‘Everybody knows that pestilences have a way of recurring in the world,’ Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus declared to the World Health Assembly on 29 November 2021, quoting Albert Camus’s The Plague. ‘Outbreaks, epidemics and pandemics are a fact of nature,’ Tedros, the director-general of the World Health Organization since 2017, continued in his own words. ‘But that does not mean we are helpless to prevent them, prepare for them or mitigate their impact.’ Exuding confidence, he proclaimed: ‘We are not prisoners of fate or nature.’

The topic of this special session of the WHA – only the second one convened since the WHO was founded in 1948 – was to establish international negotiations to reach a global agreement on ‘pandemic prevention, preparedness and response’. The delegates passed a resolution directing negotiators to begin work on a pandemic treaty to be ready to present for approval by the 77th WHA in May 2024. But, days before the assembly meeting was due in Geneva, word leaked that the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body had failed to meet the deadline. There would be no pandemic agreement.

It wasn’t for lack of trying. The diplomats, working 12-hour days, understood the importance of their task. Having just suffered through the COVID-19 pandemic, the stakes were – and are – exceedingly clear. ‘COVID-19 has exposed and exacerbated fundamental weaknesses in the global architecture for pandemic preparedness and response,’ Tedros explained. The only way forward after so much suffering, he urged, was ‘to find common ground … against common threats,’ to recognise ‘that we have no future but a common future.’ As the co-chair of the negotiations Roland Driece put it, reaching a global agreement was necessary ‘for the sake of humanity’.

Despite a broad consensus that everyone would be better off were we globally prepared, negotiations still stalled. The major sticking points appear in Article 12 of the draft treaty, ‘Pathogen Access and Benefit-Sharing System’. Under this arrangement, countries would be required to rapidly share information about emerging pathogens, including samples and genetic sequences. But the Global South justifiably fears that their costly efforts at monitoring and information-sharing will be used to create tests, vaccines and therapeutics that get hoarded by the Global North. Negotiators from lower-income countries insist that the treaty includes guarantees for equitable access to any pharmaceutical developments, something that wealthier countries are hesitant to accept. ‘We don’t want to see Western countries coming to collect pathogens, going with pathogens, making medicines, making vaccines, without sending back to us these benefits,’ Jean Kaseya, the director-general of the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, told The New York Times.

Beyond political disputes over finance mechanisms, the equitable distribution of vaccines and treatments, and intellectual property rights, the reason for the failure to reach a global pandemic agreement boils down to the core conceptual feature of the contemporary international system: state sovereignty. Though the draft treaty is adamant in its respect for national sovereignty – it both reaffirms ‘the principle of the sovereignty of States in addressing public health matters’ and recognises ‘the sovereign right of States over their biological resources’ – nation-states have baulked at granting new authority to the WHO. Republicans in the United States Senate have demanded that the US President Joe Biden’s administration oppose the pandemic treaty, claiming it would ‘constitute intolerable infringements upon US sovereignty’. The United Kingdom government, likewise, has said it will support the treaty only if it ‘respects national sovereignty’.

In politics, there is no ‘world’; only states. For pathogens, there are no ‘states’; there is only the world

These concerns about sovereignty get to the molten core of the problem with this pandemic treaty, or really any pandemic treaty – indeed the entire multilateral system. The WHO, like every other arm of the United Nations, isn’t accountable to the world or even to world health but to the nation-states that are its members. As a result, things that would be good for ‘the world’ – like a global strategy to fight the next pandemic – often crash into firm convictions about the national interest as well as the hard-won, jealously guarded principle of national autonomy.

Tedros may believe that ‘the world still needs a pandemic treaty,’ and that it’s his mission ‘to present the world with a generational pandemic agreement,’ but he will again and again face the same problem: in politics, there is no ‘world’; only states. Compounding the problem is the fact that for pathogens, there are no ‘states’; there is only the world.

This basic mismatch between the scale of the problem and the scale of possible solutions is a source of many of today’s failures of global governance. Nation-states and the global governance institutions they have formed simply aren’t fit for the task of managing things such as viruses, greenhouse gases and biodiversity, which aren’t bound by political borders, but only by the Earth system. As a result, the diplomats may still come to agree on a pandemic treaty – they’ve committed to keep working – but, so long as the structure of the international system continues to treat sovereignty as sacrosanct, they will never be able to effectively govern this or other planetary-scale phenomena.

