Listen to this essay

22 minute listen

When I’m birdwatching, I have a particular experience all too frequently. Fellow birders will point to the tree canopy and ask if I can see a bird hidden among the leaves. I scan the treetops with binoculars but, to everyone’s annoyance, I see only the absence of a bird.

Our mental worlds are lively with such experiences of absence, yet it’s a mystery how the mind performs the trick of seeing nothing. How can the brain perceive something when there is no something to perceive?

For a neuroscientist interested in consciousness, this is an alluring question. Studying the neural basis of ‘nothing’ does, however, pose obvious challenges. Fortunately, there are other – more tangible – kinds of absences that help us get a handle on the hazy issue of nothingness in the brain. That’s why I spent much of my PhD studying how we perceive the number zero.

Zero has played an intriguing role in the development of our societies. Throughout human history, it has floundered in civilisations fearful of nothingness, and flourished in those that embraced it. But that’s not the only reason it’s so beguiling. In striking similarity to the perception of absence, zero’s representation as a number in the brain also remains unclear. If my brain has specialised mechanisms that have evolved to count the owls perched on a branch, how does this system abstract away from what’s visible, and signal that there are no owls to count?

The mystery shared between the perception of absences and the conception of zero may not be coincidental. When your brain recognises zero, it may be recruiting fundamental sensory mechanisms that govern when you can – and cannot – see something. If this is the case, theories of consciousness that emphasise the experience of absence may find a new use for zero, as a tool with which to explore the nature of consciousness itself.

Zero began its life as an imprint on wet clay. Around 5,000 years ago in Mesopotamia, the Sumerian people devised a revolutionary method for number-writing. Instead of inventing new symbols for ever-increasing numbers, they designed a system whereby the position of a symbol inside a number corresponded to that symbol’s value. If this seems confusing, it’s probably because the idea is so familiar it becomes obfuscated by explanation. Consider the numbers 407 and 47. Both contain a ‘4’ yet, in each, ‘4’ represents different values (400 and 40, respectively). The way we interpret this symbol correctly is from the column it sits in within its number (the hundreds or tens, for example). While this may seem like a mere change in format, the consequences of such positional notation were vast: it allowed for rapid recording of large numbers and simple methods of calculation.

At some point, a problem emerged: what were the Sumerians to do when a particular column had no number in it, as in the number 407? It was here that zero was born: Sumerians placed a diagonal wedge between two numbers to signify ‘nothing in this place’.

Despite the power afforded by positional notation and a mathematical symbol for nothing, it met with resistance and even derision as it made its way out of the Middle East. Greek civilisations left limited records corresponding to zero’s use, and they maintained use of a non-positional numerical system, much like Roman numerals. In fact, the Greek aristocracy – those who studied mathematical frameworks – actively shunned the use of zero. Greece was a land of geometry, and its scholars sought to describe the world using lines, points and angles. The concept of ‘nothing’ had no obvious home. Their love of logic was equally obstructive: how could nothing be something? Aristotle concluded that nothingness itself did not – could not – exist.

St Augustine equated it with the devil: nothingness was the greatest evil

However, the usefulness of positional notation to tradespeople helped zero to percolate beneath the indifference of those who shunned it. Because of this, it was the working classes who controlled zero’s destiny, bringing it from Babylon to India via trade routes around the 3rd century BCE.

In contrast to Greece’s logicians, nothingness was woven throughout the philosophical foundations of Indian culture. The variety of words Indians used for ‘nothing’ in different contexts (such as the immensity of space, the ether, or emptiness) depicts an Indian system that held ‘nothing’ as a describable thing in itself, not merely an absence of something else. Within this atmosphere, zero flourished. Astronomers and mathematicians such as Brahmagupta devised and delineated the mathematical rules associated with zero. Any number minus itself equalled zero; any number multiplied by zero was zero, and so on. No longer was zero simply a punctuation mark signifying an empty column; zero was now an established concept – on equal standing with other numbers.

