Mind-body programmes are having their day. Controlled trials showing the health benefits of techniques like mindfulness-based stress reduction, yoga, tai chi, mantra and their variants have gained a respectable face in mainstream medicine. Reviews show prompt and lasting reductions in worry and stress, anxiety, depression, chronic pain and addictive behaviours across a broad demographic. Practitioners also report improved quality of life when these techniques are used as adjuncts to treatments for diseases like asthma, irritable bowel syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Sophisticated assays and imaging also show positive biological and structural changes accompanying these programmes. And the requirement of in-person attendance that once limited their accessibility has now been eased by online availability.

An added benefit is that mind-body techniques invest people facing health challenges with responsibility for themselves – an expectation that may be rare for the unwell. Getting better is assumed to be the health system’s responsibility. But even as the provider recommends changes we could make to improve our health and wellbeing, they recognise that we are unlikely to consistently follow through. Feeling anxious? Take these pills. It’s a passivity that appears to suit most of us, even as we may grumble about delivery and outcomes.

Mind-body programmes turn accountability around. The treatments, if you can call them that, require active engagement: becoming curious about our everyday behaviours and reactions to those we love, to food, to discomfort, and to how we respond to changes in our symptoms. There’s a bit of a libertarian ethos; it’s your mind and your body, and you’re often the best one to understand and adapt it. That sort of interest is central in reducing the distress and pain, and feeling more in control of symptoms.

But stress, chronic worry and pain – not diagnosable disease – are what bring most people to these trainings. Knowing that your cortisol rhythms might shift, or that your insula – the brain’s hub for sensing the body’s internal state – may become more attuned, might justify showing up. Yet it’s not that kind of knowledge that brings peace of mind. What does is becoming aware of the processes that keep us ill at ease. That’s where insight and change begin.

This is also what makes the work holistic. Not because it evokes the mystical, but because of the recognition that the mind and body are not separate systems – they’re an integrally woven net. The brain, for example, is interlaced with the rest of the body through constant loops of neural, hormonal and immune signalling. But our instruments can’t fully capture these loops. So we partition the organism, and study what’s available and measurable. That’s not a flaw in the science – it’s a feature. But it shapes our approach and the questions we ask, and it tempts us to trade the old mind-body divide for a newer, brain-body one.

While it holds great advantages, a scientific lens directs interest and curiosity away from lived experience. To close that gap, we need more than maps of circuits – we need to understand something of what the system has evolved to accomplish. And in that spirit, I’ll share what I’ve learned about the mind’s operating system through 50 years of mind-body practice and two decades of observing and listening to people in my classes and clinical trials as it relates to the anxiety of being human. It’s my best attempt at describing the default mental processes that leave us prone to worry in the first place – and how these mindfulness programmes help us recognise and gently shift the default processes that feed everyday distress.

Mind-body training is a phenomenological examination of our internal life to better understand and regulate it

For though mind-body activities such as meditation, yoga, relaxation or prayer may appear to be different, I’ve found they bring shared psychological processes to the problem of mental distress.

Just what do these programmes train in the mind and body? It turns out to be a kind of phenomenological research that each practitioner conducts on themselves. We understand ourselves in the everyday world through our mental life, and mind-body training is inner research, a phenomenological examination of our internal life to better understand and regulate it.

The training starts by bringing curiosity and awareness to our everyday thoughts, feelings and sensations so that we are both in the experience and closely observing it. In the process, we start to recognise elements of our experience so familiar that they’ve become invisible to us, even as they are shaping our experience of the world.

That’s the foundation. Recognition brings both immediate knowledge and a capacity for control. And people take it as far as it suits them. Asked how the practice helps, individual responses will vary along some version of: ‘It helps me relax, listen and feel more resilient in the face of uncertainty and/or pain.’

So what’s really going on? It comes down to psychology. Meditation means setting aside some time to observe your internal experience. Traditions differ in how that’s best done but, at its core, it involves witnessing the thoughts, sensations and feelings that coalesce to form the narrative that normally preoccupies attention. It’s a simple deconstruct that shifts interest from the stories and their emotional pull to the components that give rise to them. Instead of being swept away by the current, you begin to become curious about the water.

You begin to recognise that thoughts and feelings are events, that they come and go. And in that recognition, something shifts: not the thoughts themselves, but your relationship to them. They begin to lose their grip on attention. And in that loosening, space opens – for steadiness, for perspective and, sometimes, for stillness and peace.

The very familiarity of our mind and body can make any attempt at objectivity challenging. That’s why we call it practice. Prosaic thoughts are easily recognised as such, but charged ones take more patience as they repeatedly seize our attention. Still, interest gradually begins to shift from their content to the act of observation, like watching traffic pass. Just that shift brings its own kind of relief and, for many, it’s enough.

