Dusk, that most beautiful moment

With no pattern.

Millions of images appear and disappear.

Beloved people.

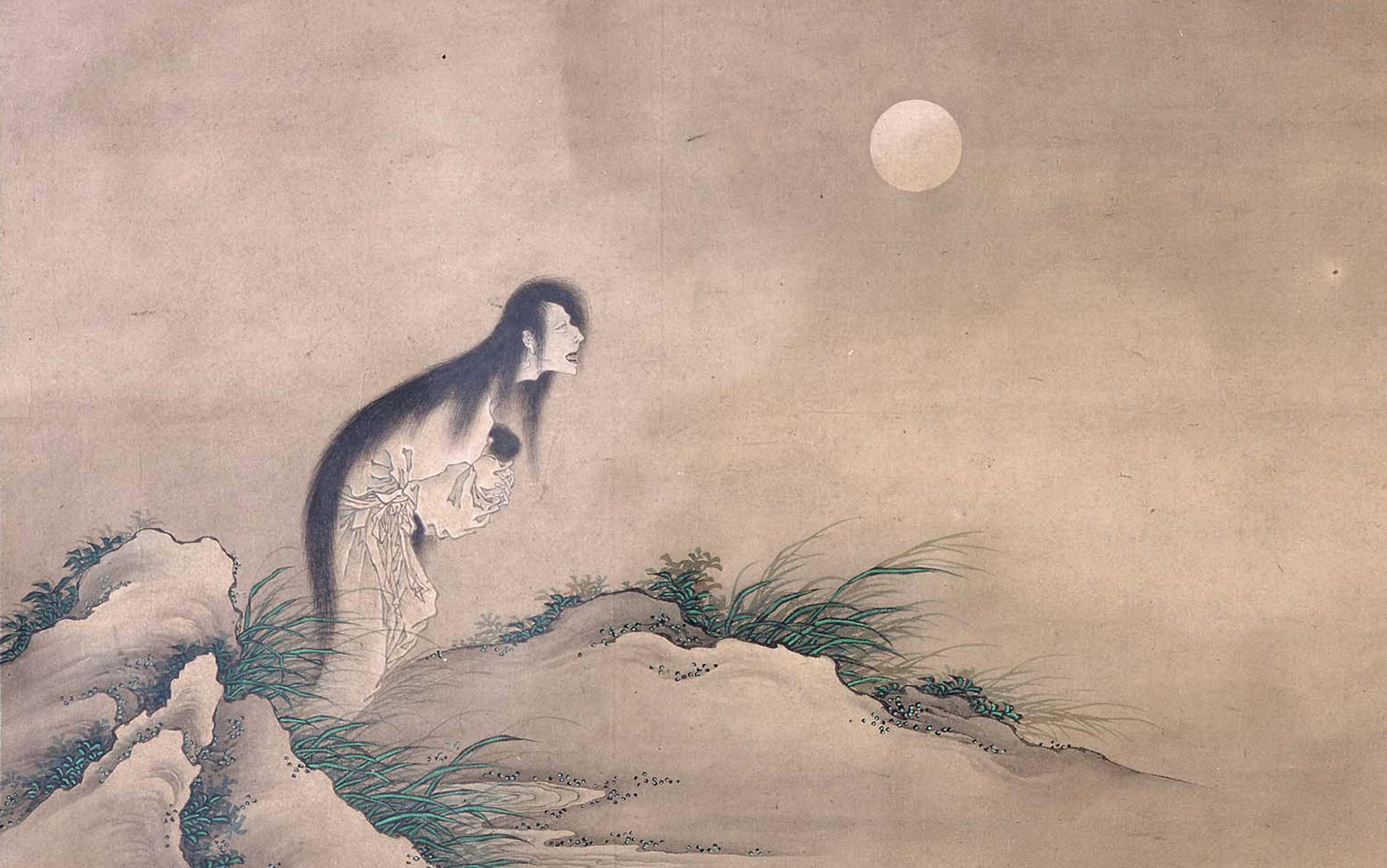

How unbearable to die in the sky.

Hours after writing these lines, the 24-year-old Tadao Hayashi fuelled a battered Mitsubishi A6M Zero and flew it towards an American aircraft carrier – and into nothingness. It was late July 1945. A few days later, the United States would drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A war sold to the Japanese public as a struggle for national survival would be over.

