In April 1649, the earth of St George’s Hill in Surrey, England, was disturbed. A group of men and women calling themselves the ‘True Levellers’, known to history as the ‘Diggers’, had taken to the ‘wast[e] ground’ in the parish of Walton to protest enclosure, the process by which common land was parcelled into units of private property, stripping commoners of their traditional rights of access and usage. The land was bad – ‘nothing but a bare heath & sandy ground’, surveyors reported in 1650 – but the Diggers believed it could be made fruitful.

Over the coming weeks and months, they husbanded the earth, composting burnt turf, digging parsnips, planting carrots and beans. They even built cottages. Many knew the land well: the historian John Gurney estimated that about a third of the Diggers were local inhabitants. Their choice to join the Digger project was likely informed by years of local struggle: conflict with landlords, heavy Civil War taxation, the burdensome passage of troops through villages. But the object of their protest – enclosure – was hardly an issue confined to Walton: over several centuries, landowners across England had become ever more hungry to expropriate the commons from the commoners.

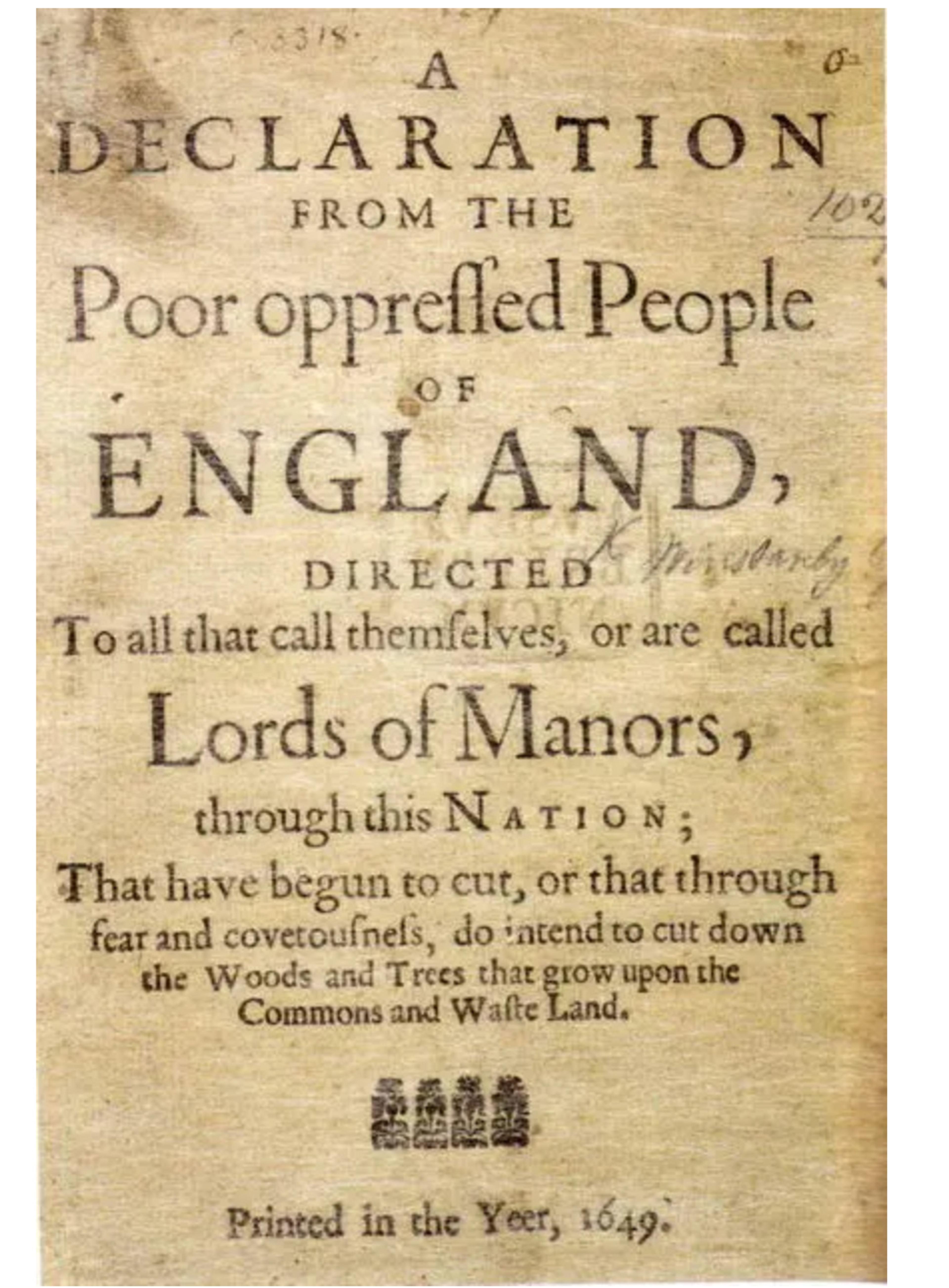

The True Levellers Standard Advanced (1649). Public domain

At first glance, this might seem like a local, intimate endeavour: Surrey men and women living and digging together, facing down attacks from manorial tenants and landowners animated, at least in part, by parochial resentments and rivalries. But the Digger imagination was vaster than St George’s Hill, than Surrey, than England even. The first Digger pamphlet, The True Levellers Standard Advanced (1649), was addressed to ‘the powers of England and to all the powers of the world’. In it, Gerrard Winstanley, the Diggers’ chief theorist, framed their digging as a means of claiming the whole ‘earth’ as a ‘common treasury of relief for all, both beasts and men’ (all quotes from the Christopher Hill edition, 1973). The scrubby, sandy Surrey ground would be the seed of an international revolution: ‘not only this common or heath should be taken in and manured by the people, but all the commons and waste ground in England and in the whole world …’ During four fervid years of textual and agricultural production between 1648 and 1652, Winstanley’s pamphlets laid out – and the Diggers enacted – a global vision of the commons, one that claimed to heed neither borders nor distinctions between ‘persons’.

‘The World Turned Upside Down’ (1985), Billy Bragg’s cover of ‘Diggers’ Song’ (1975) by Leon Rosselson, celebrating Gerrard Winstanley

