On 31 July 2024, an intriguing ceremony took place on Pheasant Island, a tiny sliver of land in the river Bidasoa, marking the border between France and Spain in the Basque Pyrenees. Under a lush canopy of trees, a handful of people disembarked from rubber dinghies and walked towards a monument, the only man-made structure on the island. Most of them were wearing the pristine white uniforms of the French and Spanish navies. The walk was a short one, as the island is only 200 metres long and 40 metres wide.

Near the monument, there were speeches. Floral wreaths were laid down, trumpets, cornets and bugles resounded, and a number of gun salutes were fired. On the flagpole, the Spanish bandera was lowered and the French tricolore hoisted. The island’s anthem – yes, it has one, despite being uninhabited – was played. The atmosphere was a unique blend of solemn military protocol and gleeful exuberance, just like it was the previous year and the years before. Every year on 31 July, France reassumes sovereignty over Pheasant Island, six months after it has been transferred to Spain.

Courtesy hendaye.fr

Courtesy hendaye.fr

The island, with an area smaller than a soccer field, changes nationality twice a year. Pheasant Island is the only example in the world of a temporal condominium, a political territory shared by multiple powers with alternating sovereignty. Governance is, in turns, entrusted to the French and the Spanish naval commanders stationed at Bayonne and San Sebastián, who carry the honorific title of ‘viceroy’ – a curious title, especially in France, where royalty has ended in exile or decapitation.

In 2022, for the first time, a vicereine was appointed, Pauline Potier, a naval commander and deputy director in the French civil administration. Upon assuming her functions, she said that the strange fate of the island was more than just amusing folklore: ‘It is a symbol of the success of diplomacy over war.’

Plan of Pheasant Island (Île des Faisans) c1660, at the time of the Treaty of the Pyrenees between France and Spain. Courtesy Gallica/Bnf

Pheasant Island (Île des Faisans in French, Isla de los Faisanes in Spanish, Konpantzia in Basque) has been undivided since November 1659. It was here that the Treaty of the Pyrenees was negotiated and signed, bringing an end to decades of war between France and Spain. Top diplomats like Cardinal Mazarin and Don Luis Méndez de Haro sat together for months in a temporary building to discuss the terms of peace, including a new border between the two kingdoms, the one that still runs through the Pyrenees today.

Portrait of Jules Mazarin (1658) by Pierre Mignard

The successful peace talks were sealed by a royal marriage six months later when 21-year-old Louis XIV of France, the future Sun King, set foot on the tiny island to receive the Infanta Maria Theresa, daughter of the Habsburg king Philip IV of Spain, as his bride. She came walking through the Spanish side of the sumptuous pavilion that was decorated by none other than Diego Velázquez, the most brilliant painter of his time.

The Treaty of the Pyrenees was a triumph of modern diplomacy. It served as the capstone to the Peace of Westphalia, the continent-wide settlement that put an end to a century of devastating wars in Europe. The preceding Thirty Years’ War (1618-48) had been the most brutal phase, killing approximately 8 million people. Europe had been ravaged from Sweden to Spain, a third of Germany’s population was gone, it was the bloodiest conflict on the continent before the First World War. But diplomacy had brought it to a close and the deal on Pheasant Island completed it.

What happened in Westphalia still shapes the way we conduct international relations today, now on a global scale. Planetary politics is still very much in its infancy, but the format it takes is invariably diplomatic: the 2015 Paris Agreement, for instance, was negotiated by national diplomatic delegations. And if the history of diplomacy teaches us one thing, it is that institutions, when faced with existential challenges, can change and reinvent themselves accordingly. By looking back, we may not only find a few insights but also some hope.

Modern diplomacy goes back to early 17th-century Europe from where it spread across the globe. Of course, there is nothing intrinsically ‘Western’ or ‘European’ about diplomacy. For millennia, countries and civilisations have been engaged in formal talks with other countries and civilisations. Mesopotamian city-states concluded peace treaties with each other around 2500 BCE. Egyptian pharaohs had envoys negotiating peace with the Hittites as early as 1259 BCE. The Greek city-states of the 1st millennium BCE had heralds and honorary consuls for short- and long-term representation abroad.

Around the same time, a sophisticated system of diplomacy developed in ancient China between the feuding kingdoms of the Warring States period (475-221 BCE). In India, Emperor Ashoka used diplomacy to spread Buddhism throughout the subcontinent in the 3rd century BCE. The Maya and Inca kingdoms, too, relied on envoys to represent their interests in the wider region, as did the Romans, the Vikings, the Arabs, and the Vatican.

Yet something peculiar happened in early 17th-century Europe. Diplomatic envoys no longer just represented their king, emperor, sultan or pharaoh, but something new and infinitely more abstract: the state. And it was this vision of diplomacy that would become dominant in modern times.

Diplomacy was distrust clad in good manners

When Geoffrey Chaucer was sent as an emissary to Italy between 1372 and 1378, he was basically on personal business trips for Edward III. The king sought to get a loan from the Florentines, a harbour from the Genoese, and a daughter-in-law from the Milanese.

