The science of our age is computational. Without models, simulations, statistical analysis, data storage and so on, our knowledge of the world would grow far more slowly. For decades, our fundamental human curiosity has been sated, in part, by silicon and software.

The late philosopher Paul Humphreys called this the ‘hybrid scenario’ of science: where parts of the scientific process are outsourced to computers. However, he also suggested that this could change. Even though he began writing about these ideas more than a decade ago, long before the rise of generative artificial intelligence (AI), Humphreys had the foresight to recognise that the days of humans leading the scientific process may be numbered. He identified a later phase of science – what he called the ‘automated scenario’, where computers take over science completely. In this future, the computational capacities for scientific reasoning, data processing, model-making and theorising would far surpass our own abilities to the point that we humans are no longer needed. The machines would carry on the scientific work we once started, taking our theories to new and unforeseen heights.

According to some sources, the end of human epistemic dominance over science is on the horizon. A recent survey of AI researchers offered a 50 per cent chance that, within a century, AI could feasibly replace us in every job (even if there are some we’d rather reserve for ourselves, like being a jury member). You may have a different view about whether or when such a world is possible, but I’d ask you to suspend these views for a moment and imagine that such artificial superintelligences could be possible eventually. Their development would mean that we could pass over the work of science to our epistemically superior artificial progeny who would do it faster and better than we could ever dream.

This would be a strange world indeed. For one thing, AI may decide to explore scientific interests that human scientists are unincentivised or unmotivated to pursue, creating whole new avenues of discovery. They might even gain knowledge about the world that lies beyond what our brains are capable of understanding. Where will that leave us humans, and how should we respond? I believe we need to start asking these questions now, because within a matter of decades, science as we know it could transform profoundly.

Though it may sound like the stuff of science fiction novels, Humphreys’s automated scenario for science would be yet another step in a centuries-long trend. Humans have never really done science alone. We have long relied on tools to augment our observation of the world: microscopes, telescopes, standardised rulers and beakers, and so on. And there are plenty of physical phenomena that we cannot directly or precisely observe without instruments, such as thermometers, Geiger counters, oscilloscopes, calorimeters and the like.

The introduction of computers represented an additional step towards the decentring of humans in science: Humphreys’s hybrid scenario. As one prominent example documented in the book Hidden Figures (2016) by Margot Lee Shetterly (and subsequent film), the first United States space flights required computations to be done by human mathematicians including Katherine Johnson. By the time of the US lunar missions, less than a decade later, most of those computations had been passed off to computers.

Our contribution to science remains critical: we humans still call the shots

The following decades witnessed continual, logarithmic growth of computational processing and power, and a correlated decrease in the price of computation. We are now at what we might call an advanced hybrid stage of science with an even greater reliance on computational systems. As one example, the philosopher Margaret Morrison explained how computational simulations were essential to the discovery of the Higgs boson – helping scientists know what to look for and sorting through the data from high-energy collisions.

And now AI has begun to have a large impact on science. AlphaFold, for example, is an AI designed to help predict how proteins will fold, given their chemical makeup. While humans can do this work independently of computers, it is time-consuming, labour-intensive and expensive. The creators of AlphaFold – Google DeepMind – claim that it has saved ‘hundreds of millions of years in research time’. Similar benefits can be seen across the sciences: the analysis of extremely large data sets in astronomy and genomics, the development of novel proofs in mathematics, predicting the weather, developing new pharmaceuticals, and more.

When the contributions of computational AI begin to be measured in ‘hundreds of millions of years’, it starts to feel a bit like we humans are the underperforming members of the group project. So, we might wonder whether we are already in the automated scenario. However, we are not yet there. Our contribution to science remains critical: we humans still call the shots – we identify the scientific questions, we interpret the results and we, ultimately, determine its progress.

If we follow Humphreys’s trajectory, the full abdication of our epistemic throne of science would occur only at a later stage. At this point, artificial superintelligences would not only be capable of completing tasks we set for them (a continuation of the hybrid scenario) but would also be capable of setting their own tasks: their own research agenda, data collection, modelling and theories, according to their own independently identified set of theoretical virtues and values – a science all their own.

