When Paulo was an undergraduate, he was tasked with taking photographs of neurons. ‘A single cell,’ he came to notice, ‘it’s a whole universe.’ Looking at cells beneath a microscope is not unlike gazing at stars in the sky, Paulo realised. ‘We all know they are there, but until you see them with your own eyes, you don’t have that experience of awe, of wow.’ It was then, as he put it, that he ‘fell in love with these cells for the first time.’

Now a stem cell biologist at a university in the United States, Paulo remains enthralled with ‘pretty’ cells. His desktop background is filled with their images. But the ‘aesthetic’ of stem cells, Paulo insists, is not just in the pretty pictures they make.

‘There is some other type of beauty that is not visual,’ he explained to us in an interview. ‘I’m not sure what it is. Perhaps there is some kind of…’ His voice trailed off. Searching for the right words, Paulo continued: ‘It’s almost an appreciation for the complexity of things. But what you realise is that it’s all uncoverable. We can know it all.’

Paulo fell in love with science for the visual beauty of nature, but his continued passion for it owes to what we call the beauty of understanding – the aesthetic experience of new insight into the way things are, when encountering the hidden order or inner logic underlying phenomena. To grow in understanding, Paulo reflected, is ‘something very satisfying’. ‘The beauty in science,’ he emphasised, ‘that is, at least for me, a huge motivator.’

Public conversations about beauty in science tend to focus on the beauty anyone can see, say, in photographs of stars like those released from the James Webb Space Telescope, or the beauty that physicists, for instance, ascribe to elegant equations. But these foci miss something important. Over the past three years, we have studied thousands of scientists on three different continents, asking them about the role of beauty in their work. Our research left us convinced that the core aesthetic experience science has to offer is not primarily about sensory experiences or formulas. At the deepest level, what motivates scientists to pursue and persist in their work is the aesthetic experience of understanding itself. Centring the beauty of understanding presents an image of science more recognisable to scientists themselves and with greater appeal for future scientists. Moreover, it foregrounds the need for institutionally supporting scientists in their quests for understanding, which are all too often stifled by the very system on which they depend.

‘Beauty’, for many, is the last word that comes to mind when thinking of science. Where the word ‘science’ connotes ‘objective’, ‘value-free’ and ‘rational’, the term ‘beauty’ evokes the ‘subjective’ and ‘emotional’. Such associations are reinforced by the nerdy and aloof scientist stereotype, which remains common among young people, according to decades of research using the ‘Draw-A-Scientist Test’. Modern education systems institutionalise this dichotomy with the division of the sciences and humanities into separate classes and colleges.

