muslim sultanate that professed equality of all subjects irrespective of their religious affiliation. Muslim, Christian and Jewish subjects adopted the red fez as a sign of their shared modern Ottomanism. During the Tanzimat era (1839-1876), the Ottoman empire officially espoused a policy of nondiscrimination between Muslim and non-Muslim. The idea of equality between Muslim and non-Muslim in the empire acquired the force of social sanction and law with the promulgation of the Ottoman constitution of 1876, which declared the equality of all Ottoman citizens.

The massacres of 1860 reflected a global struggle to reconcile equality, diversity and sovereignty

No matter how much the Ottomans secularised their empire, Britain, France, Austria and Russia demanded more concessions. Each European power claimed to protect one or another native Christian or other minority community, each coveted a part of the Ottoman domains, and each jealously sought to negate their rivals’ influence in the Orient. This diplomatic wrangle was referred to at the time as the ‘Eastern Question’. The breaking up of the ideological and legal privileging of Muslims over non-Muslims in the empire was not without controversy, especially because European powers consistently intervened in the empire along sectarian lines. The Ottomans, for example, abolished the medieval jizya tax on non-Muslims but pledged to Europe in 1856 to respect the ‘privileges and spiritual immunities’ of the Christian churches; while they exempted non-Muslims from military service in return for a tax, they conscripted Muslim subjects to fight in seemingly endless wars; they opened Ottoman markets to an influx of European goods and tolerated Western missionary proselytisation of the empire’s non-Muslims.