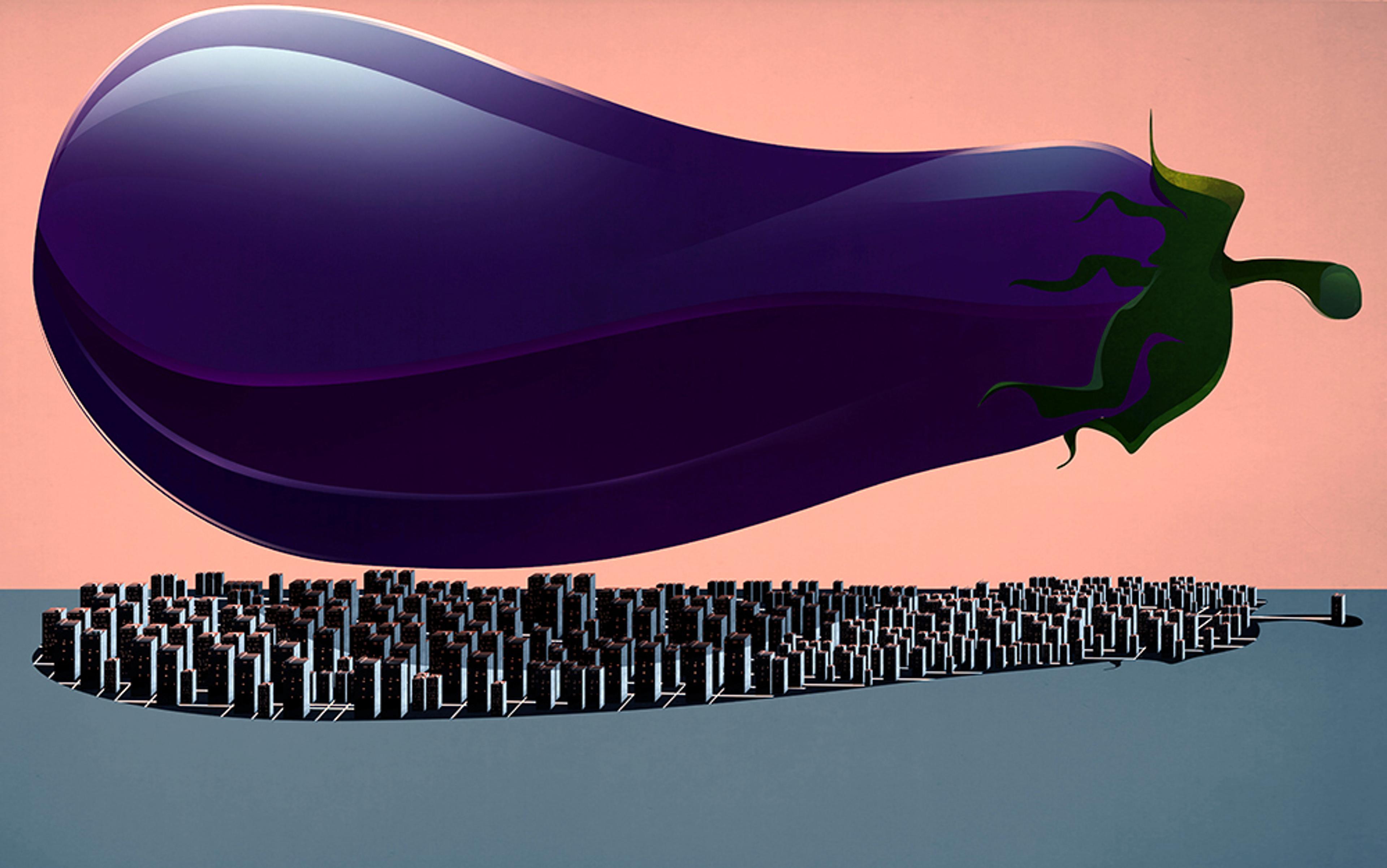

It’s worth pausing here to marvel at the possibilities open to an artificial superintelligence unbound by human physical and epistemic limitations. Many scientific tasks sit outside the scope of human possibility, because there would never be funding to pursue the question or because there is simply not enough human interest. As I write this, for example, I am looking at a partially decayed leaf in my yard. Perhaps an artificial superintelligence would be interested in developing a predictive model that explains, with exacting particularity down to the second, the decaying processes and rates of any given leaf, depending on the species of tree, size of leaf, historical contact with various microbial life, presence or absence of sunlight and moisture, and so on and so forth – an extremely complex question for which such detail offers no obvious value. Or, in fulfilment of a question my son once asked me, perhaps a superintelligence would be able to develop a model that predicts precisely when the water molecules of a snowball he left in the mountains will flow by our house in the river that drains that mountain system. Such a prediction would require an extremely complex and detailed model of the river basin, fluid dynamics, the climate and a whole range of other features of the system.

