A great wave of desire for more self-sufficiency is sweeping over the planet. Donald Trump has declared the ‘economic independence’ of the United States and seems to be trying to excise the US from the global trading system his country has so painstakingly built since the Second World War – a system that has delivered considerable economic benefits for nations across the planet.

And the US president is far from alone in wanting to turn his nation inwards and rely less on other countries when it comes to imports of goods and raw materials. China’s president Xi Jinping has, for many years, been advocating zili gengsheng for China, which translates as ‘self-reliance’. In pursuit of this, Beijing has been discouraging imports and trying to enhance Chinese domestic production of everything from food to computer chips.

Others have followed this path too. ‘Russia is a self-sufficient country in every sense of the word,’ boasted Vladimir Putin last year, dismissing the impact of the avalanche of Western trade sanctions that swept over the country in 2022 and sought to turn it into an economic pariah. The Indian prime minister Narendra Modi has adopted a slogan of atmanirbhar bharat, or ‘self-reliant India’, for what is now the most populous nation in the world. Even the traditionally outward-facing European Union has begun exploring how the bloc can achieve greater economic autonomy in areas ranging from energy to defence.

This exaltation of self-sufficiency and the downgrading of the value of trading links amounts to a profound break from the orthodoxy of globalisation – the idea that ever-greater interconnections between nations through trade would enhance the security and prosperity of all. Yet, though it might feel like a very modern departure, this impulse to face inward, and for nations to cast off the shackles of interconnection and dependence, is not new. In fact, it’s ancient.

Over many centuries, it is also an impulse that has been felt as deeply on an individual level as it has on a community level. Indeed, understanding how the two interact and reinforce each other might be crucial to understanding the enduring appeal of this way of thinking – and for getting a sense of where it can lead us, whether as individuals, as nation states or as a global community.

The 4th-century BCE Cynic philosopher Diogenes lived in a barrel in the marketplace in Corinth and was said to bark at people like a dog to demonstrate his scorn for social conventions. When Alexander the Great paid Diogenes a visit, the conqueror of worlds asked the ragged ascetic, who was enjoying a siesta at the time, what he wanted, with the implication being he could ask for anything he liked – property, money, power, status, sex? The answer, so the story goes, was that Diogenes asked him to: ‘Stand a little out of my sun.’

Diogenes speaking to Alexander from the manuscript Les diz moraulx des philosophes, c1418-20. Courtesy the Houghton Library, Harvard University

Whether this encounter between the king and the cynic (from the Greek kynikos or ‘dog-like’) actually happened is questionable. But there’s no doubting the power of the story and the idea it encapsulated. The tale of Diogenes’ extreme indifference to the most powerful ruler in the ancient world has been in circulation for almost 2,000 years as perhaps the supreme example of the desire for self-sufficiency.

Self-sufficiency, or autarky – from the Greek auto (‘self’) and arkeo (‘to suffice’ ) – was seen from the very beginning as a demonstration of personal moral virtue. To be reliant on others was to compromise one’s ability to pursue wisdom. And if self-sufficiency meant sheltering in a barrel, barking like a dog and running the risk of offending a mighty king, then so be it.

But, from those earliest days of Western civilisation, the moral virtue of autarky was not just a goal for an individual, but an aspiration for the collective too. According to Aristotle, a contemporary of Diogenes, the ideal city state in the ancient world was also self-sufficient, and those inside the polity would have everything they needed to pursue a good philosophical life – unlike those outside it.

The ‘scholastic’ argument led to the view that to be more self-sufficient was to be closer to God

‘The term self-sufficient,’ as Aristotle put it, ‘we employ with reference not to oneself alone, living a life of isolation, but also to one’s parents and children and wife, and one’s friends and fellow citizens in general, since man is by nature a political animal.’ This Aristotelian connection between individual and collective self-sufficiency – the personal and the political – endured into the Christian era.