Monitoring your mind-body in this way also brings insights into its evolved operating system. You notice how, despite resolving to focus on your breathing, attention keeps returning again and again to the voice in your head. The one we usually refer to as ‘I’. You may notice also that the voice has recurring concern for the same themes: family and friends, health, work, sex and money – and the people and circumstances that might support or threaten them.

Preoccupation with what might go wrong leaves arousal chronically elevated and adversely affects our health

That’s because this persistent voice isn’t random – it’s purposeful. The human mind evolved to simulate scenarios, anticipate outcomes and solve problems before they happen. This astonishing capacity to imagine and communicate complex pasts and futures – where our physical and social needs are met – was an evolutionary triumph. Emerging awareness of cognitions may have enabled ever more complex plans: for the hunt, the raid, the trade, for safety, for loyal allies, for empathy and awareness of the inevitability of death.

For vulnerable hominids, planning and reviewing are the evolutionary priority. Similarly, needs for relationship, status and control keep a semi-vigilant narrative running for much of the day, making our bodies tense and ill at ease. And while a healthy and meaningful life depends on navigating the challenges and opportunities that planning presents, preoccupation with what might go wrong leaves arousal chronically elevated and adversely affects our health.

Of course, we don’t come into the world preoccupied and worrying like this. We arrive as little sensate creatures, curious and awake to the wonder of touching, tasting, hearing, seeing, moving, and their pleasant or unpleasant feeling tones. Feeling our way into the delicate social maze, pasts and futures became imperceptibly interwoven with thought and language; the naming and appraisal enabling us to describe our needs and impressions to others. And because our designs must cohere with the external world, we’re empirical creatures from the start, tossing food from our highchair, curious to see what happens to both the food and the people around us.

That emerging cognitive narrative becomes indiscernibly woven into perception, filtering the sensory world through its hopes, comparisons, judgments and disappointments. And it gradually becomes central to our developing sense of self: the story of ‘me’, who I am. When it’s down, so am I.

Powerless to control pesky thoughts, we go for experiences that divert attention from them. Something like eating is sufficiently pleasant to redirect attention back to sensations and the quick relief from tension that follows. The downside is that many such strategies lead to adverse health or social consequences.

These drifting thoughts are linked to a network in the brain called the default mode network (DMN). It’s most active when our attention is wandering to generate daydreams, memories and imagined conversations. It decreases when we are occupied with a specific task. People also report feeling happier at those times; recall those moments of flow, when your attention was effortlessly absorbed in what you were doing.

Sometimes, this wandering is creative or soothing. But it also loops through self-referential themes – what others think of us, what went wrong, what might go wrong next. When overactive, it can drive anxiety and rumination. That’s why people often report feeling happier when attention is less self-referential and fully immersed in the demands of a task. In those moments of flow, you’re effortlessly absorbed in what you’re doing and time seems to dissolve.

Meditative practices train this kind of attending. With repetition, they loosen attention’s default preoccupation with the mental chatter, leaving everyday awareness more open to that long-forgotten sensate world.

Getting there often begins with a simple step: noticing what your attention is on. Most of the time, it’s that internal narrative – the voice in your head, spinning stories or running commentary. The practice starts with noticing that voice and gently redirecting your attention to something emotionally neutral.

The breath is a common choice. Specifically, the sensations in your chest or belly as they rise and fall with each breath. There’s nothing mystical about this – it’s just practical. What you attend to drives your level of arousal, and the breath is consistently neutral in emotional tone, always available, and easy to feel. Try it for a minute: shift attention to the sensations of your breath. You don’t need to change or regulate your breath, just see what happens when the focus moves from the noise of the thoughts to those bodily sensations. The directive may seem straightforward, but you’ll notice that attention doesn’t stay there. Rather, it defaults back to that more primal, needs-serving narrative. But if you gently persist, those neutral breathing sensations replace the more vigilant narrative in attention, and your mind and body naturally begin to let go.

If you find that helpful, you can take it a bit further.

Meditation takes advantage of a simple deconstruct: our everyday experience is made up of thoughts, body sensations, and the feeling tone that accompanies them – how pleasant or unpleasant they feel. While normally tangled together, in meditation practice we separate them out and notice each one on its own.