However, when in the 1620s Cardinal Richelieu, France’s principal minister under Louis XIII, established the first modern foreign ministry, its foundational principle was not royal benefit, but raison d’état, the national interest. The concept had been championed by Niccolò Machiavelli a few decades earlier in Florence, and Richelieu applied it to the Thirty Years’ War. As a Catholic, he chose to support the Protestant Swedes against the Catholic Spaniards – a cynical move that made France dominant in Europe.

For Richelieu, the modern state was a political organisation with a strong centralised power holding exclusive sovereignty over a clearly defined territory. In order to scrupulously observe the balance of power with other states, highly skilled diplomats had to be organised in a permanent professional corps, with ambassadors settling abroad for years, not months. Only in this way could they gather all relevant intelligence, report back to the homeland, and engage in what Richelieu called la négociation continuelle.

His vision laid the foundation for the system of sovereign states that was formalised in 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia. During this first act of diplomatic history (1600-1800), negotiations took place mainly on a bilateral basis: France with Spain, Sweden with Russia, Poland with the Holy Roman Empire. Diplomacy was about defining borders, maintaining balances of power, and defending national interests. It was distrust clad in good manners.

The Ratification of the Treaty of Münster (1648) by Gerard ter Borch II. The treaty was part of the Peace of Westphalia. Courtesy Rijksmusuem

Of course, this new type of diplomacy would not stop all wars, but it became increasingly favoured as an alternative to armed conflict. A good ruler, wrote the influential French diplomat François de Callières in 1716, must not ‘employ arms to support or vindicate his rights until he has employed and exhausted the way of reason and of persuasion.’ Like many others in the Enlightenment, he hoped for a world order built on reason and dialogue rather than religion and war.

When France emerged as the dominant political power on the continent, Richelieu-style diplomacy spread across Europe, and French became the primary language of international affairs, giving us terms like corps diplomatique, chargé d’affaires, aide-mémoire, attaché, communiqué, entente, détente, accord, protocol and passport.

As a side-effect, French etiquette and gastronomy gained worldwide prominence. Whether Richelieu can be fully credited for having introduced the blunt table knife at formal dinners remains uncertain (he is reputed to have abhorred the custom of using knives for picking teeth – or fights), but la nouvelle cuisine française of the 18th century did put entirely new food items like oysters, lobsters, truffles, foie gras and champagne on the menu of the aristocracy from Russia to America. Life seemed good under the ancien régime, and nothing appeared poised to change it.

A new chapter started with a bang. In 1814, the Austrian foreign minister Prince Klemens von Metternich was convinced that diplomacy had to make a fresh start. After the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars, the old order was clearly over. Leisurely bilateral chats by wig-wearing, white-powdered aristocrats sipping coffee or tea in rococo salons while gently discussing some border issue would no longer do. Napoleon’s conquest of continental Europe had shattered the old balance of power, and a radically new brand of diplomacy was needed, one that was built on the consensus of the European governments.

Metternich became to diplomacy’s second act what Richelieu had been to the first: its main architect. As a political conservative deeply preoccupied by stability, he favoured monarchism over all sorts of revolutionary adventures. He certainly did not go as far as Immanuel Kant who had suggested that long-lasting peace could be realised by bringing different countries together in a federation of free states, but he did side with the idea that international diplomatic cooperation was now key to political stability in Europe.

The Congress of Vienna (1815) by Jean-Baptiste Isabey. Courtesy the Royal Collection

Act II saw the emergence of multilateralism as a foundation of modern diplomacy, and would remain dominant for the next two centuries. In 1814 and 1815, the Congress of Vienna brought together delegates from five major powers and 12 other nations to deal with the aftermath of Napoleon. Together, they drew a new map of Europe and crafted a delicate balance of power that was to be overseen by the so-called ‘Concert of Europe’, a general agreement on multilateral consultation that had never existed before and lasted until the outbreak of the First World War. If the world changed, diplomacy had to change too.

