To tap into the flow state, your skill level and the challenge of the task you’re working on should be in perfect balance. This is one of the eight principles of flow, first described by the Hungarian scientist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. He coined the term ‘flow’ in 1990 after decades of scientific work about what surgeons, painters, dancers, writers, scientists, martial artists, musicians and other creatives have in common – a curious, all-absorbing state of mind where we feel amazing and are incredibly productive and creative at the same time.

Modern neuroscience distinguishes between two mental states: one of striving, where a surge of dopamine keeps us laser-focused on external goals like winning, perfection or achievement – and another of serene presence, where we hover in the moment, simply being. In this latter state, our neural chemistry shifts; endogenous opioids and endocannabinoids fill the brain, bringing feelings of deep satisfaction, fulfilment and joy in the now.

Motivation psychologists distinguish these two states as extrinsic and intrinsic motivation for what we’re doing. The former takes hard work and discipline to keep us going. The latter propels us forward, as by magic: flow. Research even shows that those more prone to enter the flow state might have lower risk of mental health problems and cardiovascular disease.

The more we read about flow or hear people describe what it feels like, the more we want to be in this state regularly. And we should – according to science! However, for most people, flow is something they might remember from childhood, when they were lost in play. Or it is something that may happen by chance but is incredibly hard to tap into at will.

The Romantic myth of the creatively engrossed genius also doesn’t help us. The human mind loves a hero’s story, and most of us seem to know what we were doing and why, in retrospect. Clearly, the thought leaders and architects of human history just ‘had it’, that creative ability to flow. Gutenberg’s printing press started off exponential literacy development. Electricity, vaccines and antibiotics brought about unparalleled social changes and health and wellbeing enhancements. The Lumière brothers moved people in 1895 with the first-ever movie. Fairy-tales, paintings, musical pieces and dances by known and unknown artists keep enthusing brains all over the world. Accounts of how one person’s creative flow leads to excellence, societal impact and Nobel prizes wow us.

It seems there’s nothing left for the rest of us mere mortals but to be bystanders to others’ brilliance. The more we read about the gifted, the more we feel blocked and barred from heightened creativity and the promise of the flow state ourselves. Who could ever keep up with Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity? Yet Einstein failed his university entrance exams in language and history, and he’d been broke and unemployed. The myth of the genius is that these individuals woke up one morning and excelled. As a result, too many people are convinced that either you’re creative and you just happen to be able to find flow, or you’re not and you don’t.

Once you grasp what sharpens our talent for brilliance, you’ll realise that flow is for everyone

What is never mentioned about the grand inventors, artists, scientists and doctors of our world who have done amazing deeds for humanity with their minds and hands is that they all failed in their attempts before they made it.

Besides failure, the second mysterious ingredient that made them brilliant in the first place and allowed them to wake up one morning and let their intuitive mind make ‘the splash’ is also never mentioned. Once you grasp what sharpens our talent for brilliance, and how to get it, you’ll realise that flow and creativity is for everyone.

But beware – the path to flow is paved with more bad advice.

‘You just have to feel it,’ our drawing teacher Carlo used to tell us, over and again.

It looked easy when he let his charcoal slide over the textured surface of the cold-pressed paper, his trace revealing shapes, intentions and emotions in 3D. It looked so effortless, and he looked so pretty, immersed as he was. Then he’d resurface and his facial expression would transform into an exhausted frown at our botched attempts to feel with a pen on paper. No matter how hard I’d tried, the feeling somehow didn’t stick to my pencil – and, after a while, I didn’t stick to the drawing classes either.

Flow is a fleeting, immersive state in which time and space seem to compress or expand, accompanied by a delicious fusion of movement and awareness – where you don’t just move: you are the movement. You have a very clear goal of what you’re trying to achieve. You know what you’re doing. You’re receiving clear feedback from the task itself about how it’s going, and you know when you’re doing it right. You’re also feeling intrinsically motivated to keep going, and the noise of uncertainty fades, leaving you feeling in control of your life and free from ruminative thought loops. All the while, Csikszentmihalyi’s core principle of matching the challenge to your skill makes you hover in this sweet spot, where what you’re doing is neither too hard nor too easy. Altogether, these dynamics form the eight core principles of flow.

