Assisted dying is now lawful under some circumstances, in jurisdictions affecting at least 300 million people, a remarkable shift given that it was unlawful virtually everywhere in the world only a generation ago. Lively legislative debates about assisted dying are taking place in many societies, including France, Italy, Germany, Ireland and the United Kingdom. Typically, the question at hand for these legislatures is whether to allow medical professionals to help individuals to die, and, if so, under what conditions. The laws under debate remove legal or professional penalties for those medical professionals who help individuals to die.

Having conducted research into the ethics of death and dying for more than a quarter of a century, I am rarely surprised by how the debates unfold.

On one side, advocates for legalised assisted dying invoke patients’ rights to make their own medical choices. Making it possible for doctors to assist their patients to die, they propose, allows us to avoid pointless suffering and to die ‘with dignity’. While assisted dying represents a departure from recent medical practice, it accords with values that the medical community holds dear, including compassion and beneficence.

On the other side, much of the opposition to assisted dying has historically been motivated by religion (though support for it among religious groups appears to be growing), but today’s opponents rarely reference religious claims. Instead, they argue that assisted dying crosses a moral Rubicon, whether it takes the form of doctors prescribing lethal medications that patients administer to themselves (which we might classify as assisted suicide) or their administering those medications to patients (usually designated ‘active euthanasia’). Doctors, they say, may not knowingly and intentionally contribute to patients’ deaths. Increasingly, assisted dying opponents also express worries about the effects of legalisation on ‘vulnerable populations’ such as the disabled, the poor or those without access to adequate end-of-life palliative care.

The question today is about how to make progress in a debate where both sides are both deeply dug in and all too predictable. We must take a different approach, one that spotlights the central values at stake. To my eye, freedom is the neglected value in these debates.

Freedom is a notoriously complex and contested philosophical notion, and I won’t pretend to settle any of the big controversies it raises. But I believe that a type of freedom we can call freedom over death – that is, a freedom in which we shape the timing and circumstances of how we die – should be central to this conversation. Developments both technological and sociocultural have afforded us far greater freedom over death than we had in the past, and while we are still adapting ourselves to that freedom, we now appreciate the moral importance of this freedom. Legalising assisted dying is but a further step in realising this freedom over death.

I have sometimes heard arguments that assisted dying should be discouraged because it amounts to ‘choosing death’. That is inaccurate. We human beings have made remarkable progress in extending our lives, but we remain mortal creatures, fated to die. Death has, in a sense, already chosen us. Some enthusiasts believe that we are on the verge of conquering death and achieving immortality. I’m sceptical. For now, it’s clear that we are not free from death.

