On 18 May 1904, in a village near Japan’s Sagami Bay, looking out to the white peak of Mt Fuji, the son of a Buddhist priest was born. Shunryu Suzuki grew up amid the quiet rituals of Sōtō Zen, a tradition that prized stillness, repetition and near-imperceptible spiritual refinement. When he wasn’t sweeping temple courtyards, he was studying, preparing to follow in his father’s footsteps. But then, at age 55, after a life steeped in the disciplines of Japanese Zen, Suzuki travelled to San Francisco.

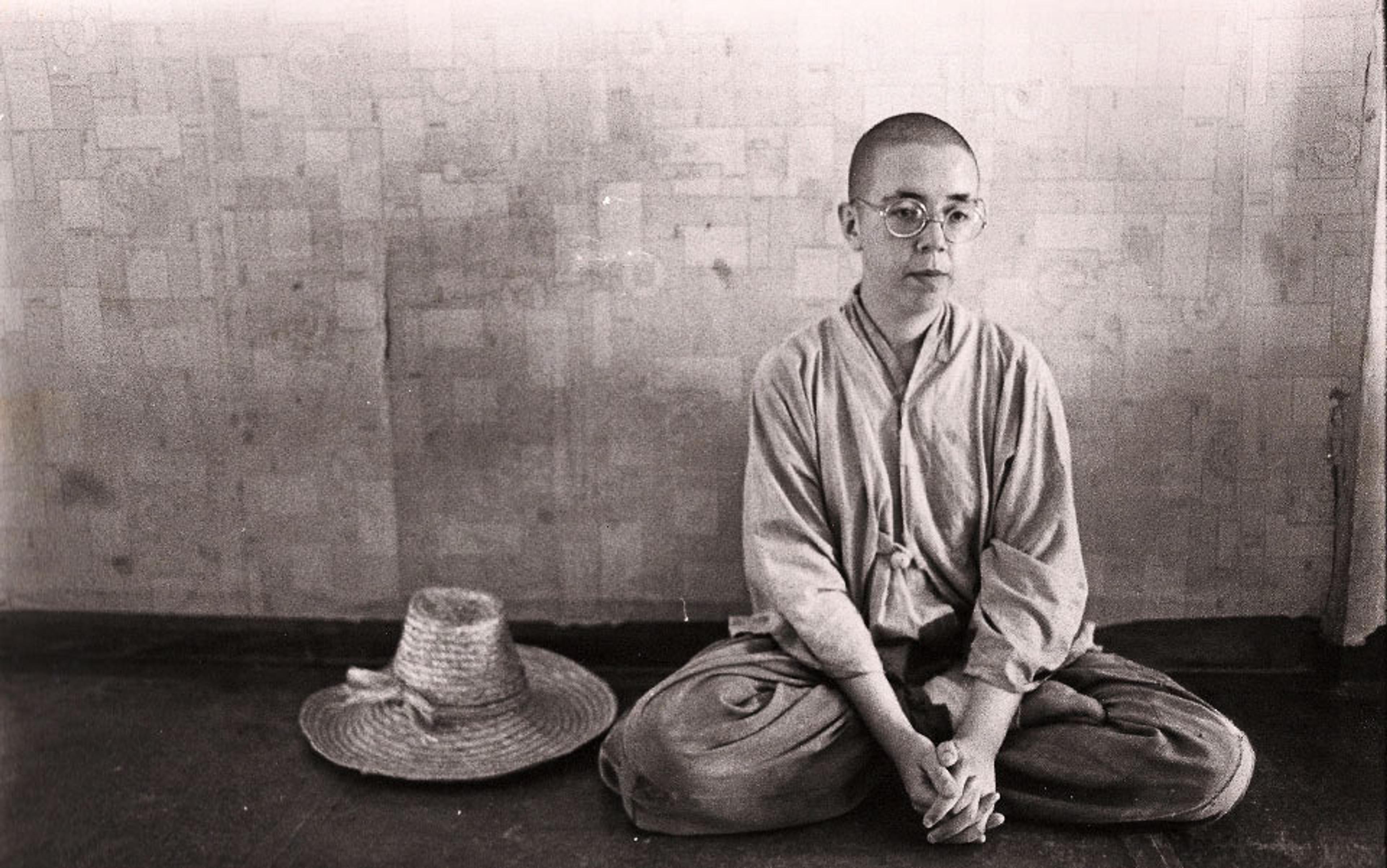

Shunryu Suzuki in his dokusan and study room in San Francisco, c1970. Photo by Katherine Thanas