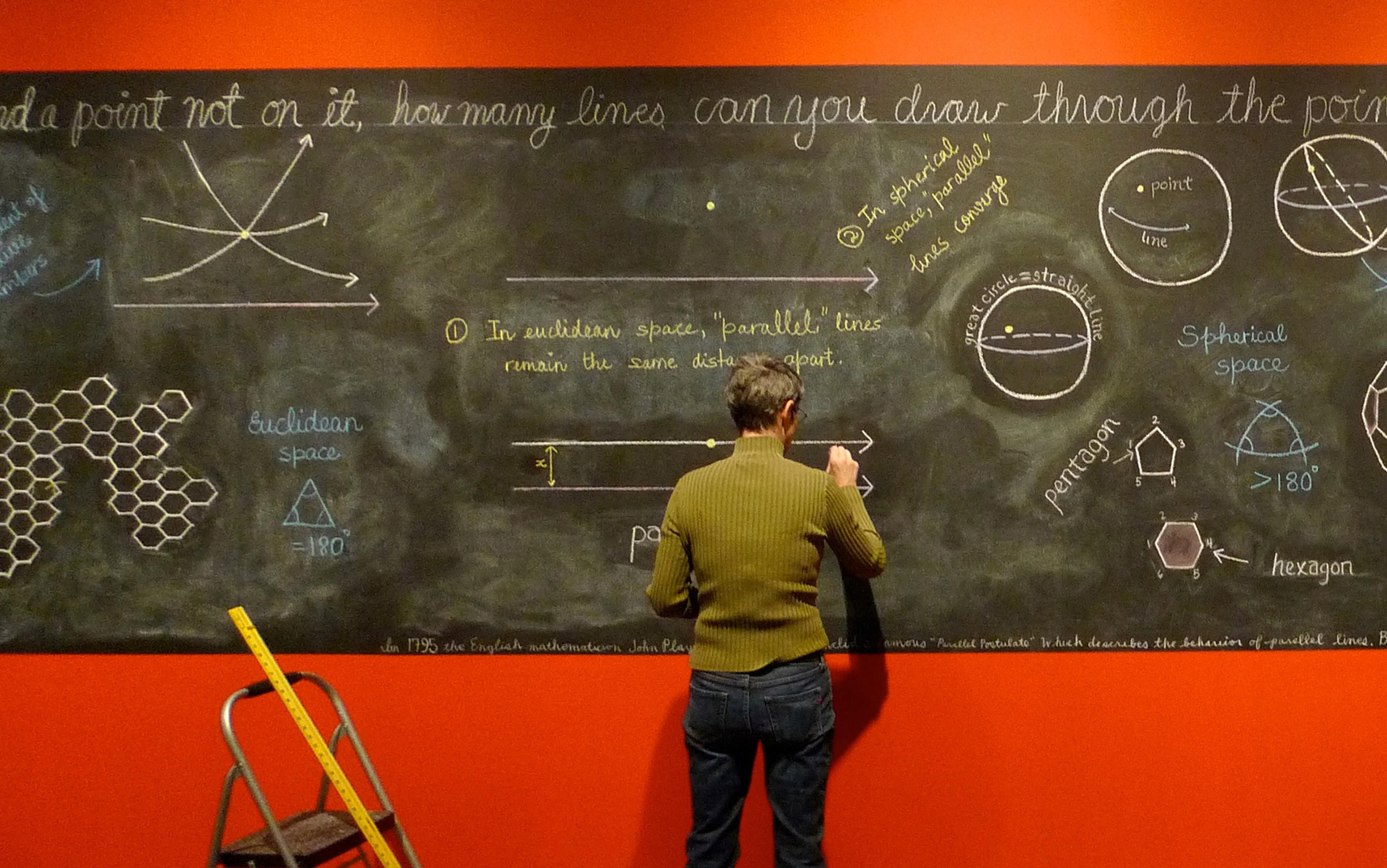

Such tensions hark back at least to the 19th century, when English Romantic poets such as William Blake and John Keats accused scientists of stripping beauty and mystery away from nature. Keats, despite his own considerable scientific training, reputedly complained that Isaac Newton ‘destroyed all the poetry of the rainbow, by reducing it to the prismatic colours.’ In his poem Lamia, Keats writes: ‘all charms fly / At the mere touch of’ natural philosophy or science, which, he laments, will ‘clip an Angel’s wings, / Conquer all mysteries by rule and line,’ and ‘unweave a rainbow’.

Are aesthetic experiences in science the rare prerogative of geniuses?

This stereotype of science, however, contrasts with what scientists have had to say in recent decades, from Nobel Prize-winning physicists such as Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar and Frank Wilczek to the British biologist Richard Dawkins. These scientists portray science as an impassioned endeavour, and a font of beauty, awe and wonder. Dawkins, for instance, aims at Keats when he argues in his book Unweaving the Rainbow (1998) that, far from being a source of disenchantment, science nourishes an appetite for wonder. ‘The feeling of awed wonder that science can give us,’ Dawkins contends, ‘is one of the highest experiences of which the human psyche is capable.’ ‘It is a deep aesthetic passion,’ he writes, ‘to rank with the finest that music and poetry can deliver.’ These testimonies call to mind pioneering scientists like Alexander von Humboldt, whose passion for beauty fuelled his work, as Andrea Wulf shows in her exquisite biography The Invention of Nature (2015).

Such cases, however, raise several questions: are aesthetic experiences in science the rare prerogative of geniuses, or do most contemporary scientists often find beauty in their work? How do encounters with beauty shape scientists personally, and their practice of science – whether positively or negatively?