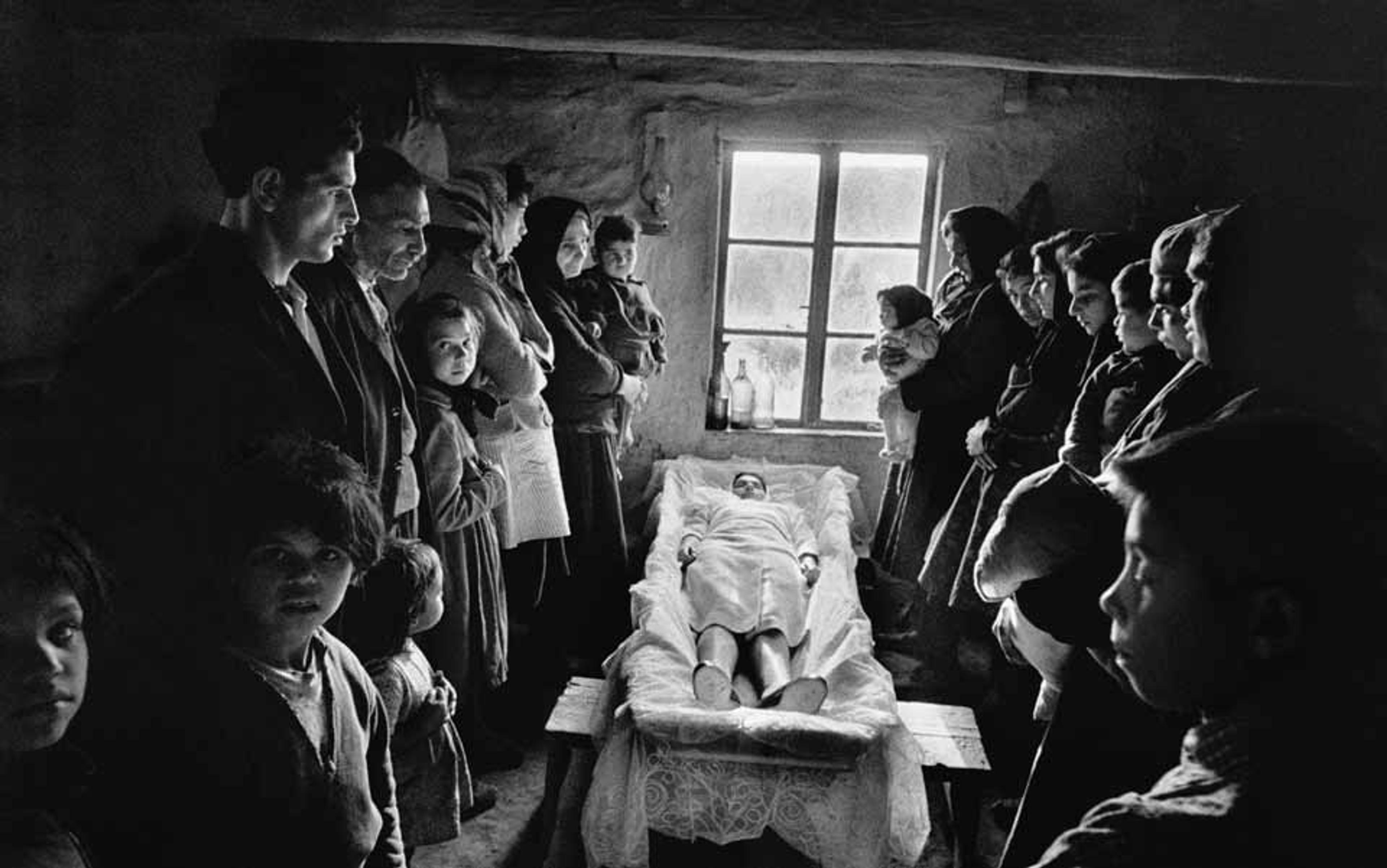

But dying itself has undergone dramatic changes in the past century or so, changes that have given us increasing freedom over death. Today, most people die not of injuries or fast-acting infections but of chronic illnesses such as heart disease and cancer. These chronic illnesses typically bring about a long pre-mortem decline in health. Alongside the availability of new medical interventions and treatments – everything from artificial ventilation to antibiotics to chemotherapy – the comparative slowness of modern death now means we have many more opportunities to shape the timing and circumstances of our deaths.

Our freedom over death will always be imperfect. Nevertheless, the timing and circumstances of our deaths increasingly reflect choices made by patients, their families and their caregivers. They can include the following:

- which treatments to receive for our medical conditions and which not (the cancer patient deciding between surgery and chemotherapy);

- whether to continue to seek cures or extend life, versus opting for palliation or comfort care;

- whether to receive interventions at all (for instance, the heart attack victim with a ‘do not resuscitate’ order); and

- where and with whom death will take place (in a hospital, a hospice, an individual’s home, etc).

In each of these choices, we see attempts to shape death, to delay it or hasten it, to decide when, where, how or in whose presence it will take place. Crucially, these are not choices about whether to die – that’s not within our ambit. They are choices reflecting our growing freedom over death: that is, over its timing and circumstances.

The course of dying belongs less and less to nature or God than to us

Death is, of course, ‘natural’. Medically and biologically, we die because our bodies and brains can no longer sustain the functions requisite for life. We all die of ‘natural’ causes in that sense. But in an era where we have such extensive freedom over death – when it occurs at the end of a prolonged and often highly medicalised process punctuated by choices about when and how dying will occur – it is no longer credible to depict dying as cordoned off from human freedom. A comparison: we now appreciate that ‘natural disaster’ is a misnomer. Natural disasters are unavoidable insofar as they result from the operations of physical systems that we largely cannot control, but exactly how and when they occur (the particular ways in which they prove ‘disastrous’) can be shaped by where, when and how human activities are organised. And just as it is foolhardy to fail to prepare for or to mitigate natural disasters, so too is it foolhardy not to prepare for or mitigate the harms of dying. Fortunately, we now enjoy unprecedented ability to exercise freedom over death to reduce its harms.