He arrived in California in 1959, as the United States’ literary counterculture was turning toward ‘The East’ in search of new ideas. Alan Watts had already begun to popularise this turn through The Way of Zen (1957), a book that offered Americans liberation from the disillusionment and disorientation of the 20th century. A former Anglican priest with a taste for LSD, Watts presented Eastern ideas as a corrective to Western striving. For him, Zen was a way of ‘dissolving what seemed to be the most oppressive human problems’. It offered liberation from the strictures of social conditioning, convention, self-consciousness and even time. Others began to take notice, too. In California, the austere discipline of Japanese monasticism was being reimagined in a new milieu alive with jazz, psychedelics and endless seekers looking for ways to fix the human condition, or at least their own case of it.

Suzuki arrived in California with answers. At a dilapidated temple founded for Japanese immigrants in San Francisco’s Japantown, he slowly defined the trajectory of Zen in the US. ‘Just sit,’ he told his followers. ‘Just breathe.’ As this spiritual practice entered the chrome-lit sprawl of postwar US, it became a new tool for artists, poets, dropouts, bohemians: a technology for awakening. It found kinship, perhaps uneasily, with the Human Potential Movement then flourishing down the coast at the Esalen Institute, where encounter groups, psychedelics and primal scream therapy were all aimed at cultivating a more expansive idea of human flourishing. In this new setting, Zen slotted neatly into the dream of total transformation. Enlightenment was no longer a mountaintop ordeal. Instead, it became a weekend workshop, a practice, a form of self-help.

But Suzuki’s original path, the one he learned in Japan, appeared to point elsewhere. Real awakening seemed to demand isolation, silence, the stripping away of ordinary life. It required years in robes, cold zendō (meditation halls), endless chanting, discipline with no immediate reward. This ‘old’ version of Zen was monastic at its core. And so, in the US, Zen seemed to split, quietly, in two. On one side, a casual practice adapted to modern lives; on the other, a pursuit of true enlightenment, suited only to those who could withdraw.

This was the complicated spiritual world I was born into: a world of Californian counterculture and Sōtō Zen austerity. And soon, it would set me on a tangled path of my own. Could I follow the ancient route to awakening and still live fully in the world, with all its noise, its complexity, its folly?

I first encountered Zen in the late 1960s when my mother, hoping to make me a better, or at least more bearable, person than the obnoxious middle-school boy I undoubtedly was, dragged me to a group meditation session, known as a ‘sit’, at a community preschool in our hometown of Mill Valley, just north of San Francisco. The sit was hosted by a student of Suzuki’s named Jakusho Kwong.

By this time, Suzuki had been in the Bay Area for roughly 10 years and was no longer ministering only to the immigrant and Nisei (or second-generation) communities in Japantown. By 1967, he had helped open the San Francisco Zen Center and had purchased a mountain retreat (named Zenshin-ji, ‘Zen Mind Temple’) near Big Sur. He was also about to acquire an urban temple in San Francisco that would be called Hosshin-ji, ‘Beginner’s Mind Temple’. His students, like Jakusho, were beginning to spread Zen far and wide across California to followers who were overwhelmingly young, white and (mostly) hip.

Shunryu Suzuki (front, left) alongside teachers and officers at the Tassajara Zen Mountain Centre near Big Sur, California, c1970. Courtesy shunryusuzuki.com

That early morning in Mill Valley, I remember Jakusho stalking around the room, striking sleepy or slouching students with the keisaku (‘wake-up stick’). Each time he came around to me, sighing, he would bend down and straighten my back against the stick in a firm but gentle way. I was relieved not to be hit, but also embarrassed and oddly comforted by his touch.

They gave me LSD when I was 14 or so. I mostly remember a beautiful, dizzying day full of sun and music

My mother also practised with Suzuki at his mountain retreat, and I came with her one afternoon. I remember one thing from the visit. When we arrived, she stopped the car at the entrance and got out to speak with a monk wearing full robes. They had a brief conversation and the monk, probably responding to a simple question like ‘Where should I park?’, stood back and pointed. Something about the gesture was compelling: the tall, thin man in black with a shaved head pointing as if to say: ‘That is the Way you should go!’

