The Zen master hit my hand and asked: ‘Where did the sound go?’ I had no idea. Meeting Zen masters in South Korea was fraught with the risk of appearing a little stupid but I did not mind. It was also fun, like playing the young student Grasshopper in an episode of Kung Fu, or meeting Yoda, the grandmaster of the Jedi council.

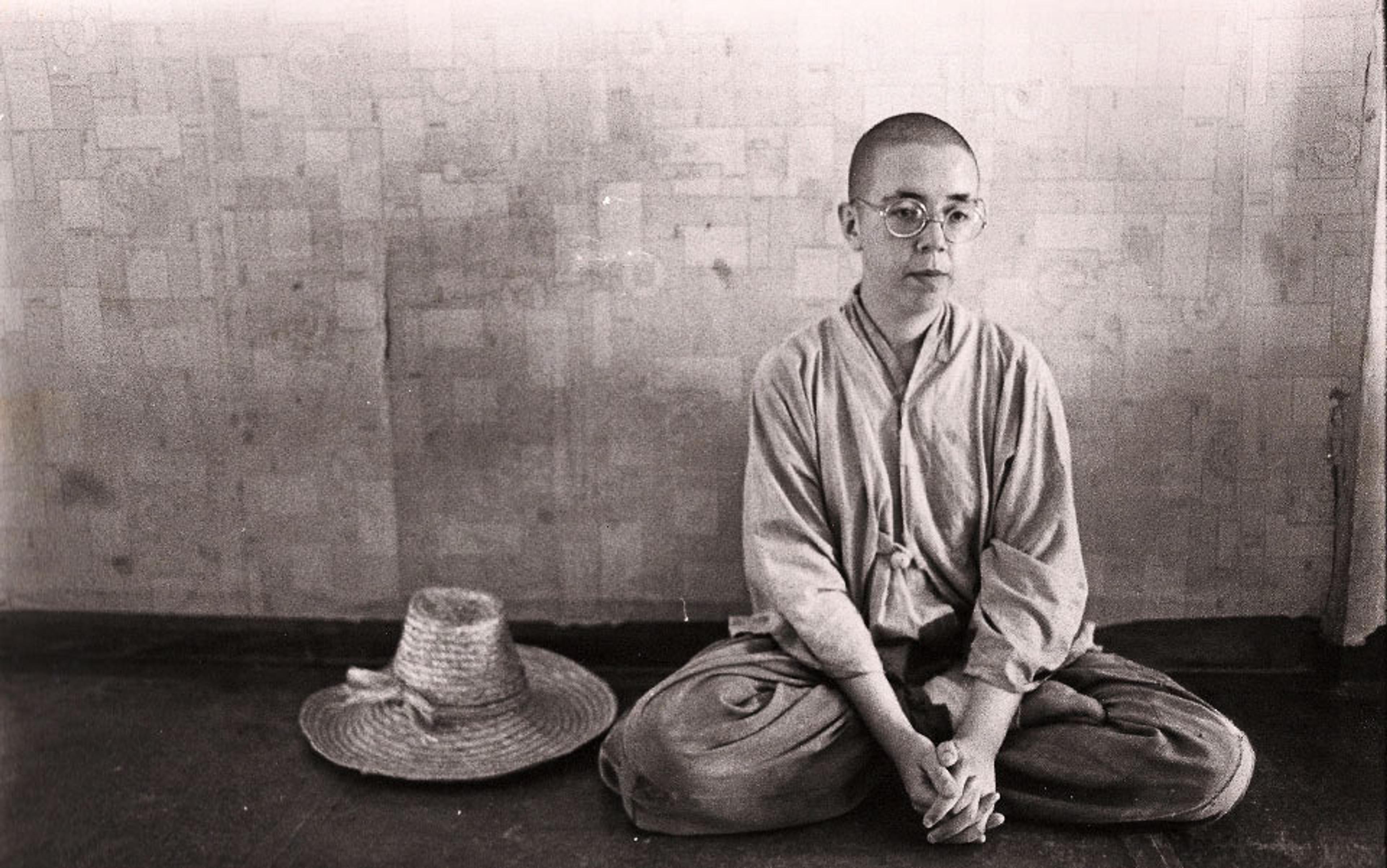

It was in South Korea in 1975 that I decided to become a Zen nun. I had wanted to see if meditation would enable me to change my mind. I’d been idealistic from a very young age: from 11 onwards, I’d wanted to save the world. I became an anarchist and read Bakunin; then I dreamed of taking the Magic Bus to India from rural France. But at the ancient age of 18, I realised it wasn’t that easy to change the world, let alone myself. So when I read a Buddhist text that suggested meditation might help, I decided to find a teacher and a practice. I ended up in a Zen Buddhist monastery in South Korea where, for 10 hours a day, I silently asked the question: ‘What is this?’

The Zen word ‘koan’ is sometimes used in common parlance — as in ‘What is the koan of my life?‘ Or ‘Is this is a koan for me?’ The hero of Ben Lerner’s novel Leaving the Atocha Station (2011) realises that his lack of Spanish enables him to speak in ‘enigmatic koans’. At the University of Warwick, there is a six metre-high sculpture called the White Koan by Lilian Lijn, which rotates and is illuminated by fluorescent lights. On MTV, Skrillex, the American electronic musician, recently introduced a DJ duo from Bristol who call themselves Koan Sound after their unusual bass sound. And in June this year, the Marketwatch.com columnist Paul B Farrell wrote an article headlined ‘The ultimate Zen Koan? Your retirement’. They all used the word ‘koan’ to signify, among a multitude of ideas, a question, a mystery, a concern, an enigma, a riddle, something strange.