Collectively, we are still adapting to this newfound freedom. One sign of our lingering discomfort with this freedom is the belief that assisted dying represents a kind of hubris, a misguided attempt to control or manage death. Some hold that, rather than doctors providing assistance in dying to patients facing particularly gruelling conditions, we should instead let nature (or God, or a person’s illness) ‘take its course’, merely doing our best to ensure that the individual dies without pain and with dignity. As Leon Kass put it: ‘We must care for the dying, not make them dead.’ Assisted dying, from this perspective, foolishly tries to place death itself under human authority.

The trouble with this worry is that we already have a surprisingly large freedom over death, a freedom almost no one opposes on grounds of hubris. The course of dying belongs less and less to nature or God than to us, a fact that those who are not religious objectors, such as Christian Scientists, welcome. There is no social momentum in favour of denying individuals choices regarding life-extending treatments, palliation and the like. If assisted suicide represents a hubristic attempt to usurp nature and replace it with human judgment, then why is it not equally hubristic to try to delay death through medical means, or to hasten it by choosing hospice care, rather than further treatments aimed at extending life? Assisted dying’s opponents draw arbitrary lines concerning which exercises of freedom over death should be permitted.

Therefore, assisted dying cannot be rejected because it amounts to an ‘unnatural’ intervention in human mortality. Rather, it is merely the latest major incarnation of a freedom over death that we have rightfully embraced. We no longer need stand aside and let nature ‘take its course’, and thank goodness for that.

Still, opponents may grant my claim that assisted dying enables us to exercise further freedom over death but wonder whether it is a bridge too far. Do we really need to be legally entitled to medical assistance in dying in order to enjoy sufficient freedom over death?

Many people evidently believe so. Support for the legalisation of assisted dying has been steady for several decades in many nations throughout the world, with about two-thirds of those polled supporting its legalisation. No jurisdiction that has legalised assisted dying has subsequently ended the practice, and public support for the practice tends to grow once legalised. In addition, when assisted dying is not available, many will seek it out at considerable expense or inconvenience to themselves. The Swiss organisation Dignitas has assisted in several thousand deaths for individuals willing to pay significant fees and travel expenses (currently estimated at $20,000), as well as to risk possible legal ramifications in their home countries. There is a high demand for enjoying freedom over one’s death.

Given the lengths to which individuals will go to seek assisted dying, it’s unlikely that any legal or medical regime will succeed in preventing the practice altogether. Realistically, the question we face is not whether assisted dying will take place. The demand for it ensures that it will, and it is likely that we are overlooking the frequency with which assisted dying occurs clandestinely or through the equivalent of a ‘black market’.

Many people thus endorse, through their opinions or their choices, our freedom over death encompassing a right to medical assistance in hastening our deaths. Yet it is not obvious why or how being able to opt for assisted dying is a valuable form of freedom over death. In my estimation, its value becomes apparent when we reflect on the distinctive role that dying plays in human lives.

Socrates’ death strongly reflected his identity and values, whereas the Civil War soldiers’ deaths largely did not

Our freedom over death should include a legal right to assisted dying because sometimes being able to die earlier rather than later not only allows us to avoid suffering but also because of the special role that dying has in our biographies. At the risk of stating the obvious, dying is the last thing we do, and endings matter to us. To see this, contrast two lives – or more precisely, two experiences of dying:

- The Athenian philosopher Socrates was sentenced to die on charges of corrupting the youth and teaching falsehoods about the gods. Though Socrates was given the opportunity to avoid death by going into exile, he nevertheless chose to ingest the fatal hemlock. He went to his death not long after a lengthy philosophical conversation with his friends and students, in which he articulated his beliefs that the soul is immortal and that a virtuous person cannot be harmed by death.

