On 22 January 1817, Henri Beyle’s heart was beating fast. Not because he had braved the robber-infested road from Bologna, but because he was now approaching the city of Florence. Glimpsing ‘like some darkling mass’ the monumental dome, conceived by Filippo Brunelleschi, sitting atop the Santa Maria del Fiore, this first sight of the Tuscan city dazzled him. ‘Behold the home of Dante, of Michelangelo, of Leonardo da Vinci,’ the 30-something Frenchman thought to himself. ‘Behold then this noble city, the queen of medieval Europe! Here, within these walls, the civilisation of mankind was born anew.’ Overwhelmed by the historical associations evoked by the city, Beyle later wrote in a travelogue:

I found myself grown incapable of rational thought, but rather surrendered to the sweet turbulence of fancy, as in the presence of some beloved object. Upon approaching the San-Gallo gate, with its unbeautiful Triumphal Arch, I could gladly have embraced the first inhabitants of Florence whom I encountered.

– from Rome, Naples, and Florence (1817), translated by Richard N Coe (1959)

Perhaps this emotional turbulence helps to explain the odd event that occurred soon after. Once Beyle passed through the city gates, he left his carriage and plunged into Florence. Though he had never set foot in the city before that day, he had studied maps with such intensity that he had internalised them. Without a local guide or a moment’s hesitation, Beyle made his way to the Basilica di Santa Croce. The city’s largest Franciscan church, the Santa Croce boasted stunning works of art, including Giotto’s fresco The Coronation of the Virgin with Angels and Saints, as well as funerary monuments to celebrated residents of Florence, including Dante, Galileo, Machiavelli and Michelangelo.

The Coronation of the Virgin with Angels and Saints (Baroncelli Polyptych) (after 1328) by Giotto. Courtesy Santa Croce Opera

But rather than seek out the Giotto, Beyle instead wandered through the ‘mystic dimness’ that filled the church and asked an obliging friar to open a locked chapel. On its ceiling was (and remains) a fresco of sybils by Baldassare Franceschini, a relatively obscure late-Baroque painter better known as Il Volterrano. Sitting down on a stool, Beyle leaned back and rested his head on a desk behind him, gazing at the sybils floating above him. There soon followed, he later recalled:

the profoundest experience of ecstasy that, as far as I am aware, I ever encountered through the painter’s art. My soul, affected by the very notion of being in Florence, and by the proximity of those great men whose tombs I had just beheld, was already in a state of trance.

Coronation of the Virgin (1653-61) by Il Volterrano, in the Niccolini Chapel in the north transept of the Basilica of Santa Croce. Courtesy Santa Croce Opera

Beyle does not say how long he stared up at the fresco, but it was long enough to reach ‘that supreme degree of sensibility where the divine intimations of art merge with the impassioned sensuality of emotion.’ Upon leaving the church, he wrote: ‘I was seized with a fierce palpitation of the heart …; the well-spring of life was dried up within me, and I walked in constant fear of falling to the ground.’

That swoon swept into existence le syndrome de Stendhal – ‘Stendhal’ being the nom de plume used by Beyle for nearly all his published works, including the novels The Red and the Black (1830) and The Charterhouse of Parma (1839). Though yet to be listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5, 2013), the syndrome nevertheless seems to be real. Every year, a few dozen tourists to Florence are rushed to the local hospitals, literally overcome by the city’s array of paintings, sculptures, frescoes and architecture. Some lose their bearings, others lose their consciousness, yet others still, on rare occasions, nearly lose their lives. In 2018, a heart attack befell an Italian tourist, Carlo Olmastroni, as he gazed at Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus in the Uffizi. (His life was saved by four other tourists, all doctors, who had also been standing and staring, slack-jawed, at the Botticelli.)

The Birth of Venus (c1484-6) by Sandro Botticelli. Courtesy Uffizi Gallery, Florence/Wikipedia

According to Graziella Magherini, the psychologist who in 1989 coined the term ‘the Stendhal syndrome’, dehydration and dense crowds certainly played a role in these tourists having heart palpitations and hallucinations. Yet in an interview in 2019, she insisted on another factor: ‘The psychological impact of a great masterpiece.’ Even scientists who dismiss the syndrome as psychosomatic confess that art can have this impact, though they refuse to diagnose it as a psychiatric disorder. A few years ago, another Florentine psychologist, Cristina di Loreto, noted in a BBC interview: ‘when you’re observing a piece of art, there are specific brain areas that are activated.’

