For students of Greenfield University in northwest Nigeria, 20 April 2021 was like any other day. Muslim students observing Ramadan prepared to break their fast with iftar in the company of friends, many walking in the warm evening from the dormitories or the library to the cafeteria. Then, at about 8:15 pm, gunshots rang out. For some, the sound was not all that perturbing since the school, situated on a hill, was close to a major highway where armed robbers frequently attacked motorists. But this time was different.

Armed men, some in camouflage so that students would mistake them for military personnel, rounded up 23 people – 18 students and five staff – took their phones and herded them into the bushes. Some female students were half-dressed. Many had no shoes on. They trekked for hours before arriving at waiting motorbikes. Driven in twos or threes, they were brought to a camp where other kidnapped Nigerians were held.

Three days later, the kidnappers told parents that they had a message for them: the remains of Dorathy Yohanna, Precious Nwakacha and Sadiq Yusuf Sanga had been left on the side of a road.

Yohanna, a third-year student of political science, turned 23 a few days before she was kidnapped. The night before her death, she cried and prayed, fretting over her mother’s reluctance to let her go back to Greenfield due to security concerns. Nineteen-year-old Nwakacha, in her third year of accounting, was outspoken and articulate, which was why her classmates thought she was a good choice when she was purportedly selected by the kidnappers to take a message to the parents – they knew she would be a good representative. Sanga, who was in his third year of a cyber security course, woke the morning he was killed to share his dream: three people were going home, and he was one of them.

In Nigeria, there are two popular aphorisms related to sleep: one is ‘When you wake up is your morning’, the other is ‘You cannot wake a person pretending to be asleep.’ Though I did not know the details when I heard the news that three of the students kidnapped from Greenfield had been killed, their deaths were a morning of sorts for me.

Greenfield was not an anomaly. Schools are soft targets for terrorists and mercenaries, and this kidnapping was not more horrific than the murder of 59 students at the Federal Government College of Buni Yadi in 2014. My distress came from the peculiarly exploitative nature of the Greenfield kidnappings. The attack on Buni Yadi was ideological terror, not a negotiation for money: the kidnappers, in this case, demanded the families of the students pay a ransom of 800 million naira (around US $2 million). The average income of Nigerians is $190-$355 a month.

Channelling the desperation that I imagined the families were feeling, I reached out to two feminist activists, Olabukunola Williams and Chioma Agwuegbo, to find out what could be done. It was unfathomable that Nigerians, especially Nigerian women, would not be mobilising in response to this. It was time for us to wake up.

Williams, Agwuegbo and I developed a plan to respond to the Greenfield kidnappings: mobilise women, as influencers in their homes and communities, in order to organise Nigerians to demand that the federal government deliver on its responsibility to ‘Secure Our Lives’ – which became the name of our campaign. Our goal was to force the government to acknowledge the toll kidnapping was taking on Nigerians and to bring an end to what had become a terrifyingly profitable industry.

We were left with one enduring question: why did the campaign fail?

Six weeks after we started, the campaign received donor funding. By then, there were reports that some of the kidnapped students were gravely ill, and two more had been murdered: Feso Osunlalu, a third-year student of international relations, and Shaheed Abdulrahman, a first-year student who had been kidnapped the very day he started at Greenfield. But, on 29 May 2021, all the survivors of the Greenfield kidnapping were released after a ransom of 150 million naira (around $375,000) was paid, together with the delivery of eight new, fuelled motorbikes. Some parents, still in debt today, had to sell properties, crowdsource and borrow to make up their contributions to the ransom. Neither the Kaduna state government nor the federal government were involved in the negotiations or tried in any way to alleviate the financial burden on parents.

From the Secure our Lives campaign

Though relieved by their release, we carried on with the campaign because kidnappings at schools continued to occur. We began to put together a coalition of feminist, civil society, media and faith-based organisations that were involved in security, gender equity, human rights protection, and access to education. We brainstormed on how best to mobilise the public and capture the attention of the government. How could we get people to wake up? In addition to a day of mass action on which Nigerians would make noise at a set time of the day, reminiscent of banging pots during the COVID-19 pandemic, we planned to incorporate poetry and public installations to raise awareness about the human costs of kidnapping. (One poem began: ‘How much blood will this land drink before it says enough?’) We also published a ‘red list’ of Nigerians who had been killed or were unaccounted for from kidnapping and disappearances.

The day of action, 28 July, arrived, but the impact was not even close to what we had hoped to achieve. We continued advocating by hosting live audio conversations on X/Twitter Spaces, and anchoring our engagement to global recognition days such as International Day of the Girl Child and 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence. By the end of 2021, the campaign had petered out. We had not succeeded in waking up any significant number of Nigerians, and there were funds to spare. We were left with one enduring question: why did the campaign fail?