Thomas Aquinas, a powerfully built scholar born in the Kingdom of Sicily in 1225, so underwhelmed his University of Paris classmates that they nicknamed him the ‘dumb ox’. But the dumb ox did more than perhaps any other to build the philosophical underpinnings of the Catholic faith.

Drawing on Aristotle, Aquinas talked of the ‘self-sufficiency’ of God, in the context of the argument that all existence ultimately flowed from the creator, and the deity wasn’t reliant on anything exterior to himself. That was the seminal ‘scholastic’ argument of the medieval age. And it led to the view that to be more self-sufficient was to be closer to God.

But, importantly, Aquinas was an advocate for economic, not just spiritual, autarky. He noted that there are two ways a city can feed itself: by growing food on its own surrounding fields, or through trade. ‘It is quite clear that the first means is better,’ Aquinas concluded in De Regno (1265), his book on kingship. ‘The more dignified a thing is, the more self-sufficient it is, since whatever needs another’s help is by that fact proven to be deficient.’ Aquinas also proffered a moral case for autarky when he noted that ‘greed is awakened in the hearts of the citizens through the pursuit of trade.’

Thus, in the medieval Christian world, the pursuit of autarky – on both a personal and a community level – was sanctified, widening its appeal, and finding a clear manifestation in the monasteries, largely self-sufficient communities independent of external authority, except the Church and God, and producing their own food, wine and clothing.

While arguments for autarky in Europe first arose from appeals to personal morality and character, and functioned as much as spiritual and psychological programmes as they did political ones, elsewhere the links between autarky and nationhood were being more clearly developed.

The policy of sakoku or ‘closed country’ was imposed on the islands of Japan in the 17th century by the Tokugawa shogunate, a form of feudal military dictatorship. Western Christian missionaries were banned and those that were already in the country were persecuted. Emigration was forbidden and foreign trade was reduced almost to nothing. ‘The Christians have come to Japan … to propagate an evil creed and subvert the true doctrine,’ proclaimed an edict from the shogunate in 1614.

Autarky was seen as a necessary means to preserve traditional religion and morality in Japan, but economic isolationism was also bound up with resistance to the incursions of foreign empires and was a practical means of securing sovereignty and control, not just an abstract principle.

For Fichte, commerce among rivalrous European states had served to corrupt relations

As the medieval world gave way to the Enlightenment and Romanticism in Europe, the ideal of autarky was reinvigorated by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. From what he imagined was an anthropological perspective, Rousseau conjectured in his Discourse on Inequality (1754) that primitive man had been naturally ‘solitary’, coming together with others only for mating, and was much happier for it.

Rousseau’s mind’s eye saw an early man:

wandering in the forests without industry, without speech, without a home, without war, and without relationships, with no need for his fellow men, and similarly with no desire to harm them, perhaps even without ever recognising any of them individually, …

There are clear echoes of the freedom of Diogenes here in Rousseau’s vision of a ‘state of nature’. And, importantly, this had implications for his own beliefs about how humans ought to live. Rousseau, like Aquinas before him, made the leap from extolling the general moral virtuousness of self-sufficiency to recommending it as a trade policy for nation states.

‘No one who depends on others, and lacks resources of his own, can ever be free,’ he warned the Corsicans in 1765. ‘[P]ay little attention to foreign countries, give little heed to commerce; but multiply as far as possible your domestic production and consumption of foodstuffs,’ was Rousseau’s advice to the Poles in 1772.

Rousseau inspired one of the paragons of German idealist philosophy, Johann Gottlieb Fichte. In his work The Closed Commercial State (1800), Fichte sought to fuse Rousseau’s proto-anthropological perspective with the ideas of Immanuel Kant, who had envisioned a model of ‘perpetual peace’ among nations.

This represented a significant shift in the concept of autarky, marking its first true incorporation into geopolitical theory. The orthodoxy of Fichte’s time was that trade tended to engender good relations between nations. But for Fichte, on the contrary, commerce among rivalrous European states had served to corrupt relations, and economic life had to be disentangled for peace to have a chance.