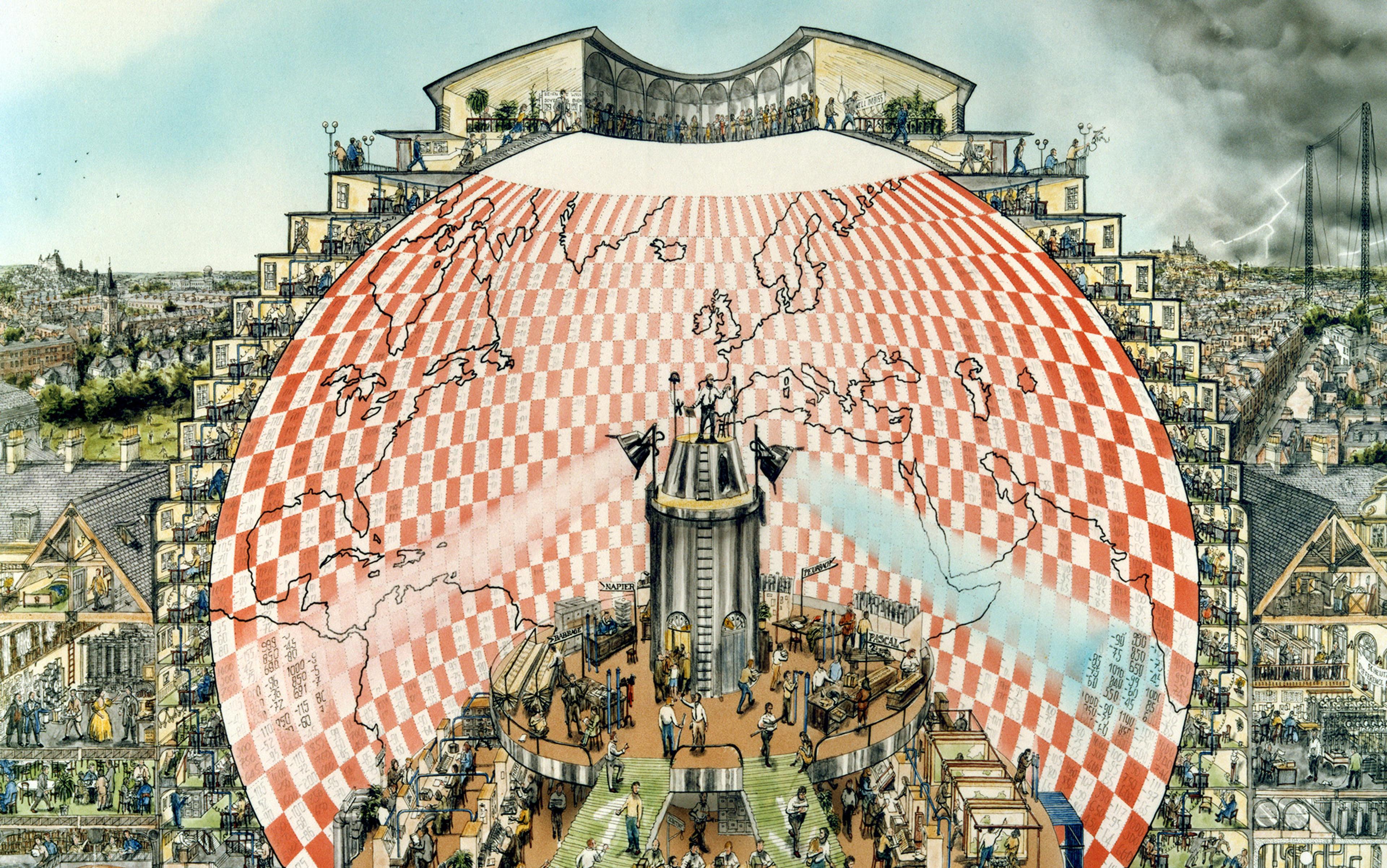

La balance politique (1815), formerly attributed to Eugène Delacroix. Courtesy BnF, Paris

The model set up by Metternich in Vienna was soon repeated elsewhere for more topical discussions. The Berlin Conference of 1884-85 brought together 14 European nations with imperial ambitions to discuss the rules for colonising Africa. The Hague conventions of 1899 and 1907 had dozens of countries negotiating the rules of warfare. Multilateralism did not necessarily equate to internationalism. At this stage, it could be best understood as a form of ‘international nationalism’. The concept of raison d’état remained paramount, but if that ideal could be achieved by multilateral dialogue, all the better.

The rise of multilateralism did not spell the end of bilateral diplomacy

This period of increased international exchange also gave rise to the World’s Fairs (first in London, 1851) and the modern Olympic Games (Athens, 1896). It was multilateralism for the millions: competitive entertainment where European countries came together to challenge each other.

The First World War ended the Concert of Europe, but not multilateral diplomacy. The Treaty of Versailles (1919) deepened Metternich’s model. Multilateralism became the norm and took on a permanent form with the League of Nations, a first attempt at institutionalising international dialogue, which proved rather toothless in practice. After the Second World War, multilateralism was approached even more thoroughly, with the United Nations as its most important outcome. The UN was meant to succeed where the League of Nations had failed: maintaining world peace. In the 1950s, just after completing his PhD, Henry Kissinger wrote that, in an age of nuclear threat, it was ‘only natural’ to look at the Congress of Vienna, ‘the last great successful effort to settle international disputes by means of a diplomatic conference’.

After the end of the Second World War, multilateral institutions flourished: the International Atomic Energy Agency, the World Health Organization, the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. On a regional level, the European Union came about, as did the African Union, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Mercosur (the Southern Common Market), the Pacific Alliance, the Non-Aligned Movement, and many others.

The rise of multilateralism did not spell the end of bilateral diplomacy, as countries continued to engage in mutual negotiations. In practice, there was considerable overlap between the two approaches. Major international conferences would focus on multilateral discussions during plenary sessions while leaving room for bilateral talks during coffee breaks, breakfast meetings and dinner parties.

Classical bilateral diplomacy also spread globally, as countries decolonised and the Cold War ended. What had been a Western style of diplomacy served as a template for many new African, Asian and east European regimes. The UN membership expanded from 51 members in 1945 to 193 in 2024, adding a new layer of diplomatic dialogue.

Somehow it worked.