In contemporary Western memory, still stocked for the most part by wartime propaganda imagery of mad, rodent-like Japanese, those final weeks are a swirl of brainwashed fanaticism, reaching its apotheosis as hundreds of kamikaze planes slammed into the US ships closing in around Japan’s home islands. Three thousand raids and innumerable scouting missions were launched during the climax of the conflict, designed to show the US the terrible cost it would pay for an all-out invasion of Japan.

Yet the vast majority of planes never made it to their attack or reconnaissance targets; they were lost instead at sea. And war’s end failed to yield the apocalyptic romance for which Japan’s leaders so fervently hoped. By late 1944 and early ’45, the only ‘life or death struggle’ was the routine misery to which the empire itself had reduced its soldiers and civilians. Conscripts were trained and goaded to fire their rifles into their own heads, to gather around an activated grenade, to charge into Allied machine-gun fire. Civilians jumped off cliffs, as Saipan and later Okinawa were taken by the Allies. Citizens of great cities such as Tokyo and Osaka had their buildings torn town and turned into ammunition.

Nor do clichés of unthinking ultranationalism fit the experiences of many kamikaze pilots. For each one willing to crash-dive the bridge of a US ship mouthing militarist one-liners, others lived and died less gloriously: cursing their leaders, rioting in their barracks or forcing their planes into the sea. A few took their senninbari – thousand-stitch sashes, each stitch sewn by a different well-wisher – and burned them in disgust. At least one pilot turned back on his final flight and strafed his commanding officers.

And then there were the university students. Hundreds of thousands of young men such as Tadao Hayashi were pulled from lives of Goethe and Flaubert, classical music concerts and debates about Marxism, and forced to enlist. Around 1,000 of them ended up on kamikaze missions, alongside boys of a similar age who had never got further than elementary school. Earlier in the war, university students had been able to put off conscription while they studied. By the autumn of 1943, only those majoring in science or education retained that privilege, so desperate were Japan’s leaders for recruits.

By day these student pilots were beaten – often unconscious – by superiors and non-student conscripts who resented their privilege. By night, they wrote: letters, diaries, poetry, struggling to imagine being here today and not tomorrow, to justify their own deaths in the way they had been taught by their leaders. Wasn’t Japan a nation under threat of extinction, hemmed in spiritually and strategically by the US and Britain? Weren’t they obliged to defend their people and values against the nihilistic hyper-individualism of two once-great nations?

Most of these students were a good deal more sophisticated than the ideologues who ranted to them about the evils of Western materialism. But wartime caricature had its roots in peacetime critique. Ever since the 1890s, Japanese scholars had warned that Western metaphysics, epistemology and morality were so profoundly hard-wired into the technological culture of the US and Europe that, by importing this culture, Japan had let in all the rest and stood now on the verge of forgetting itself.

How did Japanese intellectuals let an anxiety become a call to arms? It is hard enough to analyse the process in retrospect, the dust of conflict having long ago settled. For many student soldiers living through the drama of 1944 and ’45, this sort of discernment was simply beyond them. In search of meaning, they fled the vacuous slogans of the military, only to end up in the embrace of pioneering thinkers whose distinctly ‘Japanese’ philosophy increasingly pointed in just one direction: the battlefield.