Most museum visitors spend 15 to 30 seconds in front of a painting before they move on to the next one

Nevertheless, I am drawn to Magherini’s diagnosis. I confess, however, that these parts of my brain seem immune to this special power, not just of Renaissance art, but nearly all art within museums. When I go to these hallowed institutions, I go mostly through a sense of duty. This is what I do to renew my credentials as a man of culture. Or, more often, this is what I do when I serve as a tour guide. Over the years, I have taken my students to the Louvre and the Pompidou in Paris, and I have taken visiting friends and family to the Menil Collection and the Museum of Fine Arts, both in Houston; in New York, I have taken my children to the Metropolitan and to the Museum of Modern Art. Once I enter a museum, I stroll along the galleries, hands clasped behind my back as I scan the walls. When I do stop in front of a painting, I almost always turn to the information plaque next to it before the painting itself, spending more time reading the description than I do gazing at the painting. It is as if I am more intent on framing its place in history than I am on the painting inside the frame. And I look at other visitors as they look at the paintings, wearing ear buds or holding a guidebook, and photographing the works and, just as often, themselves in front of them. Are they, I wonder, more or less serious than I am?

Well, I suspect they are what passes for serious nowadays. Repeated studies reveal that most museum visitors spend an average of 15 to 30 seconds in front of a painting before they move on to the next one. Museums have become obstacle courses where contestants vie with one another to be the first to reach the gift shop, replete with reproductions of what we had trudged past moments earlier as we stumble across the finish line of this numbing marathon of high-mindedness.

But here is the rub: the way we visit museums today is somehow both totally normal and deeply abnormal. On the one hand, most everything we do in the age of Facebook, iPhone and multitasking feels faster and thinner, while museums seem vaster and thicker. How many of us would be truly shocked to enter a museum one day and discover there the same moving walkways as carry our bodies and bags at airports? On the other hand, the ostensible reason we visit museums – to find enjoyment and perhaps enlightenment in works of art – seems increasingly quaint. Researchers attribute this breathless pace to the nature of modern tourism: we ‘do’ the great sites of history and art less to see them than to be seen by them, more to add to our cultural capital than to our personal growth. This is why most photos I receive from family, friends and students who are travelling abroad are selfies in front of iconic works of art or architecture.

While I rarely take selfies, I always send postcards. But I need to remind myself that this doesn’t make me any more cultured or sophisticated than the tourists wielding smartphones. Selfies and postcards channel the same message: I was there. As to what I saw there, while one image is reproduced on the card’s front side, on its reverse I also provide a verbal list of other works I saw: Picasso and Pissarro, Van Gogh and Vermeer, David and Delacroix, ticking them off one by one. But what, precisely, do I mean by ‘saw’? Nothing more, really, than that I was close enough to these works to take a selfie. How odd. As the psychologist James Pawelski told The New York Times in 2014: ‘When you go to the library, you don’t walk along the shelves looking at the spines of books and on your way out tweet to friends, “I read 100 books today!’’’

None of this would have shocked Stendhal. The business of cultural tourism was already well on its way to this, with the Louvre in Paris as one of its loci. In a passage from his early, feisty and largely plagiarised Histoire de la peinture en Italie (‘History of Painting in Italy’, 1817), Stendhal describes a typical day for visitors to that museum. By the time these legions of culture warriors finally reached the end of the 1,500-foot-long Grand Gallery, punctuated by nine bays whose walls were plastered with paintings from Flemish, Dutch, French and Italian painters, and whose floors sagged from sculptures like the Apollo Belvedere and Laocoön and his Sons, they could barely walk:

Their eyes are red, their faces tired, their lips tightened. Happily, there are couches to sit on. ‘How superb!’ they declare between yawns wide enough to dislocate their jaws. What human eye can remain unaffected under the assault of 1,500 paintings?

