Whoosh. Our boat rocks a bit when a pink river dolphin surfaces and blows just a paddle’s length away. We’re in a low, open boat in western Brazil, a few hundred miles downriver from the borders of Colombia and Peru.

As a climate scientist at Stanford University, I’m here with colleagues at the Mamirauá Sustainable Development Reserve deep in the Amazon to build new towers for monitoring emissions of carbon dioxide and methane, two of the world’s most powerful greenhouse gases. I study methane in particular because, pound for pound, it’s 90 times more potent than carbon dioxide at warming Earth in the first two decades after release. And methane concentrations have risen faster in the past five years than at any time since record-keeping began, for reasons we’re still trying to understand.

The highest methane emissions in nature come from tropical wetlands and seasonally flooded forests – like here at Mamirauá – and they are expected to rise with warming. Mamirauá is the western jewel in a chain of national parks and reserves placed deep in the Amazon to protect biodiverse forests, and the primates, people and fish who call them home. Mamirauá includes Indigenous lands and promotes the wellbeing of the ribeirinhos – traditional peoples living in communities along the river who fish, farm, selectively cut trees, and make crafts for their livelihoods – hence its designation as a ‘sustainable development reserve’. A sanctum of water, sky, wetlands and trees, its water is rich and tea-stained. The air is redolent of mud.

Tropical wetlands yield so much methane because they are warm, wet (by definition) and low-oxygen environments perfect for growing methane-emitting microbes. But tropical wetlands and flooded forests are also the world’s least-studied ecosystems for methane emissions – and almost everything else, for that matter. They’re hard to reach and a challenge to keep instruments running in, thanks to everything from the constant humidity to rampant ants that short wires.

Tropical methane emissions are expected to increase in wetlands because warmer temperatures boost microbial activity. Our new towers will help us measure methane emissions today and provide a baseline for documenting future changes. Recent work suggests that tropical systems may already be releasing more methane caused by warming. Using satellite data, we recently concluded that higher tropical wetland emissions from the Amazon and elsewhere yielded most of the increases in atmospheric methane in recent years. The world has no way to counter such increases. You can turn a wrench to quench methane emissions in an oil field, but there is no wrench to turn for the Amazon.

The Amazon is in danger of unravelling from a combination of human pressures and climate change. Beyond deforestation, illegal gold mining is surging. Illegal mining destroys biodiverse forests and contaminates watersheds with the mercury used to harvest the gold. As a result, four-tenths of the people tested in a hundred villages in the Peruvian Amazon had dangerously high levels of mercury from eating fish contaminated with mine waste.

Human pressures are building from outside the Amazon, too, through climate change. New research shows that tropical forests are approaching critical temperature thresholds beyond which leaves will die from the heat. Such ‘tipping points’ may kill rainforests over large areas and keep them from regrowing.

An Amazon kingfisher flashes white as it rattles across the channel in front of our boat. I turn to my host, the Brazilian hydrologist Ayan Santos Fleischmann. Born in the city of Porto Alegre in southern Brazil, Fleischmann directs Mamirauá’s research on water, air and the environment. I ask him how climate change is altering Amazonia. ‘Everyone acknowledges it’s hotter and harder to work,’ he says. ‘In the past, people would go to work in the field at 2 pm. Now they need to wait till 3 or 4 pm because the heat is unbearable.’

‘But “the Amazon” is really many Amazons,’ he says. ‘We currently have what you would call a hydroclimate dipole – more rainfall north and west of us next to the Andes, and less rainfall and more drought in the lower Amazon to the south.’

‘We’re already having more rainfall and floods in the upper Amazon,’ he adds. Fleischmann’s group published a paper in 2023 showing a one-quarter increase in the maximum flooded area across the Amazon floodplain since 1980 – a 26 per cent increase in only 40 years, a phenomenon that should combine with warmer temperatures to increase methane emissions.

The other Amazons, particularly the lower Amazon, are changing too. As we float into a vast wetland that we’d marked on a satellite map, a 10-foot caiman eyes us, the slits of its pupils standing tall as trees that open into darkness. Horned screamers, or camungos, squawk their awkward calls from waterside branches as we pass, their unicorn horns bobbing. But the real stars are flocks of orange-mohawked hoatzin. These birds are unique in having claws on their wings, like prehistoric archaeopteryx, so chicks can hold on to tree branches to keep from falling in the water. Their chuffs surround us.

Hoatzin are also the world’s only flying cow, hosting microbes to ferment their leafy diet. Not surprisingly, they burp methane, too. And although, yes, I’m curious, I haven’t travelled to the bowels of the Amazon to measure methane emissions from a bird.