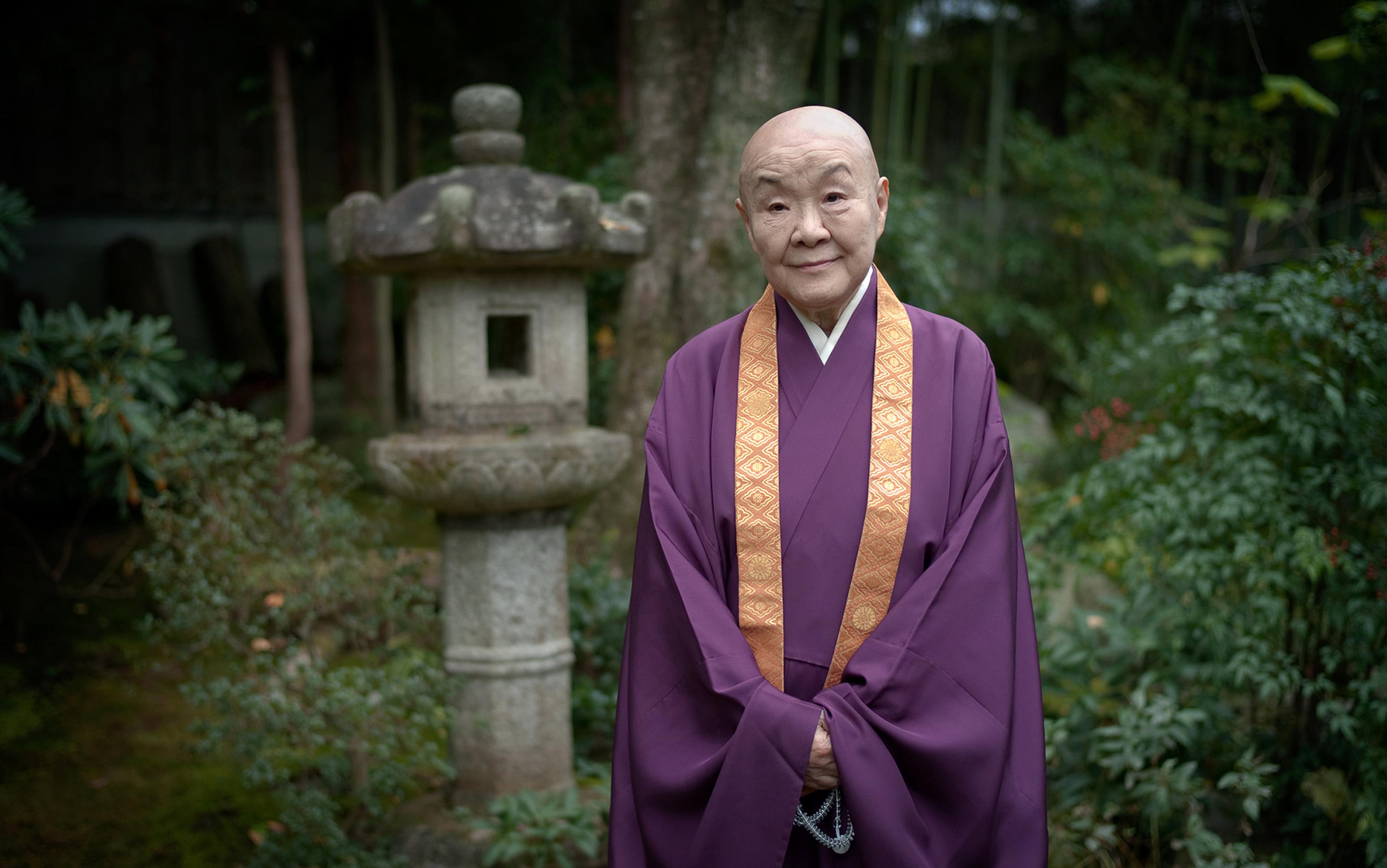

One of the most ambitious schemes for a Japanese philosophy – where nothing by that name had existed before – was emerging at Hayashi’s own institution in 1943, just when he was forcibly removed from it. The great project of Kitarō Nishida, a seasoned Zen practitioner and the founder of what became the ‘Kyoto School’ of philosophy at Kyoto Imperial University, was to do what many Zen Buddhists insisted was impossible: to describe the picture of reality revealed in meditation.

Nishida sought to reverse the key premise of Western philosophy, writing not about ‘being’ or ‘what is’, but instead about ‘nothingness’. His was not the relative nothingness of non-being – the world of the gone-away, the not-yet or the might-be. He meant absolute nothingness: an unfathomable ‘place’ or horizon upon which both being and non-being arise.

To help students make sense of this idea, Nishida liked to draw a cluster of small circles on the lecture-hall board. This is how people usually see the world, he would say: a collection of objects, and judgments about those objects. Take a simple sentence: ‘The flower is yellow.’ We tend to focus on the flower, reinforcing in the process the idea that objects are somehow primary. But what if we turn it around, focusing instead on the quality of yellowness? What if we say to ourselves ‘the flower is yellow’, and allow ourselves to become perceptually engrossed in that yellowness? Something interesting happens: our concern with the ‘is-ness’ of the flower, and also the is-ness of ourselves, begins to recede. By making ‘yellowness’ the subject of our investigation – trying to complete the sentence ‘Yellowness is…’ – we end up thinking not in terms of substance, but in terms of place. The question isn’t so much ‘What is yellowness?’ as ‘Where is yellowness?’ Against what broader backdrop does ‘yellowness’ emerge?

For Nishida, the answer was a special sort of consciousness: not first-person reflection, where consciousness is the possession of an individual, but rather a consciousness that possesses people. It becomes less true to say that ‘an individual has experiences’ than that ‘experience has individuals’.