Winstanley’s pronouncements are disorientatingly modern. The mid-17th-century writings of this smallish group of English brewers, artisans and farmers resonate with the words of later internationalists. Their vision of a border-crossing class of ‘common people’, on the brink of transforming the earth, chimes with the later address by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels to the ‘workers of the world’; Che Guevara’s calls for global, anti-imperialist struggle against the ‘oppressor classes’; the invocations of common cause among 21st-century resistance movements from Standing Rock to Palestine. How did the Diggers, sowing seeds in Surrey, come to understand themselves as part of a world-historical moment? How did they think about the threads tying their England to an increasingly tangled globe? What possibilities, what solidarities, did the Diggers’ global imagination encompass – and where was that imagination enclosed, fettered by borders and the world-shaping force of capital accumulation?

The Diggers are hardly the only English radicals of this period to have sought to turn the world upside down. In January 1649, following several tumultuous years of the Civil War, Charles I was executed by the authority of Parliament – the first and only time in English history that those claiming to represent the democratic will of the nation’s people had condemned a monarch to death. Like weeds on an untended common, countless radical groups – Muggletonians, Seekers, Ranters, Levellers and, yes, Diggers – sprung up to pose versions of the same fundamental question: if the divine power of a king could be overthrown, what other norms and forms of authority might be on the precipice of transformation?

More than any of their contemporaries, however, the Diggers have enjoyed a legacy extending, like their vision of the commons, all around the globe. After the German Marxist Eduard Bernstein plucked Winstanley’s writings out of relative obscurity in the 1890s, the Diggers were inscribed into the histories of multiple 20th- and 21st-century efforts to reimagine the world. In 1918 in Moscow, under Lenin’s auspices, an obelisk was carved with the names of ‘revolutionary heroes’ to commemorate the October Revolution: along with Marx, Engels, Mikhail Bakunin, Charles Fourier and others appears the name ‘Uinstlei’, for Winstanley. In 1960s San Francisco, an anarchist community action group took to the streets to distribute medical care, agitprop and coffee-can bread – they, too, called themselves the ‘Diggers’ in honour of the Surrey band. In 1999, on the 350th anniversary of the Diggers breaking ground, St George’s Hill was once again occupied by protesters: this time, from The Land Is Ours, a land justice campaign seeking to draw new environmentalist connections between this single patch of English soil and the wider world. The Digger story emerges and re-emerges as a site of imaginative possibility for people the world over, all working and thinking their way towards collectivist, ‘commoning’ relationships to land, resources and community.