(this and subsequent quotations from the French are my own translation)

The short answer is that no human eye – or, rather, no brain behind that eye – can emerge unscathed from such an experience. In museums as monumental as the Louvre, visitors become victims of the sensory and cultural overload that awaits them. This isn’t helped by the Brownian motion of the huge crowds. The pressure of precise itineraries and the presence of so many other people, not all of them well-behaved or speaking sotto voce, ratchets up the tension already present in the very nature of modern tourism: the imperative to see as many must-see sights in as little time as possible. The feeling is contagious. It’s difficult not to let other people set the pace. Not surprisingly, Beyle rebelled against the crushing abundance of paintings at the Louvre, and instead believed its holdings would be better distributed among dozens of smaller museums where people might stop and engage deeply with these great works of art rather than glance at them over their shoulders as they passed at a slow walking pace.

With the burgeoning of modern tourism at the turn of the 19th century, there was a growing market for guidebooks. This proved too great a financial temptation for even well-known writers, like Beyle’s close friend Prosper Mérimée. Not surprisingly, Beyle attempted the genre as well. He did so with little formal training in art and even less desire to repeat what other art critics, whom he had read, had written. Beyle was a tourist pas comme les autres – a trait readily apparent in his own guidebooks. In his Mémoires d’un touriste (‘Memoirs of a Tourist’, 1838), he warns that the only itinerary he follows is what he feels like doing or seeing from one moment to the next, while the only rules he follows are to write spontaneously – ‘It is not because of egotism that I write “I”, but because I cannot otherwise write quickly’ – and to speak his mind: ‘I savour my opinions and will not exchange them to savour the pleasure of fame.’ In the end, Beyle accepts that his only readers will be the happy few armed with the insouciance, like him, to ignore convention and calculation.

That young man has feelings about art that a dapper bourgeois is incapable of summoning

Even if Beyle did not have the technical sense to discuss art properly, he had more than enough sensibility to feel it. He makes the case that a serious art lover must cultivate the feelings spurred by it. This isn’t a matter of grasping a work of art by studying its history and its artist’s biography, but instead of taking the time to allow the painting to grasp you. In the preface to his sly and subversive account of the Paris Salon of 1824, Beyle notes he did not purchase a guide to the exhibition’s hundreds of paintings. ‘I did not want my eyes to be misled by empty reputations and fail to see the true merit of these works.’ More percussively, he offers what we might think of as a trigger warning:

I will tell you frankly and simply my feelings I feel about each of the pictures I will give my full attention. My goal is to make each of you search your soul, analyse your own way of feeling, and thus form your own opinion and way of seeing based on your own character, taste and great passions – that is, provided you do have passions, for unfortunately they are necessary in the judgment of art.

(This too is why, he adds, he prefers to eavesdrop on the observations made by the ‘dishevelled young man with haggard eyes and sharp movements’ than those offered by the better-dressed and behaved visitors. Clearly, that young man has feelings about art that a dapper bourgeois is incapable of summoning. It’s also more likely that the youth looked at the painting rather than the people around it.)

And this, for Beyle, is the raison d’être of art: to make you feel. This is why he devotes as much space to excoriating the neo-classicism of Jacques-Louis David and his followers as he does to embracing the paintings of Delacroix and Ingres. While the ancient and modern figures depicted by David and his school are formally perfect, Beyle declares, they are utterly devoid of life. As an example, Beyle suggests we take David’s The Intervention of the Sabine Women – please. Yes, it is finely balanced and truly monumental, but that is all. Not only are the nude figures ‘without passion’ but, he adds insouciantly, ‘it is absurd to march off to war with no clothes on.’ David and his students are technically adept, but emotionally arrested; to paint the passions, they must not just be seen – they must be felt to your very marrow. ‘I am not saying that all passionate people are good painters,’ Beyle wrote. ‘I am instead saying that all great artists have been passionate men.’

