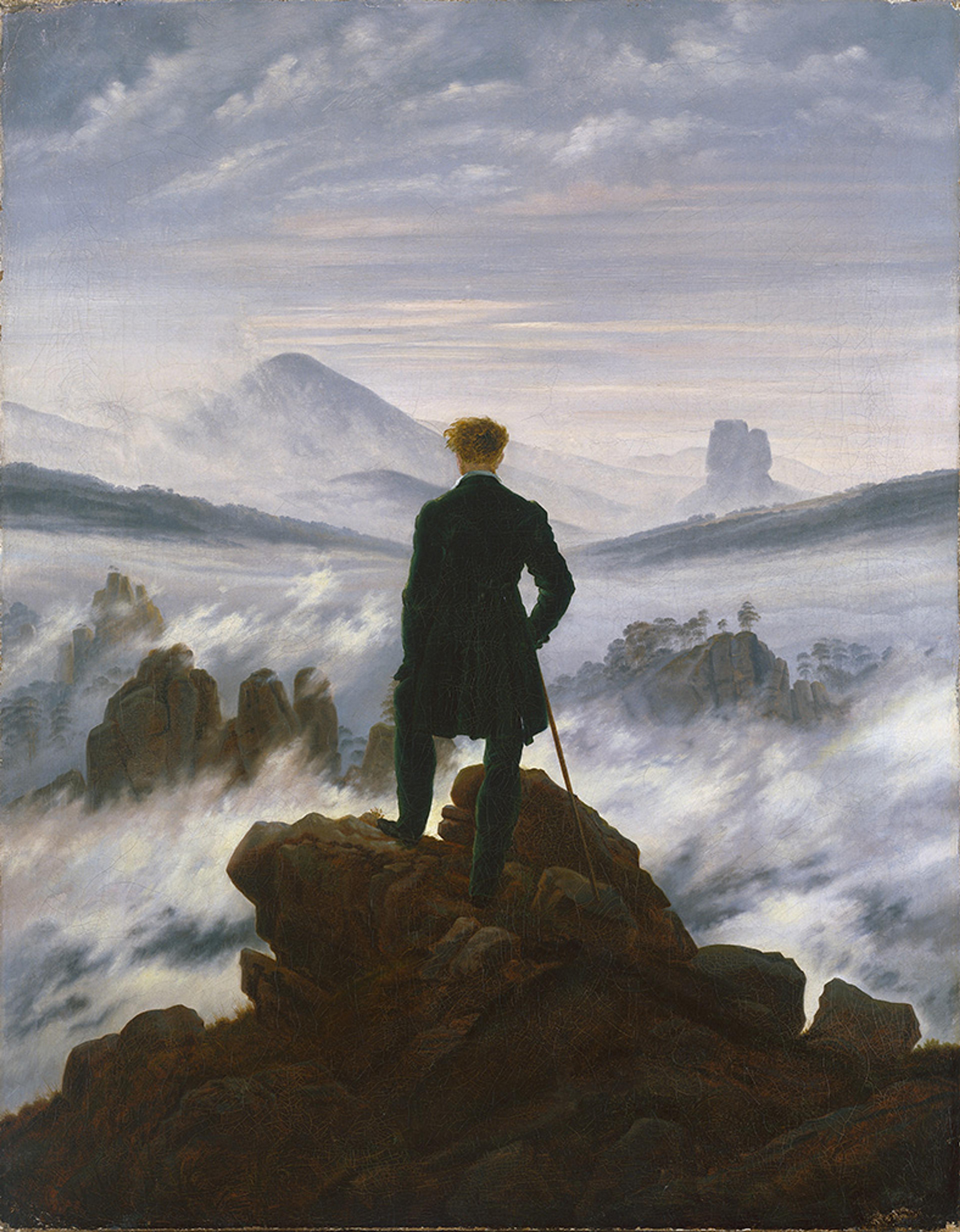

On 5 September 1774, in a small town overlooking the Baltic Sea, a Lutheran candle-maker and his wife welcomed their sixth child into the world. The boy, named Caspar David Friedrich, would grow up tall, introverted and solitary in an age that had not yet invented the myth of the lonely genius. Today, he is considered the greatest of Germany’s Romantic artists. His painting, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (c1817), in which a lone man stands on the peak of a mountain, looking towards a distant fog-shrouded horizon, has come to define how we understand the philosophical and artistic movement known as Romanticism.