In our quest for control over nature’s slings and arrows, we humans have dammed rivers and made war on microbes, turbocharged grain production and ventured into outer space. We’ve domesticated animals into companions, labour and food, and figured out how to turn the fossilised remains of ancient lifeforms into energy. We’ve constructed homes and cities, razed forests and grasslands, built berms and seawalls, all to keep the elements at bay and improve our own lives. As we did all this, we took account only of human needs and desires – or rather, of some humans’ needs and desires – and ran roughshod over everything else. What’s good for fungi, flora or fauna remains irrelevant, if not deliberately negated. From a certain point of view – one held mainly by the wealthy and powerful – it seems as if Man has conquered Nature, or at any rate is justified in trying.

These pretensions of mastery have cultural as well as technological origins. Culturally, we in the West, at least, have inherited a tradition of human exceptionalism rooted in the idea that human beings, uniquely, are made in God’s image and, as the Bible says, are meant to ‘have dominion … over all the earth’. Over millennia, human civilisations have developed the tools to enact that dominion – to use nature solely as our ‘instruments’, as Aristotle put it. Technologies, from the control of fire to writing to the internal combustion engine to CRISPR, have given humans immense power over other species and Earth itself. But too often our self-image produced by the interactions of our culture and our technologies has led to the belief that this power is unbound and that we have succeeded in taming nature.

There is no possibility of human thriving unless the ecosystems that we are part of thrive

An emerging scientific consensus, however, makes clear that not only have we not tamed nature, we can’t tame nature, for the simple reason that we are part of nature. Human beings are inextricably part of the biosphere, part of Earth. These insights emerge from rigorous scientific study, not mystical reflection, and reveal our place within the biogeochemical churn of this planet. A vast and expanding infrastructure of sensors across, above and below Earth, and the networks of software and hardware that process and interpret the mountains of data the sensors produce, have demonstrated, with an accuracy and precision unmatched by previous generations, that humans are embedded in this planet’s system of systems.

What this new and growing planetary sapience is revealing is systematic wreckage. Scientists have determined that human actions (really, some humans’ actions) have pushed Earth past the ‘safe operating space for humanity’ for six of nine ‘planetary boundaries’, including climate change, biosphere integrity and freshwater change. We now understand not only the damage that we are doing to planetary systems but the damage that we are doing to ourselves as elements of those systems. The Earth sustains us, not the other way around. There is no possibility of human thriving unless the ecosystems that we are part of thrive.

