‘I was born in the land of the priests of Aksum,’ ZeraYacob is believed to have written in the 17th century. ‘But I am the son of a poor farmer in the district of Aksum.’ So begins the Hatata (a Ge’ez word meaning ‘enquiry’) of ZeraYacob, in which he documents his spiritual journey against a backdrop of intense religious controversy. He proceeds to reflect on the nature of God and human existence, the essence of evil and the basis of morality. A second Hatata, commonly attributed to WeldaHeywat, concentrates on issues of justice and moral truth. These two short texts are at the centre of Ethiopian philosophy. They have been generating intense controversy for generations because their authenticity and philosophical value have a crucial bearing on the very existence of Ethiopian philosophy and how it should be done.

There are, very roughly, two camps within Ethiopian philosophy today. The universalist approach to Ethiopian philosophy starts with the historical narrative that philosophy is a refined intellectual exercise that serves as a foundation for societal progress and individual enlightenment. This approach sees philosophy as one continuous dialogue, each philosopher learning from another in order to come up with new ideas. The universalist approach is founded on a cumulative and linear path that sees philosophy as starting at the time of the pre-Socratic philosophers, developing through the ideas of Socrates, Plato, Aristotle and the rest of the ancients, on to the medieval age, and finally into the modern era that was inaugurated by René Descartes and that is currently dominated by German and French Continental philosophy.

Other traditions of philosophy, such as the many strands of Indian philosophy, the philosophy of the Aztecs, the Japanese and the Chinese and so on, are, for the universalist, subsumed under the label of ‘comparative philosophy’. The value of non-Western philosophical traditions derives from what we might call an intercultural perspective. All philosophies are concerned with universal truths – all philosophies can be put into dialogue around this universal search for the conditions that make our existence possible and the reasons we have to live the way that we do. In general, the universalist position does not pay attention to the qualifiers of a tradition: it is not Indian or Aztec or Chinese philosophy that is at issue, but simply philosophy itself, philosophy as such.

The other camp we’ll call Africanist. For the Africanist way of doing Ethiopian philosophy, the history of philosophy is a process of deliberate exclusion that consists primarily in epistimicide – the systematic process of obliterating the knowledge system of the Other. In Africa, epistemicide was committed by colonisers in the name of disseminating the values of the Enlightenment and modernity. The Africanist approach sees itself as the saviour of, specifically, Africa and Ethiopia’s history. It is engaged in the search for a philosophy in the past that can serve as a foundation for cultural pride and recognition. Challenging the superior epistemic and cultural position that has been occupied by the West, Africanists see themselves primarily as countering the influence of Eurocentrism. In the words of Bekele Gutema, what is needed is ‘a robust understanding of philosophy that recognises the existence of philosophy in many cultures’.

The universalist camp charges the Africanists with blurring the distinction between the study of culture and the study of philosophy by trying to reduce philosophy into an ethnophilosophy (that is, the body of beliefs of a particular culture, usually indigenous, which is regarded as the expression of the collected beliefs of all the members of a given community and can be applied to the present moment without any change). In response, the Africanists see the universalists as worshipping the Eurocentric metaphysical structure and thereby losing sight of what it means to practise philosophy from a specifically African, Ethiopian and intercultural vantage point.

The essential question is this: should Ethiopian philosophy be practised from a universalist perspective – therefore taking Ethiopian philosophy to be part of the universal quest for wisdom – or from an Africanist perspective that sees Ethiopian philosophy as a means of cultural reaffirmation?

In 2022, I arrived at the University of Oxford to debate the very existence of Ethiopian philosophy: is there even such a thing that we can call ‘Ethiopian philosophy’? The conference was part of a renewed interest in Ethiopian philosophy spurred on by the widespread interest in the Hatatas. I was once an Africanist philosopher who believed that the Hatatas of ZeraYacob and WeldaHeywat served as the foundation of an indigenous Ethiopian philosophy. But, after coming across the works of the French historian Anaïs Wion and the Ethiopian politician Daniel Kibret, I abandoned that position. The more I looked at the Hatatas, the more I came to believe that the texts are plagued by questions over authorship and that the debate over their philosophical value is driven by ideology rather than genuine discussions on the value of philosophical wisdom. I don’t believe they can serve as the basis of an indigenous Ethiopian philosophy.

