It looked like a piece of driftwood floating in muddy floodwaters. But then it grew a pair of eyes that peered above the waterline. As the canoe came closer, the crocodile struck, attempting to topple it. Not knowing what else to do, the woman inside paddled toward a set of trees with branches hanging over the water. When she jumped to grab one, the crocodile leapt, too, pulling her underwater into a death roll. ‘That was the worst part of the whole experience,’ she told the news team that interviewed her in hospital. ‘The part that I still don’t like to remember.’

In February 1985, the Australian eco-philosopher Val Plumwood survived a crocodile attack on a remote river in Kakadu, one of Australia’s largest national parks. After being pulled under three times, she clawed her way up a muddy bank, making a tourniquet to stem the bleeding in her leg. For several hours, she dragged herself through the bush, dreading another attack that never came.

Plumwood would have been the 17th person to be killed (and possibly eaten) by a crocodile since 1930 in Australia’s Northern Territory. As the interviewer reminded her, there were two methods for dealing with crocodiles that kill or maul humans: captivity or death. The crocodile that attacked Plumwood had supposedly been shot and killed.

Still recovering from surgery, Plumwood told the news team that she thought this act of revenge was ‘basically pointless’. Why is it, she continued, that we think it is outrageous when another animal attacks a human being? Why is this kind of predation seen as something completely outside the naturally ordained order of things?

The interviewer paused to clarify: ‘That we’re the dominant species and should never be under attack?’

‘That’s right. We can’t accept the idea that we are part of the food chain. We eat other species all the time, we do dreadful things to other species and we see that as quite natural, but when we’re attacked by other species and they treat us as food, well, that’s unbelievable. We can’t accept that at all.’

For many centuries, European cultures have conceived of humans as radically separate from nature, formed in the imago Dei, and possessing immortal souls that transcend the natural order. But this human exceptionalism has begun to fray. Science has shown that we are, just like other animals, subject to the surging forces that constitute the natural world. We are immersed in nature. At a microscopic level, we exchange atoms with surrounding objects, and are densely populated by microbial panoplies shared with the things we touch, wear, and consume. We are not independent entities, but vast, shifting communities of living and non-living participants.

Human exceptionalism hasn’t been questioned just because it is scientifically wrong. Some thinkers have also considered how this worldview has led to ecological devastation. Pronouncements of human superiority reduce Earth and its species to mere resources for human flourishing. In that sense, human exceptionalism has enabled climate catastrophe and the wanton extinction of other species.

The solution, we are often told, involves acknowledging and re-embracing our complex ‘entanglement’ with the world. One influential book promoting this idea is Vibrant Matter (2009) by the American political philosopher Jane Bennett. ‘Some people respond to the proliferation of entanglements between human and nonhuman materialities with a desire to reenforce the boundary between culture and nature,’ she writes in the conclusion. ‘Another response is to accept the mingling …’ For Bennett, this process can be transformative. ‘I believe that encounters with lively matter can chasten my fantasies of human mastery, highlight the common materiality of all that is, expose a wider distribution of agency, and reshape the self and its interests.’

Certain forms of entanglement with the natural world can provoke a nauseating fear

From this perspective, embracing entanglement is a moral imperative: overcoming human superiority is the first step toward building a more harmonious relationship with the natural world. Similar accounts appear in bestsellers like Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass (2013), Merlin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life (2020) and Zoë Schlanger’s The Light Eaters (2024). Entanglement as an ethical ideal appears in other popular media, too, revealing a public hungry to explore their connections to the world. Documentaries such as My Octopus Teacher (2020) show humans forging friendships with other species, Japanese animations such as Princess Mononoke (1997) celebrate fragile connections with ecosystems, and big-budget Hollywood films such as Avatar (2009) tell the stories of imaginary beings who are bonded with their planet’s biosphere.