‘In a nation which has closed in this way, whose members live only among themselves and very little with foreigners … a higher degree of national honour and a sharply determined national character will develop very quickly,’ claimed Fichte.

Charles Fourier, the son of a cloth merchant from Besançon, took the autarkic ideas of Fichte and Rousseau in a beguiling new direction. Contemporary portraits show an austere-looking individual, with a thin mouth with sharply down-turned corners. Yet Fourier’s rather prim exterior belied one of the most eccentric of the utopian socialists of the early 19th century, with his speculations that the world’s seas would one day turn into lemonade and that humans would evolve tails.

Fourier’s most lasting contribution to the development of the concept of autarky was his vision of an ideal society of self-sufficient rural communities, which he called ‘phalansteries’, a derivation of the words ‘phalanx’ (meaning a military formation) and ‘monastery’. He outlined a ‘unitary education’ for all children in the phalanx, regardless of family wealth, and a ‘social minimum’, which was effectively a guaranteed minimum annual income. The influence of the phalanstery on 1960s hippie commune living is evident. The kibbutzim of Israel also echoed many elements of his ideas.

View of a phalanstery by H Fugèr and Charles-François Daubigny circa the 19th century. Courtesy the Houghton Library, Harvard/Wikipedia

The modern ‘degrowth’ and environmentalist movements also have strong elements of self-sufficient thinking, along with moral implications to reduce our wasteful and destructive ‘wants’, in ways that Diogenes and the early Christians might have approved of.

‘[A] better answer than economic globalisation is a shift in the direction of revitalised, local, diversified and at least partially self-sufficient smaller economies,’ asserted Jerry Mander, an ecologist, in The Case Against the Global Economy (2nd ed, 2001). This was partly because he believed that one of the problems with globalisation was that it encouraged ‘voracious consumerism’. Again, the link between the personal and the social when it comes to autarky rises to the surface.

Mahatma Gandhi’s vision of an India independent of British rule was for a network of ‘tiny gardens of Eden’

Like Fichte before them, today’s Left-wing antiglobalisation activists often argue that free trade disproportionately benefits wealthy nations while harming poorer ones. In this view, autarky becomes the natural path to both domestic and international social justice – an appealing goal for those committed to equity and sustainability. For those same reasons, it has also appealed to those seeking to build a new world, free from European imperial rule.

Back in the 1940s, Mahatma Gandhi’s vision of an India independent of British rule was for a network of economically autonomous villages, ‘tiny gardens of Eden’, growing their own crops and spinning their own cotton for clothing. ‘Every village has to be self-sustained and capable of managing its affairs even to the extent of defending itself against the whole world,’ he wrote. This is why the image of the spinning wheel once sat at the heart of the tricolour Indian flag.

For Gandhi, self-sufficiency did not mean there would be no trade, but rather trade only in the things that the village could not realistically produce itself. ‘Self-sufficiency,’ he stressed, ‘does not mean narrowness. To be self-sufficient is not to be altogether self-contained.’

Yet at other times Gandhi struck a much more isolationist tone, insisting that ‘it is certainly our right and duty to discard everything foreign that is superfluous and even everything foreign that is necessary if we can produce or manufacture it in our country.’ How to reconcile such statements? Gandhi’s self-sufficiency movement – swadeshi in Hindi – has to be understood as self-sufficiency for India primarily in relation to Britain, the imperial overlord. The movement was announced in 1905 in Bengal alongside a boycott of British goods. Swadeshi was Gandhi’s antidote to what he saw as the predatory imperial capitalism of the British. And that mindset of India needing self-sufficiency remained long after independence was achieved.