But Friedrich wasn’t always remembered this way. For much of the 20th century, few knew his name. Those who did mostly associated his work with the emergence of German nationalism in the 19th century – a cultural humus that fed into the Nazi conception of Vaterland (the ‘fatherland’). Adolf Hitler loved and imitated Friedrich’s work and, through gross misappropriation, eventually turned the painter into a national icon of Nazi Germany. This lent the painter’s work an aura of suspicion in the postwar era, and he struggled to find a respectable place in the history of art.

A lot has changed in the past 50 years: Friedrich is now rightly appreciated for ushering in an artistic and intellectual breakthrough in modern art. For many, this breakthrough is associated with that one iconic painting, an image so deeply embedded in our cultural landscape that we may no longer see it as art. Like Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, or Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers, Friedrich’s Wanderer is everywhere: tote bags, T-shirts, TV shows, billboards, book covers, Instagram posts, advertisements, videogame artwork and internet memes. The painting – which has been held at the Hamburger Kunsthalle since 1970 – is now used to epitomise everything we know (or we think we know) about historical Romanticism: raw experience, the sense of longing, the search for freedom, the sublimity and mystery of the natural world.

The Legend of Zelda for Nintendo Switch. Courtesy Nintendo

But there is something wrong with this association. Our modern admiration of the Wanderer has led to a distorted understanding of both Friedrich and the movement he came to represent. In the process of rediscovering this once-overlooked artist, we have forgotten the original power of his work. We have also neglected his other works, some of which are now considered far superior to the Wanderer – especially as representations of that original power. In fact, according to the German art historian Jens Christian Jensen, Friedrich’s most famous painting must ‘be viewed as an artistic failure’.

Through this ‘failed’ work, we have come to celebrate a strange, simplified and flattened version of Romanticism. In many ways, the Wanderer represents our age, more than Friedrich’s.

This is the story of why we chose the wrong painting.

Friedrich was born in Greifswald, a town in the province of Pomerania, during a period of profound social and cultural transformation in Europe. In the decade he was born, the 1770s, a mix of aristocratic privilege and laissez-faire economics were driving artisans and farmers deeper into poverty and dissatisfaction, foreshadowing the revolutionary waves that would sweep the continent in the following century. Cultural sensibilities in countries like France and England were also shifting, with more sentimental forms of art beginning to challenge the dominance of rational aesthetics.

But these broader conditions had not deeply penetrated the remote region of Pomerania in the late 18th century. As a result, Friedrich’s worldview, so central to his art, was shaped by other influences as he grew up. The first was God. Raised by a strict Lutheran father, Friedrich remained a devout Christian all his life. The second was the natural world. When he was 13, his younger brother drowned as the two boys were ice-skating on a frozen lake, and the incident seems to have deeply impacted Friedrich. These two elements – a remote, even elusive God, and a sublime-yet-menacing nature – would become the trademarks of his art in the years to come.

As an aspiring artist, Friedrich studied landscape painting in Copenhagen, then in 1798 moved to Dresden, the ‘Florence of the North’. He was slow, careful and meticulous in everything he did. During an age when many people in Europe didn’t live past their mid-40s, Friedrich began working on oil paintings only in his early 30s. His first significant work in this new medium was a commission: an altarpiece for a private chapel.

The Jena Circle dreamed of a world that would one day become our own, inventing new ideas of freedom

When he finally decided to show this work to the public, in 1808, it caused turmoil almost immediately. As its title suggests, Cross in the Mountains (1808) depicts a tall, slender crucifix on a mountain peak. We see the cross from an elevated position, as a bird rising up in flight might view it. There is no real perspective, no vanishing lines. The mountain, more than the cross, is the real subject of the composition. At the time, one outraged local critic, Friedrich Wilhelm Basilius von Ramdohr, expressed the novelty of the painting when he wrote that it was as if ‘landscape painting were to sneak into the church and creep onto the altar’. The landscape wasn’t just the background against which the cross stood, or a stage on which God could manifest. The landscape was God. This was unprecedented in European painting, and abhorrent to those still deeply rooted to the traditional idea that art should imitate classical works – an influential approach promoted by the German art historian and archaeologist Johann Joachim Winckelmann in his book The History of Art in Antiquity (1764). Through Friedrich’s Cross, a novel cultural sensibility found full artistic expression, even if the artist was not fully aware of his innovation. A new era was dawning. But its origins didn’t lie only with Friedrich.