To answer these questions, we conducted the world’s first large-scale international study of the role of aesthetics in science. In 2021, our team surveyed nationally representative samples of nearly 3,500 physicists and biologists in four countries: India, Italy, the United Kingdom and the United States. Over the past three years, we also interviewed more than 300 of them in-depth. Our data have made clear to us not only that science is an aesthetic quest – just like art, poetry or music – but also that the heart of this quest is the beauty of understanding.

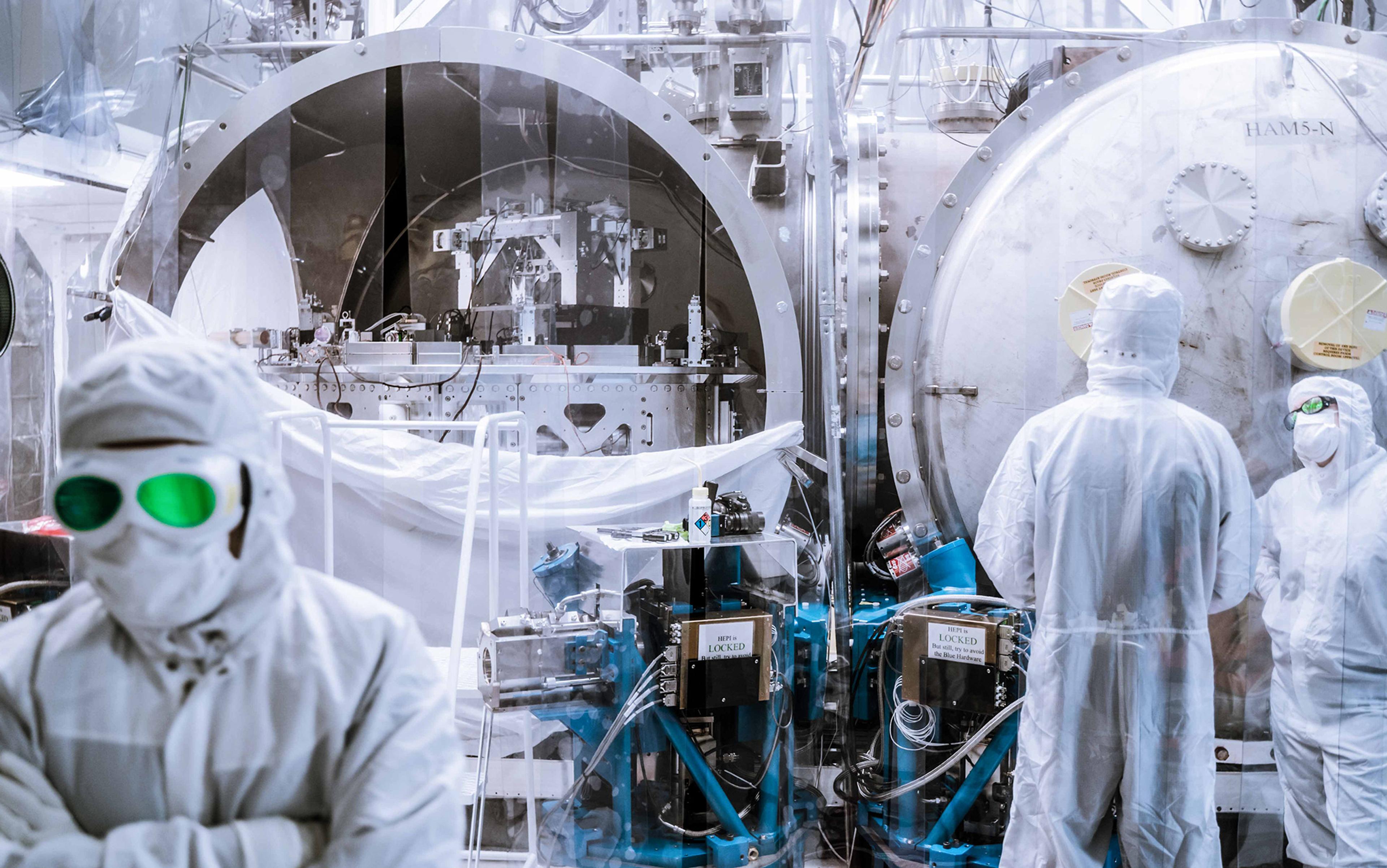

Our research identified three types of beauty in science, each of which shapes the course of scientists’ work in distinct yet interconnected ways. What is visually or aurally striking – what we refer to as sensory beauty – is a common source of beauty for scientists. Indeed, the majority of scientists (75 per cent) see beauty in the objects and phenomena they study, from cells to stars, and in the symmetries, simplicity and complexity of nature, which can evoke emotions of awe and wonder. Many even find such beauty in scientific models and instruments. As was the case for Paulo, sensory beauty is often what draws in people to science. For instance, a biologist in the UK told us that beauty was what drew her to her field of study: ‘I personally think that a pollinator visiting a flower, both of those things to me are incredibly beautiful. And the two of them interacting with each other, I think, is one of the most beautiful things in nature, which is why I study pollination.’

Of course, not all aspects of scientific work are beautiful in this sense. Many respondents told us about the absence of sensory beauty in their work. ‘To be honest with you, if anything, I would describe the real practice of science as ugly or hideous,’ one UK physicist told us. ‘There is an awful lot of boring drudge work, frustration, cursing, swearing, like I’m sure there is in any developmental job, and beautiful is not a word I would use at that point.’ We also found no shortage of complaints about ugliness in scientific workplaces such as dark, dingy labs.

But even those who do not find much sensory beauty in their work can encounter beauty in another sense. Physicists in particular often rely on what we call useful beauty. This second type of beauty involves treating aesthetic properties such as simplicity, symmetry, aptness or elegance as heuristics or guides to truth.

Historically, many theories considered beautiful turned out to be wrong, while ugly ones turned out to be right