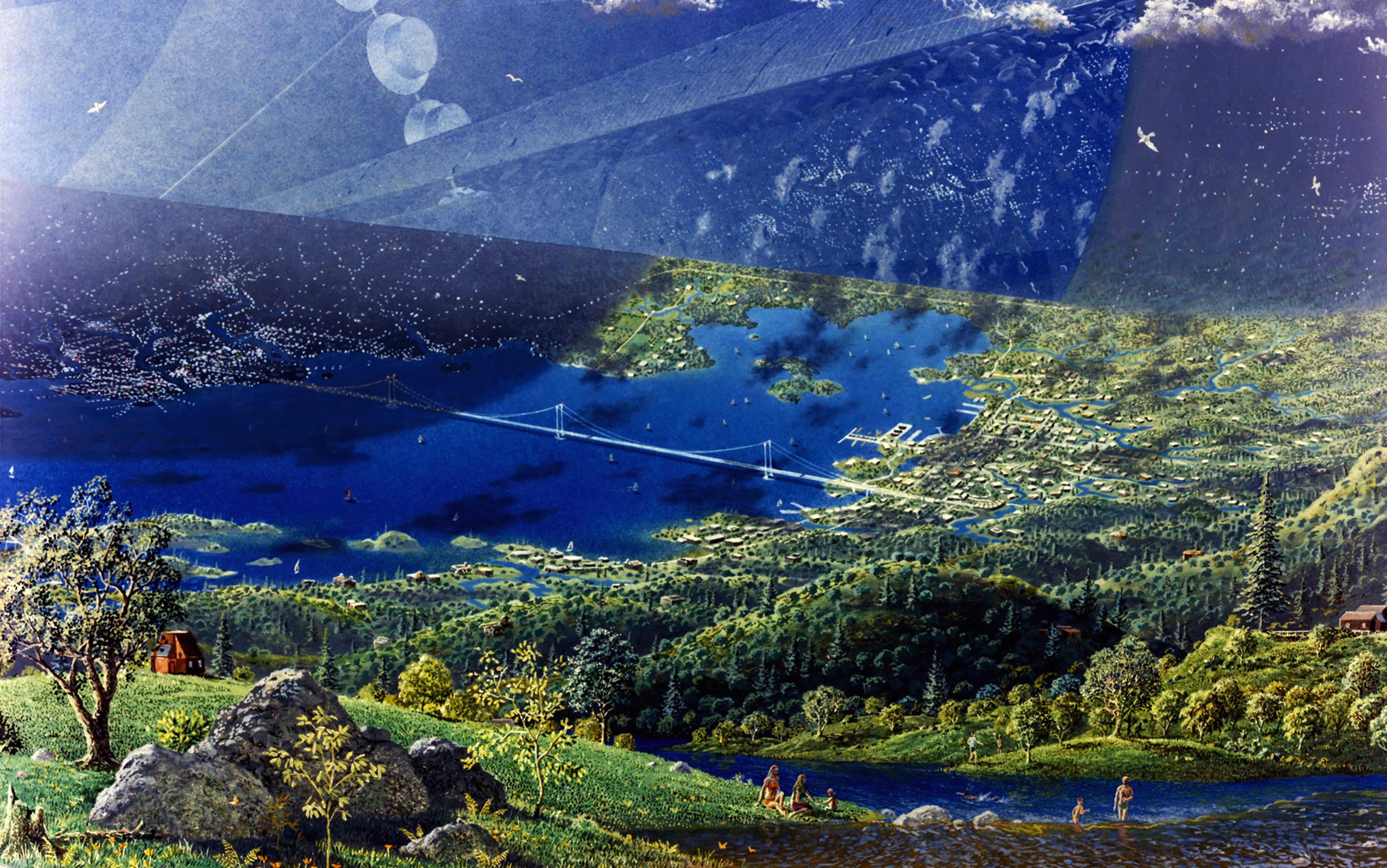

The realisation of our planetary condition may insult our narcissistic self-regard, but it also yields a positive possibility: that human flourishing is possible only in the context of multispecies flourishing on a habitable planet. The aim of habitability is meant to diverge from the now-dominant concept of sustainability. While the concept of sustainability treats nature both as distinct from humans and as existing for humans’ responsibly managed instrumental use, the concept of habitability understands humans as embedded in and reliant on the more-than-human natural world. Stripped of sustainability’s anthropocentrism, habitability focuses on fostering the conditions that allow complex life in general – including, but not only, humans – to live well. This vision of multispecies flourishing is at once generous and selfish. Expanding the circle of concern to include the multispecies menagerie is certainly more beneficent than current politics typically allows, but it is also absolutely about ensuring the survival of our species. What’s bad for them is, ultimately, bad for us. These goals – thriving ecosystems in a stable biosphere supporting human lives and nonhuman life – must be our new lodestar.

The central question of our time is: how can we achieve this?