- As Drew Gilpin Faust illustrates in her book This Republic of Suffering (2008), the Civil War confronted Americans with death on an unprecedented scale. Not only were the sheer numbers of soldiers killed in battle staggering, these soldiers died, nearly to the last, in ways at odds with their (and their culture’s) understanding of a ‘good death’. These soldiers typically died frightened and alone, either on the battlefield or in a makeshift military hospital far from their loved ones and, in many cases, with no opportunity to perform the Christian rites of atonement. Some died knowing that they could not expect a proper Christian burial. Many died fighting a war they participated in involuntarily, did not support, or whose causes or significance they could not understand.

Socrates, I submit, had a good death, while many Civil War soldiers did not. The difference consists mainly in how Socrates’ death strongly reflected his identity and values, whereas the soldiers’ deaths largely did not. In Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End (2014), the surgeon Atul Gawande vividly captures the challenge that dying presents to our integrity:

Over the course of our lives, we may encounter unimaginable difficulties. Our concerns and desires may shift. But whatever happens, we want to retain the freedom to shape our lives in ways consistent with our character and loyalties … The battle of being mortal is the battle to maintain the integrity of one’s life – to avoid becoming so diminished or dissipated or subjugated that who you are becomes disconnected from who you were or who you want to be.

Dying is an event in life but, as the final event in life, it has an outsize importance in the integrity of our lives. Dying often represents a monumental challenge to our integrity: how can we make dying something we do, reflecting our values and outlook, as opposed to something that merely happens to us, over which we have little agency? We hope our deaths will reflect us (or the best of us), to reflect the values that define our lives as a whole. When they do not, our deaths end up being alien impositions, jarring final chapters instead of fitting conclusions.

Many of those who opt for assisted dying are, in my estimation, seeking to die with integrity. Survey research finds that the relief of pain or physical suffering often plays a fairly marginal role in their decision. Far more prominent are worries about being unable to participate in worthwhile activities or losing autonomy or dignity. The unifying threads in these worries is integrity, the desire to have one’s final days amount to a chapter in a life that one can recognise as one’s own.

Freedom over death makes it possible for dying to more fully reflect our selves. And a shorter life sometimes is a better reflection of what we care about, and thereby has greater integrity, than a longer life. Being helped to die is sometimes essential to achieving such a life.

I do not mean to convey the impression that deciding to end one’s life prematurely, whether to maintain one’s integrity or for some other reason, is a simple one. It is hard to envision a decision more harrowing than this. But the case for legalised assisted dying does not require that such decisions are simple. In many cases, we should expect some ambivalence regarding the choice to seek assisted dying. We should not expect those who opt for assisted dying to approach death with the serenity of Socrates. The case for legalised assisted dying merely requires that individuals be able to make such choices in the same informed and thoughtful way that they are able to make other life-shaping choices where their integrity is at stake, such as choices regarding marriage, procreation or other medical matters.

After all, it is the dying individual’s integrity that is at stake, and there is every reason to think that they are best situated to judge how to die so as to honour their own values or concerns. Indeed, the freedom to die with integrity is one that many care about even if they decide not to exercise it. As many studies have shown, in jurisdictions where assisted dying occurs by means of self-administration, many individuals who receive prescriptions for the lethal drugs end up not using them to end their lives. Simply having these drugs available can offer peace of mind to those who hope to be able to die with integrity.