Years ago, without any scientific training at all – when I was still a professional dancer, before the injury that ended it all – I knew this feeling well. I used to tap into it regularly. Especially when I was away from the competitive life of a professional dancer, far away from the classical music and the pointe shoes. At home in the kitchen dancing to Michael Jackson, or in some techno club at night, where I hid in a too-large hoodie and no one knew me. There, I could feel it and, like my drawing teacher Carlo, I couldn’t understand why others couldn’t just feel this way too.

It was so easy and it made life’s pressures recede into the shadows, letting me live.

Today, I’m a neuroscientist. I’ve since found flow in science, while writing fiction, dancing Argentine tango, belly dancing, reading – and one strange afternoon, I also finally found flow with drawing. Thanks to the knowledge about the brain that I have now, I know that just ‘feeling it’ is by no means enough to excel, be creative, nor to find flow. ‘Feel it!’ is well-meaning advice often given by artists, scientists and other professionals. I’m guilty of having shouted ‘Feel it!’ to bewildered dance students too.

The real control centre is in the brain. This is where movement begins

What we creatives are often unaware of is that talent isn’t everything. Sure, talent helps – but just as important is something else we rarely think about: repetition. The repeated movements of our craft – the physical routines we practise over and over – follow us everywhere. Whether we call it practice or technique, these repeated actions shape our brains in powerful ways, often without us even realising it.

They form unique connections in the brain – linking movement, memory and emotion. These connections stretch across the parts of the brain that control movement, wrap around the areas responsible for memory, and reach deep into the emotional core of the brain – the limbic system. That includes the insula, a region that helps manage both our physical health and our inner sense of self.

‘Muscle memory’ doesn’t live in our hands or legs. The real control centre is in the brain. This is where movement begins, guided by systems that plan and initiate what we do. From there, messages travel through long chains of nerve cells – from the brain down the spine and out to the rest of the body. Millions of tiny electrical signals, known as action potentials, move back and forth, telling our muscles, organs and even the tips of our fingers what to do next.

The idea is to ‘program’ the right moves in our brain so they become so automatic we can use them to, yes, feel, and to find flow.

One thing is for sure, if you keep chasing flow by some sort of celestial action, waiting for your inner genius to strike from nowhere, you’ll keep failing. Because that genius, apologies for being blunt, is, in fact, nowhere to be found. Genius is work.

Enter your new superpower: knowledge from neuroscience.

What may seem a strange, repetitive, even boring activity is in fact doing magic to their brains

The prefrontal cortex sits behind the forehead and is one of the youngest parts of the brain, in evolutionary terms. In other words, this is a system that evolved late in our species’ development and is thus fairly unique to humans. It also happens to mature last in our individual development, with restructuring continuing well into our 20s.

These parts of the brain are very ‘plastic’, meaning that they are easily shaped by experience and learning. So they are also key to the development of technique in our craft – be that in science, the arts or other fields – because they are suited to rule-based learning.