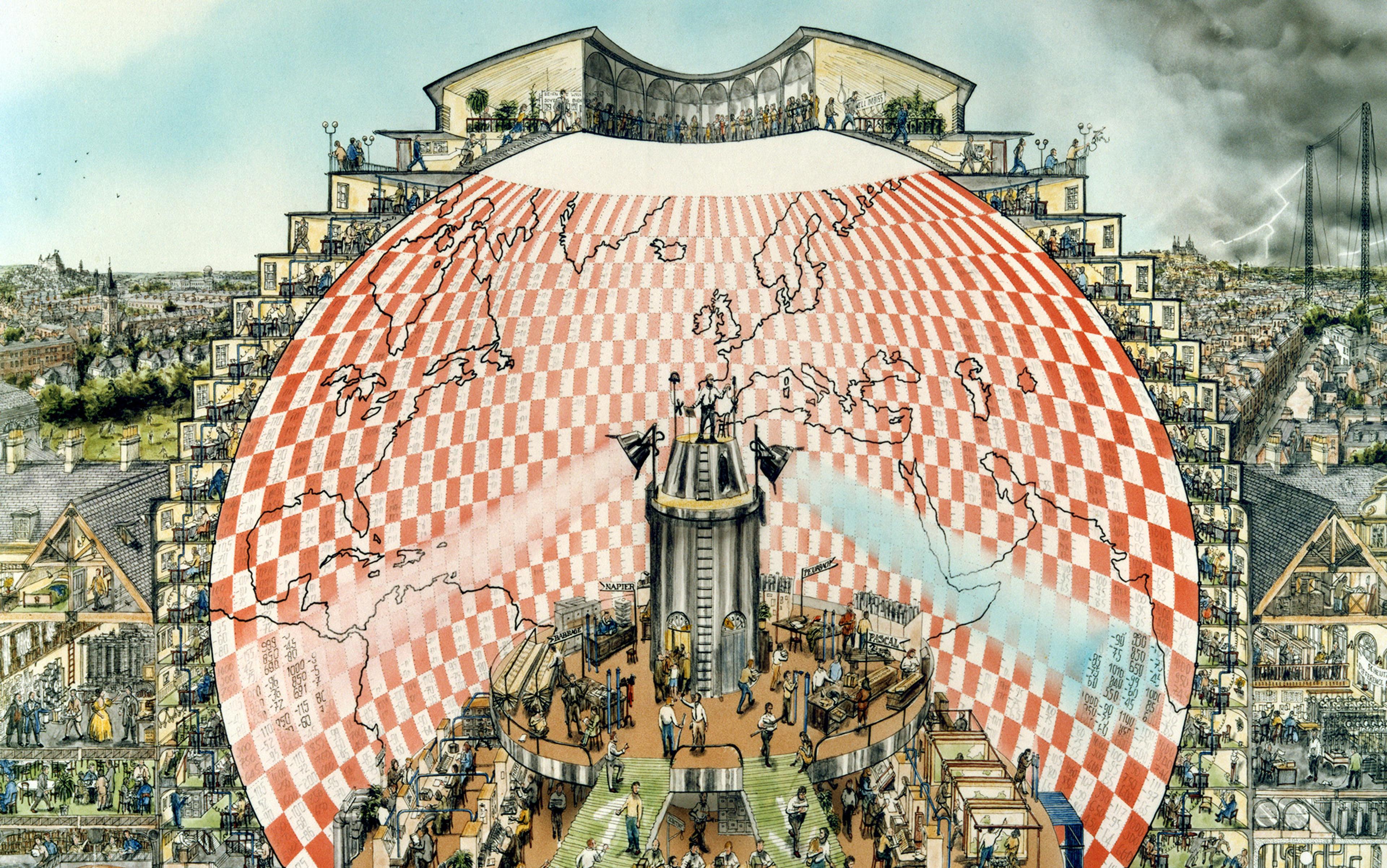

The term that scholars and policymakers initially proposed to make sense of this new knowledge is ‘global’. It is now common knowledge that Earth is experiencing global climate change, we just lived through a global pandemic, global biodiversity is at risk of its sixth mass extinction event, and this is an era of global economic, political and cultural interconnections. Yet this familiar language of the global papers over an important distinction. The word globe as it’s used in discussions of globalisation, observed the historian Dipesh Chakrabarty in 2019, ‘is not the same as the word globe in the expression global warming’. The globe of globalisation is a fundamentally human concept and category: it frames Earth from a human point of view. This globe is constructed for and by human intentions and concerns. Globalisation, the process of worldwide integration predicated on this perspective, is about the movement of people and their stuff, ideas, capital, data, and more.

The globe of global warming is a different object altogether. This concept and category – which we will now call the ‘planetary’ – frames Earth without adopting a human point of view. From the planetary, as opposed to the global, perspective, what stands out is the interlinked systems of life, matter and energy. This concept forces us to take on objects and processes that are much vaster and much smaller than we can easily comprehend, as well as timeframes far outside lived human experience. Trying to make sense of the ‘intangible modes of being’ captured by the concept of the planetary, as the anthropologist Lisa Messeri writes in Placing Outer Space (2016), is a struggle, but we have no choice. The globe of global climate change – the planet – impacts humans and is impacted by humans, but it existed before our species evolved and will be here long after our extinction.