The earliest known use of a hollow circle to represent zero is thought to have come from the city of Gwalior in central India in 876, but again its popularity among the trading class means that earlier relics of zero, which were marked only on paper or bark, may have been lost across the trade routes of previous centuries. Through these routes, the concept – in its advanced form – returned to the Middle East before entering circulation in European society, most notably by way of a young travelling merchant known as Fibonacci. In 1202, Fibonacci published his Liber Abaci (‘The Book of Calculation’), which introduced the concept of zero to a European audience. Yet still zero was opposed and ridiculed. The unfamiliar rules needed to calculate with the Arabic numerals led to frequent miscalculations, and zero’s association with nothingness was deemed to be in direct opposition to godliness: if God had created the world out of nothing, it was self-evident that nothingness was to be avoided. St Augustine equated it with the devil: nothingness was the greatest evil.

Again, the working class proved essential in advancing zero’s use. With the introduction of double-entry bookkeeping, which tradespeople used to record income and outgoings, zero’s utility finally took hold in Europe. Around the 15th century, the intellectual class could ignore it no longer, and zero began to be embraced. Perhaps most notably, in the late 17th century, zero allowed the scientists Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Isaac Newton to independently formulate the tenets of calculus – central to which was the computation of mathematical functions’ minima and maxima. For this, zero was fundamental.

Something had – at last – come from nothing. As the polymath Leonhard Euler affirmed, ‘nothing takes place in the world whose meaning is not that of some maximum or minimum’. This something could potentially unlock the secrets of the Universe.

Zero’s delayed uptake throughout history is echoed in children’s late mastery of the number. While other positive numbers correspond to observable entities in the real world, zero is useless for counting. As Alfred North Whitehead quipped: ‘No one goes out to buy zero fish.’ Understanding, and using, zero requires a move away from the physical world into the abstract world of concepts, which may be why children take longer to master zero, compared with other countable numbers.

In experiments, preverbal infants are competent at tracking the number of items displayed to them. When developmental psychologists show babies a sequence of images with, for example, four toys, they’re surprised to then suddenly see five toys. Similar experiments have been done to reveal how young children can perform simple calculations implicitly. If five-month-olds see a puppet placed behind a screen that already covers what they believe is another puppet, they will stare longer if the screen is lifted to reveal three puppets – suggesting they are sensitive to correct and incorrect calculations. This ability vanishes, however, when the result should be zero puppets.

As children grow older, they begin to exhibit a rudimentary understanding of zero’s relationship to ‘nothing’ but, still, they fail to fully grasp its numerical qualities. For example, preschoolers who know that zero means ‘no things’ still believe that one is the smallest number. Likewise, if they’re asked to compare whether zero is smaller than another number, they tend to perform as if they’re merely guessing. In other studies, young children have been able to do these kinds of comparison tasks, but only when the word ‘nothing’ is used in lieu of the word ‘zero’. These studies reinforce the entanglement of zero and absence: to conceive of zero as a number, it is first mapped on to the category of ‘nothingness’ before taking its place at the start of the number line. Even when adult humans successfully conceptualise zero as a small number, it still poses cognitive difficulties. For instance, people are more error-prone when classifying zero as odd or even (despite being told that zero is, in fact, an even number) and it takes longer to read zeros than other small numbers, indicating greater taxation of the cognitive system.

Our ability to symbolise the zero may have developed from non-symbolic representations of absence

Given these behavioural idiosyncrasies, it is natural to wonder how zero is represented in the brain. But this question has only recently become a subject of scientific study. Less than 10 years ago, two different labs found converging evidence regarding the representation of zero in the brains of nonhuman primates. By recording activity from individual neurons while showing the monkeys different numbers of dots, the experimenters could identify neurons that were uniquely interested in specific quantities. Both studies found cells that responded more to empty sets (zero dots) than they did to other numbers of dots. Some of these ‘zero neurons’ cared exclusively for empty sets and disregarded all other numbers of dots equally. For the first time, researchers had demonstrated that there were neurons in the brain that specifically coded for zero. And that’s not all: they also found other zero neurons – towards the front of the brain – that exhibited a more graded pattern of activity: firing most when monkeys saw an empty set, but also firing a little when they saw one dot, and a little less when they saw two dots, and so on. Importantly, these neurons reflected zero’s conception as a number at the beginning of the number line.

