It’s not just AI systems that raise questions about consciousness – the products of synthetic biology do too. In recent years, researchers have discovered how to grow cerebral organoids – self-organising three-dimensional cellular systems derived either from human pluripotent stem cells or, more recently, human fetal cells. Increasingly, organoids are being fused to create ‘assembloids’, complexes of interacting organoids. For example, Sergiu Pasca’s laboratory at Stanford University has created an assembloid that models the human spinothalamic pathway, a neural circuit critical for the transmission of sensory information from the body to the brain. Does this assembloid merely model the generation and transmission of sensory information, or might it actually have conscious experiences of its own?

Although questions about consciousness in assembloids and AI systems are novel, they are instances of a more general question that is as old as the study of consciousness itself: what kinds of entities have the capacity for consciousness? It’s now generally accepted that mammals and birds are capable of consciousness, but there is little consensus about consciousness in fish, reptiles, amphibians, cephalopods or insects. Pressing questions about the distribution of consciousness arise even within our own species. For example, there are long-standing debates about whether consciousness might be present from (or even before) birth, or whether it arises only weeks, perhaps even months, after birth.

Most discussion of the distribution problem has focused on how we might identify consciousness in systems that are very different from ‘us’. There is, however, a more fundamental issue raised by the distribution question: what do we even mean when we ask whether bots, bees or babies are conscious? This is not an epistemic question but a semantic one. Although semantic questions are often derided as sterile and unfruitful (‘That’s just semantics,’ typically said with a withering roll of the eyes), they are unavoidable. If we’re going to take seriously the question of what kinds of systems belong with us in the ‘consciousness club’, we need to ask not only what ‘consciousness’ means, but how it comes to mean what it does.