Ocean temperatures off Florida topped hot-tub levels – close to those suggested for cooking Atlantic salmon

Fleischmann brings me back to the risks of droughts and fires. ‘The worst Amazon droughts happen in El Niño years with warm Atlantic waters nearby,’ he says. The key ocean region that influences Amazon droughts is between 0 to 20 degrees north – roughly the belt from the equator to Cuba and southern Florida. The extreme drought triggered by the 2015-16 El Niño featured record high temperatures and killed billions of trees – turning the Amazon from a global carbon sponge to a vast carbon source. Amazon fires raged in 2015 and 2016.

And now here we are in July 2023 during my visit, as El Niño strengthens again and the tropical Atlantic is baking. Ocean temperatures off the coast of Florida topped hot-tub levels of 101°F (c38°C) – close to temperatures suggested for cooking Atlantic salmon, and the highest surface ocean temperatures measured. ‘This appears to be unprecedented in our records,’ said Derek Manzello, a scientist at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and coordinator of its Coral Reef Watch, as reefs died and health monitors warned people not to swim because of the risks of overheating and exhaustion.

The legendary distance swimmer Diana Nyad – one of the first people to swim from Cuba to Florida – wrote a piece for The New York Times, ‘What It’s Like to Swim in an Ocean That’s 100 Degrees’ (2023), in which she said: ‘Years from now, we may well remember the summer of 2023 as the beginning of an era when many of our oceans stopped serving as a glorious place of recreation.’

Because of the strengthening El Niño and the warm ocean temperatures while I was there, Fleischmann said that 2023 and 2024 could both be years the Amazon – the southern Amazon, especially – fries, dries, and burns.

His warning was prescient. In late September – just two months after I left – the region baked in unprecedented drought. Water levels in the Amazon system were lower than at any time since record-keeping began more than a century ago.

Air temperatures around Mamirauá topped 104°F (40°C) for days, and the absence of rain and clouds cooked Amazon waters in the sun. In Lake Tefé – a tributary of, and gateway to, the western Amazon – Fleischmann measured water temperatures at an astounding 105°F (40.5°C) at depths of three to six feet.

When we spoke over Zoom a few days later, he almost wept: ‘Nobody ever saw anything like this before. The first day, 25 September, I saw 10 river dolphin carcasses. That was a shock. Then two days later I saw 70 carcasses along the lake.’ One dolphin, swimming in circles, was in agony and struggling to survive. ‘We didn’t know what to do or how to help it,’ he told me. ‘If you try to rescue an animal that is already hurt, it can die from the extra stress.’

Not only was it hot and dry, but more than 7,000 fires raged across Amazonas state. People were suffering, too. Many local ribeirinhos couldn’t get to hospitals or find food or water because water levels were too low to allow boat travel. News photos displayed dead dolphins hauled onto tarps next to images of desperate people hand-digging wells for drinking water in dry riverbeds. Dead fish paved riverbanks in silver-brick roads.

Researchers from the Mamirauá Institute for Sustainable Development retrieve a dead pink river dolphin from Lake Tefé in Amazonas state, Brazil, 1 October 2023. Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters

I feel Fleischmann’s despair – plus anger I didn’t feel a decade ago. I’m sadder and increasingly discouraged about where we are now. What actions seem reasonable today look so different to me than when I began studying climate change. I never thought I would live to see the world’s weather unravel and people suffer so much for it.

Reflecting back on the places I have travelled where climate records were shattered during my visits, it seems clear we are all in danger: on my trip to the Amazon in the hottest month of the hottest year on record, July 2023, Atlantic surface waters boiled; during my visit to the Vatican in 2022, Europe’s hottest ever summer killed 60,000 people overall and 18,000 in Italy alone.

The sweltering heatwave in the northwestern United States and Canada, meanwhile, has shattered all-time temperature records. In June 2021, the village of Lytton in British Columbia set Canada’s highest temperature ever recorded at 121°F (c49.5°C) and promptly burned to the ground the next day. Two years later, while the Amazon withered, Canada suffered its most destructive fire season, worsened by unusually hot and dry conditions. By October 2023, 46 million Canadian acres burned – 5 per cent of all Canadian forests and nearly triple the amount burned in any previous year. Dangerous wildfire smoke choked people from Ottawa to Miami. A longtime wildland firefighter and Canadian fire chief surveyed the country’s destruction and said: ‘The unimaginable has to be imaginable now.’