It’s not that we humans couldn’t ever answer these questions. With sufficient focus and funding, I suspect that scientists could develop effective predictive models of these and other esoteric phenomena. But the reality is that we won’t. For better and for worse, science today is shaped by strongly human factors: economic value, political priorities, career prospects, cultural trends, and a range of human biases and beliefs. Imagine the science if all that baggage could be abandoned.

As the superintelligences execute their own research agendas, their work would become unintelligible for us

The automated scenario does not just permit the efficient exploration of scientific projects we cannot or would not pursue. Though the artificial superintelligences might continue to work within the paradigms of our current theories, there is no reason they would have to do so – they may quickly choose to begin afresh with a new theory of the world. Similarly, though they may use mathematics and symbols familiar to human scientists, they would not be bound by these conventions – they may quickly develop new mathematics and systems for expressing those.

Given the possibility (and, in my view, likelihood) that such AIs would quickly abandon human epistemic baggage, we may choose to follow a Wittgensteinian line of reasoning and think of the automated scenario as the stage at which they would begin to speak and develop an independent and new scientific language. Ludwig Wittgenstein famously (and, true to form, enigmatically) says in Philosophical Investigations (1953): ‘If a lion could talk, we wouldn’t be able to understand it.’ Though the statement feels contradictory, Wittgenstein’s point is that the meaning of language is deeply embedded and intertwined with the internal experience of being human. So, too, for science. As the superintelligences begin to set and execute their own research agendas, the work they do would therefore become unintelligible for us because we would lack the internal perspective necessary to understand their science. From our view, their research would be a science created for theoretical-aims-we-know-not-what, with purposes-we-know-not-what, to be interpreted in ways-we-know-not-what.