Cross in the Mountains (1808) by Caspar David Friedrich. Courtesy the State Art Collection, Dresden

During the last decade of the 18th century, around the time that Friedrich was experimenting with landscapes, one of the most sweeping intellectual adventures in the history of ideas was unfolding a mere 100 miles to the west of Dresden, in the university town of Jena. This adventure was inaugurated by a group of friends that included the writer J W Goethe, the philosophers Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Friedrich Schelling, the poet Friedrich von Hardenberg (known as Novalis), and occasionally others, including the naturalist Alexander von Humboldt and his brother, the philosopher Wilhelm von Humboldt. This group, later known as the ‘Jena Circle’, first gathered around the home of the playwright Friedrich Schiller, and then later at the home of August Wilhelm Schlegel, a scholar who specialised in studies of India, and his wife Caroline Schlegel, an intellectual and writer. Influenced by the events of the French Revolution, the members of the Jena Circle dreamed of a world that would one day become our own, inventing new ideas of freedom, self and nature, authenticity and irony. They were also the first to think of the individual genius as necessarily opposed to an oppressive society.

It was in this extraordinary milieu that the literary critic Friedrich Schlegel, August Wilhelm’s brother, used the term romantisch (‘romantic’) with a new and modern meaning. Previously, from as early as the 17th century, ‘romance’ had been used as a pejorative term connected with anything that was ‘fanciful, bizarre, exaggerated, chimerical’, according to the 20th-century English author J A Cuddon. This definition slowly began to change through the work of the Jena Circle. But what really accelerated its spread was the publication of a controversial book that popularised the Circle’s ideas: On Germany (1810) by the French writer Anne Louise Germaine de Staël.

Madame de Staël, as she is commonly known, was an important and complicated figure in France. She was the daughter of Jacques Necker, the finance minister of King Louis XVI during the tumultuous events of 1789, when the French Revolution was beginning. More than a decade before the publication of On Germany, she had hosted an influential cultural salon in Paris, but her moderate political positions earned her two periods of exile: first self-imposed during the Reign of Terror, beginning in 1793, and later during the early years of Napoleon’s rule, beginning in 1803. It was during this latter period that she visited Germany, met Schlegel, and became acquainted with the ideas of the Jena Circle.

Romanticism was becoming a synonym for modernity: everyone wanted to be a Romantic

‘The word romantic has been lately introduced in Germany,’ writes de Staël in On Germany. She presents German Romanticism as a new, modern sensibility distinct from the ‘ancient’ Greek and Roman classicism that dominated French culture in the last decades of the 18th century. For de Staël, only Romanticism was capable of leading France toward ‘further improvement’. Romantic literature and poetry weren’t merely imitations of someone else’s history. They could be ‘rooted in our own soil’, which would allow them to ‘acquire fresh life’. This wasn’t only about aesthetics. It was a political message disguised in the form of literary analysis: de Staël was suggesting that the French imperialistic ambitions at the time were based on an outdated cultural paradigm (ie, classical antiquity).

On Germany was published at a moment when Napoleon’s influence was waning and many intellectuals in Europe were seeking new forms of art and philosophy. De Staël’s response, borrowed from the Jena Circle, involved turning inward, drawing on passionate emotions and experience rather than aligning with the artistic and philosophical ideas of the distant past. It involved embracing a kind of modern poetry that, in de Staël’s words, ‘calls forth our tears’.

The influence of On Germany was immense. The book became a bestseller, even after all 10,000 copies of the first edition were destroyed by Napoleon, who was quick to declare it anti-French. When it was reprinted in London in 1813, after being censored in France, the book spread across the continent, giving readers in Europe a framework to understand the changing sensibility of the post-revolutionary years.

And so, by 1815, Schlegel’s new understanding of the word ‘romantic’ was in use in Russia, Italy, Spain and England. Romanticism was becoming a synonym for modernity: everyone wanted to be a Romantic.