The defenders of the Hatatas desperately want to show the existence of a Cartesian form of subjectivity found on the African soil. They believe that finding an African who sees the world in terms of the isolated form of subjectivity made influential by Descartes’s Cogito, ergo sum (‘I think, therefore I am’) is tantamount to proving the existence of indigenous philosophy in Africa. But this is a futile exercise. The real aim of the Hatatas is the attainment of religious renewal through the reformation of existing religious practices – which has nothing to do with the intrepid voyage of self-discovery that was undertaken by the 17th-century Frenchman sitting next to his fireplace.

I was an Ethiopian who stood against the very idea of an Ethiopian philosophy solely based on the Hatatas

There are problems on a textual level as well, such as the many striking similarities between the writing style of ZeraYacob and WeldaHeywat and that of the true author, a 19th-century Catholic missionary named Giusto d’Urbino. ZeraYacob, for instance, describes his wife in almost exactly the same way as D’Urbino describes his maid: the Christian name of both is Werke; their conception of labour and the way in which both detail their journey from Aksum to Gonder are suspiciously similar. But most damning is that the ardent supporters of the Hatatas are Africanists who are motivated by nationalism rather than an attempt to study the philosophical value of the teachings found in the texts.

So in Oxford I found myself in an unusual position: an Ethiopian who stood against the very idea of an Ethiopian philosophy that is solely based on the Hatatas. I was instead a defender of the Western philosophical tradition, entering into a heated debate with the ardent supporters of Pan-Africanism and decolonisation who are trying to provide a political – not philosophical or historical – defence of the Hatatas. For me, the real value of philosophy is not found in the creation of a fictitious past, invented only in order to be wielded against the Western philosophical tradition.

The debate I had with the defenders of the philosophical value of the Hatatas made me realise that, even if the Hatatas cannot serve as the foundation for an indigenous Ethiopian philosophy, there is still, today, a unique position that is occupied by Ethiopian philosophy in the context of the wider development of a philosophical culture on African soil. Until Ethiopian philosophy is able to make sense of the prospects and pitfalls that are a part of its unique position, there will never be progress in developing a socially grounded philosophical practice.

What is the unique position of Ethiopia? As the historian Teshale Tibebu wrote: ‘Ethiopia is a historically antique polity. It is one of the very few places that managed to sustain an unbroken chain of historical civilisation free of foreign “corruption”.’ Since the country has never been colonised, it boasts a history of independence that stretches back to distant antiquity. (The only time it came close to becoming a colony was during the five-year occupation by Mussolini’s troops in the 1930s.) Ethiopia is a nation where there are both written and oral sources of wisdom, which can serve as rich material for philosophical reflection. And it is a state whose history cannot easily be subsumed into the model of the European state, since its trajectory developed in a fascinatingly complex entanglement of Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Western and Arabic traditions. All of this means that there is a need to develop a foundation for philosophical analysis that is not only focused on decolonisation.

Hand in hand with the need to develop a conception of Ethiopian philosophy that is cognisant of such complexity, there is also a need to develop an Ethiopian philosophy that is not influenced by government ideology. Ever since modern academic philosophy was introduced in the 1950s, it has had to contend with political pressure. During the Imperial regime, which lasted until 1974, the goal of modernisation dictated the practice of philosophy. After Haile Selassie was overthrown in a coup d’etat and the Derg era began, the inculcation of the basic teachings of Marxism-Leninism gained momentum, and philosophy that strayed from the party line fell drastically out of favour. After the Derg’s legacy government fell in 1991 and the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) took its place, philosophy remained a primarily ideological instrument, though the goal now was to take ethnic identity as an organising principle of the Ethiopian federation. The EPRDF aimed to reduce all academic disciplines, including philosophy, to mere tools for realising the motifs of revolutionary and developmental democracy. It was against this background that I myself was introduced to the world of philosophy.