But too often this enthusiasm downplays or denies the dark side of entanglement. Connecting to the natural world isn’t always desirable. In fact, certain forms of entanglement can provoke a nauseating fear – a reaction that has been exploited in horror films. Think of the face-hugging Xenomorph from Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) as it implants an embryo inside the body of one character before bursting from his chest during dinner. Our permeability makes our bodies vulnerable to invasion by hostile agencies, including viruses, bacteria and fungi. Refusing to spray your lawn with pesticides may make you a better neighbour to the plants and animals that rely on insects, but your family might get sick from diseases those insects carry. The boundaries we draw around ourselves often keep us safe, minimise our suffering and stabilise our sense of being distinct individuals.

So, what does it really mean to embrace an entangled life? The answer is not straightforward. Truly affirming entanglement means recognising that we are vulnerable, and terrifyingly edible. This is the shocking realisation Plumwood had in 1985, when she awakened to a ‘parallel universe’ in which she was no longer just a person but also ‘food’ for a predator. In the aftermath, she contemplated the tremendous gap between these realities: ‘There is an incommensurability which shuts these two worlds off from each other. They exist as parallel universes, in different dimensions. Yet, we exist in both simultaneously.’

This raises a hard question for those who want to pursue a more intentionally entangled life: how do we embrace living as both ‘people’ and ‘food’? Can we reconcile our moral sensibilities with our immersion in the relentless processes of the natural world? This question has become urgent in recent decades. It was also, perhaps surprisingly, a point of intense concern for one of the 19th century’s greatest thinkers: Friedrich Nietzsche.