For instance, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Murray Gell-Mann said that ‘in fundamental physics, a beautiful or elegant theory is more likely to be correct than a theory that is inelegant.’ Paul Dirac, another Nobel Prize-winner, went so far as to say that ‘it is more important to have beauty in one’s equations than to have them fit experiment.’

Not all physicists, however, are enamoured with useful beauty. There is no guarantee the aesthetic properties that facilitated understanding in the past will do so in the future. And, historically, many theories considered beautiful turned out to be wrong, while ugly ones turned out to be right – and then were no longer considered ugly. Some argue that physics is in a similar situation today. In Farewell to Reality (2013), Jim Baggott complains that theories of super-symmetry, super-strings, the multiverse and so on – driven largely by beautiful mathematics – are ‘fairytale physics’. They are ‘not only not true’, he contends, they are ‘not even science’. Similarly, in Lost in Math (2018), Sabine Hossenfelder argues that aesthetic criteria have become a source of cognitive bias leading physics astray.

Our survey found that physicists are evenly divided when it comes to the reliability of useful beauty. On the question of whether beautiful mathematics is a guide to truth, 34 per cent disagree while 35 per cent agree; regarding whether elegant theories are more likely to be correct than inelegant ones, 42 per cent disagree while 23 per cent agree. As to Dirac’s claim about beauty in equations being more important than experimental support, a striking 77 per cent of physicists disagree, while only 8 per cent agree with the statement.

Beauty’s utility in science is not limited to physics or to its heuristic role in theory selection; it can also be significant when designing experiments in physics and biology. ‘I try to make our experimental design as elegant and as direct as possible, which for me is a form of beauty,’ a US biologist told us. ‘Because the less effort we have to put into getting an answer the better. The faster, the cleaner, the fewer different parameters we have to control for in an experiment, the more convincing and clean, I think, the information will be that they get out of it.’ Many scientists similarly emphasised the relevance of aesthetic considerations for designing a project, writing code and analysing data. Beauty, thus, has relevance in science beyond theory choice.