Last year, two new studies contributed to the goal of characterising the neural basis of zero – this time in humans. These studies were able to examine the uniquely human ability to represent zero symbolically – as a ‘0’. One study, which looked at the activity of single neurons in people’s brains, replicated the findings from the monkey studies, this time for dot patterns and numerals. It also revealed how the neurons that responded to empty sets showed a slightly different kind of activity to neurons that responded to a positive number of dots. Because of this difference, it’s possible these neurons might represent a more fundamental category of ‘nothingness’ – as opposed to ‘somethingness’ – in the brain, again illustrating a deep connection between zero and absence.

This complemented an experiment I conducted with Stephen Fleming, using magnetoencephalography, which measures the combined activity of thousands of neurons, during numerical tasks involving symbolic zeros and empty sets. Again, the activity of different groups of neurons showed zero to be situated at the beginning of the brain’s number line for both empty sets and symbolic zero. However, in our experiment, the brain activity corresponding to empty sets was – at least in part – similar to that produced in response to symbols of zero. This again adds weight to the idea that our ability to symbolise the concept of zero may have developed from simpler non-symbolic representations of absence.

Taken together, these studies begin to provide initial evidence for a view – first proposed by the neuroscientist Andreas Nieder in 2016 – that the human brain’s representation of zero may share properties with a more fundamental ability to perceive ‘nothing’ itself.