Englishmen and women were bound up in the same webs of border-crossing exchange that shaped empires

But these global enmeshments were not just something that happened to the Diggers after they packed up their camps – after Winstanley wrote in 1650, as if to close the historical chapter: ‘I have writ, I have acted, I have peace …’ Far from it: the Diggers were always global. Their cottages and vegetable plots were embedded in a world already strung together by international flows of money and power. Their century saw the founding of the East India Company, the Virginia Company, and the Guinea Company, all working to enrich England through the intercontinental circulation of goods, people, and people traded as goods. The Digger ‘colonies’ in Walton and nearby Cobham were established on home soil amid the intensifying English colonisation of America, the Caribbean and Ireland. In 1649, the year the Diggers broke ground, England was shuddering from the shockwaves of a king’s execution and the establishment of a republican Commonwealth. But those shockwaves rippled across oceans, too: the same year saw a thwarted ‘conspiracy’ of the mostly white servant class of Barbados, terrifying planters and leading to 18 executions; Cromwell’s conquest of Ireland, meanwhile, was repeatedly threatened by domestic mutinies of the New Model Army. Mutinying soldiers exhausted by the recent Civil War openly interrogated the cost of foreign land: ‘what have we to doe with Ireland,’ they asked, ‘to fight, and murther a People and Nation … which have done us no harme, only deeper to put our hands in bloud?’ As the Diggers were beginning their commoning project, England’s imperial project was taking shape, flexing its muscles, stretching over oceans – and periodically finding itself pricked by sharp darts of resistance, both at home and abroad.

To what degree were these two projects in tension? How did the Diggers reconcile their millenarian visions of tyranny overthrown, prisons emptied and labour unchained from systems of ‘hire’ and ‘rent’, with efforts by England’s new republican government to extend its economic and political dominion overseas? To answer these questions, we need to examine Winstanley’s life, and the evolution of his thought through the Digger pamphlets. His history not only lets us glimpse how the revolutionary ferment of the English Civil War informed one man’s consciousness. It also reveals how individual Englishmen and women were bound up in the same webs of border-crossing exchange that shaped nations and empires – how, in the 17th century, Winstanley’s pious vision of mankind as ‘one family’ sharing an interwoven fate was also becoming an increasingly concrete historical reality.

Before Winstanley got his hands dirty churning up the earth on St George’s Hill, his life was shaped by another material: cloth. Cloth was the family trade, and Wigan, his birthplace, in northwest England, was a centre of textile manufacture, embedded within transregional and transnational trade networks. Linen was woven from local supplies and, increasingly, from imported Irish flax. Much of the finished cloth then travelled to London, as did many Wigan inhabitants – including Winstanley, who moved to the city as an apprentice in 1630, before setting up his own business in 1638.