Shunryu Suzuki, Los Altos Hills, California, c1964. Courtesy ShunryuSuzuki.com

These early, fleeting glimpses of Zen were accompanied by massive doses of the conceptual framing that surrounds Buddhism. My parents had met Alan Watts and his young family through the same preschool in Mill Valley where I first learned to meditate as a child. My father was also friends with the author Dennis Murphy and, through him, met his brother Michael Murphy, the co-founder of the Esalen Institute. Michael introduced my parents to a long list of movers and shakers in the Human Potential Movement, a countercultural spiritual and psychological movement that had drawn in the likes of Aldous Huxley and the Beatles. It was Murphy who invited my parents to observe and participate in early experiments with psychedelic drugs, including LSD and psilocybin. Our family spent a bit of time at Esalen, engaging in ‘encounter sessions’ and other experiences favoured by the Movement. As part of the programme, my parents also experimented on me: with my consent, they gave me LSD when I was 14 or so. I mostly remember a beautiful, dizzying day full of sun and music. The world was shiny, and it danced with images the like of which I had never seen.

My parents and their friends never really stopped talking, and when the conversation turned to Zen, there was a flood of information and questions about enlightenment. How could someone ‘get’ it? What did ‘getting enlightened’ actually mean? The picture that emerged was of a lasting state attained in a flash, usually due to a profound shift in perception or understanding, and, once you ‘had’ it, the ordinary struggle and suffering of being human would no longer be a problem. This image of enlightenment was based on the experiences of monks in Japanese Zen monasteries, and on the teachings from Suzuki’s mountain retreat, Zenshin-ji, which took Japanese monasticism as its model. The path to enlightenment, according to my adult informants, was a path of monastic seclusion and intensive practice.

Japanese Buddhism began in the 6th century, but Zen (originally known as ‘Chán’ in China) didn’t arrive in Japan for another 700 years. Unlike the earlier forms, which relied on strict rituals, historical teachings and doctrine, this new form of Buddhism placed greater emphasis on direct experience. In the Zen school, an unmediated experience of reality – and even enlightenment – was attainable through meditation, deemphasising conceptual thinking.

During the 13th century, these ideas began to flourish in Japan after two Japanese monks from the Tendai school of Buddhism, Eisai and Dōgen, travelled to China and were introduced to the teachings of the Chán school. When Eisai returned from China in 1202, he established a temple, Kennin-ji, in Kyoto, which became the central location for those hoping to study the new approach – it remains the oldest Zen temple in the city. A decade or two later, the monk Dōgen journeyed to China with Eisai’s successor, Myōzen. He returned to Japan transformed by his understanding of Chán and established Eihei-ji, a temple in the mountains of Fukui Prefecture, northeast from Kyoto. Working from memory of what he learned in China, he established the codes and forms of monastic conduct that are still followed to this day at Zen temples around the world, including Zenshin-ji, where my mother once practised.

Zazen is ideally performed while sitting with legs folded, facing the wall in absolute, upright stillness

At Zenshin-ji, these codes are followed during two periods of ango (‘peaceful abiding’) each year. Practitioners who attend ango adhere to a strict schedule (involving regular days, work days, and rest days) and engage in monthly retreats that generally last a week, known as sesshin (‘mind-gathering’). The schedule on regular days involves roughly four to five hours of meditation wrapped around an afternoon of intensive work. Sesshin days involve very little work but up to 12 hours of meditation. There are also three ceremonial services each day, regular Dharma talks (a formal lecture from a Buddhist teacher), and study time. Meals are eaten in the meditation hall in a style called ōryōki (‘the bowl that holds enough’), which is highly formalised and involves a great deal of ceremony. The overarching standards for conduct during ango emphasise silence and deliberate, harmonious interaction.

During ango, ‘meditation practice’ involves alternating periods of zazen (‘seated concentration’), which last from 30 minutes to an hour, and kinhin (‘walking back and forth’), a form of slow walking meditation that takes around 10 minutes and eases the strain from sitting. Zazen is ideally performed while sitting with legs folded in full or half-lotus posture facing the wall in absolute, upright stillness.

Serious Zen students might spend five years participating in the ango at Zenshin-ji. Some, seeking an even deeper engagement, might spend their entire lives in monastic practice.

I had other plans.

When I was first exposed to Zen, I was in my early teens and semi-feral. I went to school, of course, but on the weekends, I did everything I could to get away and get outside. The town of Mill Valley lies at the foot of the beautiful Mount Tamalpais, and many weekends were spent hiking and camping there with friends. Sometimes we went further afield, hitchhiking to camp on the beaches of Mendocino, 140 miles away. In summer, I took longer trips: climbing mountains, swimming in ice-cold nameless lakes, sleeping in alpine meadows.