For all its shortcomings – multilateral organisations are notoriously unwieldy and bureaucratic – Act II diplomacy has contributed to a safer world. There has been less warfare between countries in recent decades, and fewer people have died annually from armed conflict in the past 30 years than in the previous century, despite the recent wars in Ukraine, Ethiopia, South Sudan and the Near East. The result is far from being perfect but, as the former UN secretary-general Dag Hammarskjöld once said, multilateral bodies like the UN were ‘not created in order to bring us to heaven, but in order to save us from hell.’ That minimal programme has been achieved, somehow. That the postwar world has remained free from nuclear warfare is a success story for which multilateral diplomacy deserves more credit than it usually gets.

It was no coincidence that the classic model of multilateral negotiation was chosen when, starting in the 1970s and ’80s, an entirely new threat to world peace emerged: global warming. How was this hell to be averted? In 1988, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was established – the UN climate panel – followed by the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1992, which was signed by 166 countries and now counts 198 parties. Its highest decision-making body is the annual Conference of the Parties, or COP, which led, among other things, to the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 and the Paris Agreement in 2015.

International climate policy is thus the direct heir to four centuries of diplomatic history. From the 17th and 18th centuries (the first act), it inherited the notion of sovereign states; from the 19th and 20th centuries (the second act), the willingness to engage in multilateral dialogue. But raison d’état – the enlightened self-interest of anthropocentric world politics – was thereby anchored at the heart of the fledgling planetary geopolitics. That could not remain without consequences.

‘It is an enhanced, balanced, … historic package to accelerate climate action,’ said Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber during his closing remarks as president of COP28 in Dubai in December 2023. ‘We have language on fossil fuel in our final agreement … We have helped restore faith and trust in multilateralism. And we have shown that humanity can come together to help humanity.’

The unexpected climate accord was hailed as ‘a diplomatic victory’ by The New York Times, ‘a landmark deal’ by Le Monde, and ‘a historic consensus … of milestone significance’ by the Chinese press agency Xinhua. The main reason for this almost universal praise was a line in the agreement that called on countries to start ‘transitioning away from fossil fuels’. Such explicit language was a first in 28 years of COP.

There was something peculiar about the enthusiasm. Why did it take nearly 30 years – and almost 200 diplomatic delegations – for an annual international climate conference to formally acknowledge what scientists had long shown? Negotiators had known for decades that climate change is anthropogenic, that fossil fuels cause more than 75 per cent of emissions, and that even modest warming brings serious consequences. They also knew 2023 was the hottest year on record, at that point. So why did they merely ‘call on’ countries to ‘transition away’ from fossil fuels ‘by 2050’ in an ‘orderly’ fashion, without binding commitments?

The answer is straightforward: faced with diverging national interests and relentless industrial lobbying, traditional multilateralism has proven tragically inadequate for addressing long-term planetary crises. Despite the stability and cooperation it once delivered, modern diplomacy is falling short in the face of fundamentally new threats. We have outlived Act II, but not yet entered Act III. Since the millennium, we’ve been stuck in an extended intermission, with diplomacy paused while Earth’s drama intensifies.

We are unprepared for the storms ahead and unwilling to redesign the vessel

And climate change is only one of several critical challenges. Scientists have identified nine planetary boundaries; six have already been crossed. Besides climate, these include changes in land and freshwater use, biodiversity collapse, disruptions to nutrient cycles, and the spread of novel entities like PFAS (‘forever chemicals’), GMOs and microplastics. Ocean acidification is now reaching a tipping point. These threats are scientifically clear, yet none has been met with adequate international action.

In truth, the Earth system is entering uncharted waters, but diplomacy still behaves as if we’re in familiar territory. We are unprepared for the storms ahead and unwilling to redesign the vessel. It is 1814 again – but without Metternich’s imagination. Today’s diplomats remain bound to institutional tradition, while even the most conservative figures of the past showed greater adaptability.

If an attempt is made to rethink international relations, it usually boils down to another fruitless debate on the much-needed yet never-realised reform of the UN Security Council. When the gaze is institutional, the solution is institutional. Multilateralism today is hampered by its inability to renew itself. Meanwhile, the postwar world order is visibly falling apart.

Just as humanity should be uniting to confront its greatest challenge yet – safeguarding the planet’s life-support systems – we are more divided and less resourceful than ever. Regional wars destabilise old power structures, geopolitical shifts create new fault lines, and international agreements unravel.

With each passing year, the UN seems to resemble the world of 1945 more than the world as it might look in 2045 – soon, the organisation may follow the same path as the League of Nations. And each year, COP grows larger, but also more toothless – the power of the fossil fuel lobby is increasing steadily. At the 2023 climate summit in Dubai, no fewer than 2,456 fossil fuel lobbyists were granted official access passes, four times more than the year before. They outnumbered all official delegations from scientific institutions, Indigenous communities, and vulnerable countries combined. Even the presidency was held by one of the fossil sector’s top CEOs, the previously mentioned Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber. ‘We’ve just decided to not even disguise it anymore,’ Al Gore fumed. He called for reforming these international institutions ‘so that the people of this world, and including the young people of this world, can say: “We are now in charge of our own destiny. We’re going to stop using the sky as an open sewer. We’re going to save the future and give people hope.” We can do it!’