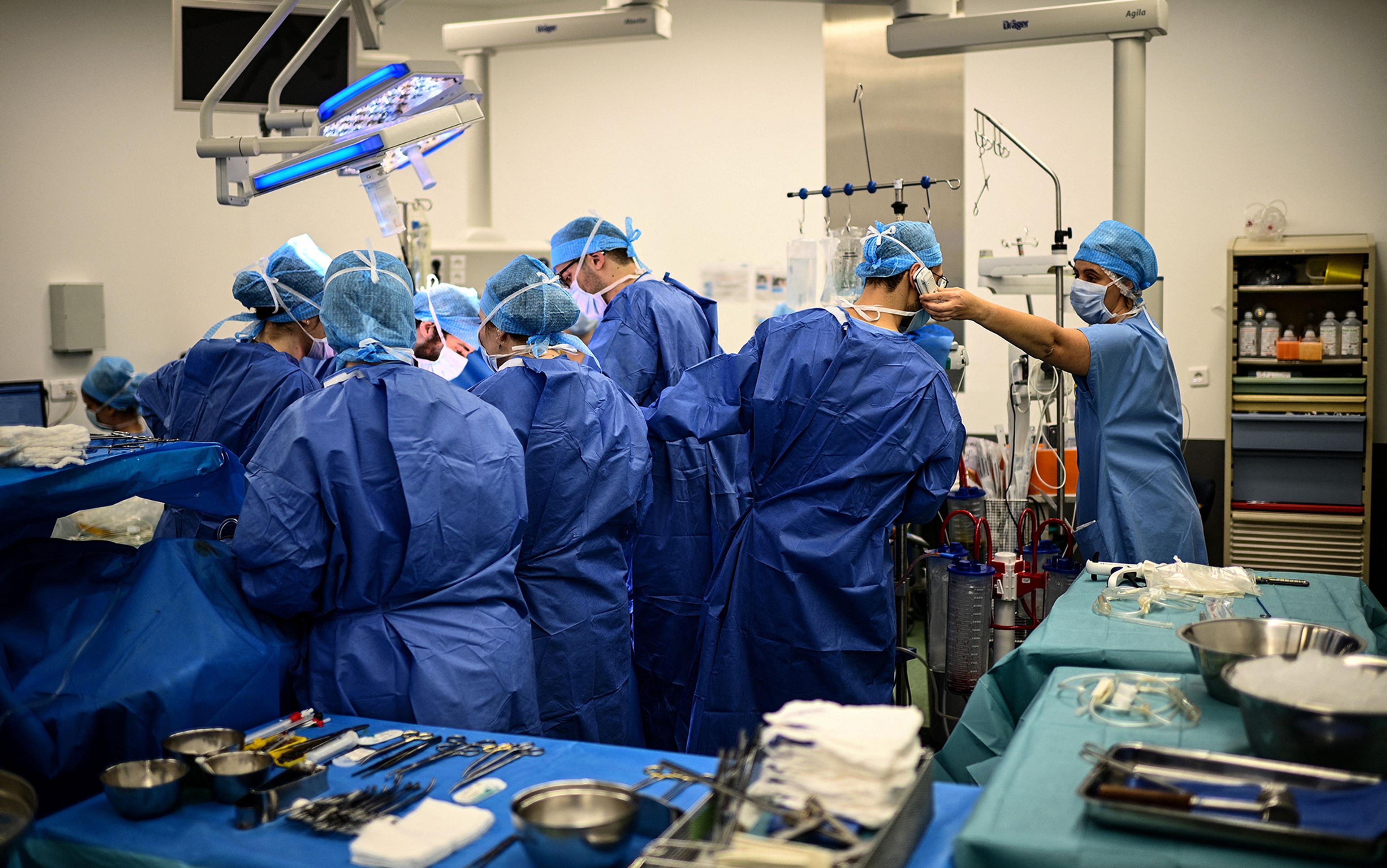

At this point, my opponents may concede that choosing the circumstances or timing of one’s death is a valuable instance of freedom over death but question whether we ought to be able to enlist others’ help in acting on such choices, especially when their help involves ‘active’ measures such as providing us with a lethal medication or even injecting that medication into us. All the more, the topic at hand is medically assisted dying, and doubts may be raised about whether assisted dying is compatible with the values of medicine. Patients do not, after all, have the right to receive from their doctors whatever interventions or procedures they want (patients cannot request medically unproven treatments, or to have medical resources directed toward them in ways that treat others unjustly, for instance).

Opponents of assisted dying may argue that doctors have a clearly defined role – to treat or cure illness or injury – but assisted dying neither treats nor cures the patient’s condition. Furthermore, medicine’s aims do not encompass enabling us to live with integrity. Might there be a right then to choose the circumstances or timing of one’s death but no right that doctors assist one in realising those circumstances or timing?