My reflections about this campaign over the past few years have been shaped by observing other attempts at organising, as well as by reading works on the nonprofit world, also known as the ‘third sector’. Anthea Lawson’s The Entangled Activist: Learning to Recognise the Master’s Tools (2021) and Issa Shivji’s Silences in NGO Discourse: The Role and Future of NGOs in Africa (2007) both explore and critique, in different ways, individual and organisational activism. Shivji, a leading expert on law and development, identifies NGOs (non-governmental organisations) as handmaidens of neoliberalism who replace a degraded state that is no longer capable of providing social goods and welfare. NGOs pretend to be ‘pro-poor’ while maintaining the capitalist, globalised hegemony that creates so much poverty.

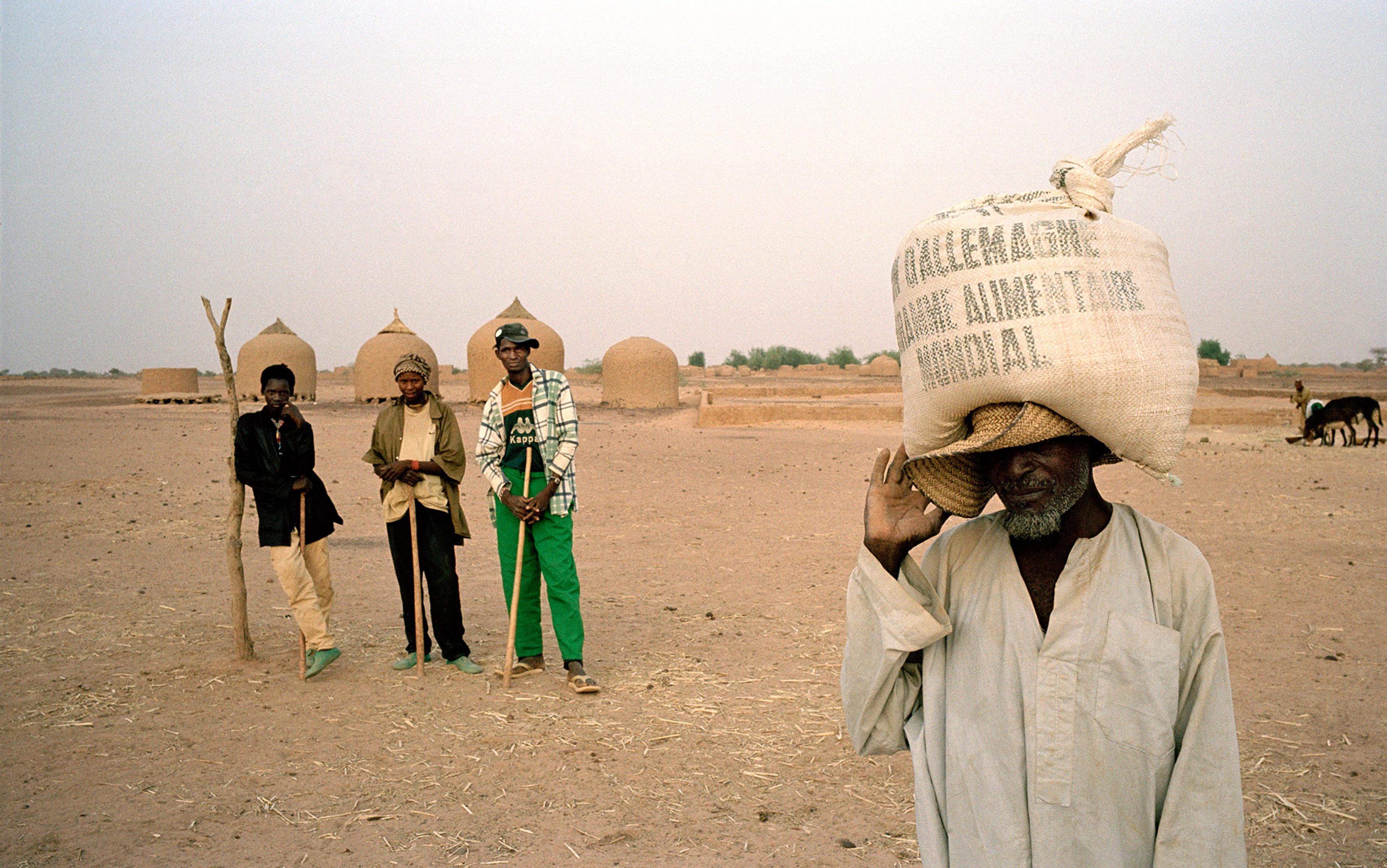

Adopting some of Shivji’s criticisms of NGOs as a framework for assessing the Secure Our Lives campaign has been useful for processing my disquiet about NGOs and the state of organising in Nigeria today. One critique is that activists try to change the world without understanding it: ‘how can you make poverty history without understanding the “history of poverty”?’ Shivji asks. Indeed, how could we successfully demand that the government secure our lives without understanding the nature of the state and the sources of insecurity? Investigating the roots of insecurity in Nigeria aligns with Shivji’s observation about the NGO space that geopolitical realities are all too often ignored. For our campaign, the geopolitical realities were highly complex, with the politics of West Africa and the Sahel largely stemming from the Cold War, foreign military bases and their implications for sovereignty, the proliferation of illegal arms, a decades-long conflict with jihadists in northeast Nigeria, and the impact of global warming on traditional economic activity. All of this needed to be taken into account but, in 2021, we were reacting to an immediate emergency. We did not have time to build the necessary theoretical knowledge about the extractive, neoliberal nature of the Nigerian state and the influence of geopolitics.

In a neoliberal, extractive state, where the majority earn a daily wage, participating in civic engagement is a luxury

On the other hand, it must be noted that my fellow organisers and I live these geopolitical realities. And, as university graduates and activists working on gender equality, governance and social justice, we are already grounded in the relevant theory and prepared to build our organising framework on our knowledge. But that is not always the case for many organisers. Courses on critical thinking were stripped from university curriculums in Nigeria in 1986 at the height of the president Ibrahim Babangida’s struggle with student unions, who were protesting the conditions of the ruinous Structural Adjustment Programmes (a number of neoliberal economic reforms forced, by the Bretton Woods institutions, down the throats of developing countries in the Global South as the magic tonic for development). This reality is arguably mitigated by the fact that philanthropies are increasingly led by people with doctorate degrees and the NGO world has a healthy supply of intellectuals. The questions remain: is Shivji right to claim that intellectual curiosity and theoretical frameworks are missing from activism? Whose theorising is required to demand a better society?