There was a similar motivation for autarky in post-independence Tanzania, where the president Julius Nyerere’s ujamaa (‘familyhood’ in Swahili) movement in the 1960s and ’70s was founded on the belief that European colonialism and urbanisation had perverted African economic life, and that the answer was a return to self-sufficient, rural living using ‘ox-ploughs’ instead of tractors. ‘Independence means self-reliance,’ stated Nyerere’s 1967 Arusha declaration. For him, autarky and his distinctive vision of African socialism were inseparable.

Progressive thought has long carried a current of economic isolationism. Yet, as recent history makes clear, the drive toward self-sufficiency is by no means confined to the Left or to environmentalist movements.

Take Robert LeFevre, for example – an eccentric figure not unlike Fourier. Born in Idaho in 1911, LeFevre began his career as a self-proclaimed ‘fly-by-night’ door-to-door salesman, and later promoted a New Age cult in the 1930s. But it was only in the 1960s that he found his true calling as a populariser of libertarian economic ideas. At his ‘Freedom School’ in Colorado, LeFevre developed the theory of ‘autarchism’ in an attempt to clarify his philosophy and distinguish his radical anti-government beliefs from ‘anarchism’.

As he put it in the Rampart Journal of Individualist Thought in 1966:

autarchy will signify total self-rule. It will presume a system or social arrangement in which each person assumes full responsibility for himself, proceeds to control himself, exercises authority over himself … and does not in any way seek to impose his will by force upon any other person whatever.

This was essentially a strain of libertarianism reaching back to the ancient Greek ideal of individual self-sufficiency, rather than the political and economic conception.

Modern movements toward economic self-sufficiency have not typically emerged from grassroots efforts

LeFevre was not opposed to trade and was an evangelist for free markets. His school was an implacable opponent of any kind of government intervention or economic redistribution. The future billionaire chemicals and fossil fuels industrial magnate Charles Koch was one of the students of LeFevre’s school in the 1960s and was profoundly influenced by the experience. Koch went on to pour huge amounts of his family’s money into libertarian think tanks, arguing for major tax cuts, drastic reductions in government welfare spending and radical deregulation.

Yet some elements of the modern US libertarian movement do seem, perhaps paradoxically, amenable to the communitarian vision, even if they abhor collectivism. The New Hampshire Free State project, established in 2001, is trying to create a libertarian community in the US, by encouraging like-minded folk to move, en masse, to the state of New Hampshire. ‘By concentrating our efforts in one small state with a pre-existing pro-liberty culture, we are turning the tide against big government, and we’re experiencing the benefits of expanded personal and economic freedoms,’ its website states.

There are estimated to be between 10,000 and 30,000 communes, or ‘intentional communities’, around the world, including religious communities such as monasteries and temples, pursuing personal and spiritual self-sufficiency. But major modern movements toward economic self-sufficiency have not typically emerged from grassroots efforts. Instead, they have often been state-directed. This shift has been largely driven by modern warfare – or, more accurately, the threat of it.

Adolf Hitler’s autarkism was a response to Germany’s experience in the First World War, when the country had been starved by the British navy’s blockade. Writing in the 1920s, Hitler dismissed the idea that Germany could nourish its population through increases in agricultural productivity and lamented that ‘the German people is today even less in a position than in the years of peace to feed itself from its own land and territory’.

The road to national self-preservation for the former lance-corporal would have to run through a radical programme of building national self-sufficiency. And he believed that Germany’s salvation lay in conquering and exploiting the rural bounty of lands to the east, thus gaining the notorious Lebensraum (‘living space’).

In a speech in 1936, when he had ascended to the German Chancellorship and crushed all internal opposition, Hitler made his expansionist territorial intentions plain:

If I had the Ural Mountains with their incalculable store of treasures in raw materials, Siberia with its vast forests, and the Ukraine with its tremendous wheat fields, Germany and the National Socialist leadership, would swim in plenty!

