The 2020s have seen an explosion in rhetoric about mental health – about the importance of monitoring it, tending to it, talking about it. Public discourse had already been trending steadily in this direction for years, with celebrities increasingly sharing their own struggles with mental illness, and the number of Americans using psychological services rising steadily since at least 2010. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, phrases like ‘Everybody has mental health’ and ‘It’s OK not to be OK’ have started to feel less like platitudes and more like indispensable parts of the new normal. Driven by the rise of telehealth and a massive spike in anxiety and depression since 2020, there has been an increase in demand for behavioural health services across the board.

In recent years, the concept of a ‘mental health day’ has entered the popular lexicon, usually referring to a self-granted day off from work, school or other day-to-day responsibilities. This clues us in to the fact that, for significant parts of the world, ‘mental health’ is no longer simply defined in the negative – ie, as the absence of mental illness. It now also includes positive ideas about general wellbeing, emotional intelligence and self-knowledge, and a harmonious work-life balance. It is an idiom we use to understand, critique and evaluate the basic conditions of everyday life.

The tools and theories of mental health professionals have also made their way into the ordinary language that we use to understand many aspects of our lives. For example, it is now common to turn to therapy-inflected language to make sense of our relationships: the concepts of trauma and toxicity have become powerful explanatory tools for interpersonal conflict. A raft of psychiatric diagnoses – OCD, bipolar, BPD and ADHD, especially – are commonly used as self-descriptors with varying degrees of seriousness.

A bus stop advertisement in the eastern suburbs of Sydney. Photo supplied by the author

Corporations, nonprofits and government agencies now endorse good mental health in their promotional materials and public service announcements. We see mental health-themed advertising campaigns and sponsored nights at sporting events, billboards encouraging us to ‘fight the stigma’ or lend an ear to a friend who might be struggling privately. This trend becomes especially noticeable during each year’s Mental Health Awareness Day/Week/Month (the exact timing of which varies somewhat by country and organisation), in which some of the most recognisable brands participate. Walmart, Marks & Spencer, the All Blacks, Google and the Royal Bank of Canada have all created their own mental health charity partnerships and awareness campaigns for the occasion.

In 2021, the American football league (NFL) marked Mental Health Awareness Month by posting a series of short video testimonials in which players talk about the importance of maintaining both physical and psychological wellbeing (as Joey Bosa, a linebacker for the Los Angeles Chargers, said: ‘Your brain is a muscle, too’). In 2023, Starbucks published brief interviews with some of its employees who were most passionate about keeping mental health a top priority in the workplace (Kirsty, a store manager, said: ‘I lost a friend because of ill mental health. Having a support network inside of work [where] you feel safe is crucial’). This is typical of the way mental health discourse helps major organisations publicly affirm their commitment to kindness, neurodiversity and progressive social values.

Countless celebrities, musicians and athletes have shared their psychiatric diagnoses, becoming positive role models

In January 2024, the children’s TV show Sesame Street made headlines when its most famous spokesman enquired about the public’s mental health. The X post, which went viral, read: ‘Elmo is just checking in! How is everybody doing?’ Elmo’s social media post racked up hundreds of millions of views and tens of thousands of replies from seemingly desperate and frightened people. Amid the top responses to this bit of light engagement bait were serious expressions of economic anxiety, climate doom, intense loneliness and general political despair. In March, possibly in response to this high-profile display of public distress, the show’s parent organisation Sesame Workshop launched a partnership with the Ad Council to provide a host of emotional wellbeing resources for children and families.

The attention generated by these campaigns may or may not translate into concrete mental health resources, as it did in the case of Sesame Street. Often, their splashiness seems to eclipse the underlying message. An illustrative example here is Burger King’s #FeelYourWay campaign from May 2019. Tying into the theme of authentically expressing one’s feelings, customers were encouraged to order a ‘Real Meal’, that is, a Whopper in special packaging decorated to match the consumer’s mood at that time. In the words of the press release: ‘Burger King restaurants understands that no one is happy all the time.’ In contrast to their rival McDonald’s well-known ‘Happy Meal’, the campaign included options like ‘Pissed’, ‘Blue’, ‘DGAF’ (for ‘don’t give a fuck’), ‘Salty’ and ‘Yaaas’. Understandably, Burger King faced some criticism for this rather dubious connection to Mental Health Awareness Month.