The world’s top 1 per cent contributes more fossil carbon emissions than half the people on Earth

In the face of inaction, we’re headed for what I call the Hellocene, a time of unchecked suffering and weather calamities. If images like dolphin deaths don’t move us, perhaps heat and humidity too severe for human tolerance will. Heat like this is coming – on rare days, some coastal regions in the tropics already kiss deadly combinations of heat and humidity. Wet-bulb temperatures of 95°F (35°C) mark the upper physiological limit of human survival, when our bodies can no longer cool themselves, even by sweating. Imagine an extended heatwave where people stuck outside die from the heat – like whirling dolphins – in the shade.

We’ve been warned. The NASA scientist James Hansen gave landmark testimony to a US Senate committee in 1988 that brimmed with evidence of climate change. More than 35 years ago, he concluded: ‘The greenhouse effect has been detected, and it is changing our climate now.’ Viewing the climate carnage of 2023 and the lack of action since 1988, Hansen was even stronger: ‘We are damned fools.’

But who is the ‘we’? The top 1 per cent of the world’s population contributes more fossil carbon emissions than half the people on Earth. Climate solutions will require fairer energy use – either at lower levels of consumption than in the US or, if it comes to that, at US levels. But what would the world look like if everyone consumed at that higher rate?

A fifth of the 1.5 billion gasoline-powered vehicles on Earth are in the US, with almost one passenger vehicle per person. Europe has one vehicle for every two people, South America one for five, Asia and Africa one for every seven and 20 people, respectively. If 8 billion people on Earth owned cars at the US rate, the world would have 7 billion vehicles, almost five times the number today. No matter how green those new vehicles might be – electric vehicles (EVs), hydrogen cars or otherwise – adding 5 billion more won’t make the world more sustainable in any way. More electric cars and trucks mean more transmission lines riving the landscape, more lithium mining for batteries, and more spontaneous lithium battery fires. More biomass burning for electricity means more logging, truck trips and wilderness roads. More solar panels mean increasingly large land areas needed for harvesting electrons, less land for biodiversity and natural areas, and more mining of rare metals such as gallium and indium. What’s true for renewables applies equally to fossils, too – more fossil fuel energy means more drilling, mining, spilling, and refining.

Climate solutions start with consuming less.

Today’s unequal and unsustainable energy use dictates three families of climate solutions. The first is that we in wealthier nations consume less – to reduce global demand for products that pollute. Behaviour and individual choices drive this first group of solutions.

Our homes are apt places to begin reducing our personal methane and greenhouse gas emissions because they comprise one of the biggest sources of pollution in our lives. Not including the emissions from growing and producing our food, our homes and buildings contribute a third or more of all emissions in the US and Europe.