Ironically, Hitler’s nemesis, Joseph Stalin, despite having those fecund lands under his direct control, also felt a dread of national insecurity and decided to pursue a policy of self-sufficiency for the Soviet Union in the 1930s, deliberately cutting off exports and seeking to establish Soviet economic independence from the ‘capitalist world’.

Hitler, Stalin and Mao were primarily motivated by the spectre of war, rather than ideals of national virtue

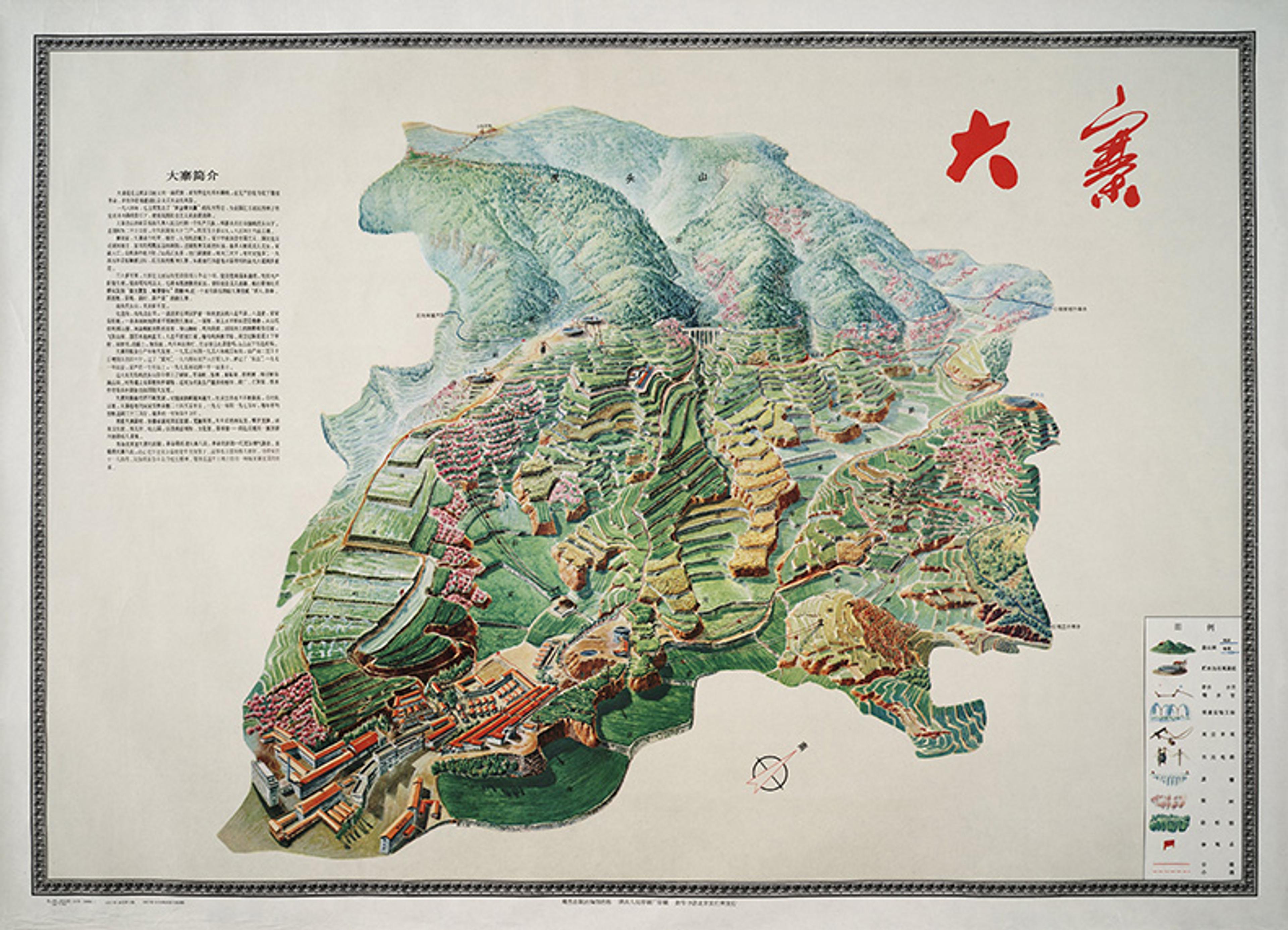

Similar justifications for self-reliance, based on national security, were used in Communist China during Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward of the 1950s, when he sought to create a national domestic steel industry from scratch by compelling farmers to melt down their pots and pans in backyard furnaces. But a personal moral dimension was present there too. The farmers of the hitherto obscure village of Dazhai in Shanxi province were held up by Maoist propaganda as hardworking and self-reliant exemplars to be followed by the entire nation.

Propaganda poster of the model agricultural region of Dazhai in Shanxi province, China, 1977. Courtesy the University of Victoria, Canada

Though the most assiduous modern autarkists lie to the east of China. In the 1950s, Kim Il Sung, the North Korean Communist leader and anti-Japanese guerrilla fighter, made national self-sufficiency not just an important objective, but the lodestar of his new regime. And he called it juche.

‘Establishing juche means … rejecting dependence on others, using one’s own brains, believing in one’s own strength, displaying the revolutionary spirit of self-reliance,’ Kim explained. Squint and it’s possible to see a relationship between that and the aspiration to personal independence embodied in autarky in ancient Greece.

In reality, however, figures like Kim, Hitler, Stalin and Mao were primarily motivated by the spectre of war, rather than ideals of national virtue, when they implemented their programmes of national isolationism. The outcomes of their visions for self-sufficiency were catastrophic, resulting in genocide and suffering on a scarcely imaginable scale. Today, North Korea remains a hermit kingdom, shaped by a totalitarian family cult, effectively a prison state for its people, a warning of the economic and social toll of isolationism.

Yet despite the economic disasters the pursuit of autarky has often wrought, it’s important to recognise that its allure has been felt by some outstanding national economic success stories too.