Yet, in the meantime, nothing happens. While Metternich swiftly reimagined diplomacy after Napoleon, we appear remarkably sluggish in responding to the urgent demands of life on a burning planet.

The UN was founded to manage conflicts between countries, not between humanity and the planet

The reason why tools from the past won’t suffice is that the task involved has become dramatically different. The planetary polycrisis we are facing is not a regular war, nor even a world war or a global nuclear threat. We are talking about an entirely new form of complexity here, well beyond classical intrahuman conflict. The polycrisis is anthropogenic in its origin, but it cannot be anthropocentric in its solution. It has become a physical reality of its own, with its own ever-accelerating dynamics, its own centrifugal forces catapulting the more-than-human consequences away from its human causes.

And here lies the heart of the problem: the Earth system is in deep crisis, but we confront it with the usual solutions of the human world. No wonder that the existing concepts – national sovereignty, raison d’état, multilateral diplomacy, and so-called stakeholder engagement (a polite term for consultations with lobbyists) – fall so painfully short. The UN was founded to manage conflicts between countries, not to resolve the conflict between humanity and the planet. A flat organisation cannot solve a vertical problem.

Where did we go wrong? Somewhere along the road of postwar politics, we have begun to assume that ‘international institutions’ were synonymous with ‘global governance’ and that that was enough. We forgot that the word international meant just that: inter-national, literally between different nations. That was the logic underlying the conferences in Vienna, Berlin or The Hague. But the planet is more than a sum of countries. Clinging to the multilateral paradigm is like trying to run a country with just a convention of mayors. No wonder parochial imperatives continue to prevail over planetary needs.

How can national sovereignty remain the bedrock of international relations when we are faced with colossal planetary challenges? What can be ‘foreign’ about ‘policy’ when on the most existential of issues the world is more deeply interconnected than ever? The whole notion of ‘foreign policy’ feels increasingly meaningless in the age of planetarity. The clearcut distinction between foreign and domestic affairs comes from a time when the geophysical fiction of borders largely shaped historical societies. But extreme weather patterns, biosphere integrity, ocean acidification, sea level rise, freshwater change, mass migration, global pandemics and runaway machine intelligence laugh at the political boundaries between nation-states. This does not mean that we have to do away with borders altogether – they still structure part of our lives – only that we have to start thinking about levels of diplomacy that are not sovereignty-driven. Beyond the logic of raison d’état, we urgently need to develop the principle of raison de Terre – an encompassing approach that prioritises the interests of the Earth system above all national considerations.

Pleading for the relativisation of national sovereignty undoubtedly sounds, at first glance, like heresy. It concerns nothing less than the granite foundation of four centuries of modern diplomacy, which still forms the basis of the UN today. Doesn’t the UN Charter itself state that relations between countries must be ‘based on the principle of the sovereign equality of all its Members’? A noble principle, certainly – but the result is that we are no longer capable of viewing the world in any other way than as a colourful puzzle of countries.

This, however, is a very recent reality. The idea that Earth was neatly divided into a patchwork of nation-states, all guarding their sovereignty and engaging in diplomacy with one another, had not been true for very long. In Children of a Modest Star (2024), the political scientists Jonathan Blake and Nils Gilman argue that, in 1945, half the world’s population did not live in a nation-state, but in a mandate territory, colony, protectorate or overseas possession. Only from around 1965 onwards have nearly all people on Earth lived in modern states. This, of course, is thanks to the wave of decolonisation. Colonies had to become countries, foreign domination had to give way to autonomy, and all these new nations had to be treated as equals. Wonderful ideals – but they also led to an absolutisation of the principle of sovereignty. What was in reality a relatively recent and arbitrary development – the world as a jigsaw puzzle of autonomous states – was etched in stone and presented as timeless.

Today, the EU proves that it is possible to add a layer of decision-making that transcends the individual nation-state without denying national dynamics. Why shouldn’t this be possible on a global scale? Europe is far from perfect, but it has given its member states a degree of clout they did not have on their own. Why should a global governance structure that is slightly less voluntary than the current UN be considered unthinkable by definition? Why do we stubbornly cling to an outdated horizontal model that, with each passing day, proves itself unfit for planetary problems?

The discrepancy between what people expect and what diplomacy delivers is quite staggering

Contrary to what social media and political rhetoric often suggest, humanity is much less divided in terms of planetary politics than we tend to think. A massive poll conducted in 2024 by the UN Development Programme and the University of Oxford reveals that 80 per cent of the world’s inhabitants want their country to do more about climate change. With more than 73,000 people surveyed in 77 countries, who together represent 87 per cent of the world’s population, it counts as the largest public opinion survey on climate. The results are eye-opening: a majority of people in 80 per cent of the countries surveyed were more concerned about climate change than they were the previous year, 79 per cent think that richer countries should support poorer ones in their fight against climate change, and 86 per cent believe that countries should transcend their differences and work together to address climate change.