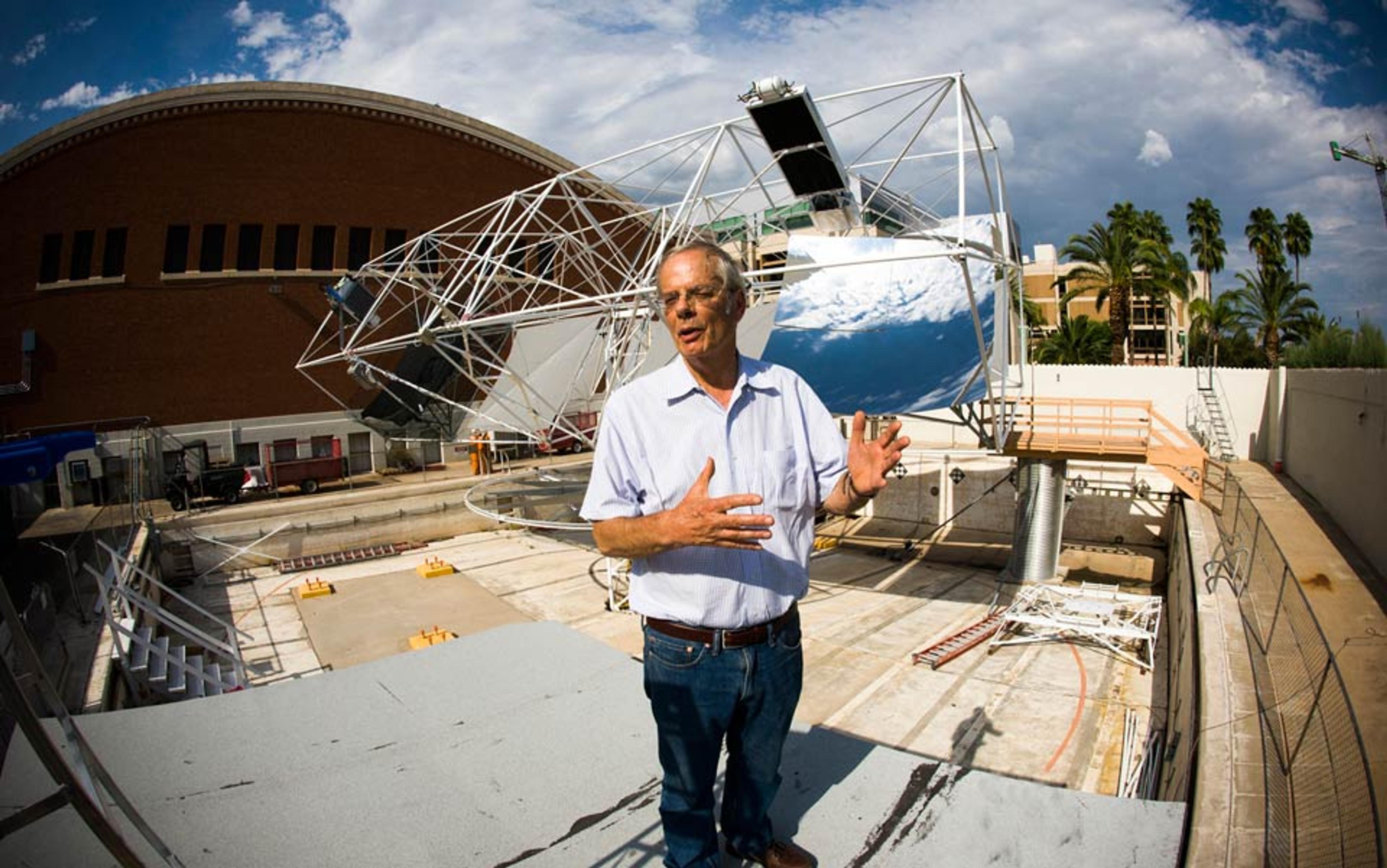

Photo by Glenn Scott/Flickr

The average US home fuelled by natural gas yields almost 2 tons of CO2 pollution per person from its gas appliances each year – before anyone steps outside to drive or travel (and ignoring emissions from producing food and any home goods bought that year). Two tons per person from gas appliances alone matches the approximate total annual fossil carbon emissions for someone living in India. By all accounts, we need to be below 1 ton of CO2 per person annually as our immediate target before quickly reaching zero or net-zero emissions. And methane leaks make the picture worse for residential gas use layered on top of the carbon dioxide emissions.

I’ve spent a decade measuring greenhouse gas emissions and indoor pollution from natural gas appliances. We’ve shown how gas stoves in the US leak methane at rates of warming equivalent to the pollution from half a million cars. Gas and propane stoves are also the biggest source of asthma-triggering nitrogen dioxide and carcinogenic benzene in many homes. We recently documented the rise of dangerous concentrations of benzene and NOx gases in home kitchens and bedrooms just by flipping a single gas burner or oven on – documenting levels well above health benchmarks set by the World Health Organization, Canada, and the US. The best way to eliminate this source of pollution from your home is to replace your gas stove with a non-polluting induction cooktop. Electric stoves emit no NOx and no benzene.

Deep down, we intuit this risk. We would never willingly stand over the tailpipe of a car breathing its exhaust. And yet 40 million American families and hundreds of millions worldwide stand over their stoves breathing in the same pollutants day after day: asthma-triggering NOx gases, carbon monoxide and the known human carcinogens benzene and formaldehyde.

Flying is almost certainly the biggest source of greenhouse gas pollution in your life

The gas industry intuits this risk, too. In 1907, the second annual meeting of the Natural Gas Association of America featured a dialogue about the dangers of breathing combustion products from gas stoves indoors, and resolved: ‘That it is the sense of this association that we condemn any appliance installed in such a manner as to permit the products of combustion to enter the room.’ The resolution passed unanimously. And yet that is exactly what people do today in hundreds of millions of homes worldwide.

The food we cook matters too. Food production yields a third of greenhouse gas emissions globally. Carbon dioxide contributes half of those food-based emissions, partly from clearing tropical forests for farmland and pastures. Beef production, for instance, drives 80 per cent of current Amazon deforestation.

Agriculture is also the largest source of methane emissions from human activities. Cows are the world’s largest agricultural methane source and emit as much methane as the entire oil and gas industry.