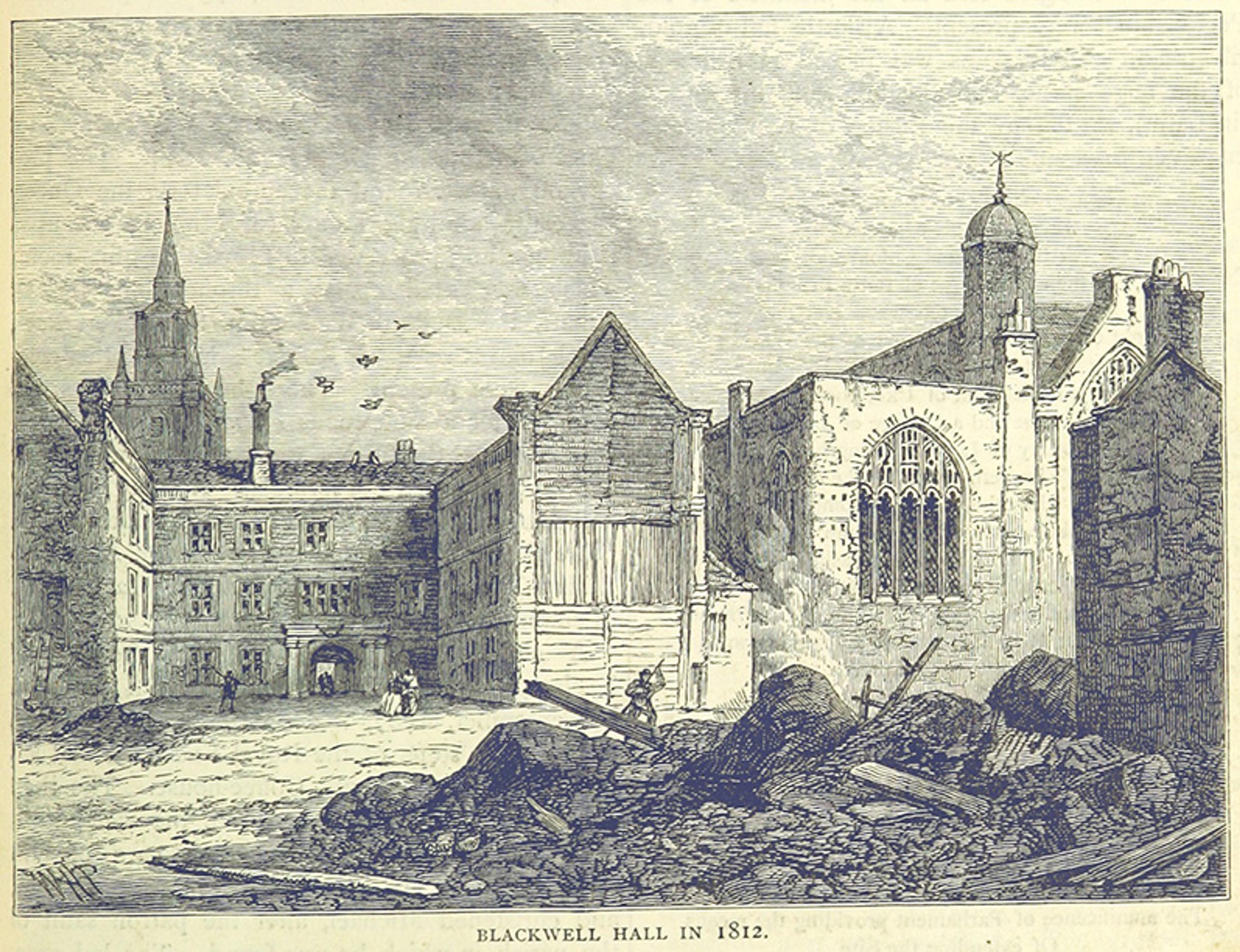

Blackwell Hall in the City of London in 1812, prior to demolition. Courtesy Wikipedia

To be a London cloth trader in this moment meant shepherding textiles over sometimes vast distances, scrambling in fashion’s quick-flowing currents for must-have stuffs, serges, flannels and fustians. It meant the clamour of Blackwell Hall, then one of the world’s largest commodity markets, and, as of 1604, the ‘appointed Market place’ for ‘all foreigners’ in the city to sell their ‘severall cloth [and] clothes’. It meant handling textiles from all corners of England, often bound for foreign markets: Germany, the Low Countries, Russia, the Levant, France, India, Portugal and the newly established American colonies. Occasionally, it meant contact with the fine Indian cottons imported by the East India Company, although it was only in the second half of the 17th century that Indian textiles truly came to dominate English markets. By the early 17th century, the complexity of the global textile trade coursing through Blackwell Hall was such that a dedicated class of middlemen, called ‘factors’, arose to navigate between clothiers’ supply and purchasers’ demand. If a 1656 detractor’s assessment of Winstanley as a ‘Blackwell-Hall-man-thief’ is anything to go by, he may have been one of these factors, connecting cloths to consumers across borders.

For Winstanley, life as a cloth merchant also meant vulnerability, both to human conniving and to the currents of history. The tumult of the English Civil War and related conflicts in Scotland and Ireland threatened his livelihood. He risked trading with Ireland, and suffered the consequences. In the wake of the 1641 Irish Rebellion, trade was disrupted, debts went unpaid, and in 1660 Winstanley reported that he was still owed £114 by a Dublin merchant named Philip Peake. Winstanley also appears to have been seduced by the glittering possibilities of trade farther afield. In 1642, he testified that a Mathew Backhouse had fraudulently acquired £274’s worth of textiles before absconding to Barbados. Backhouse, it seems, worked within the early triangular slave trade. He sailed with London goods to West Africa’s Guinea Coast, exchanged those goods for slaves, and then travelled to Barbados to supply slave labour for emerging sugar plantations. This was profitable trade – even more so if one managed to cheat one’s London suppliers out of their share. When Backhouse died on a Guinea Company ship sailing the Gambia River in 1651, he left his wife Elizabeth a legacy of English cloth, African cloth, ‘twenty five elephant teeth’, and an enslaved African ‘boy’. Perhaps some of Winstanley’s fabrics were caught up in that heap of ill-gotten goods; the record doesn’t specify.