‘What is this?’ is one of the most popular koans used in Korea. It is not a riddle with a definite answer. Traditionally, it is seen as a method of radical questioning that will enable one to see one’s true nature and thus become a Buddha. But it is not as easy as that: it takes more than just a weekend meditation intensive to attain the way. It requires years and years of sitting on a cushion and asking until you develop a sensation of questioning so powerful that it ‘explodes’, as the tradition says. In Korean Zen, they say that to accomplish this you need to have great faith, great courage and great questioning. However, I was not so interested in slowly awakening to my own true nature: I wouldn’t have minded if it had suddenly and unexpectedly happened to me. I wanted all along to cultivate wisdom and compassion and, more than anything else, dissolve my restrictive and painful habits of mind and heart.

In the mid-1970s, from the age of 18 to 22, I lived between France and England. For the sake of my parents, I tried to go to university twice. However, after three months of study, I left the department of English language in Reims because student life seemed too restrictive and bland. At my next attempt, I lasted the three hours of the first lecture in the department of political sciences at Grenoble.

My rebellious tendencies could not accommodate French business practices either, so I abandoned working in France, and decided to try my luck in England. I managed to find ‘temp’ jobs as a canteen assistant. But, as a vegetarian, I was defeated by a bread pudding made of suet. In the end, I found myself working for the Law Society and spent four years living in squats with a diverse population of misfits. All they seemed to have in common was listening to Van Morrison’s Moondance album on turntables with a groove problem. Uncannily, they always seemed to get stuck on the track ‘Into the Mystic’. Although I seemed to be free in this period of my life, I felt as stuck in the grooves of my mind as that record player — the grooves of jealousy, despondency and confusion.

In order to find a spiritual solution, I went to any Eastern events happening in London at the time. None seemed to fit: Guru Maharaji — a little too high on his throne; Sufism — a bit too much praying on knees; Rajneesh — too much hyperventilation; Tibetan lamas — too medieval. It was not easy. As a third-century Zen patriarch said: ‘The great way is not difficult for those who do not pick and choose’. So finally I set off for Asia.