A life of monastic seclusion and discipline didn’t appeal to me. And I couldn’t help noticing that the adults I knew who talked about Zen had lives that seemed at odds with their spiritual interests: they had spouses, houses, children, jobs, hobbies, extramarital affairs and addictions, among other things, all of which they would have to abandon if they were to follow the Way. None of them seemed to be willing to take the plunge. Zen didn’t appear compatible with modern life. So when my mother gave me a copy of Suzuki’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind (1970), hot off the press, I read it with genuine interest, but found it easy to put down. For the next 20 years, I hardly thought about Zen.

I attended a boarding school on the East Coast. I studied abstract algebra. I learned to play the electric guitar and graduated college with a major in music. Then I worked at a Burger King, then as a pot-washer, and finally as a mechanic.

Even when things were going well, I was unsatisfied with everything I did

I felt lost and sought advice from an old music professor, but he painted a bleak picture of life as a professional musician. He said I’d be better off moving to New York and playing in punk bands.

When I went to ask my mathematics professors what I should do, they were unanimous: ‘You foolish boy. Have you not heard of the digital computer?’ And so, I stumbled into a career in tech, eventually landing in Silicon Valley as a software engineer – a ‘hacker’ as we called ourselves at the time.

Living in San Francisco, I found time and energy to play music again. I started a band, the Loud Family, with a gifted singer-songwriter called Scott Miller. We even managed to make a few albums together and tour. And by my 30s, I had quit my job as a software engineer and dedicated myself to music

On paper, my life looked good. I had creative friends, gainful and enjoyable employment, and had even found a way to quit (or at least pause) my ‘day job’ – an opportunity most struggling musicians would kill for. But my experience of this life didn’t match how it looked on paper.

In my mid-30s, I was in the middle of a messy divorce (my second) and grieving the untimely death of my father from lung cancer. My problems were also internal. I was always wanting more of this and less of that. Even when things were going well, I was unsatisfied with everything I did and hyper-sensitive to criticism, especially when I made a real mistake, which I often did. This made me hard to work with. I often acted foolishly. I hurt people who deserved better from me.

Buddhism has always been a radical explanatory framework and a set of concrete practices that directly address the ‘human condition’. When we look closely, we find people everywhere grappling with the problem of being human. Across cultures and millennia, our species has returned time and again to the same fundamental question: Why do we make such a mess of things and how can we do better? The countless responses to this dilemma have given rise to a universal genre that attempts to explain (and solve) human folly.

At the start of Homer’s Odyssey, Zeus laments: ‘See now, how men lay blame upon us gods for what is after all nothing but their own folly.’ In the Dàodé jīng (Tao Te Ching) the Chinese sage Lǎozǐ spells out a similar concern:

When Dào is lost, there is goodness. When goodness is lost, there is kindness. When kindness is lost, there is justice. When justice is lost, there is ritual. Now ritual is the husk of faith and loyalty, the beginning of confusion. Knowledge of the future is only a flowery trapping of Dào. It is the beginning of folly.

Despite the murkiness of its early history, Buddhism crystallised around key axioms that offer different explanations and solutions for human folly. First, human suffering and misbehaviour are built in. They are intimately entangled with qualities that make us human: our capacity to use language, make long-term plans and form complex societies. Second, to use those capacities, we must construct a ‘self’. But this self is often based on flawed narratives shaped by culture and personal experience. Built on faulty assumptions, our self-stories generate desires – manufactured goals, preferences and ideals – which are driven by powerful emotions. But our experience of life often remains unsatisfactory, driving further striving and disappointment.

I was in the grip of the very human folly that Buddhism has always sought to address

Despite this predicament, the situation is not hopeless. The Buddhist ‘Way’ offers practical tools – ethical conduct, meditation, insight – that can transform our inner lives and outward behaviour.

By the time Buddhism evolved into the Chán schools in China (what would later be called ‘Zen’ in Japan), further axioms had been established. First, true learning occurs through relationships; second, awakening unfolds not just through studying texts, but from self-study mostly through zazen. When Zen eventually landed in the West with the arrival of Suzuki and others, these axioms began to find a new space to flourish.

Decades after first reading (and shelving) Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, I realised that I was in the grip of the very human folly that Buddhism has always sought to address. And so, in the middle of a busy and complicated life, I began an unexpected second career as a Zen practitioner.

Had I lived anywhere else in the world, this might not have been possible. The San Francisco Zen Center (SFZC), where I decided to practise, was unique for striving to make a monastic form of Zen accessible to laypeople.

I began with the kind of assumptions that are common among beginners. I thought that I would attain a persistent enlightened state through rigorous adherence to the traditional monastic model. I thought that through meditation I would resolve all my personal suffering, and that I would attain a deep understanding of human life. I believed this would change me, and might change those around me, too. I thought I could even become something like a sage, moving through life effortlessly on whatever path I chose.