Instead of wrestling with the monologue, you begin to recognise the connections shaping our rhythms and blues

One technique to assist this is to label them mentally. When something comes up in your awareness, you can quietly name it. For example, ‘thinking’ for a thought, ‘tightness’ or ‘coolness’ for a sensation, ‘pleasantness’/‘unpleasantness’ for their feeling tone. What we normally refer to as emotions such as sadness or anger are approached in a similar way: as suites comprised of thoughts, sensations and feelings. The labels we use don’t need to be exact. Just shifting interest in this way from the global experience to these distinct threads within that flow gives you a foothold in what often seems like a seamless blur.

This small shift – from focusing on what the content is about to noticing what kind of event it is – can interrupt the emotional pull of the story. It helps you start to recognise that these are mental events happening in awareness, not the totality of who you are.

These simple shifts reset the arousal system. Instead of wrestling with the monologue, you begin to recognise the rapid, usually missed connections shaping our rhythms and blues. With attention no longer automatically preoccupied with the internal talk, anxiety and stress levels naturally go down, and our less-filtered senses are once again fresh to life’s immediacy.

Sitting alone like this may seem strange for a species as relentlessly social as ours. But, as with turning the other cheek, Buddhism also encourages the non-instinctive. When we shift attention away from its usual default fixation on constructed pasts and imagined futures, we begin to recognise the constructed nature of much of what we experience as ourselves.

What we observe is not just random – it’s nature, structured to support the survival of tribal primates. The scope and complexity of these phantom imperatives emerging from biology was something truly new in nature and changed how we relate to the world.

The interwoven and tangled needs these processes serve echo through gossip, art, literature, politics and history. And because we cannot recall life without them, they become the mental water we swim in – unnoticed, yet shaping everything.

These recognitions can reveal truths beyond these everyday structures: the sense of a fixed identity; the idea of beginnings and ends, that we could have acted differently; the impression that our thoughts exist outside nature. We see also that its needs-based function makes the internal narrative naturally self-serving. In these glimpses, we begin to see – clearly, quietly, and perhaps for the first time.

For psychologists and other practitioners, mind-body research often begins in personal experience. Just as pain and stress bring most clients and patients to these programmes, similar personal challenges are what initially motivate most clinicians and scientists who use or study the techniques. We mostly didn’t get it from our clinical training. Finding personal benefit, some began integrating it into their clinical work. A few, curious as to how it works, started research projects that began to produce those clinical trial outcomes.