If a very large majority of humanity desires these outcomes, why do a large majority of diplomats fail to enact them? The discrepancy between what people expect and what diplomacy delivers is quite staggering. The world already embraces the raison de Terre, but where is the public sphere where the inhabitants of the world can speak as inhabitants of the earth? Where can they express themselves, apart from in an occasional poll? The answer is sobering: nowhere. Old-school multilateral diplomacy has hijacked the global conversation on the climate. Partisan groups with vested interests such as financial and industrial lobbies and major civil society organisations have easier access to the COP negotiators than billions of everyday people whose future it is all about.

Citizen participants in the 2021 Global Assembly. Courtesy the Global Assembly on the Climate Crisis

It was precisely for this reason that, in October 2021, the very first Global Assembly was held, a bottom-up initiative without formal mandate that drew the attention of the UN secretary-general António Guterres and the COP26 president Alok Sharma. With the help of a NASA database on human population density, the team behind the project generated a random sample of 100 dots that were plotted on a map of the world. At each of these dots, they sought a local partner to select four to six everyday citizens through conversations in the street or door-to-door recruitment. In order to achieve a balance in terms of age, gender, geographical distribution, educational attainment and attitude toward climate change, a final group of 100 participants was drafted by lot from the pool of 675 candidates. The organisers readily acknowledged that the number of participants was too small to be representative of the global population, but this was just a pilot and, with a budget just under $1 million, they did what they could.

The eventual group looked like a pretty good snapshot of the world. It contained 18 members from India, 18 from China, five from the US, four from Indonesia, three from Brazil, Pakistan and Nigeria, two from Russia, Bangladesh, the Philippines and the Democratic Republic of Congo, and one from 38 other countries. During the Assembly, 42 different languages were being used, with English, Chinese and Hindi being the most common. Participants came from all corners of the world. In line with global statistics, more than half of them were younger than 35, two-thirds lived on less than $10 a day, more than a third had never used a computer in their life, a third had never attended school, and 10 per cent could neither read nor write. Sixteen members belonged to an Indigenous community, and six were refugees.

In 12 weeks, they had achieved more than COP had in 30 years

Over a period of 11 weeks, the participants spent 68 hours together online, both in plenary and breakout sessions. One of the members was Li Shimao, a student from Wuhan, studying international trade; climate change was never a major worry for him. During the sessions, he met Mohamed Salem, an elderly goat farmer from the Yemenite island of Socotra who had to travel 60 km to get online. Mohamed told Li and the other assembly members how his goats were suffering from repeated droughts, as the landscape was getting increasingly barren. There was also Madeleine Kiendrebeogo, a young female domestic worker from Côte d’Ivoire, who exchanged with someone like Chom Chaiyabut, a villager from the forests of southern Thailand.

This random sample of everyday people from the planet had access to information, translation and facilitation in order to articulate and amplify their community voices. They took their job very seriously and felt incredibly empowered by the process. ‘Previously, I felt like I was under a big tree,’ Chaiyabut said at the end. ‘Now, it’s like I am on top of the tree.’

Most importantly, together they created the People’s Declaration for the Sustainable Future of Planet Earth, a call ‘to deliver a flourishing Earth for all humans and other species, for all future generations.’ The Declaration advocated for upholding the Paris Climate Agreement – it was therefore not in opposition to classical multilateralism, but built upon it, displaying more ambition and creativity than we usually see at COP conferences. The Global Assembly, for example, called for a fair distribution of responsibilities based on historical emissions and capacity, inclusive climate action so that vulnerable countries can participate in decision-making, the inclusion of environmental rights in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, legal protection of nature against ecocide, comprehensive climate education for all, a just energy transition with support for less affluent countries, and a shared responsibility between citizens, governments and companies to ensure a sustainable future. In 12 weeks, they had achieved more than COP had in 30 years.

At the end, Chom Chaiyabut from Thailand said: ‘The ideals of the Global Assembly make me hopeful for humanity in successfully tackling the climate change crisis around the world. I am sure we can do it, as I believe we all have mutual love towards our planet.’ He was not alone in praising what had been achieved. Even the UN secretary-general Guterres applauded the initiative as ‘a practical way of showing how we can accelerate action through solidarity and people power’.

Suppose such a global citizens’ assembly were to become an integral part of the COP meetings. After a pre-conference online phase, which could involve several million participants, a random sample of 1,000 of them, doing justice to the diversity and demography of the world, would participate. And suppose they were allowed to deliberate, not just in the Green Zone where visitors and activists stroll, but in the Blue Zone, the heart of the congress, where the official proceedings take place. And suppose this assembly had access to the best available science on climate change and its causes. They would also hear from national politicians, civil society organisations, private sector actors, religious leaders and Indigenous communities. At the end, they would deliver their recommendations to the leaders of the world. Would they need almost 30 years to state the obvious, namely that we have to get out of this fossil nightmare as soon as we can? Most probably not. They would take planetary custodianship to an entirely different level, well beyond the pathetic bargaining of national and industrial interests at the annual COP conference. They would show that, above bilateral and multilateral diplomacy, another level is possible: planetary diplomacy.

The proposal to include a global citizens’ assembly at the heart of international climate diplomacy is less utopian than it might seem at first glance. Ideas in this direction are gaining international traction. That, at least, was the conclusion I got from the conference in Oxford in July 2024: ‘A Permanent Global Citizens’ Assembly: Adding Humankind’s Voices to World Politics’.