And so, in the early 1990s, I began. Thankfully, because I was playing in rock bands for a living, I had a loose schedule, which enabled me to do a lot of sitting. I could also participate regularly in ango and sesshin at Hosshin-ji. I even did an ango sandwiched around a six-week international tour in support of the band’s second album, and got back in time to sit the seven-day sesshin at the end.

But after five years of this, it became clear that I needed a ‘real’ job. So I went back to working in tech. From that day on, and for many years after, my life was devoted to balancing the long hours and tight schedules in the tech sector with the long hours and strict schedules of Zen practice.

By the mid-2000s, I was growing more serious about Zen and wanted to become a teacher. But my life had become busier. I now had four children, spanning adulthood to toddlerhood. My wife and I were both working, and I was still playing in two bands.

The author, Anshi Zachary Smith, photo taken during the winter ango at Zenshin-ji. Courtesy the author

My teacher, Ryushin Paul Haller, suggested that I guide an ango at Hosshin-ji by serving as shuso (‘head seat’), a role that a monk must often take on, in order to pursue a career as a Zen teacher. Though I was unsure, I agreed mostly due to the Zen principle: when your teacher asks, you say ‘Yes’ without hesitation.

During the ango, I would rise at 3:30 am, ride my bike to Hosshin-ji with a brief stop for a donut and coffee on the way, change into my robes, run around the building with a bell to wake everyone up, have tea with Ryushin and his assistant, then open up the meditation hall for zazen at 5:25 am. After a couple of periods of zazen followed by a ceremonial service that involved a lot of vigorous bowing and chanting of the Zen liturgy, and finally breakfast, I would hop on my bike again, ride to the station and take the train to San Jose where I’d work a full day at my tech job. After that, I’d take the train back to San Francisco, ride home and arrive, often as late as 9 pm, to eat dinner alone at the kitchen table. I’d then fall into bed, sleep as much as I could and get up to do it again the next day.

I learned to become dedicated to, as Suzuki would say, making my ‘best effort in each moment’

It was exhausting and unsustainable – even with a supportive family. The monastic model favoured by SFZC and other institutions sets up social, financial and logistical barriers that are difficult for the majority of Zen aspirants to pass. Though my path was not typical, the Way is fundamentally the same. The most common mistake is to confuse the two.

A few weeks after my stint as shuso, Ryushin suggested that I start a zazenkai (Zen sitting group) – an informal, less-intensive kind of practice – at a community centre in my North Beach neighbourhood in San Francisco. I wanted it to be easy enough so that a participant could roll out of bed every weekday and attend a half-hour period of zazen. I kept the rituals basic: incense at a small altar, three bows at the start (accompanied by bells), a single bell at the end. Later, we added the chant used at SFZC temples after morning zazen. It begins by saying the following twice in Japanese:

Dai sai ge da pu ku

musō fuku den e

hi bu nyo rai kyo

kō do shoshu jo

And then once in English:

Great Robe of Liberation

Field far beyond Form and Emptiness

Wearing the Tathagata’s teaching

Saving all beings

The group is still going, roughly 15 years later, and it has taught me a lot in that time. I learned how to balance the intensive and the ordinary. I learned to become less concerned with what my practice should or could be, and more simply dedicated to, as Suzuki would say, making my ‘best effort in each moment’. I have learned to recognise, through intimate, ongoing self-study, the characteristics and processes involved in my own suffering and to open into the spaciousness that’s available in everyday life. This space has leavened and counterbalanced the emotions driving my habitual responses – my frustrations, fears, anxieties. Today, my experience of life is the fruit of simple, diligent practice.

In Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, Suzuki explains the process of becoming enlightened like this:

After you have practised for a while, you will realise that it is not possible to make rapid, extraordinary progress. Even though you try very hard, the progress you make is always little by little. It is not like going out in a shower in which you know when you get wet. In a fog, you do not know you are getting wet, but as you keep walking you get wet little by little.

To my surprise, this turned out to be true, even when my practice was just the simple act of sitting each day with minimum formality. I wasn’t alone. Though plenty of monks and nuns have spent their lives in monasteries, the monastic path was never considered the only way to go. In fact, from 618 to 907 during the Táng Dynasty (the so-called ‘golden age’ of Chán), laypeople were often held up as exemplary practitioners. One example is Layman Páng and his family. Páng is still celebrated for recognising that mindful attention to ordinary tasks can, over time, become a path to awakening:

How miraculous and wondrous,

Hauling water and carrying firewood!