In approaching problems such as climate change as global – that is, in a fundamental way, human – we have made a categorical mistake. For one, it suggests the goal for our action should be sustainability – an anthropocentric, global concept – rather than habitability – a multispecies, planetary concept. Moreover, the framing of problems as global suggests that they can be addressed with the tools we have at hand: modern political ideas and the architecture of global governance that has emerged since the Second World War. But planetary problems cannot. This helps to explain why decades of attempts to manage planetary problems with global institutions have failed.

The UN answers not to humanity nor the world, but the nations that united to join it

The failure to halt greenhouse gas emissions – the cause of planetary climate change – is a prime example. In June 1992, at the Earth Summit held in Rio de Janeiro, the representatives of 154 nation-states signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), committing to ‘prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system’. The international agreement was hailed as a landmark step in global environmental governance, but the very text of the treaty reveals the source of its own impotence. Alongside its plea for ‘the widest possible cooperation by all countries’ toward avoiding the ‘adverse effects’ of climate change, the treaty reaffirms nation-states’ ‘sovereign right to exploit their own resources’, including, of course, fossil fuel resources. ‘The principle of sovereignty of States,’ the UNFCCC declares, is the bedrock of any ‘international cooperation to address climate change.’

The UNFCCC, which remains the primary global body tasked with curbing climate change, doesn’t respond to the atmosphere, nor to the planet it envelops. Like the WHO, it responds instead, and only, to its member states. The member states, meanwhile, respond to their human citizens (at least, ideally). No part of this chain of authority is concerned with the planet’s climate as a whole. In this, the UNFCCC is no different than any of the other institutions of global governance. The international system is built upon the foundation of the sovereign nation-state. The UN and its many parts and agencies – from UNICEF to the Universal Postal Union – answer not to humanity nor the world, but the nations that united to join it.

Though it is better than not to have international forums to foster dialogue and cooperation among nation-states, the contemporary global governance architecture does not overcome the territorially and politically fragmented structure of the nation-state system. In fact, global governance projects and reinforces nation-state politics at a worldwide scale. International politics isn’t ‘carried out for the sake of world interests,’ remarks the political philosopher Zhao Tingyang in All Under Heaven (2021), ‘but only for national interests on a world scale.’

Managing world-scale, or planetary, problems, however, requires acting for ‘world interests’. Thus planetary problems require solutions at the planetary scale. The scale of these problems is incommensurate with our current institutional capacity to govern them. Managing problems at the scale the planet, therefore, requires creating governance institutions at the scale of the planet.

This doesn’t mean, however, that we’d be best served by a world government. To the contrary – the nature of planetary problems makes a single world state ill-suited for the task at hand. While fundamental characteristics of planetary phenomena operate at the scale of Earth, the consequences of these phenomena that we most care about occur at a local level.

Climate change, for instance, is caused by the emission of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere by specific tailpipes driving on specific roads, specific power plants operating in a specific territory, and so on. But once those rooted, place-based carbon compounds drift into the atmosphere, they become an undifferentiated part of the atmosphere’s chemical makeup. It is the overall concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere that changes the climate. Ultimately, the reason climate change concerns us, however, isn’t because of its average global effects, but because of how a changing climate manifests in specific places. What matters is how rising temperatures, increased aridity or flooding impact regions, communities and households.

No single political form is adequate for the multiscalar nature of planetary problems

From a policy perspective, this is the fundamental structure of all planetary problems: they transpire across immense, unhuman geographies and timescales but their consequences play out in particular ways in particular places (shaped by the intersection of geographic, topographic, ecological, social, economic and political conditions, and more). Take, for example, the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic – which emerged from the dynamic relationship between human beings and viruses that has shaped our species since it first evolved – was driven by the movement of SARS-CoV-2 from body to body, a process that respects neither the borders between nation-states nor the boundaries between species – other animals, including cats and civets, are susceptible to the virus. As a result, the disease spread to every corner of the planet.