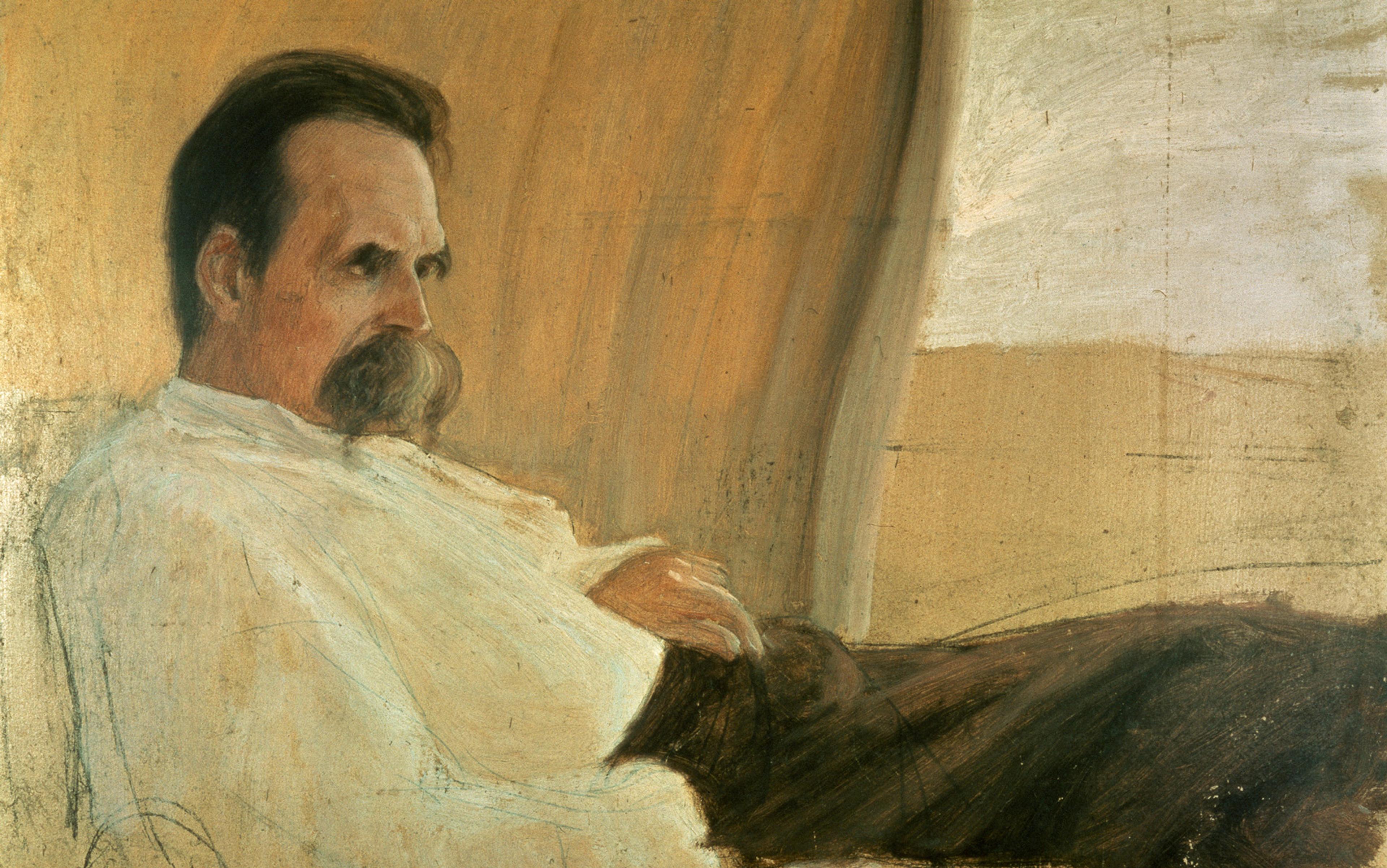

Nietzsche was born in 1844 in Röcken, a village in the Prussian province of Saxony. Educated in classical philology, he became a professor at the University of Basel at the age of 24. Despite this promising start to his academic career, his life was marked by chronic illness, intense periods of solitude, and madness. He spent much of his later life writing from rented attics in the Swiss Alps and various towns in Italy and France, often hiking in the mountains while meditating on his ideas. Those ideas were powerful, particularly his fierce and influential critiques of Christianity and modern society. Many have considered him to be dangerously radical, even nihilistic, for proclaiming ‘God is dead’ and dismantling the foundations of conventional morality. In the 20th century, however, Nietzsche would become recognised as one of the most influential philosophers of modernity, his ideas shaping existentialism, post-structuralism, psychoanalysis and posthumanist thought.