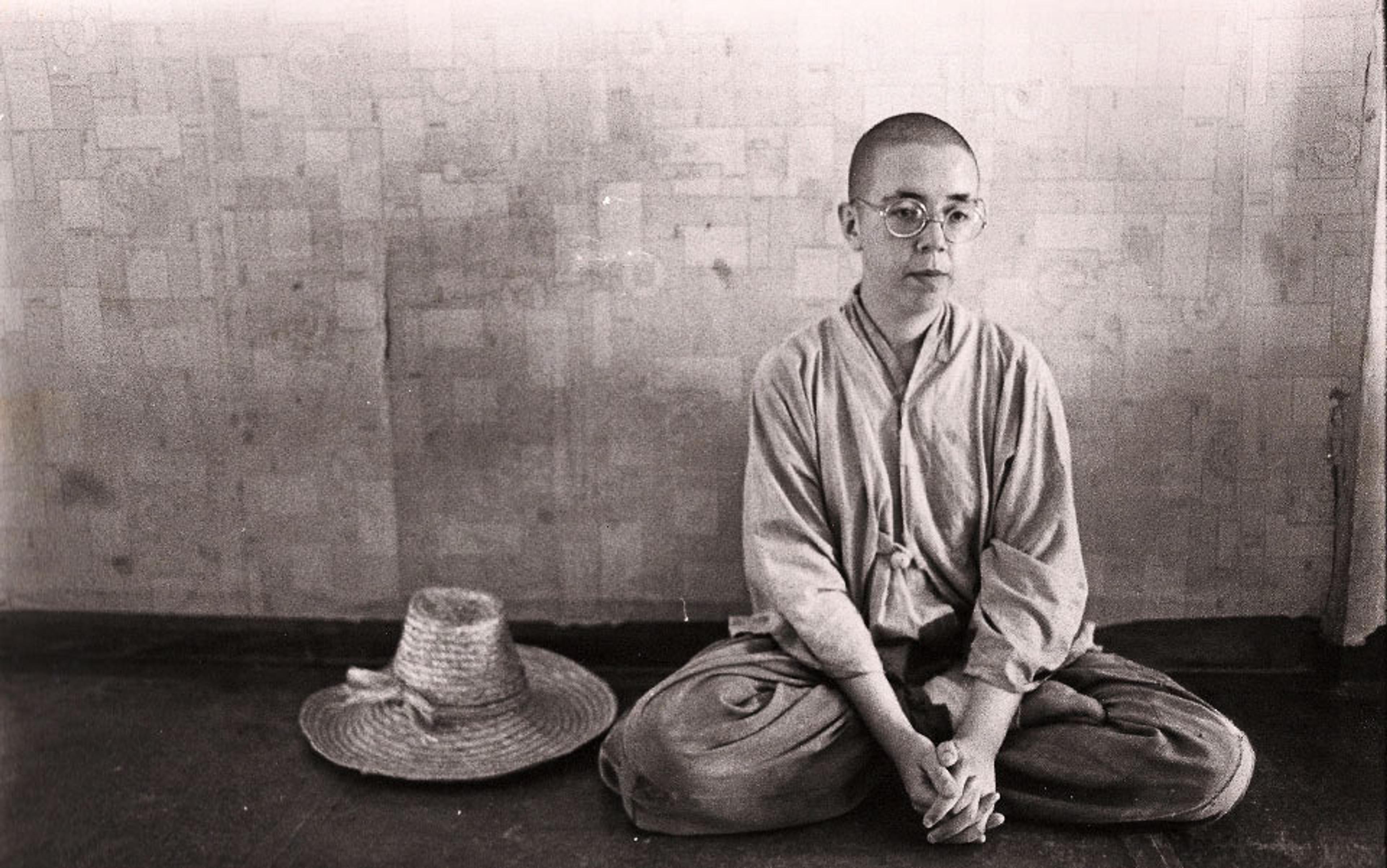

The early explorations were frequently in the context of the spiritual tradition the activity was part of. And the origins of those lie mostly in Asian contemplative traditions investigating the nature of the self.

Like many others, I came to this work not through theory, but through necessity. I didn’t attend my PhD graduation. I was in bed depressed. Growing up in darkness, I’d made it to university through dumb luck and New Zealand’s willingness in the 1960s to offer second chances. Now, with some sort of imprimatur and starting an academic psychology job, my internal state was testament to how little of real value I had to impart.

I should have sought therapy. But it was the early 1970s, and psychedelics promised speedy enlightenment. The prospect of relief from all suffering without having to dig around in the dirt was more than alluring, and I went for it wholeheartedly. But a nightmare LSD trip that ended in the ER made me consider gentler, ‘Eastern’ approaches. That led to a couple of decades traipsing through Asia and the United States studying, and practising in, the three main Buddhist traditions, Advaita contemplative practice, and yoga.

What finally helped with those deeper wounds wasn’t meditation, but therapy

The quality of instruction I found varied wildly. Some teachers seemed only a little less confused than I was; the worst were charlatans and destroyers of lives. But I stumbled across a few exemplars whose generosity and wisdom helped unwrap the layers. And something started to shift. The panic attacks I’d sweated through since that bad LSD trip stopped. Rumination was replaced by more open curiosity and a lightness of body and mind.

But meditation isn’t a cure-all. It couldn’t bring back the people I’d lost, or undo the confusion and pain of a childhood spent in darkness. Believe me, I tried. What finally helped with those deeper wounds wasn’t meditation, but therapy. Therapy helped to expose and unravel the conflicts embedded in that narrative I was still living out without realising it, surfacing the gaps and contradictions so they could loosen their hold on attention. It also helped me recognise that, even in its messiest moments, the mental narrative had been trying to help me, all along – like a well-meaning friend who doesn’t always get it right, but never stops showing up.

And meditation isn’t for everyone. Introspection doesn’t come naturally to many of us – especially in a culture that prizes action over reflection. Add to that the sometimes exoticised or esoteric portrayals of meditative practices such as yoga, tai chi and others, and it’s easy to see why some people write them off as too ‘fringey’. But even for those who are open, caution can be important – particularly for people in fragile mental states. Turning inward can surface painful memories or emotional overwhelm that may be hard to manage without support.

Stripping mindfulness down to its mental arms and legs like this, its basic mechanisms, may seem a bit cold. Some prefer that the poetry of transcendence and Buddhism’s ethical principles be integrated into their meditation instructions. But clinicians need a conceptual frame from which they can adapt mind-body principles to the circumstances and temperament of each individual patient. As a practical person myself, it’s the kind of framework I wish I’d been given five decades ago.

That may be the clinical framework – but what unfolds in practice is something else entirely. You might think of it as a right-brain approach to the ineffable. Even a little practice reveals something deeper: the quiet, spacious awareness in which our thoughts and stories arise, the transcendent qualities of the silent presence in which the narrative appears. It’s what some call the eternal now – the still, grateful point of the turning world, where only poetry will do. But that’s a theme for another time.