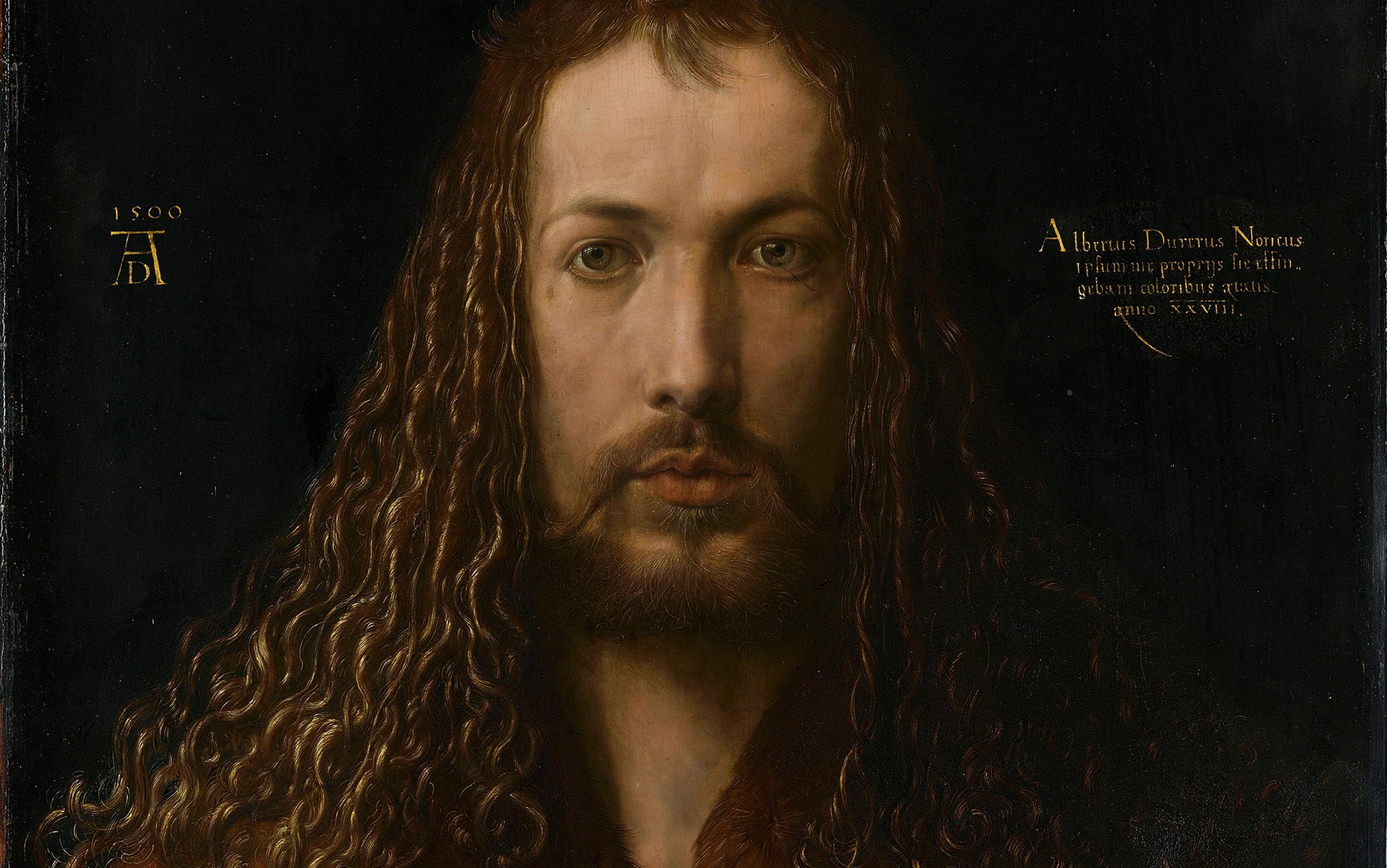

Like many natural language terms, ‘consciousness’ is polysemous, having multiple (albeit related) meanings. In one sense of the term, ‘consciousness’ is a synonym for wakefulness. Consider, for example, the following sentence, taken from The Logic of Definition (1885) by the Scottish philosopher W L Davidson: ‘The mind’s wakeful activity is consciousness – consciousness as opposed to dormancy, dreamless sleep, swoon, insensibility …’

It’s clear, however, that debates about the distribution of consciousness aren’t about wakefulness. When the computer scientist Geoffrey Hinton claims that AI systems are already conscious, he surely isn’t suggesting that they are awake; conversely, those who reject the possibility of neonatal consciousness don’t deny the obvious fact that neonates undergo periods of wakefulness. But if the distribution problem isn’t about wakefulness, what is it about?

There are two strategies for answering this question. One strategy appeals to synonyms: bits of language that purportedly capture the intended meaning of ‘consciousness’. Popular synonyms for ‘consciousness’ (in the relevant sense) include ‘awareness’, ‘sentience’ and ‘subjective experience’. Another frequently invoked synonym is the phrase popularised by the philosopher Thomas Nagel: to be conscious is for there to be ‘something it’s like’ to be you.

This is definition by pointing: ‘consciousness’ is the taste of a lemon, the blueness of the sky

Appealing to synonyms may help to clarify what it is that we’re not talking about, but there are serious limits on how much illumination we should expect from this approach. For one thing, if a term or phrase really is synonymous with ‘consciousness’ then it should be as mysterious as ‘consciousness’ itself, in which case it’s hard to see how helpful appeals to it could possibly be. More fundamentally, synonyms take you from one piece of language to another but what we really want is something that takes us from language to some aspect of reality itself.