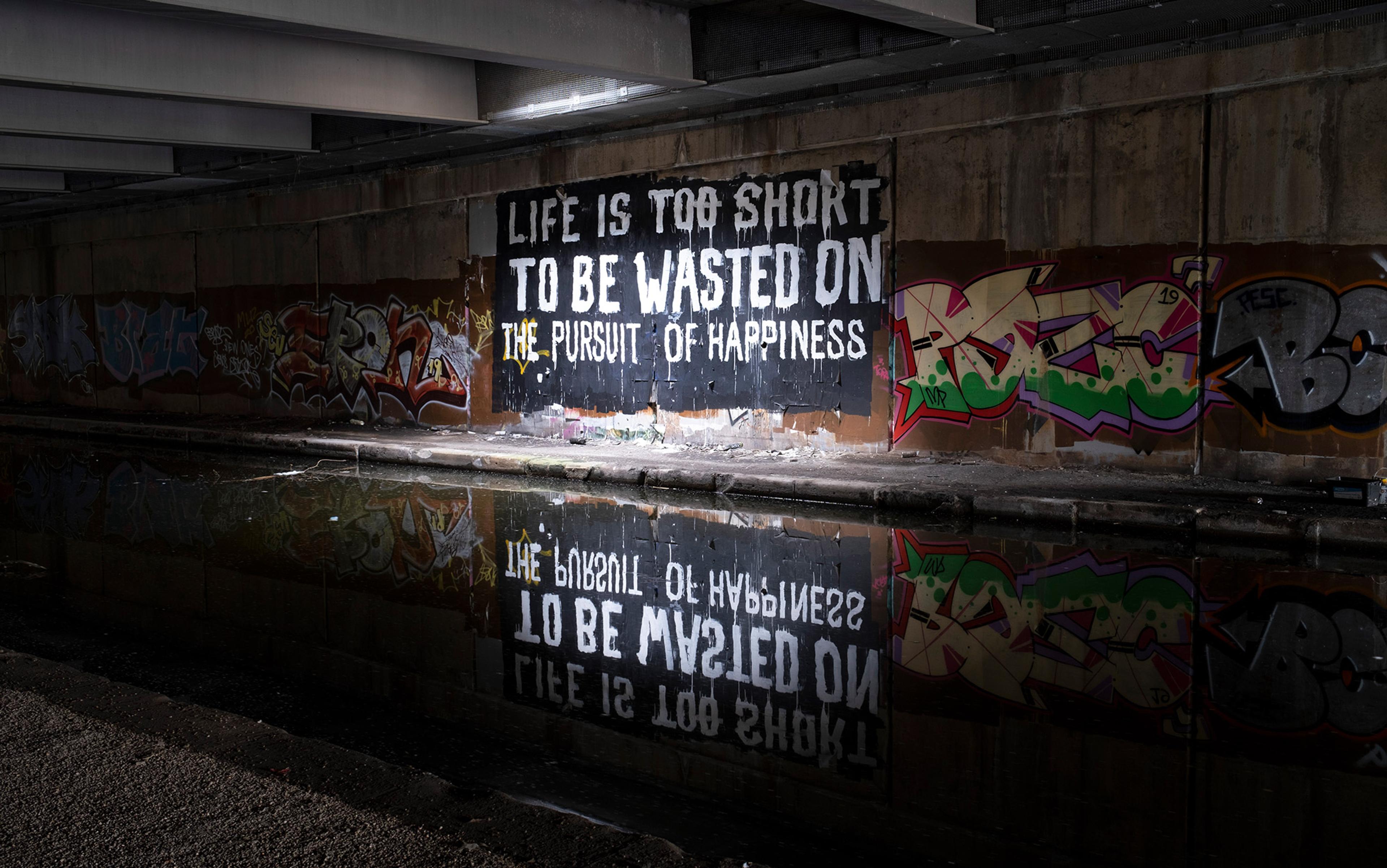

Though he is not typically considered an environmental philosopher, many of his best-known ideas bear on our relationship with the natural world – even the ‘death of God’ confronts humans with our animality. In one of his best-known books, Beyond Good and Evil (1886), he sought to translate humanity ‘back into nature’, hoping to create a healthier and more intimate relationship to earthly life. Such a translation was necessary to avoid the enticements of those who have tried to convince us that humans are exceptional, whispering: ‘You are more! You are higher! You have a different origin!’ Like other critics of the Christian and humanistic traditions, Nietzsche saw such exceptionalism as an illusion separating us from our proper place within nature. But unlike those other critics, he didn’t see human exceptionalism as a failure to live up to our deepest moral values. Instead, he believed that those values were intimately connected to the idea that we are a superior species. To overcome exceptionalism, then, we would need to overcome our inherited morality. For Nietzsche, two features of that morality stand in the way of entanglement: the ubiquitous hatred of suffering, and the comforting illusion of free will.

Suffering is necessary, it can’t be avoided, and some forms of suffering are highly advantageous

Rather than proclaiming suffering as necessarily good, Nietzsche denounced the belief – inherited from Christianity and Platonism – that suffering is necessarily bad. He argued that conflict, strife and pain were ineliminable parts of nature that we should selectively embrace, and he chastises those who would do away with suffering to promote ‘well-being’. Suffering, Nietzsche writes in Beyond Good and Evil, helps humanity grow and change:

You want, if possible (and no ‘if possible’ is crazier), to abolish suffering. And us? – it looks as though we would prefer it to be heightened and made even worse than it has ever been! Well-being as you understand it – that is no goal; it looks to us like an end! – a condition that immediately renders people ridiculous and despicable – that makes their decline into something desirable! The discipline of suffering, of great suffering – don’t you know that this discipline has been the sole cause of every enhancement in humanity so far?

Nietzsche doesn’t argue that suffering itself is good, but rather that it is necessary, that it can’t be avoided, and that some forms of suffering are highly advantageous. Moralities that characterise suffering as irrational and evil therefore deny our intimate belonging to the natural world.

Nietzsche’s second point of attack was the belief in free will. He lambasted this belief as a metaphysical illusion and rejected the idea that causal agency, ‘freedom’, belonged to individuated, rational subjects. In Daybreak (1881), the book in which his ‘campaign against morality begins’, Nietzsche questions why we accept responsibility for our waking actions, but not for our dreams:

You are willing to assume responsibility for everything! Except, that is, for your dreams! What miserable weakness, what lack of consistent courage! Nothing is more your own than your dreams! Nothing more your own work!