Still, paying attention to these campaigns can tell us something important about our present moment. They all subscribe to the same, basically sound internal logic:

- Many people experiencing mental health issues like depression and anxiety suffer in silence.

- Simply talking about what is going on with someone else can significantly ease this burden.

- Encouraging such conversations can help people spot concerning signs like suicidality.

- Stigma, which prevents these interventions, is morally wrong and potentially deadly.

- People should feel unafraid to seek appropriate treatment or professional help.

- Small lifestyle adjustments like regular sleep and exercise will make many people feel better.

In Canada, the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom and Aotearoa/New Zealand, these tenets help form the basis of a (nominal) public consensus in polite society: that mental health is an indelible part of human health in total.

There are good reasons to celebrate these campaigns. They reflect the welcome reality that ‘psychic wellbeing matters’ is now a mainstream, even ‘neutral’ position. This recognition of the inherent goodness of mental health is the result of hard-won gains made over decades by the activists, scientists, artists and philosophers who together have transformed our understanding of the dark and frightening things of which all our psyches are capable.

Pioneering research in psychoanalysis identified the unconscious as a fundamental component of human being, demonstrating that we are all subject to alien, irrational and contradictory dynamics within ourselves. Decades of published research and case studies confirm that ‘neurodiversity’ is an essential part of our species’ natural variation – that suffering extremes of thought, feeling and behaviour are all relatively common, and that these tend to be disordered in ways that follow particular patterns, and which may respond to specific medications or therapeutic techniques. Those with lived experience of psychiatric violence have pushed the movement for disability justice to include both ‘users and refusers’ of the mental healthcare system, and forced society to reckon with the thorny question of involuntary commitment. Countless celebrities, musicians and athletes have shared their psychiatric diagnoses and become positive role models to everyday people who are similarly struggling.

For far better than for worse, someone in a rich country living in any kind of psychic pain today is much more likely to seek and to get help for it than their parents or grandparents were.

In his classic study Madness and Civilization (1961), the philosopher Michel Foucault shows that the supposedly more ‘enlightened’ and scientific idea of ‘mental illness’ (which came to replace the older concept of ‘madness’) also resulted in exquisite brutality for those who were deemed different. These legacies of shame, abuse, unjust institutionalisation, homelessness, excessive physical restraint, employment discrimination, neglect, stupefaction with powerful drugs, and disownment by family lasted well into the late 20th century and are still very much with us today. But something really has shifted in our own time: we now identify more with the figure who is different; the pathological position has become the default one. In this sense, ‘It’s OK not to be OK’ isn’t just a corporate slogan. It’s also a profound distillation of massive social change.

Foucault was greatly disturbed by modern psychiatry’s ability to draw definitive lines between the ‘reasonable’ and the ‘unreasonable’. He came to see it as another way for society to punish and marginalise its most troublesome subjects. Deploying the metaphor of a circulatory system, he conceived of psychiatrists as figures of ‘capillary’ power – unlike the conspicuous, beating heart of the state, these authorities functioned as more subtle, distal agents of the status quo. Writing in the 1960s and ’70s, Foucault saw the psychoanalytic therapists of his day as the latest technicians managing ‘one of the West’s most highly valued techniques for producing truth of one kind or another’ – the confession. This is the idea that disclosing one’s inner darkness leads to salvation, truth, self-actualisation. There is an important similarity between how this dynamic plays out in the church and the clinic: ‘bravely confront and share the ugly things inside you’ equally describes the task of the confessional booth as it does the therapist’s couch. In both cases, there is more at play here than simple unburdening: it is not just that ‘shared sorrow is half sorrow’, as in the case of confiding in a friend, but also that having an adversarial encounter with yourself can be fruitful in some way.

This uneasy brush with the self, mediated through a person with social authority, is an essential feature of these confessional practices, and distinguishes them from other kinds of dialogue. Therapy is based on this same model: it is carefully choreographed around a highly skilled worker, one with the practical knowledge and symbolic authority to endow this interaction with the gravity it deserves. We see this same idea articulated today when a therapist reminds their patients that their office is a ‘safe space’. In many countries, the law itself recognises the clinic as a place of privileged communication, subject to the strictest standards of medical confidentiality.