The Intervention of the Sabine Women (1799) by Jacques-Louis David. Courtesy Louvre, Paris

For Beyle, no artist more fully combined these two qualities than Antonio da Correggio. In an epitaph Beyle wrote for himself, Correggio earns a place alongside composers and writers such as Shakespeare, Mozart and Cimarosa as the artist he most loved. When Beyle passes through Modena, the city where Correggio had studied, every woman Beyle glimpses glows with the same features that Correggio gave to Mary in his stunning Holy Night. (This is not an irresponsible flight of imagination: Correggio used local men and women, not idealised types, as models for his saints and virgins.) As Beyle notes, he had to travel to Dresden, where the painting had gone, to see this example of ‘the rarest shades of emotion, which lie forever beyond the range and scope of poetry.’ He stood in front of the tableau, transfixed by both the technical brilliance of Correggio’s subtle use of chiaroscuro but also deeply moved by this depiction of a mother and child, bathed in a golden light – it left him wordless.

Holy Night (1528-30) by Antonio da Correggio. Courtesy the State Art Collections, Dresden

Beyle is again wordless when he reaches Parma, the city where Correggio spent most of his adult life. Crucially, though, the words fail to come not at the city’s cathedral, whose domed ceiling is ablaze with Correggio’s overwhelming fresco The Assumption of the Virgin. Instead, Beyle is drawn to what guidebooks considered a sideshow: the monastery of Saint Paul, where Correggio was commissioned early in his career to paint a fresco on the ceiling of a private apartment. It depicts a scene of the goddess Diana leading children in a hunt. The meaning of the fresco remains something of a mystery, but that hardly bothered Beyle. Perhaps it was because, as was the case at Santa Croce, he was alone in a private room. Perhaps it was because the children were led by a mother-like figure. Or simply because art, when it fuses passion and technique – what Stendhal’s admirer Friedrich Nietzsche called the Dionysian and Apollonian – fuses in turn with those who have known similar passions. Paradoxically, the painting’s subject is not what is most important; instead, it is something undefined but utterly real and deep. There are certain paintings, Stendhal insisted, that give pleasure regardless of the subject they represent, they captivate the eye by a kind of instinct.

The Assumption of the Virgin (1526-30) by Antonio da Correggio, in the Cathedral of Parma, Italy. Courtesy Wikipedia

Fresco of Diana (c1520) by Antonio da Correggio, from the Abbess’s Chamber in the former Monastery of Saint Paul in Parma, Italy. Courtesy Wikipedia