This is not to say that we have freedom and control in our waking lives, but rather the opposite:

Do I have to add that the wise Oedipus was right, that we really are not responsible for our dreams – but just as little for our waking life, and that the doctrine of freedom of will has human pride and feeling of power for its father and mother?

The conviction that we possess freedom reassures us that we are separate from the causal forces flowing throughout nature and permeating our bodies and minds. This belief serves the same purpose as spraying your lawn with an insecticide like pyrethroid: it erects a barrier that separates humans from the frightening reality that we are exposed to the chaotic entanglements of the natural world.

For Nietzsche, these beliefs – the idea that suffering is evil, and that individuals are free and responsible for their actions – have led us to deny our immersion in nature and to seek dominion over it. Human exceptionalism, then, doesn’t come from selfishness, rapaciousness or various other ‘bad’ moral qualities. It comes from our inherited conceptions of the ‘good’.

Embracing entanglement stands, for Nietzsche, in tension with our inherited morality. In this way, he anticipated the hard kernel of Plumwood’s insight, a century before her crocodile attack.

Understanding ourselves as ‘people’ rather than ‘food’ requires us to deny or ignore our entanglement with the natural world. However, the modern world makes this denial increasingly difficult, and in some cases impossible. While we can vaccinate against the COVID-19 virus, or avoid crocodile-infested waters, many of our permeabilities can’t be avoided. In some cases, trying to avoid them creates bigger problems.

In Rhode Island where my parents live, the average temperature has risen nearly 3 degrees Fahrenheit since 1900. This means that deer ticks and lone star ticks carrying Lyme disease, babesiosis, and Alpha-gal syndrome, or AGS (which causes an allergic reaction to meat), are now much more common than they were even 10 years ago. My own family members and friends have been diagnosed with these tick-borne illnesses, some of which can cause permanent alterations to the human body. And so, every spring, properties here are sprayed with pyrethroid to keeps lawns tick-free.

In the ocean, heavy metals are increasingly being consumed or absorbed by marine species. By eating seafood, people can accumulate high amounts of these substances, leading to lower IQs in children, impaired cognitive development, kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

Viewing the human body as will to power reveals it as a complex polity of impulses vying for dominance

We are learning that bugs, food, the climate and other features of the natural world can actively alter the function of human bodies and minds. Alongside countless ‘natural’ examples, technology also permeates human membranes (and Nietzsche would insist that technology is ‘natural’, too, having purely natural origins like everything else). Algorithms are a ubiquitous example. It’s easy to think of them as external technologies we interact with, but there is little doubt that they take up residence inside of us, moulding our perceptions, our emotions and the decisions we make from within.

Nietzsche embraced the complexity of such entanglements. Though he rejected the idea of free will, he wasn’t a determinist, preferring the idea that ‘free’ agency expressed itself in relational networks of forces struggling against one another. As part of his project to ‘translate humanity back into nature’, he described these forces as ‘will to power’, an idea meant to reconceive agency outside of traditional moralities. Viewing the human body as will to power reveals it as a complex polity of drives and impulses vying for dominance. Nietzsche writes: ‘Our body is, after all, only a society constructed out of many souls.’ This leads him to doubt whether thought or will belongs to the self or to an ‘I’ in any meaningful sense:

[A] thought comes when ‘it’ wants, and not when ‘I’ want. It is, therefore, a falsification of the facts to say that the subject ‘I’ is the condition of the predicate ‘think’. It thinks: but to say the ‘it’ is just that famous old ‘I’ – well that is just an assumption or opinion, to put it mildly, and by no means an ‘immediate certainty’. In fact, there is already too much packed into the ‘it thinks’: even the ‘it’ contains an interpretation of the process, and does not belong to the process itself.