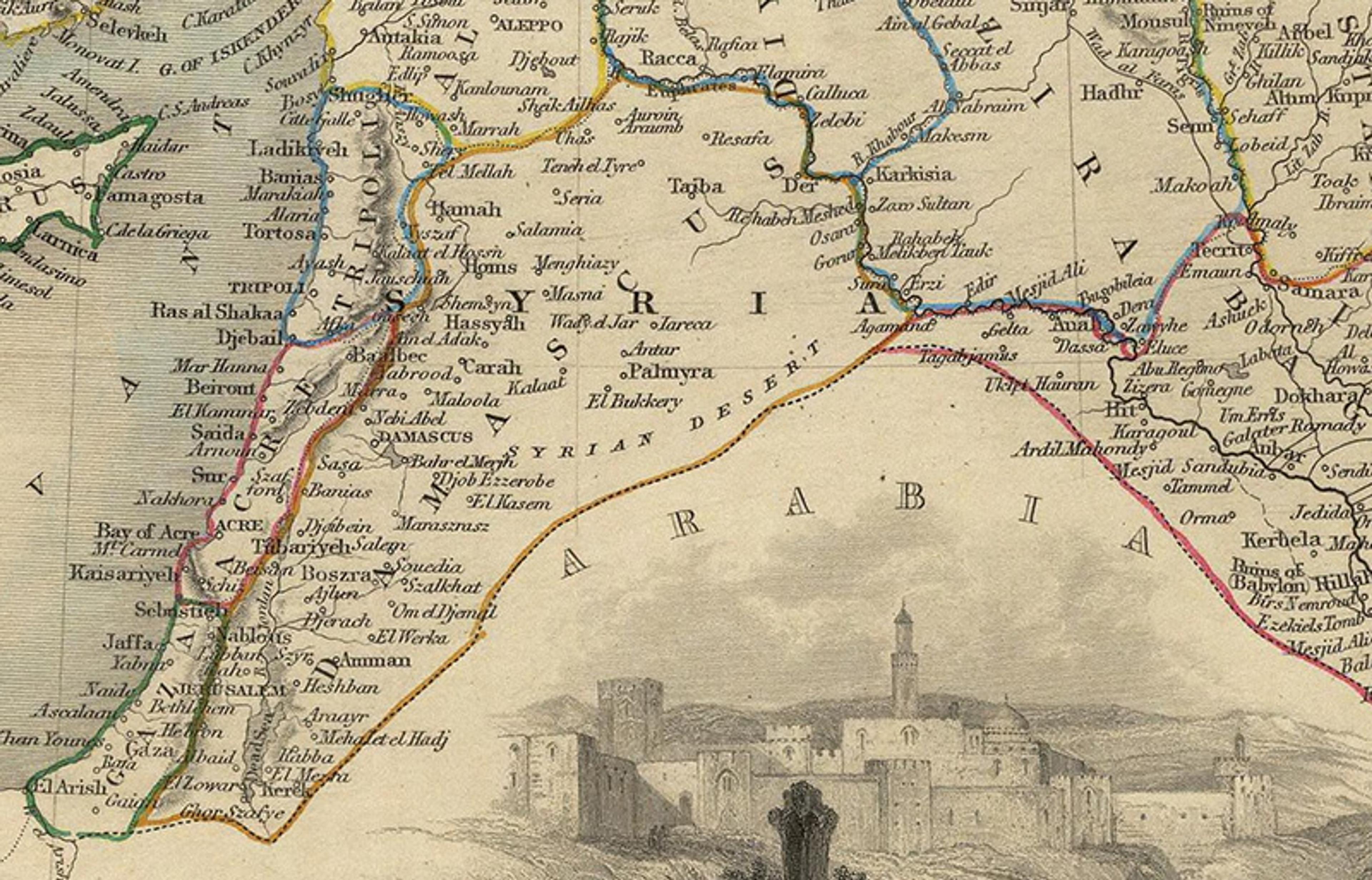

A section of the 1851 Martin and Tallis map ‘Turkey in Asia’ showing the southern eyalets (administrative divisions) of Ottoman Syria: Damascus, Tripoli, Acre and Gaza. Photo courtesy Wikipedia

In July 1860, an anti-Christian riot erupted in Damascus. Despite the edicts promulgating nondiscrimination, a Muslim mob rampaged through the city, pillaging churches and terrorising the city’s Christian inhabitants. Newspapers in London and Paris and missionary societies condemned what they saw as ‘Mohammedan’ fanaticism. The French emperor Napoleon III sent a French army to the Orient, allegedly to aid the sultan to restore order in his Arab provinces. European powers set up a commission of inquiry to investigate the massacres of 1860. Their humanitarian motives, however, were conditional and political. No corresponding commission, after all, was formed to investigate the US oppression and persecution of people of African descent or its extermination of Native Americans, the decades of French colonial terror in Algeria, or the British suppression of the anticolonial uprising in India in 1857.

Despite being singled out by Western observers as a peculiarly non-Western and even Muslim problem, the massacres of 1860 reflected a global struggle to reconcile equality, diversity and sovereignty that manifested across the world in very different contexts. So while the Ottomans were facing a genuine crisis about how to reform and maintain their grip over a heterogeneous multiethnic, multilinguistic and multireligious population, halfway across the world, the US was simultaneously fighting the deadliest war in the 19th-century Western world over slavery, racism and citizenship. The Damascus riot occurred just after the last illegal cargo of enslaved and brutalised Africans was unloaded from the schooner Clotilda on the Alabama coast.

The anti-Christian riots of 1860 in Damascus were terrible, but they reflected only one aspect of the contemporary Ottoman empire. Far less noted than the episodes of violence sensationalised in Europe was a noticeable and widespread accommodation, if not an active embrace, by many Ottoman subjects of secularisation and modernisation. The empire constituted a vital laboratory for modern coexistence between Muslim and non-Muslim that had no parallel anywhere else in the world. Nowhere was this coexistence more evident than in the cities of the Arab Mashriq. From Cairo to Beirut to Baghdad, Arabs of all faiths shared a common language and showed little inclination to separate politically from the Ottoman empire.

A general view of Beirut c1890-1900. Photo courtesy the Library of Congress

After the events of 1860, the Protestant Christian convert Butrus al-Bustani opened a ‘national’ school in Beirut. At a time when American missionaries in the Levant still rejected the idea of genuinely secular education, al-Bustani’s school was both antisectarian and respectful of religious difference. During an era when Africans and Asians were enduring gross racial subordination in European empires, when Jews were being subjected to pogroms in Russia, and when white Americans were embracing racial segregation across the US South, excluding Asians from US citizenship, and herding the surviving Native Americans into pitiable reservations, the Ottoman empire encouraged – or did not stand in the way of – the opening of new inclusive ‘national’ schools, municipalities, journals, newspapers and theatres. A new army was built in the name of national unity and sovereignty. All these reforms were made more urgent by successive Ottoman military defeats against Russia and in the Balkans, and Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid II’s resistance to constitutional change. In 1908, the Young Turk Revolution deposed the sultan and promised a new constitutional period of Ottoman liberty and fraternity among the various Turkish, Armenian, Albanian, Jewish and Arab elements of the Ottoman empire – not simply the absence of discrimination.