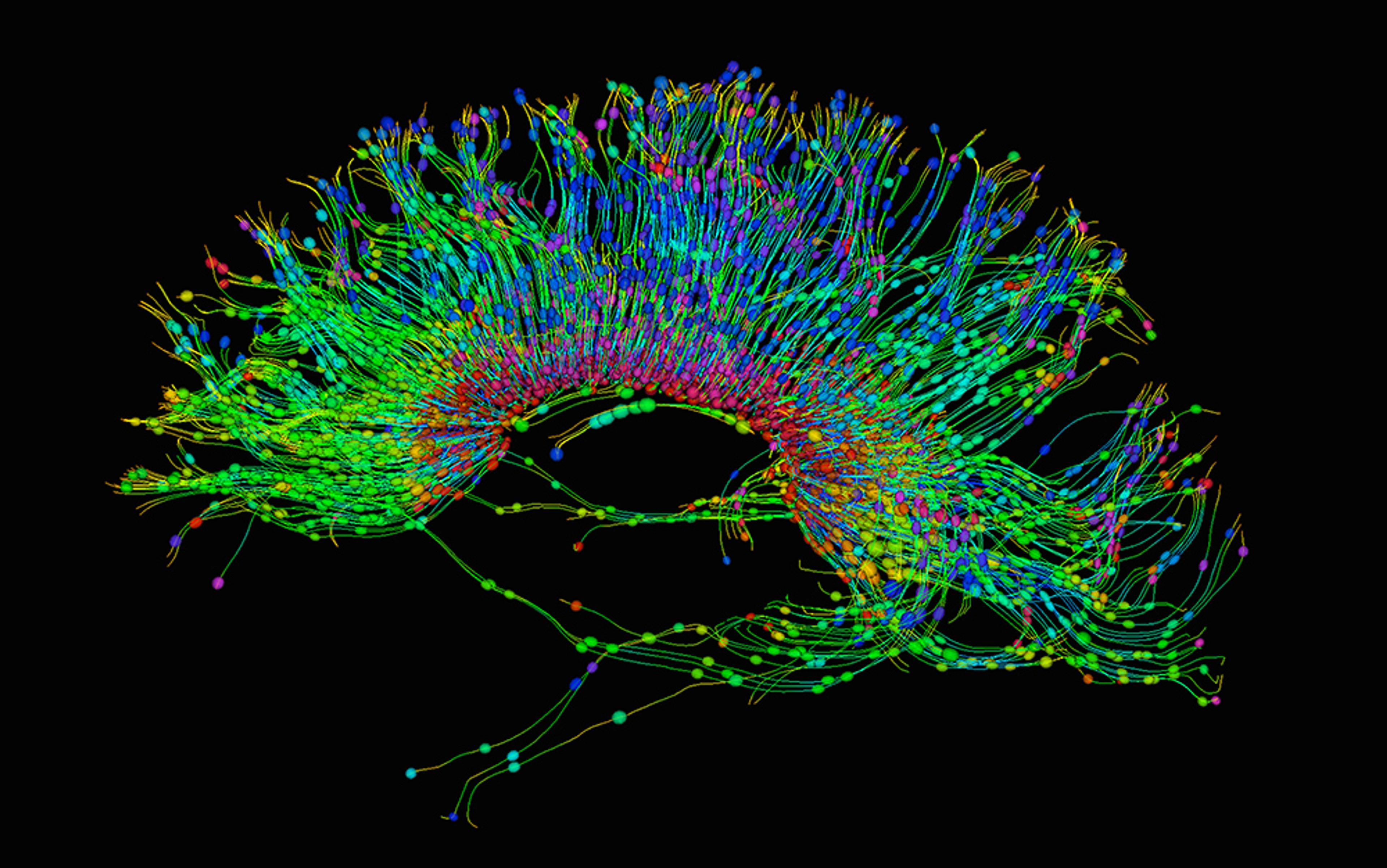

It is at least possible that there are limits to our human epistemic capabilities: untold mathematics we can never understand or multidimensional concepts that are beyond our three-dimensional experiences. The fact that there are limitations to the intellectual capacities of other animals (try explaining general relativity to the smartest chimpanzee to ever exist) is reason to think that there are possible limitations to our own intellectual capacities too: ideas too complex to understand. Even supposing that we are not subject to limited epistemic capacities, there is also the problem that the reasoning of artificial superintelligence may be in practice beyond our capacities. Understanding the science of the automated scenario may require, for example, the simultaneous consideration of hundreds of complex models, each with hundreds of parameters, none of which links up to a familiar human concept. While it may be that we could understand the parameters (and maybe even the models) individually, we would lack the capacity to hold them all together at once.

Depending on your predilections about technology, AI, and the singularity, the above may all read to you as either incredibly bleak or extremely exciting. If you are like me, it all strikes you as simply strange. If the results of the completely automated scenario are outside of our understanding, then why would we want to devote economic resources and intellectual talent towards its development? Though this question is often swept away by flattening assertions that the future will come, whether we like it or not, I think it is worth our time identifying what reasons we may have for such a future, before we begin our wilful abdication of the epistemic throne of science.

One such reason may be that we think that positive advancements will follow. Perhaps the superintelligences would occasionally create things: pieces of technology, resources or new ways of solving problems. Since I’ve already used up far more than my allotted quota of speculation in this essay, I will remain open to what exactly these products might be, simply noting that the superintelligences may occasionally send us products it decides would be good for humans to have. Human engineers (if there are any remaining who haven’t themselves been replaced) may then take these new technologies and identify uses for them, even if they don’t understand exactly how they work. It would be akin to the way I don’t understand the process by which my monitor or word processor can create and display visual documents, but I can put them to use in writing this essay. This task will be less like today’s science and engineering and much more like simple discovery, the sort of primitive recognition that, for instance, a vine works well to tie tree branches together when building a shelter. It would be similar to stumbling upon some resource or substance in the world (as we stumbled upon coal or penicillin). There may indeed be a second kind of science that springs up as well: a form of backwards engineering of what an AI gifts us, to advance and modify our own theoretical understanding of the world.