The third type of beauty, which we find is most prevalent and argue is the most important, is what we call the beauty of understanding. The vast majority of scientists describe moments of understanding as beautiful. In our surveys and interviews, when asked where they find beauty in their work, scientists regularly pointed to times when they grasped the hidden order, inner logic or causal mechanisms of natural phenomena. These moments, one UK physicist told us, are ‘like looking into the face of God for non-religious people – how you can look at something and think, oh my God, that’s how things actually work, that’s how things are!’ A US biologist concurred: ‘It is recognising,’ he explained, ‘this is what’s going on. There’s a leap to the truth, or a leap to a sense of generalisation or something that is beyond the particular but in some way represents the real thing that’s there, the real thing that’s going on. We think of that as beautiful.’ Nearly 95 per cent of scientists in the four countries we studied report experiencing this kind of beauty at some point in their scientific practice.

If the notion of the beauty of understanding seems strange, that is due to a dualistic perspective – the philosophical roots of which stretch back through Immanuel Kant to René Descartes – that treats reason and emotion, objectivity and subjectivity, science and art as binary. But there is an alternative perspective, which brings into view the continuity of reason and emotion, objectivity and subjectivity, science and art. In this view, it is as natural to recognise beauty in understanding as in a sunset.

In 1890s, the polymath and founder of American pragmatism Charles S Peirce coined the term ‘synechism’ for ‘the tendency to regard everything as continuous‘ (the term’s roots are in the Greek word for ‘continuous’). Embracing this philosophy of continuity, his fellow pragmatist John Dewey developed a theory of aesthetic experience encompassing science and art as differing only in ‘tempo and emphasis’, not in kind. Each, Dewey argued, manifests experience that has been transformed from a state of fragmentation, turbulence or longing to a state of integration, harmony or – his favoured term – ‘consummation’. The process of transformation is a struggle, but that only enhances the satisfaction of the consummatory experience it brings about. From initial puzzles through the ugliness of data collection to the closure of theoretical explanation, Dewey’s theory of aesthetic experience describes just the sort of journey the scientists we spoke with articulated when describing their quests for the beauty of understanding.

Once one considers, with Dewey, aesthetic experience as a potential latent in any fragmented experience – recognising its scope extends beyond sensory or useful beauty – one can see that science enables aesthetic experience through, for instance, the integration of seemingly disparate observations and ideas in moments of understanding. The process of moving from a puzzling observation to a theory that accounts for it, or from a theory to a discovery of evidence it predicts, can be long, arduous and messy – a far cry from sensory beauty. But when understanding emerges, so does beauty as the quality making it stand out against the rough course of experience that ran before. Feeling the beauty of the moment clues in scientists to the possibility that they just may have arrived at something transformative – emotion and reason work hand in hand. In our interviews, many scientists recalled voicing their sense of beauty in moments of understanding with terms like ‘aha’, or evoked feelings of a ‘high’ or a ‘kick’ to describe it. As Dewey noted in his essay ‘Qualitative Thought’ (1931), such ‘ejaculatory judgments’ voiced ‘at the close of every scientific investigation … [mark] the realised appreciation of a pervading quality,’ namely, the distinctly aesthetic quality of the experience. It is this quality that scientists refer to as ‘beauty’ in relation to understanding.

Half of academic scientists now quit after five years. A toxic work culture may be pushing them out

Both sensory and useful beauty are oriented to the beauty of understanding. The beauty scientists find in the phenomena is an invitation to deeper understanding. And it is this understanding that imparts value to the technologies, experiments and theories employed in research. The deeper significance of the aesthetic properties that scientists appeal to lies in their potential for facilitating understanding.

The beauty of understanding, further, can help scientists persist through the challenges of research. After telling us of his passion for the beauty in science, Paulo shared that, a year earlier, he nearly quit his job. ‘I was hospitalised out of stress,’ he admitted. ‘I had shingles. That stuff is an endogenous virus that comes out when you’re stressed. It was horrible.’

Taken aback, we asked him to explain what stressed him out so much. ‘I was having just so many grants rejected. And I was like: “Oh my gosh, what’s going to happen now?”’ Like most scientists, Paulo relies on competitive research grants to do his work. He had spent countless hours applying for research funding, but was having no success. Not only had he become physically ill, he was also sick of trying. He made a LinkedIn account. ‘I was ready to look for another job,’ he said. ‘I was completely devastated by the fact that I just didn’t want to write more grants.’ And, without funding, his scientific quest would end.