_Colle%CC%80ge_d'Antoura_la_%5B...%5DSalles_Andre%CC%81_btv1b531992612_1.jpg?width=3840&quality=75&format=auto)

Musical students at the Collège Saint Joseph in Antoura photographed by André Salles in 1893. Photo courtesy Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

Most of the secularising national reforms were far more enthusiastically pronounced than practised. They were implemented unevenly and piecemeal across the empire. Nevertheless, in the aftermath of the events of 1860, many Arab Muslims, Christians and Jews in the Mashriq believed they were participating in an ecumenical ‘renaissance’ or nahda that could be expressed in different Ottoman, Arab, religious, secular, political and cultural terms. They understood collectively that they were heading into a potentially brighter, and certainly more scientific, and more ‘civilised’ future. To be sure, from Egypt to Iraq, this nahda was dominated by urban and educated men who believed that they spoke for their respective ‘nations’. It was a renaissance in the making, not an accomplished goal or even a unitary social or political project. The nahda luminaries did not necessarily agree on the precise contours of their shared Ottoman nation any more than Americans then – or now – agree on what constitutes ideal or representative Americans.

Ottoman modernity promised a multiethnic, multireligious sovereign future – and a xenophobic world

The balance between the ecumenism of Ottoman reforms and the harsh imperative to maintain effective sovereignty was delicate. The ‘Eastern Question’ politicised the future of non-Muslim communities – eventually called ‘minorities’ – because they became simultaneously objects of European solicitude and pretexts for political and military aggression against the Ottomans. The emergence of ethnoreligious nationalisms in the Balkans exacerbated the problem when Christian Greek, Serbian, Macedonian and Bulgarian nationalists appealed to Russian, Austrian or British support seeking to break away from Ottoman control. Ottoman leaders, in turn, regarded the Turkish-speaking Muslim population as the essential core of their empire. In the last quarter of the 19th century, Armenian revolutionaries sought to emulate Balkan Christian nationalists. They appealed for European support to achieve autonomy; the Ottoman state responded with persecution.

Ottoman modernity in the shadow of Western colonialism could be both powerfully ecumenical and uncompromisingly violent. It promised both a multiethnic and multireligious sovereign future and a xenophobic world without minorities. In the Balkans and Anatolia, the imperative of sovereignty clearly trumped the commitment to ecumenism, while in the Arab Mashriq ecumenical Ottomanism flourished more easily. In the Balkans, Christians often became implacably opposed to Muslims (and other Christians) amid clashing ethnoreligious nationalisms, while in the Mashriq the Arab Christians and Muslims and Jews more easily made common cause.

One key difference was the absence of separatist nationalisms in the Mashriq. Although Britain occupied Egypt in 1882, in the rest of the Mashriq Ottoman rule remained viable. The shared Arabic language helped Arab Christians and Jews play important roles in the Arabic press, theatre, professional and women’s associations and municipalities. The leading Egyptian daily Al-Ahram, for example, was founded by a Syrian Christian émigré. Nor was it out of place that the Jewish journalist Esther Moyal would advocate for an ecumenical ‘Eastern Arab’ identity. The gradual alienation and decimation of the Armenian Christian community of Anatolia unfolded at the same time when Arab Christians and Jews coexisted with their Muslim brethren in cities such as Beirut, Haifa, Aleppo, Baghdad, as well as in British-occupied Cairo and Alexandria.

The Ottoman era ended with the calamity of the First World War. Wartime Ottoman Turkish rulers callously turned their back on the ecumenical spirit of Ottomanism at the same time as they embraced its darker statist side. In the name of national survival, these Ottomans commenced genocidal policies against Armenians. They also hanged those they considered Arab traitors in Beirut and Damascus. While a famine ravaged Mount Lebanon, Ottoman forces retreated before a British military invasion of Palestine. Jerusalem fell in December 1917. Almost a year later, the empire surrendered ignominiously.

When the victorious Allied statesmen of Britain, France and the US assembled in Paris in 1919 to decide the future of the defeated Ottoman empire, they intervened in an empire that had been substantially transformed over the preceding century. The victors of the First World War ignored the ecumenical heritage of the late Ottoman empire. Instead, they sensationalised the empire’s obvious defects and were determined to divide it up. In 1919, President Wilson blessed the partition of the Ottoman empire. The Greek invasion of Izmir set off a bloody war that led eventually to the victory of a new Turkey under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal, later known as Atatürk. This new Turkey secularised itself dramatically but was also draconian in its rejection of its own ecumenical Ottoman heritage. In 1923, Turkey concluded an agreement with Greece to forcibly evict – ‘exchange’ was the euphemism used – more than a million Greeks from the new Turkey. In turn, Greece evicted hundreds of thousands of Greek-speaking Muslims. The new Turkish republic then suppressed dissenting Kurds.