Winstanley’s experience of being ground to near-ruin in the churn of the global cloth trade inflected his writings

All this left a bitter taste in Winstanley’s mouth – not Backhouse’s slaving, which he never mentions directly in his writings, but the fact of having been duped by the ‘cheating sons in the theeving art of buying and selling … out both of estate and trade, and forced … to live a Countrey-life’. The historical record bears out this narrative. Winstanley was bankrupted in 1643, left London, and is documented as a resident of Cobham by the end of that year. By 1649, he had established a life there as a householder, a writer of dizzying prophetic tracts, and a figure with enough station in his community to claim a central role in the Digger project.

We can’t pluck out any one biographical datum and hold it up as the source of Winstanley’s radicalism; we can’t locate the roots of the Diggers’ collective labour in the years-ago financial struggles of a single London trader. But I believe Winstanley’s experience of precarity, of being ground to near-ruin in the churn of the global cloth trade, inflected his subsequent writings – in particular, his acute understanding of the inextricability of the local from the global. A man who had lived among the chatter of Blackwell Hall’s international merchants, who had felt the financial twinges of Irish risings from across the sea, whose London stock had travelled to West Africa and been traded there for human lives, might well grasp that the movements of a clutch of Surrey Diggers could be relevant not just to the ‘powers of England’, but to the whole ‘world’.

Winstanley’s analysis often suggests a former trader’s sharp understanding of the profit motives underpinning global moves to power. ‘Wherefore is it,’ asks The True Levellers Standard, ‘that there is such wars and rumours of wars in the nations of the earth?’ The answer: ‘only to uphold civil propriety of honour, dominion and riches one over another, which is the curse the creation groans under …’ Winstanley’s professional experiences may help us account for the force of these proclamations. He would understand the forces driving the violent imposition of ‘dominion’ over, and the extraction of ‘riches’ from, subjugated peoples: he had made agreements with men like Backhouse who made their careers off such ‘trading in the world’. Presumably, Winstanley had once hoped to profit from this ‘trading’ himself.

More than simply grasping the implications of these violent, extractive appetites, however, Winstanley named them as violations of the divine image in which humanity was made. In An Appeal to the House of Commons (1649), he writes that: ‘The Nations of the world have rise up in variance one against another, … and stoln the land of their Nativity one from another’ only ‘since the fall’ – since the corruption by sin of the ‘Law of our Creation’. ‘Conquests’ do not stem from a God-given mandate: they are aberrations, and, in Winstanley’s millenarian understanding, ones that could not endure forever. Another world was possible, hovering just on the edge of the Diggers’ reality. When the ‘Day of God’ breaks, Winstanley wrote in 1648, ‘you shall see these great nationall divisions … swallowed up into brotherly one-ness’.

The Diggers’ work would usher in this global rupture of boundaries by refusing the imposition of boundaries on their common. It was in this spirit that Winstanley not only addressed the Diggers’ proclamations to the ‘powers of the World’, but made their demands, too, ‘in the name of the Commons’ of all the world’s ‘Nations’. The digging on St George’s Hill was a gesture towards the life of the world to come. First, Winstanley wrote, other English Digger colonies would emerge – and, indeed, by 1650, they did, in Northamptonshire, Buckinghamshire, Gloucestershire, Nottinghamshire and Kent – then, colonies beyond the sea would follow. If English cloth could be exported across borders, why couldn’t the spirit of English revolution?

That sequence – Surrey, England, the globe – is preserved across Winstanley’s writings. England is persistently accorded pride of place, even among nations of the promised new order. There are occasional exceptions. In a discussion of the ‘cheat[ing] and con[ing]’ endemic in English trade, one early pamphlet asks whether the ‘life of [English] Christians’ is truly ‘above the life of the heathens’, and warns English readers: ‘Surely the life of the heathens shall rise up in judgement against you …’ The pamphlet A New-year’s Gift for the Parliament and Army (1650) was written after persistent attacks on the second Digger colony, set up in Cobham after they were forced off St George’s Hill. It ends as if Winstanley is passing on the baton, laying open the possibility of any nation claiming the commoning revolution: ‘I must wait to see … whether England shall be the first land, or some other, wherein truth shall sit down in triumph.’ More often, though, Winstanley frames England’s status as the ‘first land’, the ‘most flourishing and strongest land in the world’, the ‘first of nations that is upon the point of reforming’, as a natural equation. England, after all, had just thrown off the ‘Norman Yoke’ of its own foreign conquerors – by which Winstanley meant the English kings, whose line of succession had been abruptly cut by a single axe stroke on 30 January 1649. Framing post-1066 monarchs as outside oppressors was a common rhetorical move for Civil War radicals, but Digger writings are particularly emphatic in characterising the English as both colonised and chosen, both radically free and perpetually subjugated: the ‘poor enslaved English Israelites’, even after Charles I’s execution, are still pursued by a ‘Norman power’ seeking to ‘imprison, oppresse, and kill’ them.