‘Absolute nothingness’, after all, is not an idea to be grasped: it is a provocation, a literal insult to the intelligence

But if consciousness is the horizon beyond ‘yellow’, what is the further horizon? Where is consciousness? Nishida drew a dotted, all-encompassing line on the board. This, he said, is ‘absolute nothingness’, producing and interpenetrating every other plane of reality. Absolute nothingness is God. And God is absolute nothingness.

One wonders how many students filed out of Nishida’s lecture hall thinking: ‘A-ha! Now I get it!’ They could surely be forgiven for trying to understand absolute nothingness the same way we understand most things: by making it into an object of thought, placing ourselves outside it and perusing it from all angles. Yet a nothingness to which you could do this would not be absolute: it would just be one among that cluster of small circles on the board.

Nishida probably wouldn’t have minded such doomed attempts at understanding. ‘Absolute nothingness’, after all, is not an idea to be grasped: it is a provocation, a literal insult to the intelligence. It was already de rigueur in the Zen circles of Nishida’s day to scoff at the limited reach of conceptual knowing, treasuring instead the koan, the meditation cushion and the knowing look. But Nishida and his colleagues in the Kyoto School preferred not to write it off until it had been tested to the limits – tested, one might say, to destruction. ‘Absolute nothingness’ had the potential to perform that function. It promised to bring about the realisation that the idea of knowledge ‘from the outside’ must largely be a fiction.

The trouble was, as an idea, it had other sorts of potential too. The war was dragging on. Japan’s chances of winning – or even achieving a respectable peace – were fading. There is a fine line between understanding an idea such as ‘absolute nothingness’ and deploying it as a rationalisation, and it appears that Nishida and his colleagues crossed it – and encouraged their readers to do so, too. A relatively abstract set of ideas were allowed to take on potent political form.

Neither Nishida nor his great friend and rival Hajime Tanabe – who trained with Martin Heidegger before joining Nishida at Kyoto – ever put their talents unreservedly at the service of Japan’s political leaders. Tanabe was in fact an early and vocal critic of Heidegger’s involvement with Nazism. But caught up in Japan’s crisis, and fearful of following fellow academics who equivocated in their support for the regime out of their university posts and into the jail cells of the ‘Special Higher Police’, they began to explore how metaphysics, politics, and war might fit together.

Nishida, a one-time devotee of Hegel and Heidegger, returned to his Zen Buddhist roots to ask whether mistaken subject-object dualisms in human thinking – that cluster of circles on the lecture-hall board – might be to blame for Western nations’ ‘imperialist squabbling’. A case of politics rooted in culture, rooted in turn in an error of perception.

Tanabe went much further. By what means, he asked, does absolute nothingness manifest itself in the world of being? Not directly, in an individual’s inner life. No, between absolute nothingness and the individual there must be some kind of mediating power. Looking around, Tanabe saw only one obvious candidate. ‘God does not act directly on the individual,’ he wrote. ‘The salvation of the individual is accomplished through the mediation of nation and society.’

talk of ‘the’ nation turned to talk of ‘our’ nation, its ultimate symbolisation in the emperor, and even the possible necessity of death in the service of both

This was still a fairly innocuous observation about how Japan was being held back by what Tanabe regarded as a clan mentality: people brought up in a closed society were struggling to open themselves to the wider world. The trouble, in a sense, was that they were poor internationalists. And Tanabe owed as much here to Hegel as to Buddhism – he understood individual lives to be shaped entirely by the ebb and flow of historical time, itself part of a great metaphysical unfolding.

Things changed, however, when Tanabe started to insist on the nation as the fundamental context in which individuals and society mediate one another, the realm in which individuals work out their salvation. Perhaps the nation was what made philosophy possible at all. Then talk of ‘the’ nation turned to talk of ‘our’ nation, its ultimate symbolisation in the emperor, and even the possible necessity of death in the service of both. ‘Our nation is the supreme archetype of existence,’ Tanabe concluded. (His one-time mentor, Nishida, is rumoured to have whispered to a friend: ‘This Tanabe stuff is completely fascist!’)

The same dark times that rendered two of Japan’s best-known philosophers unusually susceptible to political and public pressure softened up students for their grand ideas and bold claims. In the spring of 1943, Tadao Hayashi went to see Tanabe lecture. ‘The only salvation for us, according to Professor T, is to realise that one must die,’ he wrote with enthusiasm in his diary. ‘We should live our lives prepared to plunge into death at any moment… Professor T [said] … that humans and God do not come into direct contact. Instead, a nation mediates between the two’.