The Allies, in the meantime, decided the future of the Arab Mashriq. As early as 1915, Britain had pledged to support expansive Arab Hashemite ambitions to rule an independent Arab kingdom across much of the Arab East in return for their revolt against Ottoman rule. A year later in 1916, Britain and France then secretly agreed to divide the Arab provinces of the Ottoman empire between them in the Sykes-Picot Agreement. And in 1917, prompted by Zionist lobbying, the British government pledged to support the creation of a Jewish ‘national home’ in Palestine that was overwhelmingly Arab in its demographic, social and linguistic composition.

To add insult to injury, at the Paris peace conference in 1919, Britain and France blocked native Arab and Egyptian nationalists from presenting their cases for independence directly. They permitted, however, the Hashemite Emir Faisal, son of Sharif Hussein, to plead with the Allies to fulfil their wartime pledges to his father. They also allowed European Zionists to present their vision for colonising Palestine and transforming it into a Jewish state led by settlers from eastern and central Europe. And they heard from Howard Bliss, the son of an American missionary and the president of the Syrian Protestant College (today, the American University of Beirut). Bliss was allowed to speak on behalf of the inhabitants of Syria. While paternalistic to the Syrians, he was sensitive to the political mood in the former provinces of the Ottoman empire and recommended an impartial fact-finding inquiry be dispatched to the Middle East to document the political aspirations of its inhabitants by self-determination. The French were horrified by the idea of an impartial commission, and the British embarrassed, because neither had any intention of granting independence to the Arabs. Wilson himself, however, was the key interlocutor between the old and new forms of colonialism. He was deeply sympathetic to the American missionary enterprise. He also endorsed the idea of a commission.

‘In Palestine we do not propose even to go through the form of consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants’

The resulting American Section of the 1919 Inter-Allied Commission on Mandates in Turkey was known simply as the King-Crane Commission after the two Americans who led it: Henry King, the president of Oberlin College in Ohio, and the philanthropist Charles Crane. Unlike the 1860 international commission that was established in the Ottoman empire, this one actually polled people in the region – and the commission collected numerous telegrams, petitions and letters from the inhabitants of the erstwhile Ottoman provinces and held hundreds of meetings with them. Neither King nor Crane were anticolonial in any revolutionary sense, but they also both genuinely believed that it was important to record accurately the wishes of the indigenous peoples of the region. They appeared to take Wilson’s commitment to self-determination as self-evident.

After a gruelling tour through Palestine, Lebanon and Syria in July 1919, King and Crane reached several bold conclusions regarding the Arab East. They recognised that most of the inhabitants of the region spoke a common language and shared a rich ecumenical culture. They admitted that the political desire of most of the native population was overwhelmingly for independence. They recommended strongly that a single Syrian state that included Palestine and Lebanon be created under an American mandate (and failing that, a British one), with robust protection for minorities. Most importantly, they said that if the Wilsonian principle of self-determination was to be taken seriously, and the voice of the native Arab majority was to be heard, the project of colonial Zionism in Palestine had to be curtailed. ‘Decisions, requiring armies to carry out, are sometimes necessary,’ they wrote, ‘but they are surely not gratuitously to be taken in the interests of a serious injustice. For the initial claim, often submitted by Zionist representatives, that they have a “right” to Palestine, based on an occupation of 2,000 years ago, can hardly be seriously considered.’

The commissioners submitted their final report to President Wilson in August 1919, but their recommendations were ignored. Their predictions about Palestine, however, proved prophetic. The US repudiated any emancipatory anticolonial interpretation of self-determination, for Wilson himself never believed in the idea that all peoples were equal or immediately deserving sovereignty. Britain and France proceeded to partition the region as if the King-Crane commission had never been sent. The British foreign minister Arthur Balfour was, at least, candid on this point. The inhabitants of Syria, he said, ‘may freely choose, but it is Hobson’s choice after all’. France was going to rule Syria and Lebanon. And Britain was going to open Palestine to colonial Zionism. ‘For in Palestine,’ Balfour wrote in August 1919, ‘we do not propose even to go through the form of consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants of the country, though the American [King-Crane] Commission has been going through the form of asking what they are.’

No matter how intently the last colonialism of the world sold itself as a purveyor of self-determination, its Western proponents knew better. The real tragedy, however, lay not in deceit but in the divisions that this deceit exacerbated and engendered. Colonial Europe claimed to arbitrate age-old religious difference in the Middle East. In reality, it encouraged sectarian politics. The consequences of this last colonialism reverberate until today.