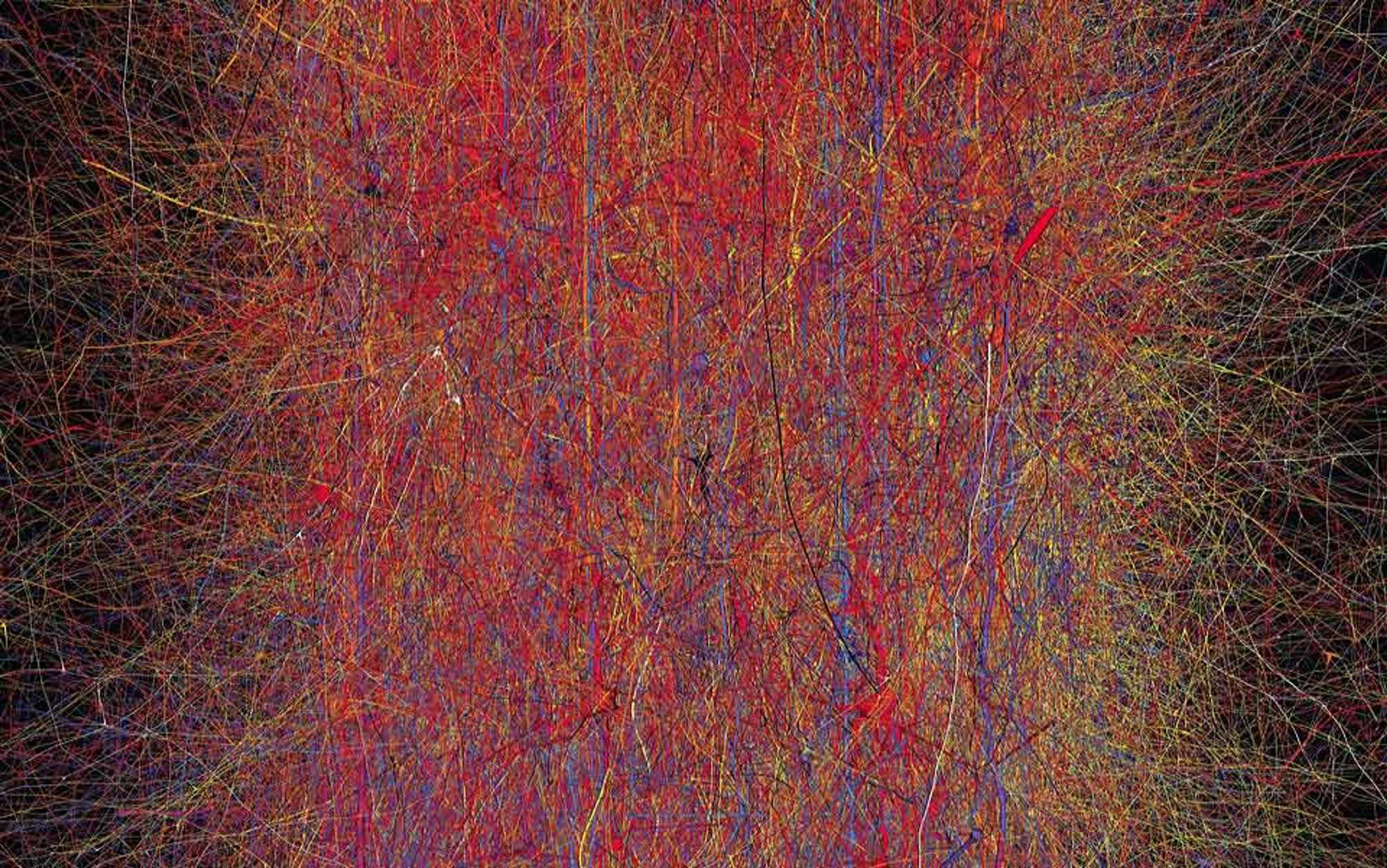

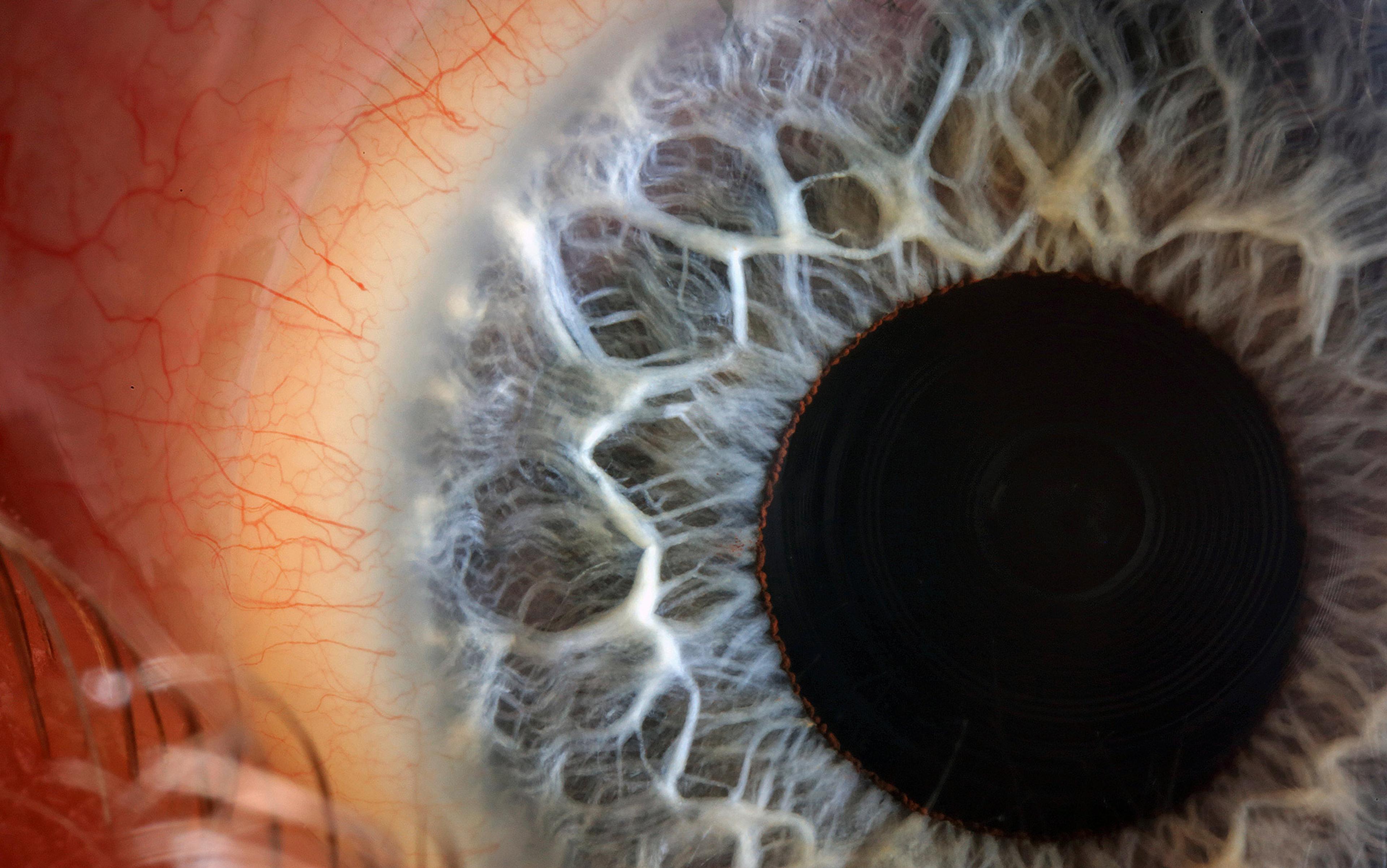

This is where the second strategy for defining ‘consciousness’ enters the picture. Don’t know what ‘consciousness’ means? It’s the ‘experience of dark and light … the sound of a clarinet, the smell of mothballs … the felt quality of emotion; and the experience of a stream of conscious thought’ (David Chalmers). It’s the experiences associated with ‘tasting a lemon, smelling a rose, [or] hearing a loud noise’ (Frank Jackson). It’s ‘the pain felt after a brick has fallen on a bare foot, or the blueness of the sky on a sunny summer afternoon’ (Patricia Churchland).

This is definition by pointing. Instead of explaining what ‘consciousness’ means by relating it to another piece of language, one captures its meaning by relating it to something non-linguistic – the experience of dark and light, the taste of a lemon, the blueness of the sky on a sunny summer afternoon.

This approach to defining ‘consciousness’ is intuitively compelling, but how exactly does it work? And what kind of insight into consciousness might it deliver?