In many ways, Friedrich’s work followed the wider twists and turns of the Romantics, even though he had little contact with the Jena Circle – so little, in fact, that it’s doubtful whether he was aware of the impact they were having on German culture. In Dresden, Friedrich led the life of an ascetic: he lived and worked in a small studio by the river Elbe, so bare of any comfort that a visitor in 1813 compared it to the ‘eviscerated corpse of a dead prince’. Outside his monastic cell, contact with the art world was minimal. For whatever reason, he did not form strong friendships with his few acquaintances in that milieu. Although he maintained a long correspondence with the painter Philipp Otto Runge, there are reasons to believe that the two never became close friends. For Friedrich, inspiration always came from within, and never from without – a quirk that would become a quintessential Romantic quality of lone creative geniuses. And yet, somehow, the private world of the ascetic artist remained mysteriously attuned to the larger cultural sensibility in Germany.

In the same year that de Staël’s book was published, Friedrich exhibited a new painting, Monk by the Sea (1810), at the Academy of Arts in Berlin. If the Cross introduced the public to his mystical view of nature, the Monk was a step into a completely unknown territory. The monk of the title is a tiny figure in the bottom left corner. Four-fifths of the canvas contain only sea and sky, and they merge in a way that will later be echoed in the abstractions of J M W Turner and Mark Rothko – a connection made by the American art historian Robert Rosenblum in 1961, who suggested that the Monk represents one beginning for modern abstract art. However, to an early 19th-century viewer, this field of colour appeared as a near-total emptiness. The German poet and dramatist Heinrich von Kleist, who attended the exhibition in Berlin, wrote that: ‘The picture, with its two or three mysterious objects, lies before one like the Apocalypse.’ He then concluded: ‘since, in its uniformity and boundlessness, it has no foreground but the frame, the viewer feels as though his eyelids had been cut off.’

Monk by the Sea (1810) by Caspar David Friedrich. Courtesy the National Gallery, Berlin

These vivid, even violent words, so typical of Kleist’s incendiary prose, give us an idea of the novelty of Friedrich’s Monk. Kleist emphasised the lack of perspective in Friedrich’s painting, drawing attention to the absence of a real foreground and, thus, the absence of a background, too. Such an absence was why conservative critics had earlier revolted against the sacrilege of the Cross: there was almost nothing in the picture except for nature. With the Monk, Friedrich had pushed this idea toward its limit. As Kleist had correctly realised, a painting like the Monk was a threshold: one step forward, and you plunge into the abyss. From this point on, Friedrich could only go back.

In the years that followed, de Staël’s On Germany distributed the Jena Circle’s Romantic ideas to Europe’s bourgeoisie – the class that emerged victorious from the French Revolution. These ideas became enormously successful, but this was also the seed of their eventual corruption: the birth of a diluted, digestible version of Romanticism. This is the version that is most well known today.

Early Romanticism was an extreme philosophy. It was predicated on an almost fanatical adherence to one’s own values, a loyalty to one’s own private world, which often proved fatal to its proponents. Many of the early Romantics died young or displayed an inclination for self-destruction that had been unseen in similar cultural movements in Europe. And those who didn’t die tended to live difficult lives. Even love, the early Romantics thought, must be painful to be real.

To Romanticise the world, distant horizons must remain forever distant, desires forever unsatisfied

Consider Novalis’s storied relationship with Sophie von Kühn, who became engaged to the poet the day she turned 13, in 1795. Two years later, she died from tuberculosis, which would become the Romantic illness par excellence – it would eventually kill Novalis, too, just four years later. A few painful months after his fiancée’s death, Novalis wrote the following in his diary:

The lover must feel this gap eternally and keep the wound open always. God grant me to feel eternally this indescribable pain of love – the melancholic remembrance – this courageous longing – the manly resolution and the firm and fast belief. Without my Sophie I am absolutely nothing – With her, everything.

To Romanticise the world, distant horizons must remain forever distant, desires forever unsatisfied. Death at a young age wasn’t just an accident or the consequence of lives lived fast and hard, but an essential part of the Romantic project: John Keats and J W Polidori died at 25, Novalis at 28, Percy Bysshe Shelley at 29, Kleist at 34, Lord Byron at 36. What could be a better way of never meeting the distant horizons of your hopes than dying before you reached them? It’s not chance, then, that those who didn’t die young strayed into madness, poverty, bigotry or irrelevance. Early Romanticism was a passionate philosophy of youth: it had no place for the tranquillity of middle age.