The concern with the contagious disease, however, was how it affected – and, though now oft ignored, continues to affect – communities, families and individuals. The abstract vastness of a planet-scale pandemic mattered to most of us when it shuttered beloved restaurants, kept families apart, and infected friends, family or us. This interplay between scales is a critical feature for the governance of planetary problems, from stratospheric ozone depletion, atmospheric aerosol loading and space junk, to growing antibiotic resistance, biodiversity loss and anthropogenic genetic disruptions, to upended biogeochemical cycles.

What makes planetary problems so difficult to govern is that we need structures that can act at both the planetary scale and the hyperlocal scale. Nation-states are not fit for purpose. They can band together to form international organisations and they can delegate authority to subnational units (provinces, states, cities, etc), but as a political form, the nation-state is focused on that national scale. Issues that operate ‘above’ or ‘below’ the nation are peripheral to the state’s primary concerns.

The nation-state’s ill-suitedness is a major concern since it is the primary political institution today. But, in fact, no single political form is adequate for the multiscalar nature of planetary problems. What we need is plural forms of governance that can operate at all the scales necessary to tackle the problem.

Multilevel governance is already the norm around the world. Policy decisions and implementation take place at multiple levels of government and other public authorities, from neighbourhood councils up through city governments to national capitals and international organisations. But there are two crippling flaws with the existing multilevel governance architecture for the globe. First, some of the necessary scales lack governance institutions. In particular, the current system is missing planetary governance institutions, institutions that are tasked with and capable of managing planetary challenges. Second, most smaller-scale, subnational governance institutions don’t have the authority or resources necessary to address local challenges in a way that satisfies and responds to constituent desires.

Both flaws in the current system stem from the same cause: national sovereignty. While governance responsibilities are distributed among many levels, ultimate authority at present sits with only one institution, the nation-state. As a result, global governance institutions and local governments are subordinate to sovereign nation-states. Nation-states can – and sometimes do – delegate authority to international and subnational institutions, but that authority is subject to a limit: it cannot interfere with whatever the nation-state deems to be its sovereignty. The result of this constraint is that local-scale issues often aren’t governed robustly, and planetary-scale issues rarely are.

Adequately governing these many scales requires two significant changes to the worldwide architecture of governance: introducing new scales of institutions and transforming how governance authority is distributed through the system.

To simplify matters, let’s consider three primary scales of governance: local, national and planetary. Each is designed to manage the appropriately scaled issues and challenges, and together they operate as a system. Our basic vision is a structure made up of well-resourced, high-functioning institutions at all scales, from the planetary to the local, capable of governing at all scales, from the planetary to the local.

A planetary health institution would act against infectious diseases at all scales, from local to planetary

The widest scale, the planet itself, requires the widest-scale institution: planetary institutions. These, in our vision, are the minimum viable body for the management of planetary issues. We contend that each planetary problem requires its own planetary institution to govern it. As a result, a planetary institution would have defined and restricted authority at the planetary scale over a specific planetary phenomenon.

Planetary institutions, therefore, are not world government. A world state would be a single, general-purpose governance institution with broad authority over the whole planet. What we envision is multiple, functionally specific governance institutions with narrow authority over particular issues. At the same time, however, planetary institutions are not contemporary global governance. Global governance institutions today operate as multilateral associations of sovereign nation-states, which ultimately represent the interests of their member states. Unlike the WHO and UNFCCC, planetary institutions should be more directly accountable to the interests of the planet as a whole.

An example of an institution that could actually properly manage aspects of ‘world health’ on behalf of the entire world might be called the Planetary Pandemic Agency. To be effective, this planetary health institution would need the capabilities and authority to act against infectious diseases anywhere on the planet. This requires monitoring of outbreaks and enforcement of preventative measures at all scales, from local to planetary – authorities that the WHO lacks. Such an agency, moreover, must have a planetary approach to health in the sense that it understands human health as interconnected with the health of animals, ecosystems and the Earth system. So, it must be planetary not only in terms of scale but in terms of a holistic vision: that protecting our health requires protecting the planetary whole. (To its credit, the draft pandemic treaty promotes ‘a One Health approach … recognising the interconnection between the health of people, animals and the environment.’) Rather than focusing on isolated toxicities and pathogens, a planetary health institution that lives up to its mandate must keep front of mind that infectious diseases emerge from the place of humans in biogeochemical and ecological systems.