One widely held view is that attending to examples of conscious experience enables one to grasp its essence. The idea here is not that we can tell whether something is conscious merely by attending to our own experiences. Rather, the idea is that attending to our own experiences enables us to grasp the concept of consciousness, and grasping the concept of consciousness in turn reveals what it is to be conscious. As a parallel, consider what is involved in grasping the concept of triangularity: if you’ve grasped the concept of a triangle, then you know what it is to be a triangle. We might call this the manifest understanding of consciousness, for it holds that pointing to examples of consciousness makes manifest its very nature.

There is much that is appealing in this conception of consciousness. As countless philosophers have pointed out, introspective access to our own experiences does seem to provide us with direct access to the very nature of consciousness. But, for all that, the manifest account of consciousness may well be wrong. To see why, consider jazz.

Suppose that someone asks you what jazz is. Rather than attempt to define ‘jazz’ by providing synonyms, you’re more likely to point to instances of the genre. ‘There,’ you might say to your audience as you put on (say) Ella Fitzgerald’s Like Someone in Love, Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue or John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme – ‘that’s jazz.’ As the philosopher Ned Block once noted, the question ‘What is consciousness?’ can be answered much like Louis Armstrong reportedly answered the question ‘What is jazz?’: ‘If you got to ask, you ain’t never gonna get to know.’

The debate wasn’t about who had played what notes first, but whether what they had played qualified as ‘jazz’

But although treating jazz as a manifest concept is undeniably tempting, it’s at odds with the historical record. What counts as ‘jazz’, even as ‘bad jazz’, has been a matter of debate – some of it humorous, much of it heated – since its very beginnings. (I’m indebted to Graeme Boone and Michael Ullman in what follows.)

‘Livery Stable Blues’, recorded by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band in 1917, is commonly regarded as the first jazz recording ever made, but there is much debate about who first played jazz. In 1938, an episode of the radio show Ripley’s Believe it or Not! described William Handy as the originator of jazz in the early 1900s. His rival Ferdinand (‘Jelly Roll’) Morton rejected that claim, arguing in a letter to the jazz magazine DownBeat that he himself was the first to play jazz. Happy to cede that claim to Morton, Handy responded with a letter to DownBeat entitled ‘I Would Not Play Jazz If I Could’. The debate wasn’t so much about who had played what notes first, but whether what they had played qualified as ‘jazz’. (Incidentally, the ‘If you got to ask, you ain’t never gonna get to know’ line is sometimes ascribed to Morton rather than Armstrong.)

The swing craze of the 1930s generated renewed debate about the boundaries of jazz. Was Glenn Miller’s ‘In the Mood’ jazz? Some argued that it wasn’t; others had little doubt that it was – and was great jazz to boot. Debate about the boundaries of the category was reignited with the arrival of bebop in the mid-1940s. Jazz, many felt, was essentially music for the dancehall and, whatever else it was, bebop wasn’t danceable. By the late 1950s, the question of what counted as jazz had moved on from bebop to what we now know as ‘free jazz’. Ornette Coleman’s provocatively named The Shape of Jazz to Come (1959) was lauded by many – ‘[He’s] doing the only really new thing in jazz since … the mid-40s,’ claimed the pianist John Lewis – and frequently appears on lists of the greatest jazz albums. However, at the time, many refused to recognise it as jazz. ‘I don’t know what he’s playing,’ said Dizzy Gillespie, ‘but it’s not jazz.’

These debates undermine the idea that jazz has an essence – something that determines whether or not we ought to apply the term to new cases. Instead, they suggest that the concept of jazz is governed by a cluster of loosely related properties – what Ludwig Wittgenstein called ‘family resemblances’. Sometimes those resemblances are strong, and the case in question obviously falls within the relevant category. Davis’s Kind of Blue and Coltrane’s Giant Steps, highly innovative albums recorded in the same year as Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come, clearly qualified as jazz, for their innovations fell within familiar parameters. But the innovations of Coleman’s work – its ‘organised disorganisation’, as Charles Mingus put it – were more fundamental, raising genuine questions about whether the label of ‘jazz’ was appropriate.