These questions are connected to the silence of the people in the communities that our campaign intended to help. Shivji’s argument is that the voices of the majority are neglected in elite approaches to development, advocacy and organising. Local wisdom and knowledge are too often sidelined. Although it might have been a novel position in the 2000s when Shivji made this observation, it is conventional now that movement-building and social justice advocacy need to be bottom-up and organic. In other words, those versed in ‘foundationese’, as the social commentator Dwight MacDonald termed it in 1956, are today implored to get out of the way. The legitimacy of campaigns requires grassroots representatives to be part of the conversation. Inclusion strengthens planning. However, the reality is that in a neoliberal, extractive state, where the majority earn a daily wage, participating in civic engagement is a luxury. This is why civil society often pays people to participate and protest. Maybe the challenge is not so much that the elite are doing much of the organising but that they are trying to organise without clear ideological values.

On the politics of aid, Shivji points out that funding and aid create dependencies within civil society and make it harder for people and institutions to collaborate. This was our experience. Once it was known that the campaign had funding, there was an expectation that we would distribute funds to mobilise women in the typical fashion: pay to protest. But that was precisely what we did not want. This caused a few organisations to withdraw from the campaign.

The recent suspension of aid from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) puts arguments about dependencies in focus. As one of Africa’s top recipients of US foreign aid, estimated at $1.02 billion in 2023 alone, the suspension has sparked major debates in Nigeria about the politics of aid. Some blame international aid for dulling and dissipating civic dissent and lowering citizens’ expectations of government to provide public goods. Others argue that aid is a form of repayment of the debt owed from colonialism, neocolonialism and neoliberalism. Still others insist on acknowledging the positive impact of aid, particularly on public health services, while a small fraction of people point out that the US is the biggest beneficiary of its aid because it builds global soft power and supports US businesses and organisations. Of USAID’s total contract spending in 2021, almost $5.4 billion out of $5.5 billion of went to US bidders.

We experienced subterfuge, competition for visibility and recognition, co-option and infiltration

Because, in the civil society space, people always follow the money, our plans for Secure Our Lives became politically fraught by virtue of funding and focus. As the feminist activist Almut Rochowanski writes: ‘Money is never “just money” … it is power incarnate.’ By deciding not to spend on mobilising citizens to join campaign activities with transport or lunch allowances, we partly sealed the failure of the campaign. But we were not going to follow industry norms and organise people by paying them. Instead, we wanted an organic campaign – like Bring Back Our Girls, launched in response to the kidnapping of 276 schoolgirls in Chibok in 2014, where people went to rallies and sit-outs (the movement’s term for sit-ins) because of shared humanity and experience, not because they had been promised the standard 1,000 naira ($2.50).