Dietary changes are therefore ripe for climate solutions. Americans eat four times more beef than the average person worldwide. Eating less beef would help the climate and improve people’s health. Eating a more plant-based diet, especially one rich in whole grains, fruits, vegetables and nuts, lowers the risk of heart disease, gastrointestinal cancers, type-2 diabetes, and other maladies. Even people who don’t see themselves as vegans or vegetarians can eat less beef and dairy – for their hearts and health, if not for the climate.

Once we leave our homes, changing how we travel can take another bite out of our personal emissions. We can walk, bike, take public transit or, if needed, buy an electric vehicle. Airline travel remains the biggest source of greenhouse gas pollution left in my life and the lives of most people reading this article. We may not realise how privileged that world view is. Most people on Earth have never flown once for work or pleasure, including one in five Americans. If you have any frequent flyer status, or keep track of airline miles at all, flying is almost certainly the biggest source of greenhouse gas pollution in your life. One round trip – London to New York – yields a ton of carbon dioxide pollution per traveller. That’s more carbon pollution than the average person in 50 countries generates in a year.

After we reduce demand and greenhouse gas pollution through personal changes, governments and policy-makers will need to eliminate the remaining emissions from whatever polluting industries are left, in part by pricing carbon pollution. Here, new technologies rather than individual behaviour play the key role.

I’ve met inspiring people all over the world: CEOs using clean energy to make the world’s first green steel near the Arctic circle, a medusa-scientist-CEO magically turning carbon dioxide pollution into stone, leaders transforming how we travel and eat. I met people restoring landscapes – saving forests – Amazon to Arctic, people turning ravaged peatlands back into resilient systems that one interviewee called ‘fierce, stout, and excited to be alive’.

A regulatory mandate, prices on carbon dioxide and methane pollution, or both, will be required to meet the climate challenge. When the polluter pays nothing, climate solutions will always be more expensive than free.

Finally, because we delayed climate action so long, we’ll need to hack the atmosphere, to remove or destroy greenhouse gases already in our air. I used to think that such talk distracted us from the real job of cutting emissions. It does, but the inaction of the 2010s convinced me that to maintain a safe and liveable climate, we need to develop technologies to remove carbon dioxide, methane and other gases directly from the air using everything from microbes and trees to factory arrays. And we’ll need to do it at industrial scales, running the coal industry in reverse. I wish that weren’t the cases – hacking the atmosphere is risky and expensive.

By doing all of these things – reducing personal consumption and emissions, systematically cleaning up energy-intensive industries such as steel, cement and aluminium production, and removing greenhouse gases from the air – we could restore the atmosphere in a lifetime.

The Endangered Species Act doesn’t stop at saving plants and animals. It mandates their recovery

One super-potent gas, methane, could be brought down to acceptable levels in less time than that. Methane is cleansed from the air naturally only a decade or so after its release. Because of this shorter lifetime, if we could eliminate all methane emissions from human activities, including agriculture, waste and fossil fuels – a big if – methane’s concentration would return to preindustrial levels within only a decade or two. That’s what I mean by ‘restoring the atmosphere’. Restoring methane to preindustrial levels would save 0.5°C of warming and could happen in our lifetimes.

Restoring the atmosphere will save lives. Particulate pollution from coal and cars kills more than 100,000 Americans a year. One in five of all deaths globally is caused by burning fossil fuels – 10 million senseless deaths a year – when cleaner, safer fuels are already available.

By analogy, the Endangered Species Act of 1973 doesn’t stop at saving plants and animals from extinction. It mandates their recovery. When we see grey whales breaching on their way to Alaska each spring, grizzly bears ambling across a Yellowstone meadow, bald eagles and peregrine falcons soaring on updrafts, we celebrate life and a planet restored. Our goal for the atmosphere should be the same.

At the end of our last day together, Fleischmann and I finally spy the Mamirauá research station – a two-storey houseboat roped to riverside trees. We spot a sloth, too, and drift in to track its progress. It isn’t high in the cathedral forest, it’s swimming – head up like a lifeguard – using the stroke you might expect of a sloth – a crawl. With caimans in sight, we’re pulling for the sloth as it takes forever to reach river’s edge – parroting the slow pace of climate action – and finally ascends the flooded várzea forest.

Fleischmann and I exhale when the sloth is safe, push up the channel, and rope our boat to the floating research station at river’s edge. Climbing to the second-storey balcony, I peer into the forest canopy for the final time this trip. I celebrate the army of people rising to solve the climate crisis and, eventually, to see the atmosphere restored. I’ve dedicated the past decade of my career to this quixotic idea, and I share it in hope.