Vimalakirti and the Doctrine of Nonduality (1308) by Wang Zhenpeng. Courtesy Met Museum, New York

In the Vimalakirti Sutra, written as early as the 3rd century, another layperson named Vimalakīrti is depicted as a house-holding family man and entrepreneur in the time of the Buddha. Even while lying sick in bed, Vimalakīrti manages to best Mañjuśrī, the Bodhisattva of transcendent wisdom, in a debate, while countless beings cram into his tiny house to watch.

They fiercely discourage the ‘pursuit’ of awakening or the idea of ‘learning’ how to be enlightened

In the end, I had to conclude that all the ideas I held about Zen practice when I started were wrong or, at the very least, misleading. There is no persistent state of enlightenment. The pursuit of such a state is vain by definition. There’s no ‘fix’ for the human condition in the sense that I originally sought. The Way is not accomplished by gaining ‘understanding’ in the conventional sense or by forcing the mind to shut up – no matter how appealing that prospect seems. These conclusions arose out of my own direct experience but also out of my reading of the Zen literature, which, for more than 1,000 years has been stating things differently.

The founding documents of the Chán schools in China and the Zen schools in Japan are a fistful of manifestos that point to the particulars of human experience and talk about how to practise with them. These are full of aspirational formulae and encouragement, but, at the same time, fiercely discourage the ‘pursuit’ of awakening or the idea of ‘learning’ how to be enlightened. Instead – at the risk of oversimplifying something that’s bafflingly complex – they describe two major modes of engagement that characterise Zen practice.

The first of these modes has been called ‘conventional cognition’ and is a form of thinking that is deeply familiar to most humans. This mode continuously manifests in our conscious and semi-conscious minds, engaging the human qualities of language, planning and sociality. It can appear as a kind of ruminative self-narration underpinned by emotional tags that drive both inner life and outward behaviour. We experience it as a running dialogue in our heads, which expresses our hopes, fears, experiences, desires, uncertainties. This mode works by building models (of the world and self) using a vast storehouse of remembered, language-ready categories to imagine future outcomes. These models allow us to navigate the world through anticipatory action. As we move through our day, we imagine how others will perceive us, recalling past events to anticipate their responses and determine what we should say and do.

Conventional cognition gets a bad rap in most Buddhist literature because it’s so obviously the cause of the aforementioned human folly and suffering. How could it be otherwise? We are beings with a very limited perspective, provided by our sensory hardware and the experiences in our relatively short lives, operating in a world of ungraspable complexity. We are almost constantly focused on what we think will benefit us, even though our ungraspable world is so richly interconnected that the effects of our actions fall far beyond our understanding or control: determining which factors will genuinely do us good is very hard to figure out. What could possibly go wrong?

But this same mode is directly responsible, at least in part, for all the beautiful things that humans make and do. Poetry, iPhones, quantum mechanics, Buddhism – none of these would exist without conventional cognition. Furthermore, we literally can’t live without it. The idea that we can somehow exit this mode for any appreciable length of time is absurd. The great Táng Dynasty Chán master Zhàozhōu captured this admirably when he said: ‘The Way is easy. Just avoid choosing.’ He then added, ‘but as soon as you use words, you’re saying, “This is choosing,” or “This is clarity.” This old monk can’t stay in clarity. Do you still hold on to anything or not?’ (My translation.)

The other mode posited in Buddhist literature goes by many names, but Suzuki dubs it ‘big mind’. In contrast to the narrow focus of conventional cognition, big mind manifests as a kind of broad, relaxed, receptive attention that, by default, easily gives way to focused attention when circumstances demand it. It is not particularly tied to language. The categories, objects and concepts that are the province of conventional cognition – the elements directly involved in the activities of self-construction and self-narration – have no meaning for big mind. Conventional cognition is driven by powerful emotions; big mind is driven by an appreciation for the simple act of being alive.

While both modes are active and ever-present, many people are barely aware of the presence of big mind because their preoccupation with conventional cognition is so strong. One can easily observe this through zazen. Sitting to meditate, we can experience the feeling of being tangled up in thought, which can stop us being aware of ourselves as embodied beings sitting upright. Just paying attention to our breathing can be a struggle as thoughts intrude. The point of a sitting practice is to wholeheartedly study, as intimately as possible, the moment-to-moment activity of your body and mind until big mind swims into view, even briefly. From there, the tangled relationship between these two modes becomes clearer, and big mind begins to take its natural place in our everyday lives – not only while sitting zazen, but also while walking, talking, working and playing. This is an answer to Zhàozhōu’s question: do you still hold on to anything or not? A new relationship between big mind and conventional cognition is what we preserve: a continuous practice of staying awake to our activity and its consequences in the context of big mind.