But there were also slier reasons to invoke England’s primacy. Winstanley’s patriotic rhetoric is most conspicuous in later pamphlets addressed to England’s new rulers, who were still negotiating the Commonwealth’s position on the international stage. Winstanley prodded at the new republic’s need to establish its standing among nations. Addressing Cromwell in The Law of Freedom in a Platform (1652), he reminds him: ‘You have the eyes of the people … all neighbouring nations over, waiting to see what you will do.’ Another pamphlet describes a conversation with an army officer who frets that, if ‘every one’ were granted common land, England would ‘do that which is not practised in any nation in the world.’ Winstanley’s consolation for the officer is, again, English exceptionalism: ‘what other lands do, England is not to take pattern’. England is to be the pattern, modelling for the world the correct commoning course. Should it ‘refuse’ to do so, Winstanley warns, ‘some other nation may be chosen before him, and England then shall lose his crown …’ When addressing England’s rulers and seeking their favour for his political project, the Digger who had once envisaged all nations swallowed up into ‘brotherly one-ness’ turned to stoking competitive anxiety about national status.

Claims for England’s primacy jar with calls for the abolition of all dominion

Winstanley also stoked more existential anxieties – about foreign invasion, and, with it, about the sovereignty and security of the English nation. Interestingly, the Diggers were portrayed by contemporary critics as threats to English defence, fanning the mutinous flames sweeping through the New Model Army. A 1649 pamphlet containing extracts of Winstanley’s Letter to the Lord Fairfax warned that the Diggers’ discursive ‘invasions’ were ‘obstruct[ing] and retard[ing]’ the ‘relief of poor Ireland’ (meaning Cromwell’s brutal conquest): this put England at risk of ‘subject[ion] to the furious cruelties of … strangers and foreigners’.

In reality, though, Winstanley often positioned the Diggers as supporters of the English army, and stressed the utility of the Digger political project in bolstering its military standing. Granting greater liberty to English subjects, one pamphlet claimed, would ‘make poor men willing to venter their lives’ for the Commonwealth, such that ‘if Scotch, French, Spaniards, Turkes, and all nations should come’, the army ‘would so unanimously stand together … that they should not invade’. Poor citizens’ displeasure with their conditions, Winstanley argued, was ‘the cause why many run away and fail our armies in the time of need’ – the pamphlet does not add that the most recent ‘times of need’ had often involved the conquest of another sovereign nation. Dissonant notes sound in the Diggers’ characterisations of war, sometimes within the same pamphlet. The Letter to the Lord Fairfax, and His Councell of War (1649), for instance, contains both a sharp assessment of ‘all wars, blood-shed, and misery’ as the product of ‘one man indeavour[ing] to be a lord over another’, and a jingoistic image of Fairfax’s ‘souldierie’ as a ‘wall of fire round about the nation to keep out a foreign enemy’.

There are stark tensions here. Claims for England’s primacy jar with calls for the abolition of all dominion; the promotion of militarised borders jars with visions of the earth as an unbounded, ‘common treasury’; plaudits for a conquering army jar with a grave awareness of war’s realities. We could understand these tensions as products of a desire to curry favour with England’s authorities and win protection for precarious Digger settlements from the very powers Winstanley elsewhere accused of extending the ‘Norman Yoke’. We could paint them as circumstantial lapses of the Digger vision, rather than perspectives embedded within it. We could do this – were it not for The Law of Freedom in a Platform (1652).