The middle scale should be governed by nation-states tasked with managing the issues fit for their scale. Nation-states thus still have a role under our vision, but that role is much reduced from the present. Nestled in a broader multiscalar governance framework, nation-states will in fact likely be better equipped to succeed at the tasks and functions for which they are appropriate, namely, distributing and redistributing economic gains and losses. Economic governance – which is a political, not a technical, activity – has historically worked best at the national scale, where political institutions can facilitate collective life between the immense abstractness of the planetary and the place-based familiarity of the local.

We must redesign the entire architecture of how and where governance decisions are made

Local governance institutions, finally, should be empowered to develop and implement robust responses to local problems and demands. They should have the resources and authority necessary to pursue policies that are appropriate to local social, political, climatic and ecological conditions, as well as to adapt agilely as those conditions change. This would represent a sea change from the operations of most local governments today. It requires well-equipped local institutions capable of managing the shared challenges of their residents. One proposal for building the capacity of local institutions is to strengthen the formal and informal ties between subnational governments. That is, to build upon the success of city-to-city networks, such as the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group (a network of almost 100 mayors of global cities committed to climate action), and establish new or augment existing transnational networks for exchange and cooperation among local governments.

Building and supporting governance institutions at all scales, from the smallest face-to-face communities to the entire Earth, provides the foundation for adequate governance at all scales. It addresses the critique made by Elinor Ostrom, a Nobel laureate in economics, of the widespread assumption among policymakers ‘that only the global scale is relevant for policies related to global public goods’. Her pathbreaking work demonstrated that that effective management of large-scale problems requires work by large-scale, medium-scale and small-scale bodies. This is what our proposed architecture sets out to provide. It offers a vision for one worldwide governance system, but not one with a unitary world governance led from one centre of power. Power, in our architecture, is dispersed among the units that need it to tackle specific problems.

Our takeaway from the revelation of humankind’s planetary condition is twofold. We need to establish new governance institutions at the scale of the planet that are able to manage phenomena at the scale of the planet. But that isn’t the only implication. We must redesign the entire architecture of how and where governance decisions are made. Dealing with planetary challenges requires both the possibility of planet-wide action and action at all other appropriate scales throughout the system. The complexity of life on this planet means that there is no one-size-fits-all institution. Rather, we must create institutional structures that foster flexibility, with multiple institutions for multiple scales, individually and collectively crafting effective governance for diverse populations seeking to thrive on one interconnected planet.

How can we organise such a complex system of governance? How should we decide which authorities should be allocated where? Our answer builds on the centuries-old principle of subsidiarity. The principle of subsidiarity states that in a multilayered governance system, larger-scale institutions shouldn’t intervene in a decision or task unless and until a smaller-scale institution cannot do it themselves. In other words, the authority to make decisions should be made at the smallest scale capable of functionally governing the issue at hand.

Subsidiarity is in direct opposition to the status quo principle for the allocation of authority, state sovereignty, which gives all authority to nation-states. To be sure, sovereign states can then decide to delegate certain authorities, if they wish, to international organisations, subnational governments or private actors, but the international system today puts nation-states in the driver’s seat. Every issue and function, regardless of whether states are well-suited to manage them, go to nation-states by default. Climate change, to take a pressing and archetypical planetary problem, is governed, in the end, by states. Even the 2015 Paris Agreement, the most important global climate accord, makes clear that the action comes from nation-states: ‘Parties shall pursue domestic mitigation measures, with the aim of achieving the objectives of such contributions,’ the diplomats wrote, leaving goal-setting and enforcement to each state.

By contrast, subsidiarity understands that while states are good for some things, they aren’t good for everything. States should have authority over the issues that fit them, but authority over other issues should move to institutions at other scales with a better fit. At the centre of the principle of subsidiarity is the message that in a diverse world there cannot be just one right answer.

Applying subsidiarity with our dawning recognition of our planetary condition generates a new principle for the allocation of authority: planetary subsidiarity. Planetary subsidiarity is the principle that we offer for allocating authority over an issue to the smallest-scale institution that can govern the issue effectively to promote habitability and multispecies flourishing. The principle provides a tool for assessing how to simultaneously address planetary challenges, such as pandemics and biodiversity, while at the same time maximising local empowerment.