A few months later, an essay by Laurence Tubiana and Ana Toni was published, entitled ‘The Case for a Global Climate Assembly’. The authors were no lightweights: Tubiana was one of the lead negotiators of the Paris Agreement, and Toni is currently Brazil’s secretary of climate change and the main person responsible for COP30, which will be held in the Brazilian city of Belém in November 2025.

They, too, recognised that our existing diplomacy was falling short, and suggested involving ordinary people as well. They pointed to national citizens’ assemblies with randomly selected citizens in Ireland and France, and participatory processes in Brazil. It was shown that randomly selected citizens deliberate more freely and are less hindered by party interests than political elites, resulting in more ambitious and coherent recommendations.

We need spaces where the world can speak as the world on the problems of the world

Tubiana and Toni felt it was high time to bring this approach to the global level, just as Richelieu had brought the raison d’état from the local to the national level:

[W]hat we need now is … a Global Citizens’ Assembly for People and Planet, to bring citizens together from every country, not just to chart a collective path forward, but to reimagine our politics and encourage a global ethical stock-take.

They wrote that the time is ripe for this. In G20 countries, 62 per cent of citizens support the idea of citizens’ assemblies, while in countries such as Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico and South Africa, the figure rises to over 70 per cent, and in Kenya, more than 80 per cent of the population is in favour.

Courtesy Ipsos, Earth4All and the Global Commons Alliance Global Report, June 2024

Their conclusion was as obvious as it was bold:

At COP30 and beyond, we must provide a dedicated space to hear every voice, and to ensure that the transition is not only fast but fair. Failing that, we will not achieve our common goals. That is why Brazil is committed to making COP30 (in November 2025) the People’s COP, and to giving every person on Earth the opportunity to participate in shaping our common future.

It is expected that this first attempt to integrate a global citizens’ assembly at an international climate summit will face considerable challenges. While Brazil has a long tradition of participatory processes and social dialogue, it is also an oil-exporting country that in February 2025 joined OPEC+, the forum for oil producers.

This time around, the core assembly will be preceded by a large number of community assemblies worldwide. Organisations from across the globe have been involved in shaping the governance and designing the process. Particular attention is given to non-Western forms of knowledge.

In diplomacy’s third act, we need spaces where the world can speak as the world on the problems of the world. Global climate governance involves deep moral choices about the future of the planet that cannot be left in the hands of national negotiators alone. For instance, how are we going to distribute the remaining carbon budget? Can rich countries continue as before because their economies are so carbon-intensive, or should the last gigatons be given to the poorer countries who need them for their basic development?

Even more important will be the debate on geoengineering. As the planet approaches irreversible tipping points and faces the risk of a runaway climate for centuries to come, should we buy some time by spraying sulphate particles into the stratosphere to reflect the Sun’s rays? This type of solar radiation management could create an artificial volcanic winter, giving humanity a few extra years to get its act together. Is it too dangerous to attempt? Or is the greatest danger that governments might cease all other efforts once they can cool Earth by simply sprinkling dust? These are such fundamental choices for the world that a large, representative sample of its inhabitants should at least be given the opportunity to weigh in on the appropriateness of such a far-reaching intervention.

There is no shortage of major questions. Just to name a few: should humanity have a say in matters such as PFAS and microplastics, or can these issues continue to be settled behind closed doors by political and economic elites? Should the Moon be opened up for the exploitation of its minerals and solar energy, and, if so, under what conditions? And how about Mars and the growing use of interplanetary space? Who determines whether and when spatial exploration may become spatial exploitation?

The question is easy: how on earth are we going to save Earth? Do we content ourselves with quietly continuing to watch the painful spectacle of the past decades, believing that this protocol is the only one possible? Or do we draw hope and inspiration from global opinion polls and fascinating experiments that show that everyday people want so much more action and can play a crucial role themselves?

We are at a crossroads. If diplomacy is to have any relevant role in the age of planetarity, it has to update its current multilateral paradigm. Just like the bilateralism of the ancien régime was fundamentally transformed by the cataclysmic events of the Napoleonic era, the multilateral model must be structurally renovated given the catastrophic conditions of our time. Every 200 years, diplomacy needs an update. Why wouldn’t it be able to renew itself today?

The big question, then, is not whether diplomacy will change, but how. For 400 years, it served the nation-state; in the future, it will have to serve in the name of Earth. To begin moving in that direction, diplomacy must, as soon as possible, bring the voice of the planet’s inhabitants into the heart of its crucial deliberations – not to replace current negotiations, but to complement them, just as Metternich’s multilateralism once enriched rather than replaced Richelieu’s bilateralism.

At this juncture, it may be more instructive to revisit the older traditions of non-Western diplomacy

At COP or the UN General Assembly, these assemblies may become essential for contemplating the common good and the long term, offering a moral framework for future action. Ideally, their recommendations would have legal status and become an integral part of the global decision-making process. To be effective, a follow-up mechanism will need to be integrated. Inspiration can be taken from the first institutionalised citizens’ assemblies, like the one in the German-speaking community of Belgium, the first place on Earth where the elected parliament is flanked by a permanent assembly drafted by lot. Each time everyday citizens make recommendations, elected politicians are obliged to respond.