Romanticism would have never reached the European masses and penetrated so deeply into the cultural texture of our society if it had retained its original form. It would have been hard, if not impossible, to convert millions to a worldview that considered suffering as an essential corollary of an intensely lived life. Strong passions and unhappy loves worked perfectly in novels – a genre that took on its modern form around the same time that Romanticism was being developed – but daily life was another matter. De Staël’s On Germany gave readers the cultural tools to make Romanticism liveable. But by that time, the mid-1810s, the artistic and philosophical excitement of the Jena Circle was over and many of its members were either dead, disgraced or had been pushed to the margins of Germany’s intellectual landscape.

On Germany produced a palatable, idealised version of the recent past. But de Staël’s version of this history wasn’t the only reason why the sharpness of Romanticism was dulled as it spread. The fires of the French Revolution, which created the conditions for Romanticism, were now smouldering ashes: across Europe, society had already begun to transform again.

A parallel change was taking place in Friedrich’s life around the time he painted the Wanderer around 1817. Once again, the success of On Germany played a role, albeit indirectly.

When Friedrich exhibited the Cross, in 1808, it shocked art critics who were mostly incapable of understanding what they were seeing. As ideas about Romanticism spread, critics realised that Friedrich’s work was an outstanding example of ‘Romantic art’ – that is, modernity in the form of an oil painting. This newfound appreciation for Romanticism had a practical effect on Friedrich’s life, who in 1816 became a member of the Saxon Academy of Arts in Dresden, a position that gave him a stronger reputation in the art world and newfound financial stability.

And so, the isolated reality that once defined the artist-monk began to change. In the same year the Wanderer was completed, the 43-year-old Friedrich married Caroline Bommer, a woman nearly 20 years his junior. The couple would go on to have four children, three of which survived into adulthood. They moved from his studio on the Elbe to a slightly larger one just a few doors down on the same road. Friedrich was now a well-known and respected painter, a husband, a father.

We can see the signs of an artist who has decided to put aside experimentation and seek comfort in tradition

His tranquil maturity, his quiet happiness, can be seen in paintings from this period, which often feature a lighter colour palette, a more hopeful atmosphere and, significantly, women. Friedrich also started to become more involved in the political concerns of his day. During the last part of the Napoleonic wars, his sympathies progressively moved towards the nationalism that was taking root in Germany. And so, political symbols, such as soldiers and bleeding oaks, started appearing in his paintings. Friedrich’s nationalism was a quintessentially Romantic impulse, relatively common during his age. For a short moment, he was everything that the people around him expected him to be.

We can see all this in the Wanderer: tranquillity, nationalism, self-assurance and artistic maturity. We can also see the early signs of an artist who has decided to put aside experimentation and seek comfort in tradition. The absence of perspective in earlier paintings had once caused scandal. In the Wanderer, perspective was solidly re-established: foreground and background are clearly distinguishable. There is no longer an ‘apocalypse’ happening, in Kleistian terms. The human figure, which was once so small and marginal, and almost invisible in the Monk, reclaimed its place at the centre of the picture. The Romantic tropes of distant horizons, lone figures, sublime nature and fog are all used in a way that maximises their impact: they are now legible, written in a language that the viewer can understand and relate to. This overemphasis is part of the reason why the critic Jensen would later describe the painting as ‘an artistic failure’. The exaggerated human ‘wanderer’ creates a figure who is not sinking into the environment but set outside it.

From an artistic point of view, the Wanderer is a reactionary painting: eight years after reaching the threshold of the apocalypse, Friedrich restored order to give the public a more reassuring, relatable and ultimately conservative version of Romantic art. If this is the version that survived to the present, it’s because the idea of Romanticism itself was going through a similar transformation in the 19th century.

By the time Friedrich painted the Wanderer, Napoleon had been defeated and absolute monarchies were being restored throughout Europe. In this new political landscape, a major force was beginning to silently reshape the lives of millions of people. And within a few short decades, ‘dark satanic mills’ as the poet William Blake called them in 1808, would spread across the continent. As industrial capitalism arrived, and revolution was unevenly replaced by restoration, a new actor was rising in European economies: the bourgeois middle-class consumer.

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (c1817) by Caspar David Friedrich. Courtesy Hamburg Art Museum/Wikipedia

Rather than being hostile to this change, the transformed ideas of the Jena Circle allowed it to flourish. This may sound contradictory. How could Romanticism, an intellectual revolution built on independence, nonconformity and rebellion, foster a world of consumption?