Local officials should have authority over the how, not the how much

How might this principle apply in practice? Consider again the case of climate change. The first thing to acknowledge is that climate change is a quintessential planetary issue. Greenhouse gas emissions that take place anywhere have an impact everywhere. It doesn’t matter if carbon is burned in central Los Angeles or rural Laos, once it enters the atmosphere it has consequences for the entire Earth system. As a result, the smallest-scale jurisdiction that can effectively mandate climate mitigation must encompass the whole planet. Yet that doesn’t mean that a planetary institution tasked with governing carbon emissions would take charge of the entire process. Instead, a planetary climate governance institution would take only high-level decisions – about, say, the maximum permissible carbon budget for the planet each year – and then turn over the implementation to smaller-scale institutions. The planetary institution, in other words, makes only decisions that must be made at the planetary scale in order to be effective.

Nation-states would receive the planetary mandates on greenhouse gas reductions that must be met and then develop national policies for achieving them. Given the distributional consequences of these decisions across sectors and regions, the nation-state – which is the only political institution in history that has succeeded in meaningful economic redistribution – is best positioned to act. National politics, we believe, is the best site for hashing out questions like: should certain sectors or regions be compensated for losses? Or, who should pay for these changes?

After nation-states distribute the costs and benefits of climate mitigation across their society and economy, it should be up to local-scale institutions – regions, provinces, states, municipalities, villages, neighbourhoods, and the like – to determine the details of implementation. This is because local institutions are best placed to respond to local concerns, place-based affordances and constraints, and political, cultural, climatic and ecological conditions. It should not be up to localities, with particular economic interests or political preferences, to decide whether to reduce greenhouse gas emissions or by how much, but they should determine how to meet those reductions. Local officials – preferably working in networks with others facing similar challenges – should have authority over the how, not the how much. (Though this applies only to minimums; we encourage implementers to exceed their mandated reductions.)

Subsidiarity helps us to determine which of these institutional scales should have what authority over climate mitigation. It is a tool for aligning scales, functions and authority in an appropriate manner for promoting habitability and multispecies flourishing.

Shifting our conceptual toolkit from the global to the planetary will take time and great effort. But it is nothing compared with what it will take to transform our political system from one founded on the sovereign nation-state to one rooted in planetary subsidiarity. It would represent a revolution in the governance of the world – and we do not have a map for how to get there. Change must come the way it always comes, through new ideas and political struggle. Beyond that truism, however, we do not pretend to see a path for such a radical transformation of the basic structures of politics and governance.

In this, we find ourselves in good company. Even ideas that eventually succeeded in transforming systems of governance often took many decades and even centuries to be adopted. The idea behind the League of Nations (established in 1920) and the UN (established in 1945) lies with Immanuel Kant’s notion, from Perpetual Peace (1795), that ‘The law of nations shall be founded on a federation of free states.’ Forty years later, in his poem ‘Locksley Hall’ (1835), Alfred, Lord Tennyson could dream of ‘the Parliament of man, the Federation of the world’ where ‘the common sense of most shall hold a fretful realm in awe, / And the kindly earth shall slumber, lapt in universal law.’ But it took the cataclysm of the First and the Second World Wars to move this idea from the minds of philosophers and pages of poets to actual political institutions.

Crises, like world wars, are often the midwife for institutional change. Major changes to governance structures typically occur during or in the aftermath of disasters that push the existing institutional order to or past its breaking point. It’s a tragedy of politics that these changes generally come too late – that the crisis itself is what makes ‘impossible’ proposals finally seem not just reasonable but necessary. The science-fiction novel The Ministry for the Future (2020) by Kim Stanley Robinson offers one scenario where a devastating heatwave killing tens of millions of people leads to the establishment of a creative new governance structure. It isn’t difficult to imagine additional calamities for this planet.

We can’t predict what the galvanising catastrophe might be that brings about new systems of governance. We must focus our efforts instead on defining a clear perspective on what planetary governance could and should be. Holding such a vision in our minds may make it more possible to take advantage of the crisis that will all but inevitably arrive given the inadequacy of the current system. As we enter a period of not just geopolitical but geophysical uncertainty, calibrating our North Star – our vision of where we want to head – will be more important than ever.