This questionably assumes that philosophical wisdom can be passed down in the form of sayings and proverbs

When I joined the Department of Philosophy at Addis Ababa University in 2005 as an undergraduate student, I became immersed in an intellectual environment that was deeply under the sway of Continental philosophy while also trying to break away from the Western epistemic structure by introducing an intercultural exchange founded on the study of Ethiopian, African and Eastern philosophical perspectives. I also found the lasting influence of two models of philosophising that were led by Claude Sumner and Messay Kebede.

Kebede was a former chairperson of the Department of Philosophy, which during the Derg period he attempted to guide towards Marxist-Leninism. After the EPRDF regime came to power, he was expelled, along with other university professors, because of his political views. In his works Survival and Modernization (1999) and Radicalism and Cultural Dislocation in Ethiopia, 1960-1974 (2008), Kebede identified contradictions in modern Ethiopia and the ways in which an alternative conception of societal modernisation could be realised. His view of the Hatatas is instructive: he believed that the texts were authored by Ethiopians, but that ZeraYacob was not himself a genuine philosopher. Instead, ZeraYacob’s aim was to provide a foundation for national unity through criticism of the Church’s teachings.

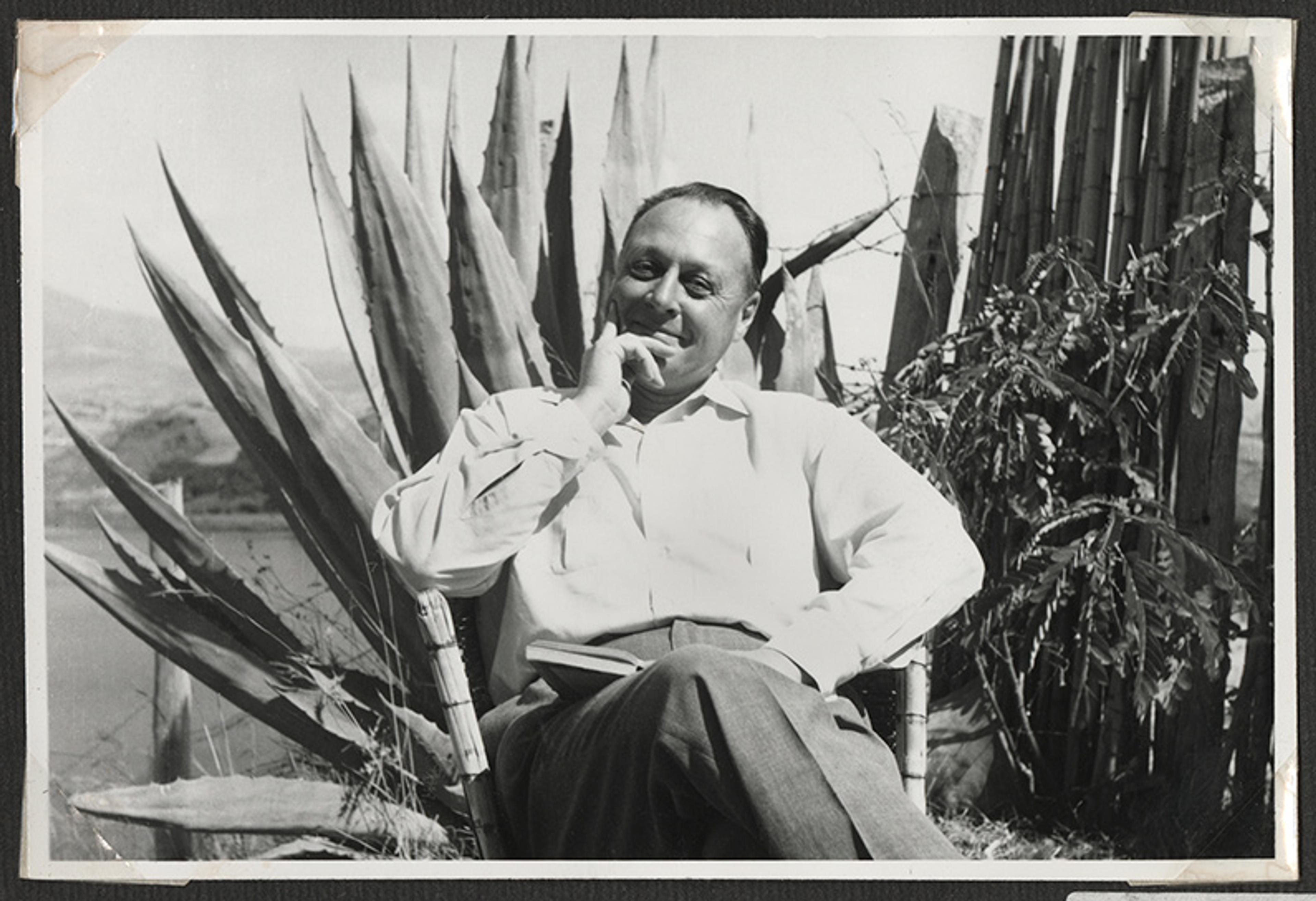

Claude Sumner picture in the 1960s. Courtesy the Archive of the Jesuits in Canada

Sumner, meanwhile, was a Canadian philosopher who lived in Ethiopia for decades. He believed that Ethiopian philosophy expresses itself in three ways. The first is the written sources of Ethiopian philosophy found in the Hatatas. The second is the study of foreign philosophical wisdom that is creatively introduced onto the Ethiopian soil, which Sumner himself pursued in his epic multi-volume study Ethiopian Philosophy (1974-1978). And the third is the oral sources of Ethiopian philosophy, explored by Sumner in his Oromo Wisdom Literature: Proverbs, Collection and Analysis (1995). Ethiopian philosophy, according to him, occupies a unique place in African philosophy since it is made up of both oral and written traditions. (This somewhat questionably assumes that philosophical wisdom can be passed down from one generation into the other in the form of sayings and proverbs.) Sumner was not in the Africanist camp. He did not want to identify with a relativist discourse that loses sight of the interconnections that are found among different conceptions of truth, and he strongly believed in the benefits of a cross-cultural examination of the Hatatas, as well as that of canonical Western philosophers like Descartes and Kant.