As conscious subjects, we don’t ‘possess’ our thoughts any more than we possess freedom. Thought and agency are the products of striving, embodied desires: the ‘I’ is produced by free agency, rather than possessing it. But if we are permeable in this way and our bodies aren’t really ‘ours’ at all, it follows that our thoughts, choices and emotions originate both inside and outside our skin. So, what does it mean to call a thought ‘mine’ when bacteria, heavy metals in the bloodstream and algorithms influence what ‘I’ am? The tick, the mercury and the algorithm all think through me.

Meanwhile, trendy ‘wellness influencers’ (both Left- and Right-leaning) promote visions of purified, ever-healthy bodies. Longevity has become a new cultural obsession; Americans are told to drink less alcohol to promote longer life, while they simultaneously spend less and less time together. Work, exercise, romance and recreation all increasingly happen in isolation. These trends trade on the premiums of autonomy, independence and impermeability. Humans become our best and healthiest, we are told, by filtering out interactions with noxious, distracting outsiders.

But, as Nietzsche knew, entanglement is ineliminable. Attempts to remain pure – by ‘unplugging’ or ‘detoxing’ or avoiding forever chemicals and microplastics (and vaccines, and fluoride) – don’t work. Eventually, we will all suffer from entanglements with disease, exposure to chemicals and rapacious algorithms, though that suffering will be unevenly borne by the most vulnerable among us. The myth of human exceptionalism collapses under the vastness of our interconnections with the nonhuman world.

For Nietzsche, our task as ‘people’ is not to frantically eliminate the suffering our entanglements cause, nor to secure independence from their influences. He saw such efforts not only as vain, but as self-serving illusions complicit with the myth of human exceptionalism. As the world changes and entanglement becomes harder to deny, humanity may collectively find itself in the crocodile’s jaws: like Plumwood, we may be forced into seeing ourselves as ‘food’ as the reassuring moral world in which we are ‘people’ is devoured. What options are left to us?

Nietzsche’s vision can feel like a prophecy of extinction. In his world, nonhuman nature is cruel, but human morality is often worse. Some of his contemporary disciples, building on the related ideas of thinkers such as Georges Bataille and Gilles Deleuze, have followed this darker trajectory toward the abyss of antihumanism. Nick Land, in his early philosophical work with the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit at the University of Warwick in the 1990s, imagined a total collapse into indistinction between the worlds of ‘people’ and ‘food’, describing our emergent cultural singularity, a kind of techno-capital machine, as a swarm of dehumanising impulses working on and through human bodies to imminently reduce conscious life to cybernetic fodder. Land thinks, like Nietzsche, that the moral world of ‘people’ has always been an illusion. It is a thin disguise masking a monstrous and accelerating inhuman force of annihilation. But Land’s route leads to the brink: our options are either to cling desperately to the unravelling human world or to ecstatically abandon ourselves to the titanic vortex of our own demise.

Though Nietzsche thought there could be no moral reconciliation between the realms of people and food, he envisioned a more hopeful possibility. It involves translating ‘humanity back into nature’ by neither unconditionally affirming entanglement nor brutally reducing people to food. His solution involves imagining a new way of being ‘people’ in terms that refuse our inherited morality of ‘good and evil’.

He saw that doing so would change our fundamental self-understanding. Jane Bennett echoes this idea when she writes that embracing ‘a wider distribution of agency’ would require us to ‘reshape the self and its interests’. In showing the extent to which morality and the ‘I’ are predicated on denying entanglement, Nietzsche poses a crucial question to modern humanity: what could it mean to be ‘people’, or to be a ‘self’, without the myth of free will and the denigration of suffering? Can we move beyond morality to learn a different way of experiencing the self and the world?

Our pursuits of the good – conceived as freedom from suffering – are doomed to tragic outcomes

Envisioning posthuman life is not an easy thing to do, and many thinkers, Bennett, Plumwood and Nietzsche included, become frustratingly vague when it comes time for positive articulations. But Nietzsche’s critique of morality offers an important and hopeful insight that anyone seeking entanglement should consider.