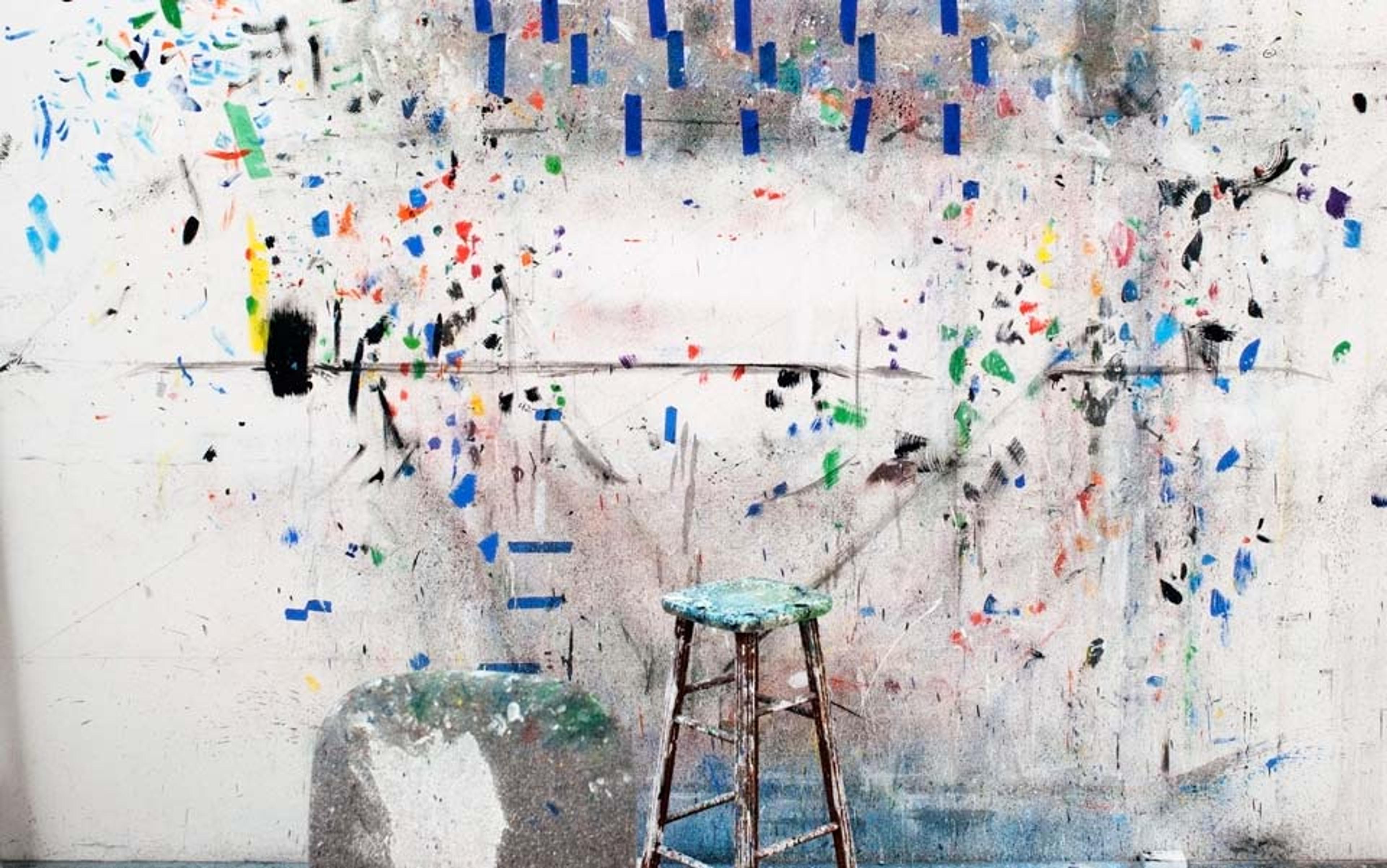

Neuroplasticity is our brain’s capacity to learn; to forge new connections between neural systems, as we practise something with our body. Professional singers and actors do daily vocal exercises, dancers do daily barre exercises – the same moves over and again – and musicians are known for their neverending scales practice that drives neighbours up the wall. What may seem a strange, repetitive, even boring activity that artists, scientists and other creatives engage in daily is in fact doing magic to their brains.

Repeating something consciously – in this context meaning exercising those prefrontal systems of the brain – is quite effortful, and it needs a lot of energy and attentional resources. Therefore, our brain starts to forge connections that let the movements we’re practising pass from explicit, effortful memory systems into implicit, almost automatic memory systems.