After the EPRDF regime came to power in 1991, they closed the Department of Philosophy because it was deemed not to contribute to ‘development’. In 2002, it reopened after faculty members sought to show that philosophy is indeed useful in analysing societal problems, with a curriculum that was heavily influenced by Continental philosophy but which also hosted a creative tension between universalist and Africanist approaches. Perhaps the most prominent universalist philosopher of the time was the late Andreas Esheté, a hugely influential public intellectual who had studied at Yale and was involved in the experiments in federalism that Ethiopians were then undertaking (he later served as the president of Addis Ababa University). Dagnachew Assefa, another universalist, studied at Boston College and believed that the ideas of Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre could be used to develop an analysis of contemporary Ethiopian problems. Assefa also emphasised the value of philosophy in the public sphere and the usage of philosophical categories to analyse existing predicaments.

The one way of doing philosophy that was not given any attention, by the way, was the analytic tradition. In a nation where the production of knowledge is highly influenced by Marxism and the need to make an actual intervention into existing human relations, no meaningful interest in analytic philosophy developed. This lack of interest can also be explained by the fact that all of the major Ethiopian philosophers, whether universalist or Africanist, were educated in Western universities heavily influenced by Continental philosophy.

Ultimately, the Hatatas – whether or not they can authentically be ascribed to ZeraYacob and WeldaHeywat – occupy a crucial place in the attempt to understand the nature of Ethiopian philosophy for both universalists and Africanists. The universalists see philosophy as a reflection on the human condition, and, if there is philosophical wisdom in the Hatatas, then it needs to be separated from nationalistic sentiments. The Africanists value the role played by the Hatatas in the process of decolonisation and the challenge they pose to the epistemic privilege enjoyed by the West.

The Africanist approach ends up being an anti-Eurocentric Eurocentric discourse

In this debate, I believe that the Hatatas provide a space for reflection on the ways in which Ethiopian philosophy can be practised, even if it doesn’t serve as the foundation of that philosophy. There is still a need to make sure that a philosophical analysis of contemporary predicaments is given attention and that the whole idea of an Ethiopian philosophy is not fixated on the idea of texts that may or may not have been written by Ethiopians. As an alternative, following the radical Beninese thinker Paulin Hountondji’s understanding of philosophy as a field of contestation and an active process of construction, we should view Ethiopian philosophy as a field that is still emerging through a dialogue between the hermeneutic, the intercultural, the critical theory and the Indigenous trends. Despite the antiquity of Ethiopia, its philosophy is just getting started.