The answer lies with the unique Romantic understanding of experience. ‘Romanticism tells us that in order to make the most of our human potential we must have as many different experiences as we can,’ writes Yuval Noah Harari in Sapiens (2011). ‘We must open ourselves to a wide spectrum of emotions; we must sample various kinds of relationships; we must try different cuisines; we must learn to appreciate different styles of music.’ Today, we take it for granted that experience is the essential matter of a richly lived life, but in the 18th century, before the Jena Circle emerged, this was a radical and potentially dangerous claim.

As new products became available, the early Romantics were teaching people to consume experiences

Consider the English writer Samuel Richardson’s novel Pamela; or Virtue Rewarded (1740). What made this sentimental book an international bestseller, and possibly the first novel in the modern sense, was that its readers could experience life through the eyes of its protagonist. They could feel her feelings and suffer as she suffered. At the time, the reality of such proxy experiences seemed safely contained within the realm of fiction. But then readers of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) supposedly started killing themselves. Experiencing the world through Werther’s eyes felt so real that his fictional pain seemed to overflow into reality. Just a few years later, Schiller’s dramatic play The Robbers (1781) appeared to justify violence in the name of freedom – an idea soon to be realised on a massive scale during the years of the French Revolution. By the time the early Romantics started gathering in Jena, there was a deep hunger in Europe for both experience and freedom. These linked concepts produced a nameless feeling that would soon be called ‘Romanticism’.

And what about consumerism? Until the 19th century, it played only a minor part in the European economy. The consumable luxuries of the previous century simply weren’t available to everyone. However, increases in production and importation soon brought new goods – cotton, tea, sugar and other consumables – to a growing middle class. It’s during this tremendous moment of change that Romanticism (or at least the version of the movement that was absorbed by Europe’s new middle classes) played a crucial role in allowing consumerism to penetrate more deeply into the fabric of society. The early Romantics had already taught people how to consume. What the Jena Circle hungered for were not goods but experiences. This included experiences of nature, God, love, or even psychoactive substances. Experiences, the very fabric of the Romantic world, could now be bought and sold.

This version of Romanticism permeates our lives today. Think about love. Romantic love wouldn’t be the industry that it is if it wasn’t popularised during the first half of the 19th century when Romantic literature reached larger middle-class audiences, spilling over into reality to foster a seemingly inexhaustible market of love tokens and Valentine Day’s cards. When Erich Fromm argues, in The Art of Loving (1956), that romantic love has become indistinguishable from consumerism, he is merely noticing the culmination of a process more than a century in the making.

In Andrea Wulf’s chronicle of the birth of Romanticism, Magnificent Rebels (2022), she explains how the Jena Circle influenced the world we have inherited. ‘We still think with the minds of these visionary thinkers, see with their imaginations and feel with their emotions,’ she writes. ‘We might not know it, but their way of understanding the world still frames our lives and being.’ According to Isaiah Berlin, Romanticism represents ‘the greatest single shift in the consciousness of the West that has occurred.’ So how does the Wanderer fit into this story of Romantic consumption?

By the early 1820s, the German public was tired of Friedrich’s brand of mysticism. Traditional forms of religious painting were now better regarded in Germany. Elsewhere, Romantic art survived, but it often acquired explicitly nationalistic meanings, as in Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830) or Francesco Hayez’s The Kiss (1859). Friedrich’s honeymoon period with Caroline didn’t last long either: a few years after their marriage, he became obsessed with fantasies of her unfaithfulness, retreating more and more into himself, growing more misanthropic, suspicious and solitary. In 1835, aged 61, he suffered a major stroke that progressively left him unable to paint. Five years later, he died.

Liberty Leading the People (1813) by Eugène Delacroix. Courtesy the Louvre, Paris

The Kiss (1859) by Francesco Hayez. Courtesy the Brera Art Gallery

For a long time, this was the end of Caspar David Friedrich. For decades, he was mostly forgotten, a representative of an artistic school irremediably out of fashion. Then, at the turn of the 20th century, he was rediscovered by the Expressionists and the Surrealists, who gave a new, unconscious meaning to his eerie landscapes devoid of human presence. Existentialism also played a part: few painters gave better representation of the human search for meaning than Friedrich’s lonely figures lost in the inscrutability of the natural world. This recovery might have granted him a safe legacy in the history of art, but his paintings soon fell into other hands. Hitler loved Friedrich’s work so much he turned him into a national icon under Nazi Germany, celebrating his heroic lone figures, all-German landscapes and the nationalism that marked the last decades of his life. This is why Friedrich’s work was looked at with suspicion after the Second World War: many remembered that Hitler considered the Romantics ‘the most glorious representatives of those noble Germans in search of the true intrinsic virtues of our people,’ and that the centenary of Friedrich’s death had been celebrated in full regalia by the Reich in Dresden in 1940.