One might reasonably ask: ‘Well, what good is that?’ It’s an excellent question and the answer has two parts.

First, on a practical level, when we meet the world through big mind, even imperfectly, the grip of conventional cognition is loosened. This doesn’t mean our habitual responses disappear. On the contrary, they sometimes become more visible. But they are now surrounded by a sense of space and choice. We’re no longer compelled to act on our habitual responses, and it becomes easier to consider more skilful alternatives. We find ourselves entering each moment with a new awareness as our sensory experience of the world outside meets the inner world of our concepts and habits, and through that meeting – infused with a kind of compassionate curiosity – a way forward takes shape seemingly of its own accord. After we act, we see the results, and then begin the cycle again in a way that feels more agile and spontaneous.

The ceremonies move the rock of practice nearer to the centre of the river of the ordinand’s life

Second, beyond its practical benefits, this practice opens us to experiences that go far beyond what we think of as ‘the everyday’. It underscores what many historical traditions have observed: the full range of human experience is much broader than we normally expect.

I have been practising in this way for roughly 35 years. Some of this practice was intensely monastic and formal. In that time, I passed through three successive ordination ceremonies – lay ordination, priest ordination, and Dharma transmission – with my teacher Ryushin. Each of these involved long periods of preparation, a lot of it spent sewing together a robe in the same way that monks have done for thousands of years. The ceremonies themselves, especially the Dharma transmission, which takes weeks to perform, are designed to change the life of the ordinand by moving the rock of practice nearer to the centre of the river of their life. After each ordination, I felt suddenly and startlingly different, and the vow to take full responsibility going forward for my conduct and its consequences gathered weight.

But, more often, I practised in the context of a busy life involving work, family and passions (for me, art-making and long-distance cycling). And, over the decades, the reward of continuous practice – as emphasised by Dōgen Zenji, Suzuki and countless other teachers through the centuries – has become more deeply embedded in my being. It has manifested in my day-to-day life. As usual, this change has been both sudden and gradual.

The author’s rakusu (one of the garments given during ordination) showing his own stitches stacked against a naturally occurring pattern in a found leaf. Photo supplied by the author

So, what are we to do? How are those of us still caught in the flux of the ‘modern’ world supposed to find peace, alleviate suffering, and confront human folly? My own experience might suggest a deprecation of monasticism, but this would be inaccurate. Monastic practice, tuned as it has been for thousands of years, is an excellent vehicle for exactly this exploration. A person who completely gives themselves over to the forms and schedules prepared for them is constantly being reminded of the beauty and the burden of conventional cognition. Again and again, they are given the opportunity to lay down their burden. Initially, they may not even recognise this invitation. Later, they might ignore or resist it, clinging to ideas they’ve developed about how things ought to be. But, in the long run, at least some practitioners are able to loosen their grip.

That said, of the few people who are financially and logistically able to take advantage of extended monastic practice, fewer still are able to follow those forms and schedules completely. Age, fitness, physical incompatibility, disability and other constraints often limit participation in traditional monastic practices. Fortunately, the heart of zazen has nothing to do with where you live, whether you can twist your legs into lotus posture or whether you like getting up at 3:30 am.

Simply taking up the posture of zazen in a quiet room has a powerful effect on body and mind. To do it, find a quiet place and, in that place, find a posture that will allow you to keep physically still for 30 minutes or so. If that is difficult or you can’t sit comfortably for 30 minutes, standing or lying down is also an option.

What does it feel like to be present? What does it feel like to be ‘non-present’?

Zazen is essentially a yogic practice, which invites a particular kind of continuous engagement, especially with the body and breath but also with the mind and senses. The posture, both inner and outer, should feel simultaneously relaxed and energised.

A helpful principle is ‘always be sitting’. This doesn’t mean one must literally sit – those standing or lying down are free to construe ‘sitting’ metaphorically. ‘Always be sitting’ means that whenever one is engaged in zazen, one should, as much of the time as possible, be bodily engaged. This means forming the sitting posture as if it were happening for the very first time, feeling the actual rate and depth of the breath, bringing attention to where discomfort arises and, perhaps, moving gently and deliberately to relieve it.

This kind of attention isn’t always easy. Sometimes we’re able to be present and sometimes we’re not. Such unpredictability is often a source of struggle for Zen students because they think they’re supposed to be ‘quieting the mind’ and they see the moments when they’re not as a failure. But this is fundamentally incorrect and unhelpful.