The concept of ‘jazz’, I suggest, isn’t a manifest concept but a conventional concept. Although particular instances of jazz are real enough, what bundles them together as instances of jazz is heavily dependent on our decisions. As it turned out, the relevant gatekeepers (music critics, jazz musicians, record label executives) decided to recognise The Shape of Jazz to Come as jazz, but had they withheld that honorific they wouldn’t have been making a mistake. Prior to their decisions, there was simply no fact of the matter as to whether The Shape of Jazz to Come was jazz.

Although ‘jazz’ might seem to be a manifest concept, I’ve argued that it’s better thought of as a conventional concept. But what about consciousness? Perhaps Block was right to suggest that there’s a parallel between ‘consciousness’ and ‘jazz’, not because they are both manifest concepts, but because neither is.

While the conventionalist account of consciousness is less influential than the manifest account, it should be taken with equal seriousness. As we have already noted, ‘consciousness’ is not a piece of specialised scientific vocabulary (like ‘gene’, ‘proton’ or ‘quantitative easing’) but a term of ordinary English. And ordinary language terms are often conventional – or, at least, have aspects that are heavily conventional. They are designed to deal with the warp and weft of everyday life, and we shouldn’t assume that they legislate for every possible case. Perhaps the rules governing the use of ‘consciousness’ apply only to us (and systems that are relevantly like us), and are not what Wittgenstein called ‘rails invisibly laid to infinity’.

Conventionalism allows normative considerations to drive verdicts about the distribution of consciousness

If conventionalism is right, then complete knowledge of the physical and functional properties of a system might fail to deliver an answer to the question of whether it’s conscious. That’s not because the question of whether something is conscious involves some ‘further fact’ that is unconstrained by its physical and functional properties (such as whether it has a soul), but because the rules governing ‘consciousness’ simply don’t apply to it. If that’s right, then decisions about whether to admit bots, bees or babies into the ‘consciousness club’ may be less a matter of what the world turns out to be like and more a matter of how we decide to use words.

Many factors might be relevant when considering whether to ascribe consciousness to a system, but the dominant driver is likely to involve the normative dimensions of consciousness: the bearing that consciousness has on an entity’s moral and legal status. Here, conventionalism inverts widespread assumptions about the natural order of things. Intuitively, we tend to assume that figuring out who’s in the consciousness club is the task of science, and that ethicists, lawyers and policymakers ought to respond to the scientific verdict (whatever that turns out to be). Conventionalism, by contrast, allows normative considerations to drive verdicts about the distribution of consciousness. Want to provide newborn human beings with a suite of ethical and legal protections? Ascribe consciousness to them. Want to withhold those protections from the most recent AI systems? Refrain from ascribing consciousness to them.

So, we’ve got two models of the concept of consciousness on the table: the manifest view (‘consciousness as triangularity’) and the conventional view (‘consciousness as jazz’). If you don’t find either view compelling, you wouldn’t be alone – but what might an alternative look like? A foray into the history of biology furnishes some clues.

Following the death of his teacher Plato in 347 BCE, Aristotle spent time on the Aegean island of Lesbos, birthplace of the poet Sappho. Lesbos is dominated by an enormous lagoon, now known as ‘Aristotle’s Lagoon’, and it was here that Aristotle encountered three members of the cetacean family: dolphins (probably striped dolphins and common dolphins), the harbour porpoise, and the fin whale.

Cetaceans puzzled Aristotle. Although he occasionally described them as fish, he also recognised that they have lungs and breath air (unlike fish), noting that dolphins had been observed with their noses above the water snoring. He also knew that cetaceans resemble us and other mammals in giving birth to live young and feeding them with milk. But despite an awareness of these facts, Aristotle couldn’t quite bring himself to classify cetaceans with other mammals, instead treating them as a class in their own right, alongside fish, birds and what he called ‘viviparous quadrupeds’ (terrestrial mammals).