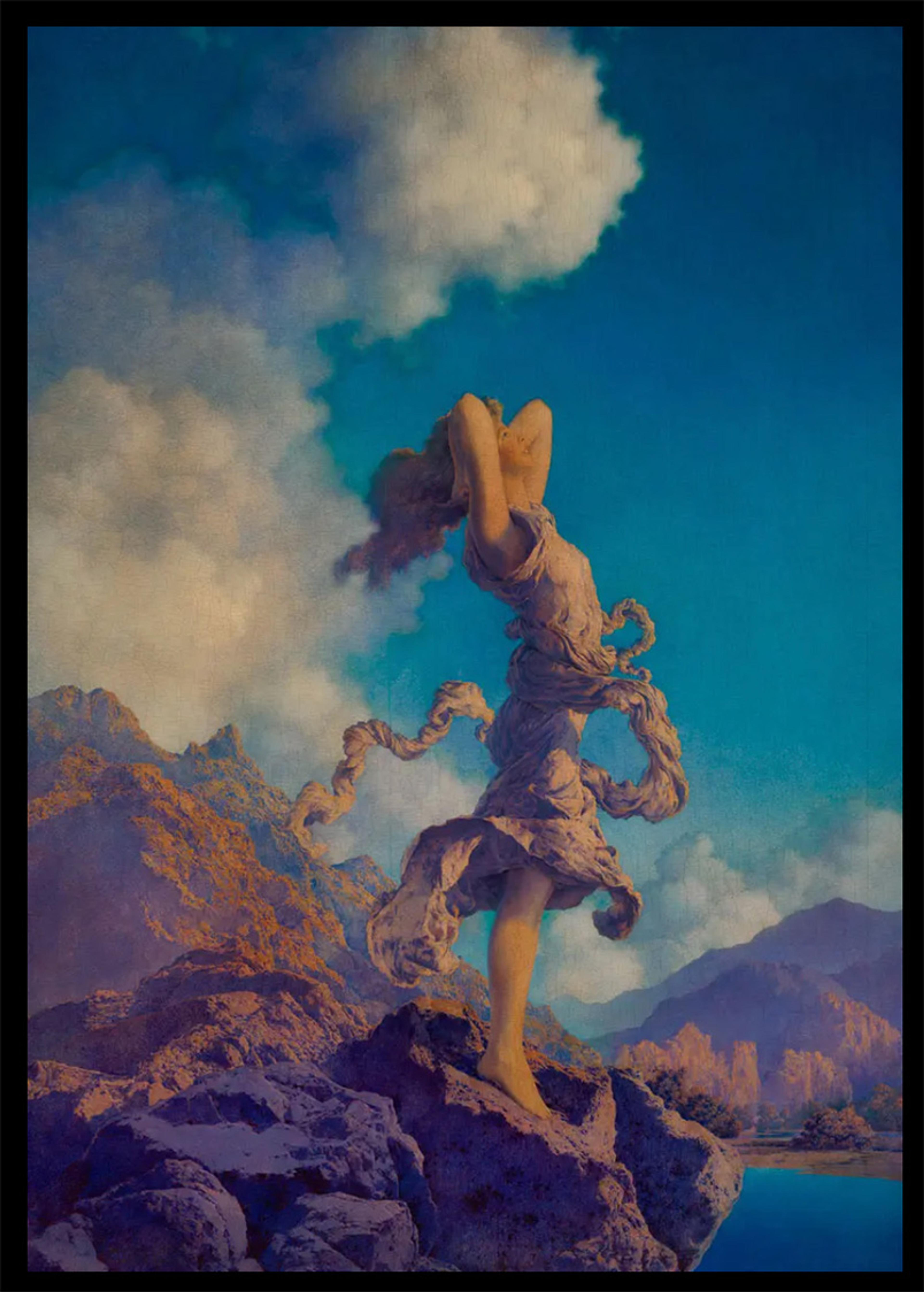

For Beyle, this is the purpose of art. It reminds us of those feelings that, at certain moments of our lives, lift us from our mundane concerns and, well, make us happy. They may even make us feel transcendent. While I have not had many such moments at museums, I have had them elsewhere, often at unexpected moments and, at times, with unexceptional works of art. I still recall one such moment when, still a teenager, I first saw Ecstasy (1929) at a poster shop in a local mall. I was gob-smacked. Maxfield Parrish claimed fame not as an artist who displayed in galleries, but instead whose art decorated calendars and advertisements for industrial firms like General Electric. In Ecstasy, you gaze at the arching figure of a young girl wearing a diaphanous dress while standing, improbably, barefooted on a cliff overlooking a lake – which, of course, carried an erotic charge. But the image was less carnal than spiritual, offering the promise of something greater, something truer than what life in suburban New Jersey had to offer.

Ecstasy (1929) by Maxfield Parrish. Courtesy the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art

I confess I have also very occasionally had such moments in museums. A few years after my Parrish experience, I went backpacking through Europe. While in London, I dutifully visited Tate Britain and wandered into the Clore Gallery where the Turners hang. I have never left it since, still re-imagining the depths of hazy and blinding light of Norham Castle, Sunrise (1845). One of J M W Turner’s last great works, it depicts – nearly decomposes – the hulk of the castle guarding the River Tweed as a few cattle pad across it. But I prefer to stick to the Parrish, if only as a reminder that such moments can happen in malls, no less than in museums.

Norham Castle, Sunrise (c1845) by J M W Turner. Courtesy Tate Gallery, London

In a footnote to De l’Amour (1822), his strange and wonderful reflections on love, Beyle offers one of his most famous and elusive phrases: ‘La beauté n’est que la promesse du bonheur.’ Too often this is translated as ‘Beauty is the promise of happiness’ but the restrictive ‘only’ is crucial. Or, at least, crucial for me. The promise of happiness that floored me via these paintings, hanging either in malls or museums, was just that – only a promise. It turns out that such a promise can never be kept. But that is how it should be. For Beyle, the chase of happiness was precisely that: a chase. Its success is not the capture of happiness, but only its glimpse, one that glimmers with such promise that our lives, rooted in the world, continue to arch towards something greater, something truer.