The Romantic painter J M W Turner, well known for his wild seascapes, continued attending life-drawing classes at the Royal Academy where he’d been a student, to practise the basic moves of his craft. In so doing, he kept exercising the fine motor skill needed to draw. Slowly, connections were made between different neural systems; Turner’s skill was powered not only by explicit, effortful connections of the prefrontal systems but also, ultimately, by implicit, procedural memory systems and enabled flow.

To investigate the contribution to creative expression of those rule-loving prefrontal systems and the deeper, feeling-based systems, a team of researchers from Drexel University in Philadelphia invited two groups of jazz musicians – one made up of novices, the other, of professional jazz musicians – to a brain-stimulation experiment. Jazz musicians are known to pour their heart into their strings in spectacular improv sessions, ‘feeling it’ and finding flow. In the experiment at Drexel University, transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) was used to introduce a little extra electric energy, via a coil held close to the brain, into the prefrontal systems of the musicians while they were playing.

Now – remember what you now know about the brains of experts. Regular technique practice allows us to tap into our skill, without having to think about it, because the skill has passed into implicit procedural memory systems in our brain. What do you think will happen if we now introduce extra energy into experts’ prefrontal systems?

Creatives who invite regular technique practice into their life will experience their art as second nature

Results showed that introducing extra energy into the rule-based systems pulled experts away from their intuitive expression. They performed worse. In contrast, the novices’ performance improved under this treatment. Clearly, the novices were still relying on those rule-based, logical brain systems to perform ‘correctly’ – therefore, introducing more energy into these systems helped them with their performance.

This works a bit like learning a new language. First, we learn the words, the basic grammar, and we make many mistakes. It is effortful and we have to think before uttering any sentence at all. But as we repeat the words, practise verbal tenses and vocabulary over and over, our brain realises the repetition and transports the skill of that new language from explicit to implicit memory systems. That’s when we start to express and create entire new sentences with that new language: one fine day, you may even understand a poem in that new language. Creatives who invite regular technique practice into their life will experience their art as second nature and a means to expression.

‘Talent’ is never enough for true brilliance. You do need technique practice to forge the right pathways in your brain.

That’s why the advice to ‘just let go’, ‘be in the present’ and ‘feel it’ are unhelpful to find flow. When flow happens to you, it may well feel magical, it might feel like you’re ‘letting go’. You feel a strange fusion of your movements and your awareness, and you’re somehow entirely enwrapped in the present. It’s still early days to say exactly how this works, but it has to do with those low-level, implicit memory systems that encode movements that we internalise with technique practice. Then, the prefrontal systems deactivate while we let the implicit motor memory systems do their job. That’s when you use that skill to express and find flow.

But this is a neural process that happens outside of your conscious awareness, you can’t do this at will.

If you’re able to write and read, you already have one potential flow tool at your disposal: you no longer have to think about writing a word, or deciphering my writing, letter by letter, as you read. Your writing and reading skills are firmly anchored in your implicit memory systems and you can effortlessly use them to express and to find flow. Many people experience flow while reading a book, as research led by Birte A K Thissen shows. And decades of biopsychological research by James Pennebaker and his team from the University of Texas at Austin has shown that expressive writing can lead to improvements in immune markers and wound healing, fewer doctor visits in a six-month follow-up period, and a lighter, happier mood overall. Expressive writing is a technique by which you write for some 15-20 minutes two to three times per week. While writing, you should focus on what you feel – and express that. Importantly, you should plan not to show what you write or create to anyone, due to the social injury risks of disclosure. Don’t, unless you know that the recipient of your vulnerable writing is worthy of your trust. Your flow-tool must be, and remain, your safe-space. Risk of hurt will root you firmly in the present and prevent you from finding flow.

How do we create a flow-tool for creative behaviours that we haven’t been using since mid-childhood, like reading and writing? Well, start with technique practice and copying. As scientists, we ask about the mechanism. Our brain creates habit-loops when it learns stuff. In neuroscientific terms, habits are action-based associations between a cue, an action and a reward.