This line of thought takes a naive view of medicine. Medicine is invariably a value-driven enterprise and, in some cases, doctors forego treating an illness that poses little risk to patients (many cases of prostate cancer, for example) or agree to provide an intervention that benefits a patient despite its not treating an illness or injury (voluntary sterilisation, for example). The treatment of illness or injury thus does not delimit the boundaries of legitimate medical practice, and so the fact that assisted dying does not treat or cure is not a reason to oppose it. Allowing a person’s life to conclude with integrity does fall within the central mission of medicine: to address conditions of the body so as to allow a person to live in ways they see fit.

Doctors are already permitted to contribute to their patients’ deaths in ways that arguably amount to killing

Moreover, individuals concerned about dying with integrity have few if any other options besides the medical profession to provide them with the dying experience they seek. For better or worse, healthcare systems monopolise access to the options we have for exercising freedom over death, including a monopoly on the easeful, non-traumatic, non-violent forms of death most of us want. Medicine’s monopoly on access to these options can be justified on the grounds that lethal medications need to be safeguarded, but this monopoly cannot justify a blanket prohibition on patients having access to such medications when they stand to benefit from them (when, for instance, being assisted to die allows them to die with greater integrity).

That doctors should not knowingly and intentionally contribute to their patient’s deaths is perhaps the oldest argument against assisted dying. But this appeal to ‘do not kill’ faces a dilemma: doctors are already permitted, legally and morally, to intentionally contribute to their patients’ deaths in ways that arguably amount to killing those patients. For example, if anyone besides a doctor removes a person from life-sustaining artificial ventilation, this is standardly classified as killing rather than ‘letting the patient die’. So too then in the case when doctors act with patient consent to remove life-sustaining measures: they kill their patients, albeit justifiably. But if opponents of assisted dying agree (a) that doctors may honour patient requests to accelerate the timing of their death by the removal of such measures and (b) in so doing, doctors are acting to kill their patients, then the argument that assisted dying involves doctors wrongfully ‘killing’ patients falls apart. If doctors may permissibly contribute to killing patients by the removal of life-sustaining measures, then there seems no reason to conclude that they may not contribute to killing their patients (when they competently consent to it and meet other conditions) by providing them with, or administering to them, a lethal medication.

There are of course many other objections to the legalisation of assisted dying. Many of these rest on empirical predictions that are not supported by the evidence that we now have from the jurisdictions where it has been legalised, evidence that now dates back a quarter-century. The availability of assisted dying hasn’t made it harder to access quality palliative care or caused a decline in its quality. Assisted dying hasn’t undermined healthcare for those with disabilities, and those with disabilities generally agree that it is discriminatory and disrespectful toward the disabled to oppose assisted dying in order to protect the disabled. As to worries about ‘abuse’ or ‘coercion’, it is often unclear how to interpret what opponents intend by these terms, but all evidence suggests that abuse or coercion in connection with assisted dying are extremely rare. All the more, for the majority of patients, legalising assisted dying doesn’t erode trust in their doctors and can in fact make possible wider and more candid conversations among patients, doctors and their families about choices at the end of life.

Whenever assisted dying is legalised, its opponents attempt to discredit the law. The most recent example of this is Canada, which passed its assisted dying law in 2016. Advocacy groups depict the law as a catastrophic ‘slippery slope’, but their criticisms do not withstand factual scrutiny: Canadians are not being provided assisted dying due to poverty or homelessness, nor are they turning to assisted dying because they are receiving substandard palliative care for support of their disabilities. (Indeed, it is striking how ‘unmarginalised’, even privileged, beneficiaries of assisted dying tend to be.) Contrary to assisted dying’s opponents, assisted dying laws work as intended, and it is one of the beauties of democratic societies that they can continue to refine their assisted dying laws and practices to ensure fairness and transparency.

So little of our lives is up to us: who our parents are, where we are brought up, how we are educated, even whether we exist at all. To be able to die with integrity offers us a modest opportunity for freedom in an existence whose defining features we are largely not free to choose. Granted, societies may justifiably impose constraints on how we exercise this freedom, constraints aimed at ensuring that we exercise it after due consideration and when it is reasonable for us to want to exercise it. But those in the medical profession ought not suffer adverse consequences when they assist us in exercising this freedom. They ought not be subject to professional sanctions, nor ought they be subjected to imprisonment or other legal penalties. We ought to legalise medically assisted dying and free doctors from such risks.