The Law of Freedom is the last known Digger pamphlet by Winstanley, and perhaps the most famous. By that year, the Digger colonies were no more. Local landlords had succeeded in driving them off the common and forcing them to disband: there was no longer any need, therefore, to sweet-talk army generals into offering protection for a clump of hillside cottages. Winstanley was now at liberty to articulate his unconstrained political vision. The Law of Freedom offers a detailed revolutionary programme. It imagines a society in which money, land ownership and wage labour have no place, governance derives from direct democracy, and individual needs are provided for by the collective. There are notable differences from Winstanley’s earlier works. Scholars have been fascinated and, occasionally, disturbed by his turn from prophetic, utopic, convention-shattering political revelation to listing 62 state-administered ‘laws … whereby a commonwealth may be governed’. Still, as an ‘experiment in imagining otherwise’, to borrow a phrase from the Black feminist writer Lola Olufemi, it’s a work of powerful vision, pivoting around the search for the Commonwealth’s ‘true foundation-freedom’.

But Winstanley’s vision of freedom no longer enfolded the wider globe. Money would be outlawed in his commonwealth – except for the sake of trade with other nations, which ‘as yet own monarchy, and will buy and sell’. As such, Winstanley says – with the old trader’s acumen – ‘it is convenient’ for the Commonwealth to engage in the international commodity trade. That trade would operate ‘according to the law of navigation’. This is the text’s only approving reference to recent, real-world English legislation. The 1651 Navigation Act stipulated that goods could be carried to England and its colonies only by English ships, and was designed to create a monopoly on colonial trade, bolstering England’s imperial power at the expense of the Netherlands. Winstanley’s imagined commonwealth does away with almost every structure of domestic financial coercion, but preserves an Act geared towards England’s mercantilist control over its colonies. It also preserves the Commonwealth’s army – ‘to withstand the invasion or coming in of a foreign enemy.’

How can we hold both in our readings of the Diggers, and in our own efforts to dig new worlds out of bad earth?

We can’t account for all the tensions between the Law of Freedom and Winstanley’s earlier works, or for the contradictions between the different seasons of his documented life. Why, for instance, would a man who passionately called for the liberation of the poor from ‘enslavement’ by financial coercion then propose enslavement as a punishment for crimes against the Commonwealth? For that matter, how could a man who crusaded against such ‘slavery’ later find himself entangled, for a second time, with a slaver – this time, Ferdinando Gorges, a wealthy merchant nicknamed ‘King of the Black Market’, who pretended friendship to trick Winstanley out of an inheritance in the later 1660s? It’s not as though opposition to slavery, militarism and extractive commerce were unthinkable in Winstanley’s England. The anonymous author of the pamphlet Tyranipocrit Discovered (1649), for example, decried both ‘our Indian merchants’ for ‘robbing of the poor Indians of that which God and nature hath given them, and … mak[ing] them slaves’, and the English for ‘hunt[ing]’ the ‘poor Irish’. Yet, for Winstanley, these ongoing historical processes remained peripheral – or, at least, they found little place in his Digger writings. How could what Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker call Winstanley’s ‘planetary consciousness of class’ embrace such vast horizons – and yet simultaneously glide over so many material realities of the Diggers’ interconnected world?

Of course, part of the answer lies in the fact that none of us live politically or ethically consistent lives. We often choose not to face up to the ways in which our present reality might be in tension with our past selves, or how our political commitments might conflict with our consumer habits. Sometimes, these tensions surface only in scholarly retrospect – if, indeed, they surface at all.

Still, though, it’s useful to look at a political imagination as capacious as Winstanley’s and ask – what was it capable of envisaging? What was it not? Which realities did it confront, and which did it flinch from? There is friction in Winstanley’s visions of a moneyless commonwealth that would somehow retain the 1651 Navigation Act, of a peaceful republic still clinging to its army. That friction emerges from contact between a genuine, if indistinct, impulse of solidarity towards the world’s poor and oppressed, and the specific, grinding ways in which emerging global systems were working upon particular nations, particular bodies. How can we hold both these things in our imaginations – both in our readings of the Diggers, and in our own efforts to dig new worlds out of bad earth? How can we assert that the earth is a ‘common treasury’, and mean it, mean all its implications, imagined to their furthest extent, all the way to the horizon?

I have asked myself and others versions of these questions many times – in particular, over this past year, while spending time in a Palestine solidarity encampment that, like the Diggers’ project, took the form of local action addressing itself to ‘the powers of England, and to all the powers of the world’. I like to imagine that Winstanley and his comrades had similar conversations sitting on the side of St George’s Hill – about what solidarity can encompass, about how the world might look next spring, about hope. I imagine they, too, did not have all the answers.