Strategy sessions at Secure Our Lives became battles about representation and identity. The pathologies of organising in a traumatised country, where power is exercised through bribery, spying and the weaponisation of identity – no matter if you’re running the government or a civil society organisation – soon became evident. We experienced subterfuge, competition for visibility and recognition, co-option and infiltration. In this, Shivji is right that NGOs too often disregard the existing power structures around which societies are organised. In hindsight, our attempt at drawing in the Catholic Women Organization (CWO) and the Federation of Muslim Women Association of Nigeria (FOMWAN) was misplaced and mishandled. Misplaced because religious organisations in Nigeria tend to defend the status quo and eschew anything radical. I might have botched our chances of signing up CWO by leading that engagement. As a Muslim from Middle-Belt Nigeria, I was probably not the best person to build an alliance with Catholic women. Then again, I was not successful with FOMWAN, so being of the same religion did not help either.

Our campaign barely made a dent in the consciousness of the working-class women we claimed as our primary target. Is the daily wage earner, the one civil society pays to attend meetings and protests, the same person that Shivji expects to lead organically? The women outside the formal NGO sector who took part in the campaign were largely affiliated with civil society organisations working in urban and rural areas. Were we preaching to the converted or were our messages unwittingly designed for them? Whatever the case, we could hardly say that educated, elite women supported the campaign in larger numbers than working-class women.

Despite the failure of the campaign, I’m left with two final questions: why was that fateful day in April, when the kidnappings took place, my morning? And why couldn’t we wake up more people?

The answers might be linked. I have had several mornings where I’ve been shaken awake by events and a sense that if we do not force government to act in the way that it is supposed to, it never will. I realise now that, for what might be a majority of Nigerians, the government does appear to act exactly in the way it is supposed to. So complete is the government’s abdication of its responsibilities that many have no concept that a government is supposed to provide public goods.

My orientation towards liberal, representative democracy – one based on a social contract in which I, as a taxpayer and voter, can demand accountability from my elected representative – is not the reality for many Nigerians. As a primarily resource-based economy reliant on extraction and trade of raw mineral resources, our government revenue does not depend on the wellbeing of Nigerians, and because the tax system is informal, for the majority there is no sense of a social contract.

I had been unable to explain the inertia of citizens, uncorrupted by donor funds, who presumably had aspirations for a better society. But this was not inertia. Those who want better security are not demanding anything from a government of which they have no expectations. Instead, they are hiring vigilantes and terrorist groups like Lakurawa to protect them.

As the economic situation in Nigeria has worsened, kidnapping has become big business

Within the first three months of 2025, at least 537 Nigerians were kidnapped. Despite generous defence budgets ($4.47 billion in 2021, up to $5.13 billion in 2024) and global support to tackle insecurity, Nigeria has remained among the top 10 countries most impacted by terrorism since 2011. In 2015, when Muhammadu Buhari was sworn in as president, it was ranked second globally for impact of terrorism. By 2021, Nigeria’s rating had improved by three places but, while terrorism declined, kidnapping rose.

Kidnapping is only one cause of insecurity in Nigeria. Cattle rustling, armed robbery, terrorism, gang violence, illegal gold mining, secessionist movements, police predation, crude oil bunkering and drug smuggling all exist across the country, feeding into each other. It is possible, as security analysts report, that kidnapping funds transnational organised crime, and there is anecdotal evidence that, as the economic situation in Nigeria has worsened, kidnapping has become big business. The recent rise in the kidnapping of medical personnel is an indication that the kidnapping industry is evolving, requiring the services of doctors and nurses for kidnap camps. Insecurity is a result of decades of steady, near-complete abdication of governance by bureaucrats and politicians. It is also about industrial capitalism, identity politics and extraction. It is about Nigeria, Africa’s place in the world economy, what we can and cannot produce, who governs us and why. It is about our elections, politics and lack of public accountability. It is impossible to address insecurity as a single issue.

Nigeria has an enormous number of NGOs – around 200,000 – but society is less organised. Typical donor funding for programmatic activities is unlikely to provide the critical requirement for successful organising: time. Some might say there is a dissonance in expecting grants to fund organising. If many Nigerians have given up on the idea that government owes them a duty of care, information alone cannot wake them up. Without an anchoring ideology or philosophy that provides values around which people identify and organise, appeals to enlightened self-interest and an assumption that ‘we all want to be secure’ will never be enough.

However, mobilising a critical mass of citizens is still one of the few ways to exert pressure to reform systems and structures – especially with the global regression in democratic values and institutions. As civic spaces constrict and social media algorithms deepen polarisation, reaching into the history of organising in Nigeria and investing in new models are more necessary than ever.

In 2011, the political scientists Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan, reviewing resistance campaigns from 1900 to 2006, put forward a magic number: 3.5 per cent. According to their research, that’s the critical mass required to ‘shift’ an issue in any given society. In Nigeria, that means 8 million people. That’s a lot of people to wake up at the same time.