After a few months wandering in India and Thailand, I arrived at the monastery of Songgwangsa in South Korea. At the time, this was the only temple in the country that accepted foreigners. I showed up while the largest ceremony of the year was taking place. So I went to help in the kitchen, washing vegetables. During a break, a Korean laywoman asked me about my life. When she realised that I had no ties — no work, no husband, no children, no study — she was delighted for me. If she were me, she said, she would become a Zen nun. I pondered this for a while. She’s right, I thought. Why not stay here for a year or two, and do something totally different? Maybe in this place and tradition I could find a way to stop repeating the same painful mistakes. So, as is customary for meditation monks and nuns in Korea, twice a year, in winter and in summer, for three months at a time, I started to ask ‘What is this?’ for 10 hours a day. Rather than experience the ‘whizz bang’ of enlightenment, I simply found that a greater awareness and compassion were growing within me. This is why I ended up staying in Korea for 10 years.

I came to see that meditation was not about suddenly lighting up like a Christmas tree

Two things happened early on, which convinced me that this was all worthwhile. A month into my second three-month retreat, I was sitting on my cushion asking ‘What is this?’ when I suddenly became very aware of what was going on in my mind. It was all about me being at the centre of the universe — what I wanted, what I hoped for, what I did not like, and so on. At the time, I was practising with four other young women, and I realised that they too were doing exactly the same thing. Self-interest was the basis of our identity. This clear awareness did not make me sad or upset. Instead, I found it funny. It exposed my fundamental mis-perception of myself as an incredibly compassionate and selfless person. This experiential awareness led to a deep self-acceptance. I saw clearly for the first time the obstacle at the centre of my suffering and what was needed to transform it. This made me feel lighter. I wasn’t in the dark any more about the conditions that had caused me to keep making the same mistakes again and again.

The second thing happened a few months later. This was during the ‘free season’, when instead of meditating one could travel about in Korea and take care of errands in town. I went to a bank to change some money. The bank teller made an error and gave me more than I should have received. My first thought was to take the money as it would be one against the capitalist system — and more for me, of course. But I stood still, unable to move. I could not do it, could not take the loot. I gave the excess money back. I did not want the bank teller to get into trouble for his error. I was so surprised that I had not reacted in my old habitual way. It had not felt like an intellectual or rational act — forcing myself to do something out of high-minded Zen idealism — but an experiential one. Something seemed to have arisen unbidden as a spontaneous response to the situation.

I came to see that meditation was not about suddenly lighting up like a Christmas tree, but about releasing something and letting go. It became clear that meditation functioned in a subtle subterranean way. At the time, I could not have explained how or why. It was only after I left the monastic life and encountered Buddhist vipassana meditation that I understood how this process worked.

I left Korea when my main Zen teacher, Master Kusan, died, and I met my future husband. We went to live in England in a Buddhist community where most of the members practised vipassana meditation. This practice consists in cultivating awareness by focusing on the breath, the body, on thoughts or sounds. I was curious to try this form of meditation and did a number of seven-day silent retreats as a layperson taught by other laypeople. It was a very secular context, in sharp contrast to my monastic experience in Asia.

I discovered that although it was a different technique from the Zen questioning, we were actually developing the same things: concentration and experiential inquiry. I realised that the particular meditation technique we used did not matter so much as cultivating these two qualities together, which helped one develop calm and clarity. And this was also my Korean Zen teacher’s leitmotif — cultivate calm and brightness together. This, I believe, is why meditation works for so many people and has become so popular: it does indeed make us calmer and clearer, more stable and open. More than that, it enables us to creatively engage with life instead of grasping at and fixating on things that not only limit us but are painful.

So how do we meditate? We can either ask a question or koan (without looking for an answer), or focus on the breath or listen to sounds. The first part of the exercise is to concentrate. But this is not the kind of concentration expected from us at school, where we are told to tense up and narrow our attention. In meditation we use the object simply as an anchor or a point of reference, to which we can keep coming back. We are not trying to stop the thoughts, but to be less caught up in them, able to make the choice to return to the anchor. Every time we do this, we refrain from feeding our mental habits. This is why we often feel more spacious and lighter when we meditate. It is also why we can start to take our thoughts less seriously as being ‘ours’. Instead we see that a thought is just an idea that has arisen. We can then ask ourselves: ‘Do I need to continue to think it or not?’ We do not reject our mental processes, but allow them to resume their creative functions of imagining, reflecting or planning as needed at that moment.