In time, the painting became an icon of human introspection, individual striving and the sublime

Rediscovered in the late 1950s, Friedrich’s work seemed to finally have a chance of being appreciated without prejudices and biases. In 1959, the Tate in London exhibited 14 of Friedrich’s paintings as part of a large exhibition of Romantic art. This rekindled interest reached new heights in 1972 with a second exhibition at the Tate that focused exclusively on Friedrich and would, according to the catalogue, ‘for the first time provide a comprehensive account of this great artist’s achievement.’ In the 1970s, major exhibitions in Dresden and Hamburg drew further attention to Friedrich’s work. But that newfound focus took shape around a single painting – one that wasn’t even included in the 1972 Tate exhibition.

Unlike any of his other paintings, Friedrich’s Wanderer flourished under the conditions of the late 20th century. Perhaps it aligned with the rise of environmental consciousness and New Age thought in the 1970s; perhaps it was propelled through the increasing availability of art prints, which made affordable reproductions accessible. In time, the painting became an icon of human introspection, individual striving and the sublime.

But what does the Wanderer really teach us? Is it a window that grants us an unobstructed view of German Romanticism’s revolutionary potential? Or is it a mirror that endlessly and obsessively reflects a safe, conservative image of ourselves?

In 1888, Eleanor Marx – the youngest daughter of Karl – and her partner Edward Aveling wrote that her father used to say the following about the Romantics (specifically the English poets Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley):

The true difference between Byron and Shelley consists in this, that those who understand and love them consider it fortunate that Byron died in his 36th year, for he would have become a reactionary bourgeois had he lived longer; conversely, they regret Shelley’s death at the age of 29, because he was a revolutionary through and through and would consistently have stood with the vanguard of socialism.

This puzzle has occupied scholars for decades: was Romanticism a revolutionary movement or a reactionary one? Like Napoleon, the hero of the Revolution who crowned himself Emperor, Romanticism can be seen from almost diametrically opposite perspectives. The movement was both.

Its solitary figure and foggy mountains don’t describe Romanticism as much as its capitalistic version

Born as a disruptive force in the wake of the biggest revolution the West has ever witnessed, early Romanticism eventually became the mainstream cultural atmosphere of 19th-century Europe. But, as it spread, the movement became contaminated by other forces that were moving across the continent at the same time: the birth of modern nationalism and the diffusion of a new, more pervasive form of capitalism.

By the end of the 19th century, Romanticism had moved from revolution to reaction, from fracture to restoration, from vitality to mannerism. And this is the same movement we can see in Friedrich’s paintings and life. Even as he remained obstinately faithful to his inner vision of nature infused with an unreachable God, he changed, probably despite himself. We see the result of that transformation in his most famous painting – a painting that we wrongly assume sums up everything that Romanticism has to offer. Its solitary figure and foggy mountains don’t describe Romanticism as much as they describe the reified, capitalistic version of the movement, which still casts its long shadow over us.

In some sense, this Wanderer obscures the powerful ideas that moved the first Romantics; it remains a dimmed version of the artistic ‘apocalypse’ of the Monk. The Jena Circle dreamt a world, but it’s not their dream we inhabit: as in some gnostic parable, the place we call home today is a corrupted, diminished version of that dream.

Every time we see it reflected in its thousand forms and distortions, the Wanderer reminds us that we are all Romantics at heart, whether we like it or not, and whether we know it or not. But if we look a little deeper into this almost-invisible and yet pervasive thing called Romanticism, we can find more than one version of the Romantic’s ideas. Beyond the Wanderer, we might find alternative visions – like the one embodied in Monk by the Sea with its sublime gaze into the apocalypse, into shapelessness, into the loss of self – to show us what history could have been, and maybe can still be, in fugitive moments of authentic and frightening freedom.