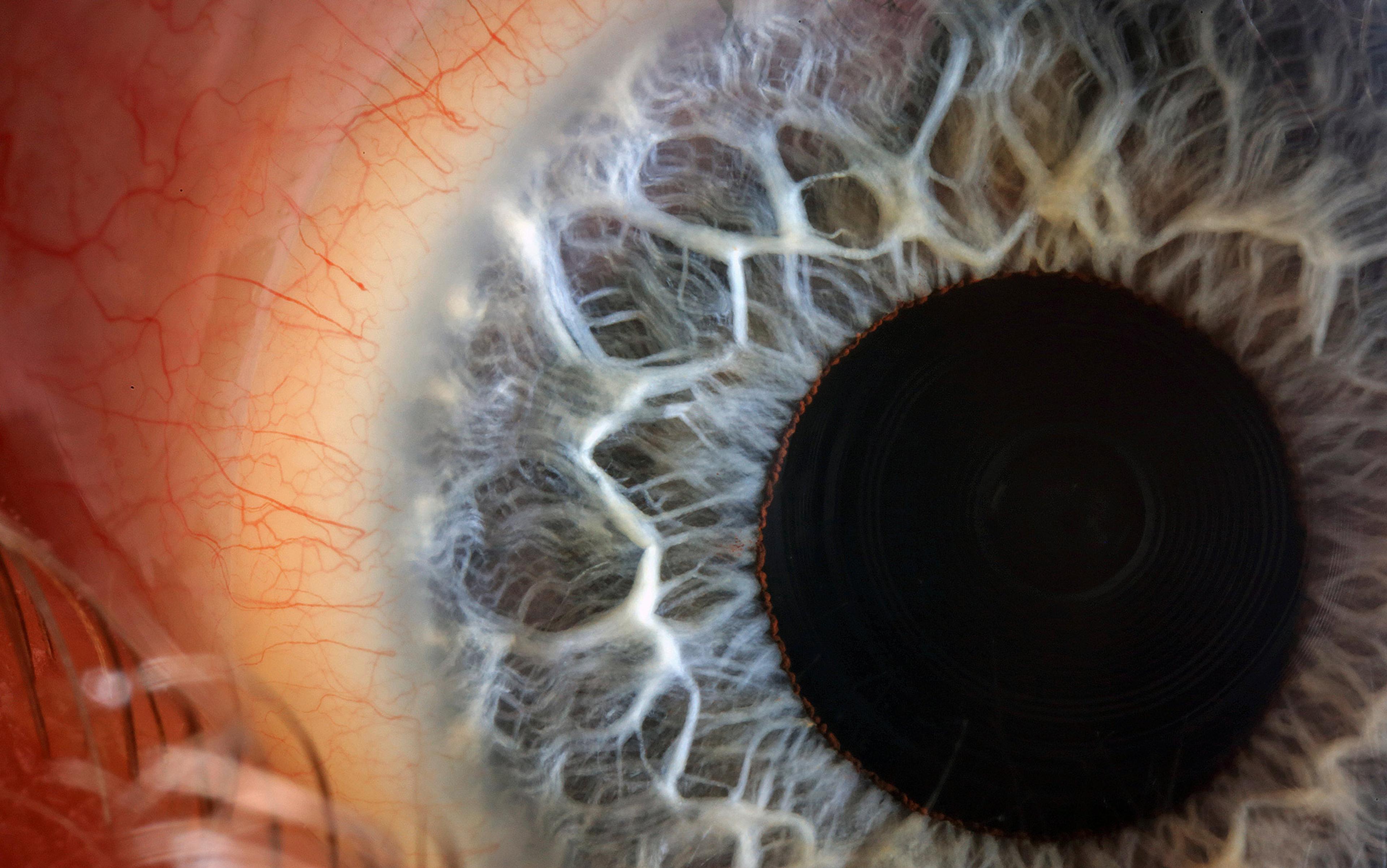

What, then, does it mean to perceive an absence, or nothing? Such experiences can be translated into the laboratory by asking people to find degraded images among visual ‘noise’: ‘Did you see a pattern, or was it just noise?’ It turns out that – much like understanding zero – the question of what it takes to perceive a sensory absence is not so straightforward. The brain’s sensory systems are geared towards detecting the presence of objects, rather than their absence: when an object encroaches on your visual field, generally speaking, neurons in your visual cortex are activated. Moreover, this bias towards detecting objects has been reflected in scientific interest in the topic: most neuroscientific investigations of perception and consciousness are interested in how we become aware of something. Despite this, experiences of absence make up a significant portion of our conscious experience – we often become aware of what we can’t see. Revealing their neural basis is just as important for fully understanding the mechanisms supporting human awareness.

Much like the delayed onset of fluency with zero, perceiving sensory absences also develops later in childhood, compared with the perception of tangible features. Classic evidence for this comes from the ‘feature positive effect’, which describes how a presence of something is easier to detect than its absence. For example, when four-month-olds are familiarised with the letter ‘F’, they will be surprised when the next symbol to appear is an ‘E’, which has an extra stroke at the bottom. But when the order is reversed and a familiar ‘E’ is followed by an ‘F’, the children are not fazed – it’s as if the absence of the lower line is simply not registered. Intriguingly, this parallels the inability of infants to recognise zero in the puppet experiments described earlier.

Our disadvantage for detecting absences is not something we’re typically aware of

Just like zero, our difficulties with perceiving absences don’t stop in adulthood. When proofreading written work, people are much better at detecting when letters have features added than when they’re removed (‘ONCE’ written as ‘ONGE’ will be easily spotted, but ‘STRANGER’ written as ‘STRANCER’ might not). When adults are shown image sequences, they also display similar ‘feature positive’ biases as children. This finding is robust across an array of auditory and visual stimuli, as well as across animals including pigeons, rats, honeybees and monkeys, suggesting that the detection of absences holds a consistently disadvantaged status among naturally evolved perceptual systems.

Not only this, but our disadvantage for detecting absences is not something we’re typically aware of. When we say we didn’t see something, we’re usually less confident than when we think we did see something, but we’re also worse at identifying when these judgments of absence are likely to be correct or incorrect. In short, it’s harder to have self-reflective insight into our experiences of absence than our experiences of presence.

If the way the brain supports the perception of absences is so distinct, how exactly does it generate these experiences of nothingness? Like with zero, emerging evidence suggests that certain neurons in the brains of birds, monkeys and humans are tuned to the experience of perceptual absences. In tasks where corvids and macaques were asked to detect whether a faint stimulus was shown on a screen, neurons in regions roughly analogous to the frontal cortex in humans became active just before the animals indicated they had not seen anything. Similarly, in humans, single neurons in the parietal cortex specifically fired when participants decided a vibration-stimulus applied to their wrist was absent.