The second quality we seek to develop in meditation is experiential enquiry. We can do this either by directly questioning our experience, as in asking ‘What is this?’, or by simply observing that moods fluctuate, sounds are conditioned by various circumstances and physical sensations can be fluid, morphing into something else or disappearing. Our impressions are totally impermanent, unreliable and conditioned. This challenges the tendency we have to pin things down, and to feel trapped in thoughts such as ‘It is always like this’ or ‘It will always be like that.’ Over time, we realise that our thoughts, feelings, sensations, as well as the conditions around us, have a tendency to change, and this can be liberating. It makes a big difference when we ask ‘How long is this going to last?’ with curiosity and interest. If it is only the time between the changing of a traffic light, it does not matter. But if a feeling lasts a day or two, can we address the situation with wisdom and compassion?

The Buddha was a pragmatist and a good psychologist. So although certain Buddhist religious beliefs might not fit so well with the modern scientific world, meditation does

But there is no one thing called ‘Buddhism’. The various types of Buddhist meditation have evolved and developed over time in diverse religious contexts while adapting to different cultures and ideologies. When Buddhism went from India to China in the first century CE, it made a big leap from a mythological and philosophical tradition to a far more pragmatic and historically conscious one. In the same way, when Buddhist meditation enters the modern world, be it in Europe, the Americas, or Australasia, it finds itself speaking to another culture and time. It encounters a world with a strong psychological and scientific frame of mind, rooted in liberal and democratic ideals. Ours is also a pluralistic world where different kinds of Buddhism are meeting and vying with each other at close quarters, often for the very first time.

The Buddha was a pragmatist and a good psychologist. So although certain Buddhist religious beliefs might not fit so well with the modern scientific world, meditation does. It deals with the mind, body and emotions and the ways in which events arise, and then pass away. This might explain why many therapists have become interested in meditation. In 2000, I attended a conference on Buddhism and psychotherapy in Sydney, Australia. I was surprised to find that meditation was practiced and developed for therapeutic purposes by many different types of psychotherapists: from cognitive behavioral therapy to Hakomi, existential, and dialectical, among others.

At the same time I learnt that Buddhists were creating new therapeutic techniques inspired by meditation, such as core process therapy or mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Some of these therapies are more Buddhist and some more secular. It seems that there must be a great difference between sitting on a cushion for many hours in a monastery and spending an hour a week with a Buddhist therapist. But the criteria should be: does it work? And by ‘working’ I mean: does it relieve suffering and help the person to be wiser and more compassionate? It seems that some of these approaches do, although whether this is the same thing as a spiritual practice is another question.

At the heart of Buddhist meditation is the awareness that we have some problems, and that something can be done about them. We can feel stuck when we repeat the same mistakes again and again. Sometime we might feel confused or in the dark, or that we have great potential but do not seem able to access it. One of the aims of spiritual practice is to embrace suffering, understand its root causes and try to either dissolve them or to work with them in a creative way. Traditionally, one does this by means of a threefold training in ethics, meditation and wisdom — meditation is but one part of this process. For some, this might involve certain forms of psychotherapy, too. Even so, I do not believe that meditation and psychotherapy are the same. They can certainly complement each other, but they also perform specific tasks in different circumstances.

As I started to teach meditation and encounter people privately, I felt I needed some interpersonal training. So I did a counselling course. This was revelatory. It showed me clearly that in dealing with people, meditation experiences were not enough. I needed to cultivate and develop listening skills, and learn how to ask questions and to make suggestions. I have continued this training by myself, and have read many books about, for example, people’s experiences with depression, so that I can know more about what they might be experiencing and be more empathetic.