In January 1790, George Washington, the first president of the United States, rose to deliver his first message to the US Congress: ‘A free people ought not only to be armed, but disciplined,’ he declared, ‘and their safety and interest require that they should promote such manufactories as tend to render them independent of others for essential, particularly military, supplies.’

The context was the threat of Great Britain, which had been cast out in the War of Independence but which was still a profound military danger to the nascent republic. And Britain was a free-trading, industrialising superpower. Washington and his treasury secretary Alexander Hamilton believed they had to build up the States’ industrial base to enable the republic to defend itself. And this meant a high wall of import taxes – tariffs – to prevent the ‘infant’ factories of the US from being suffocated by cheaper imported products from a more productive Britain. One of the first acts of the first Congress was the imposition of a tariff.

It’s striking to compare Washington’s first address to Congress with what Trump said to the same institution

The ‘American System’, as it became known, inspired a German émigré to Pennsylvania called Friedrich List to write an influential book in 1841 recommending what he called a ‘national system of political economy’, which rejected the canonical arguments of the likes of Adam Smith and David Ricardo on the rationality of nations pursuing free trade. Instead, List said that countries with great unrealised industrial potential that were trying to catch up with the productivity frontier leader – in this case, Britain – should act to protect their immature factories from competition with the leader with powerful import restrictions until they were strong enough to compete. It remains a compelling argument today for leaders of both developing and wealthy nations alike, often invoked to justify trade protectionism as a cornerstone of industrialisation or re-industrialisation strategies.

It’s rather striking to compare Washington’s first address to Congress with what Trump said to the same institution in 2025. ‘If we don’t have … steel and lots of other things, we don’t have a military and, frankly, we just won’t have a country very long,’ asserted the 47th president, explaining why he had recently re-imposed tariffs on steel imports. ‘We used to make so many ships. We don’t make them anymore very much, but we’re going to make them very fast, very soon.’ By explicitly linking trade policy to national self-reliance and defence capabilities, Trump was resurrecting ideas that were influential at the very birth of the US republic.