Paulo is no outlier in considering leaving his position due to stress. Depression and anxiety have become commonplace among researchers in their early careers. More and more scientists seem to be leaving their jobs; 50 per cent of academic scientists these days quit after five years. A toxic work culture may be pushing them out. Leading scientific publications such as Nature have issued warnings of a mental health crisis in science, which is causing attrition that threatens the future of the profession.

Paulo nearly became one of these casualties. Fortunately, a conversation with a mentor intervened. ‘Everything just changed all of a sudden, because she was just telling me the grants are not really the most important thing in the world.’ His mentor told him not to neglect ‘all the other good things’ he was doing, and to take pride that his students were ‘very motivated about science’. When Paulo faltered in his motivation to pursue the grants he needed for research, renewal came with realising that his guidance was invaluable for his students’ quests for the beauty of understanding.

Paulo did not quit his job. And he eventually got the funding he needed to continue his research. Beauty helped him persevere.

Beauty permeates science, from the sensory beauty that often draws people to a scientific career in the first place, to aesthetic criteria such as elegance, which shapes theory selection and experimentation for better or worse. But most important is the beauty of understanding, an aesthetic experience in its own right, the quest for which deepens scientists’ motivation to pursue and persist in their careers.

Appreciating the aesthetic nature of the scientific quest is crucial for understanding science and why people devote their lives to it. Two-thirds of the scientists we studied insist it is important for scientists to encounter beauty, awe and wonder in their work. But, for too long, popular culture has been saturated with false myths about science and beauty, misguiding young people about what it means to be a scientist and what doing science is actually like. As we learned through our research, scientists are motivated by beauty. Their quests to achieve the beauty of understanding are fuelled by both reason and emotion. Dualistic assumptions about ‘objective’ science and ‘subjective’ judgments of beauty get in the way of seeing the continuity of science with other aesthetic ventures.

‘It’s because I’m an artist. Physicists are artists who can’t draw’

Making the beauty of understanding central to public conversations about science will draw much-needed attention to questions of how institutions can better support and leverage scientists’ motivating passion. How many scientists would find greater motivation for their work if there were fewer barriers to realising the beauty of understanding that drives them in the first place? Institutional incentives to ‘publish or perish’ and bring in short-term grant funding inadvertently contribute to an environment where many scientists like Paulo find themselves burnt out, or so disillusioned with toxic competition that they leave academia altogether. For scientists to thrive, institutional incentives need to capitalise upon, not crush, the beauty that drives scientists. Funders might offer flexible and longer-term research grants that facilitate creative interdisciplinary collaborations. Considering that more frequent aesthetic experiences at work are associated with higher levels of wellbeing among scientists, workshops incorporating aesthetic and appreciative reflection about research practices may help scientists reconnect with the deeper, motivating beauty of their work.

As Andrea Wulf told us in a conversation, science is a palace with many doors; yet our educational systems tend to guide students through only a few conventional entry points. The beauty of understanding is a neglected pathway. By centring such beauty in public discussions about science, we can better engage bright, creative youth, helping them see that scientists are people like themselves. Exactly this is what inspired one young woman we interviewed to become a physicist.

At age 17, Tricia had babysat for a physicist’s young children, so she was used to hearing questions about what makes a rainbow and why the sky is blue. But what surprised and enchanted her was hearing these very questions posed by the children’s father. He explained his wonder this way: ‘It’s because I’m an artist. So physicists are artists who can’t draw.’ This ‘triggered something in me’, Tricia told us, as she had always wanted ‘to paint to describe nature’ but lacked the skill.

This physicist’s example convinced her she need not give up her dream entirely. What she discovered, rather, was that science could allow her to capture the beauty of nature in an even more profound way – not just through images, but through understanding. Now a theoretical particle physicist at a university in the UK, Tricia is living her dream by uncovering the hidden structures of the natural world, painting with the brush of theory. Who else might become a scientist if only they, like Tricia, were shown the beauty of understanding that science offers?