Months later, when Hayashi was drafted to serve that nation, Tanabe had this message for him and his fellow student conscripts:

You are to learn the spirit of the Imperial Army… which is none other than the quintessential flowering of the spirit of the nation… Take the lead in breaking through the pass between life and death… By serving the honourable callings of the Sovereign as the one whose person brings together God and country, you will share in the creation of the eternal life of the state. Is this not truly the highest glory?

Tanabe’s words were now not far off the surreal language of a kamikaze training manual, aimed at the sort of people who liked to beat up the Hayashis of this world for being too smart:

Do your best. Every deity and the spirits of your dead comrades are watching you intently. It is essential that you do not shut your eyes for a moment so as not to miss the target. Many have crashed into the targets with wide-open eyes. They will tell you what fun they had.

No wonder that the last letters and diary entries of young men such as Hayashi were full of confusions and contradictions. They were summoning all the resources of an elite education to try to cast their tragic situations in a meaningful light. For the most part, they failed. At their most convincing, they set politics and philosophy aside and invested themselves instead in letters to their families – and particularly to their mothers. ‘I am happy to go,’ wrote one pilot to his mother, ‘but I begin to cry when I think of you. I want to be held in your arms and sleep… I have a great deal more to say, but I will stop here. [Tomorrow is] the final sortie. Goodbye.’

As his students piloted their Zeros out towards the sea in 1944, Tanabe sat at home, trying to decide whether the time had at last come to speak out against the conflict, influential figure that he was. Could he help to achieve a surrender? Or would an intervention merely place Japan in even greater peril? The more Tanabe tried to find a rational answer, the more frustrated he became with himself and with the pursuit of philosophy altogether. What was the point of it, if it offered no answers at precisely the moment they were most needed?

In the end, the strain caused something to break inside him, and he found himself flooded with what he later called zange: repentance. It was a shattering encounter with the power of absolute nothingness, not as the ‘place’ talked about by Nishida but as the dynamic ‘Other-power’ in which many Japanese shinshū Buddhists placed their faith. The result was a new and totally foreign sense of self – one that was ‘given’ and raw, rather than owned and honed. Tanabe was moved to adapt the words of St Paul: ‘It seems no longer I who pursue philosophy, but zange that thinks through me’.

Finally now renouncing his old assertions about the Japanese nation, and working behind the scenes to try to end the war, Tanabe felt that nothing less than human reason itself had been ‘shattered’ inside him. Human will, too: his new ‘absolute critique’ of reason implied a total admission of defeat, on all fronts. Everything had to go.

For Tanabe’s critics, these dramatic events came too late, and in Japan’s bitter post-war accounting he was numbered amongst those – lawyers, philosophers, novelists, cultural critics – who could have spoken out against the war but chose not to. Worse, he had actively peddled what one critic called a ‘philosophy of death’.

Were Tanabe’s simply a darkness-into-light conversion story, one would certainly find the convenience of its timing suspect, and its dismissal of reason a little humdrum. But this picture of surrender and insight, reason and rationalisation, was at once less hopeful and more compelling.

The search for a truly ‘Japanese’ philosophy ended instead with a picture of the human condition as caught between death and rebirth

For a start, humans don’t turn their backs on reason, Tanabe insisted. It has its obvious merits, and to imagine that we’re not stuck with it as a fundamental part of who we are is to become lost in mystical fantasy. Rather than give up on it, we have to reason at full-throttle – until it gives up on us. Until the plane breaks apart or careers into the sea. Only at that point might we find ourselves so completely humiliated, so bereft of slogans and comforting stories to tell ourselves, that we dissolve into ‘absolute nothingness’, and absolute nothingness works unimpeded through what is left.

Even then, the journey is not over. Tanabe discovered something in himself that sought always to possess any new experience or idea, no matter how profound or engrossing. A desire to manage life from the margins soon reasserted itself, deploying insights rather than sacrificing oneself to them. Tanabe’s was not, then, a philosophy of death, nor even of death and rebirth. The search for a truly ‘Japanese’ philosophy ended instead, for him, with a picture of the human condition as caught between an unsought shattering in zange and an unwanted re-formation of the pieces – back and forth between death and rebirth.

It is hard to fathom Tanabe’s reasons for never apologising clearly over the ultranationalist turn that his wartime thought briefly took. But part of the story might have been this: after August 1945, he saw people all around him making apologies, hurriedly drawing lines under the past – trying to turn darkness into light. And all the while Tanabe’s best guess, hard won, was that such shifts simply don’t last. Sooner or later the darkness will be back.