The first step in achieving flow is understanding that the senses act as channels to the brain, then surrounding our senses with the right cues. For little time windows in our day, we should create cue-spaces that are conducive to flow. This means hearing, seeing, smelling, tasting and touching cues that will make our mind flow, including also maybe modifying the space we’re in (triggering our exteroception), the movements of our body (proprioception) and the feelings that rise to our awareness from within (eg, when what we eat, smell, etc trigger our interoception). As we repeat this experience, our brain forms conditioned neural links between these cues and the feeling of flow.

It’s like switching on your brain’s energy-saving autopilot

Of course, it isn’t as easy as that from a neuroscientific point of view, and there is a lot that we still don’t know. But, for argument’s sake, let’s imagine this process like a golden thread between a cue and a memory stored in your memory systems that sit safely tucked away behind your temples. Now, each time this cue emerges before your senses, it swings a little lasso and, through receptors all over your body (in your eyes, nose, skin, etc) and long ganglia (nerve cells) – its lasso reaches into your brain and hooks on to its very special knob within your memory systems. Then, the cue pulls at the knob, and your mind follows in the direction of the memory encoded there, and off you go, back into flow. Because that feeling was encoded with the memory of that cue, your mind already knows the way. This happens each time a pianist touches the keys of their piano, a painter sees their pigment, or a ballet dancer hears their practice music.

The trick is to turn these cues into what I call ‘pathway prompts’ – little signals that help your brain slip into flow mode naturally, without needing to think about it. It’s like switching on your brain’s energy-saving autopilot.

For my own writing habit, I rely on cues that appeal to my senses and trigger familiar rhythms in my brain. I write in the mornings, when my body feels sensitive from just waking up. I drink coffee – the taste, smell, warmth and sound all tune me in. I sit in a café – the buzz of the place grounds me. I write on a laptop I use only for writing – it’s familiar, and signals ‘It’s time to focus.’

That’s my writing cue-scape – a set of sensory triggers that gently steer me into flow.

What’s yours?

A certain level of mastery makes it easier to find flow with your activity. In neural terms, ‘mastery’ is when the skill starts passing into the implicit, procedural memory systems. This will trigger the ‘skills-challenge principle’, where your chosen activity is neither too easy, nor too hard, all the better to absorb your attention.

‘Aren’t you done learning all those dance movements yet, Julia?’ one grumpy uncle of mine once said, while he loaded up a huge piece of cake onto his plate. I nibbled at my carrot and smiled at him. The ceiling is unlimited, and you can always keep learning and improving your artistic skill. The secret is, you’ll never be ‘done’ learning to dance, draw, write, play an instrument. And thankfully so – with art at hand, you’ll never be bored, you’ll always have something new to learn, discover and conquer: a new move, a new aesthetic. That movement on repeat, which has become so much you with time and repetition, will always bring you back to you, to your wonderful self.

Identify a flow-tool that matches your need for stimulation. Give your brain a respite from the unpredictability of life

Besides, repetitive movement practices have a wonderful side-effect if used well: they remove uncertainty from our brain. Uncertainty is part of all our lives to a larger or lesser extent; and it is among the chief killers of our calm. Csikszentmihalyi stated that being in flow makes us escape from the unpredictability of life. Technique practice offers the space to start on that journey, because repetitive movements – as when we practise an artistic skill like drawing, dancing, music-making or knitting – are washing machines for minds. Life is unpredictable, and our senses can’t always find something recognisable to cling to. When our ability to predict is weakened and our brain is put on alert, this mind-absorbing state can make us feel miserable. We can regain our footing by controlling our surroundings or other people, but if flow is what we seek, we’ll fail. What we need instead are routines in our day to create habits of wellbeing in our mind, because our brain will, during those periods of routine, know exactly what’s going to happen next.

After a while, of course, routines are boring. That’s why I suggest we all identify a flow-tool that matches our need for stimulation too. With a creative practice that is right for you, you’ll be building the right movement habits in your brain to make your art your second nature so you can find expression. At the same time, you’ll also be giving your brain a respite from the unpredictability of life.

Place those pathway prompts strategically in your surroundings – and off you go, flow.