The Queen’s Quarters at Knossos Palace, Crete. The original dolphin frescoes are on display in the Heraklion Museum. Photo by Andy Montogomery/Flickr

Despite increasingly detailed knowledge of their anatomy, cetaceans continued to baffle scientists long after Aristotle’s time. For example, the 16th-century French naturalist Pierre Belon distinguished between ‘fish with blood’ and ‘fish without blood’. The former category included cetaceans, together with fish, turtles, pinnipeds, crocodiles and the hippopotamus; the latter included aquatic invertebrates such as squid and octopuses. Indeed, it wasn’t until the 10th edition of Carl Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae (1758) that science finally recognised cetaceans as mammals, albeit ‘the most peculiar and aberrant of mammals’, as the 20th-century palaeontologist George Gaylord Simpson once put it.

What motivated this recognition? Was the classification of cetaceans as mammals akin to the classification of Ornette Coleman’s music as jazz, or are the two cases fundamentally different?

Our situation with respect to consciousness is akin to Aristotle’s with respect to cetaceans

The standard view here – and one to which I subscribe – is that the two cases are very different. The classification of cetaceans as mammals was motivated by the realisation that the commonalities between cetaceans and (other) mammals are more fundamental and extensive than the commonalities between cetaceans and other aquatic animals. Linnaeus had, in effect, discovered that the class of mammals reflects a ‘joint in nature’, and that cetaceans fall on one side of that joint and other aquatic animals fall on the other. Cetaceans were mammals before 1758, and they would have been mammals even if biologists had never realised this. By contrast, musical categories such as jazz are not constrained by joints in nature in the way that biological terms are.

This, then, gives us a view on which ‘consciousness’ picks out a genuine joint in nature – what philosophers call a ‘natural kind’. The natural kind account agrees with the manifest account in holding that there is something like an ‘essence’ to consciousness, but it rejects the assumption that grasping the concept of consciousness acquaints us with that essence. Instead, this account holds, our current situation with respect to consciousness is akin to the situation that Aristotle found himself in with respect to cetaceans. In the same way that empirical investigation was needed to reveal what it is to be a cetacean, so too (the natural kind account holds) empirical investigation is needed to reveal what it is to be conscious. Until we have a scientific understanding of consciousness, we won’t really know what it means to say that bots, bees or babies are – or, as the case may be, are not – conscious.

It might seem obvious that ‘consciousness’ is a natural kind concept. After all, one might think, a commitment to the natural kind view is implicit in the very idea of a science of consciousness. (There isn’t, of course, much sense to be made in the idea that there might be a science of triangles or jazz.) Of course, even if ‘consciousness’ is used with the intention to pick out a natural kind, that intention may not be successful. Perhaps ‘consciousness’ will turn out to resemble other ordinary language terms such as ‘fish’ or ‘tree’ – terms that are undeniably useful in many everyday contexts, but don’t capture deep joints in nature. Alternatively, consciousness might turn out to involve not one but multiple natural kinds, much in the way in which the folk notion of heaviness suggests both mass and weight. At this point, we simply don’t know what the science of consciousness might uncover. In this sense, then, the very language of consciousness is, to some degree, hostage to the fortunes of consciousness science.

As the attentive reader might have guessed, my sympathies lie with the natural kind account. My primary aim, however, has not been to argue for the superiority of that view over its rivals, but to explain what this debate is and why it matters to the question of how consciousness is distributed. That question is not merely epistemic (‘How might we tell whether something is conscious’) but also semantic (‘What does it mean to ascribe consciousness to something?’) That semantic question is challenging not just because it raises a meta-semantic question (‘What determines what “consciousness” means?’), but also because that meta-semantic question raises, in turn, a meta-meta-semantic question (‘How should we go about figuring out what determines what consciousness means?’)

Debates about semantics (let alone meta-semantics or meta-meta-semantics!) might seem far removed from the serious, and increasingly urgent, questions concerning the possibility of consciousness in bots, bees and babies. Rather than amuse ourselves with forays into the philosophy of mind and language (it’s often said), we should instead focus on trying to grasp what these systems can do and how they function. That desire is understandable, but it is also mistaken, born of a failure to grasp the complexity of our words and the concepts they embody. Philosophy alone won’t solve the problems of consciousness, but if you’re serious about trying to figure out who’s in the ‘consciousness club’, you can’t afford to ignore the question of how words lock on to the world.