Whatever its precise form, Act III diplomacy will require a loosening of the raison d’état in favour of the raison de Terre. This may sound as visionary as Kant’s ‘federation of free states’ did in 1795, but two centuries later his idea has materialised, notably in the European Union. Moreover, the EU exemplifies how the voices of both countries and citizens can be combined in international decision-making, with its delicate balance of power between the national governments and the transnational parliament.

However, diplomacy’s third act should not overly fixate on European examples. Sufficient inspiration has been drawn from the West over the past 400 years. At this juncture, it may be more instructive to revisit the older traditions of non-Western diplomacy, largely overshadowed by the Westphalian system of sovereign states.

Classical Chinese diplomacy, for instance, centred on the notion of tianxia, ‘all under Heaven’, encompassing the entire physical world of lands, seas and mortals. Confucian values like ren (benevolence), yi (righteousness) and xin (trustworthiness) continue to inspire Chinese diplomats and may prove relevant when sketching the outline of a planetary democracy. Similarly, the Indian concept of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam, a Sanskrit phrase meaning ‘the world is one family’, could help us – it goes back to one of the Upanishads written between 800 and 500 BCE and was used as the theme of India’s G20 presidency in 2022-23. Indonesia has inscribed the traditional practice of musyawarah‐mufakat, village-based deliberation and consensus-making, in the foundational philosophy of the country’s democracy. The African philosophy of ubuntu – ‘I am because we are’ – remains a potent reminder of human interconnectedness and the universal bond between all living things. In post-apartheid South Africa, it has notably inspired new forms of justice that prioritised collective healing over individual punishment. Ideas and moral values matter, as they shape the institutions with which we work. Act III diplomacy will, therefore, need the best ideas the world has on offer, in order to succeed.

There is also an obvious need for more demographic justice. China, India and Indonesia are three of the four biggest countries in the world – together, they present more than 38 per cent of the world population. And in 2050, a quarter of the world will be African, as its population will rise to 2.5 billion. It seems about time that some of their most central philosophical and spiritual ideas help shape global politics of the future.

A number of years ago, I walked the Pyrenean High Route, an 800 km-long trail from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean, following a high course in the mountains that stays as close as possible to the French-Spanish border, the one established so long ago on Pheasant Island. As I was climbing up and down the granite and limestone border ridge, I found myself cursing more than once at the negotiators of Pheasant Island who had gladly drafted a line on the map without actually getting up there themselves. But the hike was absolutely magnificent, and gave me ample time to reflect on the beauty and the fragility of the world.

At a given point during my hike, the reality of climate change kicked in with such violence I will never forget. I was camping in front of the brutally beautiful north face of the Vignemale summit, the highest peak on the French side. At dusk, the silence of the spectacular setting was interrupted when a section of the mountain’s easternmost glacier broke loose and came tumbling down its scree slopes in a cloud of dust and stones. The sound – a raw, thunderous roar – was unearthly and deeply unsettling. That night in my tent, I struggled to find words to write down in my diary. The following days, I kept on pondering over the event during my climbs. Even if it was too early to find satisfying answers, I began to sense that there was something fundamentally wrong with a system of world politics just based on national sovereignty. If the broken Vignemale glacier had made one thing clear, it was that private vices did not lead to planetary virtues.

We have already moved from the Enlightenment to the age of ‘Entanglement’

Later at home, I came to realise that there is a certain Cartesian quality to the Western-style diplomacy that has dominated the world. Richelieu was reshaping France’s foreign policy at the same time that Descartes wrote his Discours de la méthode (published in 1637). Both placed the self at the heart of their logic. What the cogito was to Descartes was the raison d’état to Richelieu: a vantage point in the middle from which all the rest was to be deducted.

The timing was perhaps not a coincidence. Just a few years earlier, Galileo Galilei had demonstrated that, not Earth, but the Sun stood in the middle of the planetary dance. Descartes and Richelieu came up with the metaphysics and politics of self-centredness, as if something had to be compensated – from geocentric to egocentric, so to speak. Right after Earth was dethroned from the centre of the solar system, a self-centred perspective became deeply ingrained in the core of Western philosophy and diplomacy, and it has remained there until now. It continues to shape the way we deal with the planet today, from Pheasant Island to the COPs in Sharm el-Sheikh, Dubai or Baku.

Today, it is time to develop a new geocentric model – not in the astronomical sense, of course, but philosophically: a fundamental awareness that places the Earth system at the centre of our thinking and actions, and that considers the raison de Terre as the keystone of global governance. Drawing on a wide range of philosophical and spiritual traditions, this geocentric awareness can even look beyond the interests of present generations and strictly human concerns to take into account the distant future and the more-than-human life. Such a perspective was already pioneered by the Global Assembly when its members unanimously called for ‘a flourishing Earth for all humans and other species, for all future generations’. More than we might realise, we have already moved from the Enlightenment to the age of ‘Entanglement’. It is time to design a diplomacy that befits this new reality. It is time for planetary governance.