Attempts have also been made by thinkers like Kebede and Maimire Mennasemay to lay the foundations for the development of a critical Ethiopian social theory, which attempts to move beyond the universalist/Africanist divide. Abandoning his earlier commitments to Marxism, Kebede introduced a new approach that applies philosophical categories to the analysis of issues like modernisation, ethnic politics, education and development. Mennasemay, in his creative engagements with Ethiopian history, has tried to demonstrate the need for Ethiopian political theory to indigenise the universal values ideas of democracy.

As someone who had always been more interested in Continental philosophy, I’ve always been more interested in the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche, Heidegger and Jürgen Habermas rather than of a fully formed philosophy from the past – like ZeraYacob’s – that can now be applied as the solution to all of our contemporary problems. I long viewed the idea of an African philosophy and the practice of Ethiopian philosophy from Africanised perspectives with scepticism. I saw it as obsessed with a meta-level discourse that is content to merely engage in a critique of the colonial sciences. As the Congolese philosopher V Y Mudimbe shows, the Africanist approach ends up being an anti-Eurocentric Eurocentric discourse: it is so preoccupied with being anti-Eurocentric that, ironically, it remains Eurocentric, performing a contradiction rather than producing works of philosophy that grapple with our existential predicaments. But I’ve come to see that there are issues with the universalist camp as well. It has not paid enough attention to the lived experience and emancipatory struggles that Ethiopians share with fellow Africans. Since it aims at participating in a universal sense of subjectivity not founded on a proper historical consciousness, it loses sight of our distinct Africanness and the shared horizon within which our common destiny unfolds.

It’s an important feature that many of the discussions and debates about Ethiopian philosophy are led by anthropologists. I take this development with a grain of salt. Because of the nature of anthropology, there is a danger in elevating each and every worldview and system of belief into the status of ‘philosophy’: we could lose sight of what it is that makes some forms of enquiry uniquely philosophical. It is the anthropologist’s goal to understand different worldviews as they function in and of themselves, without regard to their truth or their consequences. But philosophers, to my mind, need to concern themselves with things like truth and coherence. (This tension is reminiscent of the debate between Habermas and Jacques Derrida on the nature of philosophy and texts, in which Derrida argued that works of literature are also materials for a philosophical reflection, and Habermas rejoined that this view would constitute an abandonment of the rational power of reason.) Still, such a form of universalism is the exact thing that the Africanists identify with Eurocentric thinking, and that is why there is a need to develop a conception of Ethiopian philosophy that is cognisant of both Africanness and also a sense of universality.

If Ethiopian philosophy is to make any form of progress, it needs to take part in the discussion of African philosophy as well as the universal quest for knowledge. This cannot be attained through studying only the past or, on the other hand, abandoning history and human values in the name of universality. It is not just the Hatatas but also the analysis of contemporary issues that need to be accommodated into the study of Ethiopian philosophy. At the same time, Ethiopian philosophers shouldn’t blur the distinction between philosophy and anthropology in the name of engaging in a socially grounded philosophical practice.

In the end, the enquiry into the unique position of Ethiopian philosophy tells us that philosophy is a discipline that can be practised in different historical horizons and geographical spaces – while, at the same time, it retains the capacity to illuminate the universal human condition. However it is perceived, philosophy should not be seen as a simple tool of resistance that does not give us the ability to reflect on broader questions about the nature of reality, knowledge, truth and human values.

The problem that Ethiopian philosophy continues to struggle with is that it has been practised under a politicised debate more interested in exposing the racial or colonial undertones that are found in the existing philosophical tradition than in setting the stage for the development of a culture of criticism able to make sense of our predicaments. Any conception of Ethiopian philosophy that has the power to speak to contemporary problems needs to be founded on the recognition that there is an engagement among different philosophical traditions, and that it is through a process of mutation that different ways of doing philosophy assume their current form.