The real invitation in zazen is not to suppress thinking, but to participate fully in, and become intimately aware of, our own version of the attentional cycle. Is it short or long? What does it feel like to be present? What does it feel like to be ‘non-present’?

This last question is important. In the early stages of practice, when the mind is fully engaged in conventional cognition – especially when emotionally charged thoughts and stories are present in the mind – the broader view afforded by big mind is obscured. And the transition between these states, which can happen repeatedly during a single sitting, is extraordinarily subtle. One moment you can be sitting in awareness, and the next you’re simply thinking about your day – remembering a conversation or anxiously anticipating something – without knowing how you got there.

This can get complicated. Consider the story of a monk I practised with at Zenshin-ji, who told me she once walked in the garden and was utterly transfixed by the sight of a blooming flower. Its beauty, perfection and aliveness stopped her in her tracks and, as she paused there to take it in, she was moved to tears. But then, some seconds later, a thought arose: ‘And… she was moved to tears!’ She heard this phrase in her mind, and the tone of the thought had such a sneering, mocking intonation that she immediately reacted angrily, raging at herself for spoiling the immediacy of the moment by commenting on and distancing herself from the experience. In the end, the relationship between big mind and conventional cognition is a tangled weave: as our attentiveness is erased, we can go from unconditioned appreciation to self-condemnation in a flash.

Daily practice can feel like walking in a fog and slowly being ‘dampened’ by the effects

On the other hand, the transition back into big mind doesn’t involve this erasure. When we return, we are still intimately (or at least retrospectively) aware of the thoughts, emotions and texture of whatever episode we’re right in the middle of. And in this return lies the heart of zazen: the possibility of making a subtle, almost imperceptible effort to broaden and settle our attention, to fully inhabit the moment, and to be completely present for what comes next.

Once a routine is established, a regular dip into more intensive practice can be tremendously helpful. Though daily practice can feel like walking in a fog and slowly being ‘dampened’ by the effects, more intensive practice offers something different. Even devoting a single day can allow the mind to settle more deeply, freed temporarily from our regular preoccupations. Such moments can offer surprising clarity. Perhaps the corresponding metaphor is more like a long swim in a mountain lake or, if you prefer, a quiet forest pool.

Finally, it’s crucial to have companions on the Way. Practising zazen in the company of others provides powerful support and shared commitments. Comparing experiences and testing insights with others can be an antidote to the blindspots and subtle delusions that plague us all. Sustained collective practice also helps cultivate samadhi – the deep meditative absorption that clarifies perception and steadies the mind. That’s why, in Buddhism, the ‘three treasures’ are Buddha (the historical figure and the symbol of the potential for awakening), Dharma (the teachings), and Sangha (the community).

Dōgen Zenji, the remarkable person who really established the Zen school in Japan during the early 13th century, wrote a manifesto called Fukanzazengi, a title that may be translated (very loosely) as ‘Everyone should be sitting zazen like this.’ The last few lines, in the translation used by SFZC, read:

Gain accord with the enlightenment of the Buddhas; succeed to the legitimate lineage of the ancestors’ samadhi. Constantly perform in such a manner and you are assured of being a person such as they. Your treasure-store will open of itself, and you will use it at will.

In the 1960s, after Zen had travelled from Japan to San Francisco, many Americans embraced this imported spiritual practice with a hopeful, if often misguided, belief: enlightenment – the ultimate fix for the human condition – demanded monastic discipline and withdrawal from the clatter of modern life. To find a cure for human folly, one had to step outside the world entirely. I carried the same conviction.

A view towards the mountains from the Tassajara Zen Mountain Centre in California. Photo supplied by the author

When I look back at the person who began practising Zen in earnest more than 30 years ago, I can see that my initial ideas about Zen were misguided. As those ideas began to slowly unravel, the texture and quality of my life has been transformed. It has become richer, more vivid, and more deeply alive than I could ever have imagined.

I’ve come to understand that the Way isn’t a destination located far from the world, reached only by force of will or sudden insight. It unfolds through steady, daily practice. What Zen offers is quiet, strange and radical: a form of engagement that begins almost imperceptibly but can grow into something truly transformative.

As Suzuki put it, if you walk through fog long enough, you’ll eventually be soaked. Slowly, you begin to inhabit the texture of your own life more completely. Eventually, you stop trying to be elsewhere. You begin to realise the Way was never hidden up a mountain. It’s right here, buried far beneath your own ideas about who you should be.