Others today are tapping into similar historical currents. Mencius Moldbug, the blogging alias of the US computer scientist Curtis Yarvin, is a prominent tech-authoritarian theorist whose influence extends to some Trump-aligned politicians and wealthy backers. Yarvin advocates dismantling US democracy in favour of a monarchy or a national ‘CEO’-like figure.

As international travel collapsed at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Yarvin saw his moment, not just tolerating isolationism ‘but promoting it’. ‘This state of absolute isolation is not generally ideal. But if we need one relationship that clearly combines unconditional independence with unconditional peace, absolute isolation is always available,’ he wrote online. ‘Any country, at any time, can or should be free and able to isolate itself completely from the world.’

This, he said, in an echo of Fichte, would enhance the prospects of peace between states. And Yarvin drew on some historic Asian autarkic regimes for justification:

Had the Western powers honoured the wishes of the Qing Dynasty and Tokugawa shogunate and not only complied with these policies, but cooperated in enforcing isolation against their own citizens, the historical treasures – human and physical – of these ancient civilisations would still exist. What internationalist can stand up and call it good that we destroyed these societies?

Yarvin’s policy recommendation for 21st-century America? ‘Neo-sakoku’. The autarkic urge makes for some strange bedfellows.

Some anthropologists argue that economic trade between groups of humans likely extends back hundreds of thousands of years. In Kenya’s Olorgesailie basin they have found hand-worked axes made of obsidian, a naturally occurring volcanic glass. The obsidian is not from the area, suggesting that these Stone Age humans who lived some 320,000 years ago were trading with other groups. Part of what defines our species – making us distinct from other apes – seems to be Homo sapiens’ co-operative and social nature and, specifically, our capability for ‘cultural learning’. Rousseau was mistaken to believe that primitive man was a self-sufficient loner.

And the evidence is unambiguous that globalisation – greater trading links, the transmission of know-how and technology, more cross-border investment, the migration of people – has delivered spectacular material benefits for humankind and higher living standards over recent centuries, and especially in the era since the Second World War. There have, undoubtedly, been some communities who have been disrupted and suffered due to the impact of globalisation, but there’s no reason to believe, despite what some politicians argue, that a mass turn inwards by nations would undo that damage. And such a retreat would likely cause severe harm to the livelihoods of billions of others across the planet. Trade and interconnection, whether or not we realise it or like it, is part of who we are – and always has been.

Yet it’s futile to deny that the impulse to self-sufficiency – to economic unsociability – also reaches very deep into our psyches and our history. What’s most striking about autarky is its adaptability as a programme and an ideology. It can appeal impressively across seemingly opposing political, social and ideological lines. It’s been adopted, at various times, by political movements on the Left and the Right, by believers and atheists, by nationalists and cosmopolitans, by fascists and communists, by rich states and poor states, by imperial powers and the colonised, by environmentalists and industrialists. It can be justified by the objective of peace or the demands of war. Any unit – from the individual, to the household, to the village, to the city, to the nation – can apparently aspire to self-sufficiency. It can be borne of a backward-looking nostalgia – a desire to turn the clock back or preserve the status quo – or of a belief that it’s a progressive and necessary programme to build the future. Like a historical El Niño weather pattern, the drive for self-sufficiency keeps returning, unpredictably but, also, seemingly inevitably.

So what makes the autarkic urge so persistent? That protean ability to be moulded and affixed to a seemingly endless host of ideologies is surely key. But perhaps it’s also that umbilical link in autarky – evident since the days of ancient Greece – between personal morality and the question of how we should relate to each other within communities and between communities. To be successful, political movements have to appeal to something fundamental in everyone’s nature. Our innate sense of the virtue of self-reliance is often the foundation stone on which they build.