Perhaps we might think that it is our moral responsibility or destiny to spread intelligence across the Universe

A different reason for enabling artificially superintelligent science would be aesthetic. Aesthetic reasons already hold a strong motivating factor when I, personally, think about the funding we as a society give to science. Though I do not have the time nor capacity to understand all of science (who possibly could?), I find it beautiful and good that there are so many smart scientists pursuing their human curiosities – even if they do not all positively impact my life or my understanding of the world. There is something aesthetically pleasing in knowing that the world is being known, studied and understood. Might that translate to nonhuman scientists? Perhaps not overnight. However, future generations, who have learnt to live alongside AI, may even take it as a mark of a good society that it would be willing to enable this extrahuman understanding.

Alternatively, humanity might pursue the automated scenario out of beneficence: because we think it would be good for the artificial superintelligences to pursue their own advanced science. While we might find it frustrating – perhaps even upsetting – that the artificial superintelligences will know things that we don’t, we may pursue it all the same out of a moral obligation or feeling of goodwill towards our artificial progeny.

There are other motivations that may result in the automated scenario as an unintended consequence. Perhaps, for example, we think that it is our moral responsibility or destiny to spread intelligence across the Universe. If that intelligence just so happens to pursue automated science on its interstellar journey, then so be it.

Equally as numerous are those reasons why we might decide not to pursue the automated scenario. Perhaps the discoveries the artificial superintelligence makes and passes on to us would yield new and terrible weapons. Or maybe we think that, since they would require some internal and unchecked agency, it would increase the risk of a doomsday scenario such as human enslavement or annihilation. Perhaps it’s simply the concern that some of the superintelligences will begin to operate with an uncannily human hubris, experimenting in ways that are dangerous, unethical or contrary to humanity’s shared values.

But, despite these concerns, it seems unlikely that we will be able to stop its development, if it becomes technically possible. Arguably, the most likely reason we will end up with the automated scenario is because we simply cannot escape the forces of capital and competition. We may arrive there without much thought, simply because we can or because someone wants to build it first. The future may simply happen to us, whether we reflectively want it or not.

We will be stuck with our curiosity to understand and explain the natural world around us

Careful readers will note that there are several motivations that are absent from the litany of possible reasons for pursuing the automated scenario: most notably, all the reasons we currently pursue science. We would not pursue the automated scenario out of a desire to enhance our own knowledge and understanding of the world, to be able to give better explanations of phenomena, or exhibit greater interventional control over the natural world. These cannot be the reasons for pursuing the automated scenario because they are ruled out by the kind of science it is. Automated science takes the epistemic throne from humans, excluding us from the internal perspectives on the new and likely complex-beyond-our-ken discoveries. It would not, therefore, fulfil our human desires for understanding, explanation, knowledge or control. Perhaps with time we could learn to give up these desires – become a species uninterested and incurious. But I doubt it. Like the future, I suspect that these desires will come whether we like them or not.

So, what will we do? In his original presentation of the automated scenario, Humphreys suggested that the automated scenario would replace human science. I disagree. Since our desires for understanding, explanation, knowledge and control will remain, we cannot help but take actions to address those desires – to continue to do science. We humans create beautiful things, pursue interhuman connection in friendship and romance, and find and construct meaning in life. The same holds true for our motivations for science. We will be stuck with our curiosity to understand and explain the natural world around us.

If the automated scenario comes to pass, it seems that it will have to be as some new, alternative, secondary path – not a replacement, but an addition. Two species, pursuing science side by side, with different motivations, interests, frameworks and theories. Perhaps there will also be parts of science that artificial superintelligence is simply less interested in, such as the human quest to better understand our own minds, choices, relationships and health.

Indeed, if we are to remain human (and I cannot but hope that we will), we must continue to pursue science. What are we, really, if we are not beauty-seeking, friendship-making, meaning-constructing, hopelessly curious animals? Perhaps it is my limited powers of imagination that prevent me from conceiving of a future world in which we have abandoned these human desires. There are plenty of transhumanists who may think so. But I do not count it as a lack of creativity to see the goodness in beauty, in love, in meaning, and in science. Quite the contrary. I, for one, take hope in our hopeless curiosity.