Do these ‘absence neurons’ indicate that a person has already decided that a stimulus was absent, or are they contributing to the very process of making this kind of decision? We don’t yet know. Nonetheless, it seems clearer now that perceptions of absence are not mediated by a mere absence of neural activity. Instead, the brain may have unique mechanisms through which it represents these distinctive experiences.

The brain must be able to tell if our attention systems were alert enough to detect the object if it were present

Such mechanisms are central to some newly emerging theories of consciousness. These models, such as the perceptual reality monitoring (PRM) and higher-order state space (HOSS) theories, specifically focus on brain processes that decide whether something has been seen or not. According to these theories, there is a neural mechanism that interprets the brain activity found in visual (and other sensory) areas, a bit like a fact-checker. This mechanism checks whether the sensory activity contains enough reliable patterns to indicate you’ve perceived an object in the external world – or alternatively whether it’s noise, or mental imagery. Importantly, however, this system is not simply inactive when there is an absence of reliable activity in sensory regions. Instead, these theories claim the checking mechanism actively indicates that nothing has been perceived. This would explain how we can become aware of an absence of stimulation.

So how exactly do we perceive absences when there’s nothing out there to perceive? In a framework developed by the cognitive neuroscientist Matan Mazor, to be able to perceive an absence, we must first undergo some form of counterfactual reasoning such as ‘If the object was present, I would have seen it.’ What’s intriguing about this formulation is it requires access to self-knowledge regarding one’s own perceptual system: the brain must be able to tell whether it’s functioning normally, and if our attention systems were alert enough to detect the object or sound in question if it were present. There is empirical evidence to suggest this is the case. In a clever study, participants were asked if there was a letter embedded in noise: once their view of the noisy images was obscured using occluding lines, participants increased the rate at which they decided a letter was there when it was not. In other words, people were using the self-reflective insight that their visual system would be hindered in detecting the letter, and accounting for this in their decision-making.

All of this returns us to zero. The question is, does the same underlying neural mechanism drive experiences of both zero and perceptual absence? If it does, this would show us that, when we’re engaged in mathematics using zero, we’re also invoking a more fundamental and automatic cognitive system – one that is, for instance, responsible for detecting an absence of birds when I’m birdwatching.

The brain systems used to extract positive numbers from the environment are relatively well understood. Parts of the parietal cortex have evolved to represent the number of ‘things’ in our environment while stripping away information of what those ‘things’ are. This system would simply indicate ‘four’ if I saw four owls, for example. It is thought to be central to learning the structure of our environment. If the neural systems that govern our ability to decide if we consciously see something or not were found to rely on this same mechanism, it would help theories like HOSS and PRM get a handle on how exactly this ability arises. Perhaps, just as this system learns the structure and regularities of our environment, it also learns the structure of our brain’s sensory activity to help determine when we have seen something. This is what PRM and HOSS already predict, but grounding the theories in established ideas about how the brain works may provide them with a stronger foothold in explaining the precise mechanisms that allow us to become aware of the world.

An intriguing hypothesis inspired by the ideas above is that, if the brain basis of zero relies on the kinds of absence-related neural mechanisms that the above frameworks take to be necessary for conscious experience, then for any organism to successfully employ the concept of zero, it might first need to be perceptually conscious. This would mean that understanding zero could act as a marker for consciousness. Given that even honeybees have been shown to enjoy a rudimentary concept of zero, this may seem – at least to some – far fetched. Nonetheless, it seems attractive to suggest that the similarities between numerical and perceptual absences could help reveal the neural basis of not only experiences of absence but conscious awareness more broadly. Jean-Paul Sartre testified that nothingness was at the heart of being, after all.

The evolution of the number zero helped unlock the secrets of the cosmos. It remains to be seen whether it can help to unpick the mysteries of the mind. For now, studying it has at least led to less disappointment about my birdwatching failures. Now I know that there’s great complexity in seeing nothing and that, more importantly, nothing really matters.