Meditation is self-driven; it all depends on one’s own effort, dedication and interest. Nobody can do it for you. (This does not mean, of course, that a teacher is unnecessary or that there is no value in meditating with other committed people.) Therapeutic work, by contrast, requires another person. A great deal of its transformative power comes from this interaction. In terms of experiential enquiry, the psychological method at times can be similar to that of meditation, particularly if one is exploring what is happening in the present moment or if one is looking deeply at the impermanence or conditionality of the past. The one major difference I would see between the two approaches is the role of concentration, which is not generally emphasised in the therapeutic context. However, in the therapy called ‘Focussing’, elements of concentrative meditation are used in an entirely non-Buddhist context.

The questioning helps with the energy and the directness. And the listening, for example, anchors it in a wide-open experiential space

Today, there is a great deal of interest in the use of mindfulness as a therapeutic tool. Pioneered in 1979 by Jon Kabat-Zinn, who founded the Centre for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society at the University of Massachusetts, mindfulness combines elements of Buddhist awareness meditation with yoga exercises and various medical therapeutic techniques. Recently, I was sent an article written by a teacher of acceptance and commitment therapy (in which mindfulness plays a central role) who maintained that it was not even necessary to meditate in order to experience the benefits of mindfulness. We are now in a situation where there is a large spectrum of possibilities in using meditation and mindfulness, from a strictly traditional approach, all the way to therapeutic techniques based on a sprinkling of Buddhist ideas.

This isn’t altogether out of tune with the Buddha and his emphasis on experiencing mindfulness and meditation techniques for yourself. One of his key injunctions was: ‘Come and have a look: see for yourself if it is working or not.’ As he stated in the Kalama Sutta:

Don’t go by reports, by legends, by traditions, by scripture, by logical conjecture, by inference, by analogies, by agreement through pondering views, by probability, or by the thought ‘This contemplative is our teacher.’ When you know for yourselves that ‘These qualities are skillful; these qualities are blameless; these qualities are praised by the wise; these qualities, when adopted & carried out, lead to welfare & to happiness’ — then you should enter & remain in them.

What does the practitioner of meditation — whether Buddhist or not — regard as the aim of his or her meditation? Is it to be enlightened? Is it to relieve suffering and dissolve its causes? Is it to be released from all greed, hatred and confusion? Is it to know emptiness from the inside? Is it to become nobody? Is it to experience an oceanic feeling? Is it to have such equanimity that you feel above all conditions?

Personally, I would see the aim of meditation as helping us to embrace and understand suffering, its causes and conditions, in order to enable us to develop our potential for stability, balance, joy, appreciation, love — and compassion for all those whose lives we depend upon and with whom we share the world. It is not just about an internal transformation. It also needs to affect the way we relate to and behave in the world. As the Japanese Zen Master Dogen said in his work the Genjokoan:

To study the Buddha’s way is to study oneself,

To study oneself is to forget oneself,

To forget oneself is to be enlightened by all things.

In 1992, I went back to Asia to research a book on Buddhist women, their lives and their practices. I interviewed 40 women from Asia and the West, nuns and laywomen from many different Buddhist traditions. Some of these traditions are sometimes frowned upon as not being meditative enough. But what struck me was that it did not matter what traditions they came from and what techniques they used. What was essential was these women’s sincerity and dedication. From then on, I trusted myself and my practice as never before. Nowadays, I combine Zen questioning with awareness techniques, and they complement each other well. The questioning helps with the energy and the directness. And the listening, for example, anchors it in a wide-open experiential space.

When I teach, my aim is to support people in uncovering and trusting their own wisdom. This is why I am a multi-choice teacher. On a seven-day retreat, I will suggest a different theme each day, as well as several ways to try to cultivate that theme in meditation. This is so that people who come with different tendencies and circumstances can find something that works for them, something that relieves some of their suffering and develops their potential for wisdom and compassion. Moreover, I am fortunate to be a teacher, as I learn so much from the people who attend my meditation courses — how they understand, what works, what doesn’t. It is a mutual process. They are in a constant evolution, and I am too.