Nietzsche doesn’t reject freedom to promote fatalism, nor does he embrace suffering to celebrate violence. Rather, he rejects these moral values because he thinks they are antithetical to life and, furthermore, depressing: they dampen the human animal’s most creative, vital and joyful elements. Our moral beliefs shield us from entanglement, but at the cost of investing our world with a nightmarish quality. We know that suffering surrounds us, and feel we should put an end to it, but we’re powerless to do so. We believe we have been given free will to pursue the good, but our actions consistently produce unintended and terrible outcomes. And, worst of all, this all seems to be our own fault; we believe that we are responsible, guilty of causing all this misery.

This worldview makes our lives into tragedies like that of King Oedipus. In trying to avoid a prophecy that he would someday kill his father and marry his mother, Oedipus unwittingly fulfils that very fate. Our pursuits of the good – as long as the good is conceived as freedom from suffering – are doomed to such tragic outcomes.

This is the worldview from which Nietzsche wanted to rescue humanity. He saw that if we could reconceive what it means to be people and unshackle ourselves from the depressing dominion of morality, we might find joy in entangled life and become better participants in the natural world.

In Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche likens this transcendence to the viewpoint of an Epicurean god, a divine being whose sphere of concern is much larger than the limited scope of humanity’s suffering, and who could therefore gaze upon the world as if it were a comedy – a joyful, laughter-inducing play. To laugh in the face of global suffering is undoubtedly cruel, even inhuman. However, the thought highlights an uncomfortable truth: in prohibiting such laughter, we make the world into a tragedy, while our pity and compassion (our efforts to mitigate suffering) only ‘serve to double these woes’. Our moral hatred of suffering only increases it. Translating humanity back into nature might therefore require learning to take joy in certain forms of suffering, especially our own.

This is hard to accept. Our morality is, after all, at the heart of so much of what we are as human ‘people’. But on the other hand, our collective striving for the ‘good’ has thus far generated an awful lot of ‘bad’ for the entangled world, and made us miserable to boot. Perhaps it’s time we tried something else. Perhaps could we even take joy in the possibility that something else could try itself through us?

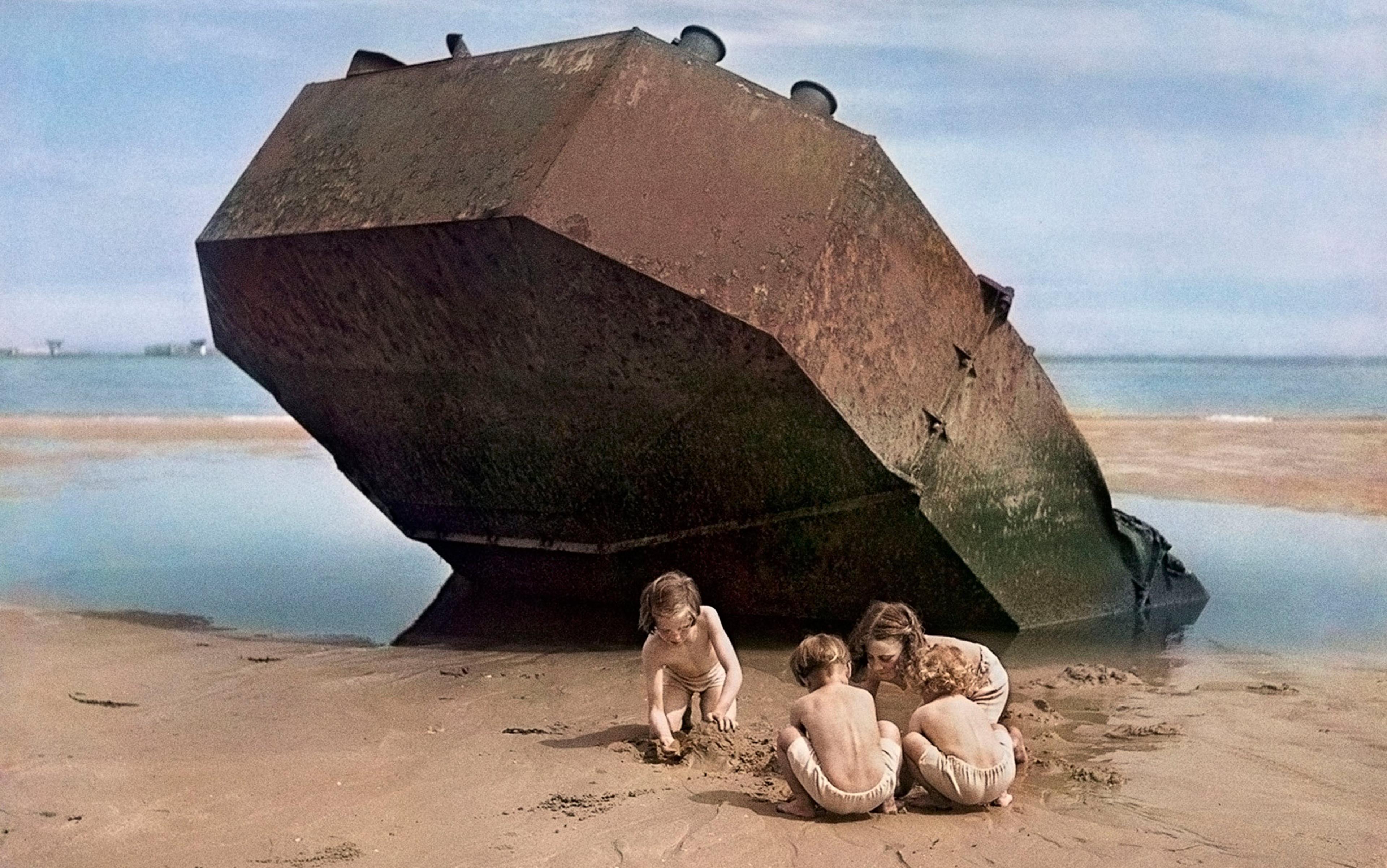

In the end, we all become food. Plumwood’s crocodile attack confirmed this reality to her in 1985. But there was a second experience that further disrupted her ideas about death. In the posthumously published The Eye of the Crocodile (2012), she writes movingly about burying her son in 1988 in ‘a small country cemetery that was also a refuge for a remarkable botanical community.’ Over time, she came to accept that her son was becoming food, too. By feeding the plants and animals that digest and compose human bodies, he was ‘being incorporated into new forms’. When Plumwood died in 2008, her choice was to be buried in a similar way. Everything that has ever lived eventually follows the same path.

Human exceptionalism drives us to avenge ourselves on predators that attack us. But we cannot avenge ourselves against every species that might feed on our bodies without implicating the entire biosphere in which we are enmeshed. To silence the fear that drives us to seek revenge, we must accept and even celebrate the fact that we might become food at any moment.

According to Nietzsche, to pity his madness, or to murder the crocodile, only increases suffering

Nietzsche ended up as food, too, consumed by the organisms in the Röcken Churchyard where his father had been a pastor. But for years before his death in 1900, he was already being eaten. In 1889, he suffered a breakdown from which he would never recover, and endured more than a decade of madness, moving between institutions and the questionable care of his family.

It is all too easy to respond to this spectacle with pity – the least Nietzschean of emotions – but he taught us to resist this moral impulse. We might wish that his life had ended otherwise, but not because we pity his suffering or his loss of freedom. To resent the forces that led to Nietzsche’s untimely undoing would be analogous to hunting down the crocodile: as Plumwood said, ‘basically pointless’. According to Nietzsche, to pity his madness, or to murder the crocodile, only increases suffering. Surely, we could seek to cure diseases like the one that drove Nietzsche mad while nevertheless finding joy in the fact that he lived precisely as he did.

In his final completed work, Ecce Homo (1908), Nietzsche wrote:

I do not have the slightest wish for anything to be different from how it is; I do not want to become anything other than what I am. But this is how my life has always been. I have never wished for anything.

Rather than regretting Nietzsche’s untimely death, perhaps we can interpret this moment of serenity on the brink of madness as Nietzsche’s way of recognising that he was already in the crocodile’s jaws. We could even imagine him paddling a canoe down a remote river in northern Australia, not dour and severe as he’s so often pictured, but singing and laughing to himself (as he reportedly did early in his madness). He rounds a bend in the rushing stream. Ahead, a piece of ‘driftwood’ opens its eyes. Nietzsche’s smile widens.