It seems that confession – in a broader and more literary sense – is a key social commandment of our time

Today’s mental health campaigns likewise try to capture this sense of security and special protection from reprisal, but with an additional challenge: they wish to project this ethic beyond the confines of the 50-minute session, into everyday conversations with friends, colleagues and loved ones. There are many initiatives whose names allude to this focus on ordinary dialogue as a form of intimate disclosure: there is ‘Seize the Awkward’ and ‘Talk Away the Dark’ (campaigns of the major mental health charities), ‘Make It OK’ and ‘Operation: Conversation’ (put on by regional healthcare providers), ‘Here to Hear You’ and ‘Ask Listen Talk Repeat’ (organised by local health departments), #ReachOut and #LiftTheWeight (campaigns of major professional sporting organisations), ‘I’m Listening’ and ‘Britain Get Talking’ (those of private broadcasting companies). Some are bespoke, such as ‘Walk the Talk’ (aimed at New Zealand youngsters), ‘Don’t Keep It Under Your Hat’ (for Aussie farmers), #YouAreNotAlone (for Norwich City FC supporters), and ‘Let’s Talk About It’ (for NBC News consumers in the catchment area of Greater Portland, Maine).

Through these sorts of programmes, it seems that confession – in a broader and more literary sense – is a key social commandment of our time. These campaigns and initiatives present being there for people as a duty to those who want to share what’s bottled up inside them, and doing the same yourself. In real ways, this affords us an unprecedented level of freedom of emotional expression. It reaffirms that even ordinary relationships are based on the most profoundly caring ethics.

But the campaigns make it less clear in whom we should locate the social authority necessary for these kinds of vulnerable interactions, in which we may encounter alien or delicate parts of ourselves. The campaigns blur the line between laity and expertise, between clinic and home, between therapist and friend. The already diffuse, ‘capillary’ power of the therapist has somehow become even more so, osmosing through the walls of the clinic. In neoliberal societies with mental healthcare systems buckling under the pressure of skyrocketing demand, this essentially conscripts everyday people as frontline healthcare workers with an unclear remit.

If we’re really going to heed the call to address this ocean of unmet psychic need, then we will need to stop mystifying who is meant to be doing what. There is an ambiguity in these campaigns about exactly what kind of conversation topic, or conversation partner, constitutes ‘getting help’.

Informal care relationships become the first line of defence against the worst possible psychiatric outcomes

On the one hand, this messaging clearly takes expertise seriously. It is common for such campaigns to direct the public towards relevant healthcare providers: emergency services, general practitioners and mental health specialists. This is known as ‘signposting’– using one’s own visual real estate to direct people to other services or organisations (eg, ‘If you are feeling suicidal, call this crisis line’). The effect is to highlight the necessity of the trained mental health professional, and to endorse the basic trustworthiness of those with credentials (social worker, psychologist, psychiatrist, etc). It endorses the formal tools of the ‘psy’ disciplines – structured therapeutic sessions, medication, hospitalisation when necessary – as fundamentally legitimate.

On the other hand, these campaigns also downplay the authority of the therapist. They stress the necessary everydayness of such conversations, and encourage the troubled person to confide in a close friend, family member or coworker. The informal, nonprofessional nature of these intimate conversations is evident in the marketing materials for these campaigns, which often feature text bubbles or other stylisations to hint at the casualness and ease of checking in. R U OK?, a prominent Australian anti-suicide charity, is exemplary in this regard. Premised on the idea that ‘a conversation could change a life’, the organisation places its eye-catching yellow-and-black signage all over public spaces. These ads encourage ordinary Australians to perform simple, routine check-ins with others they know, to help spot concerning signs of mental illness.

The organisation’s name, stylised in textspeak, alludes to the belief that life-saving conversations – ie, ones in which signs of suicidality or depression are spotted – can be easily and informally initiated. One ad campaign for the annual ‘R U OK? Day’ in 2011 featured the actor Hugh Jackman brandishing a tiny coffee cup with the organisation’s logo, referencing the fact that profound conversations about mental health can be had in unremarkable social settings, like over a (soft) drink. The organisation has continued to stress this link between routine sociality and psychological wellbeing. In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, the suicide prevention organisation ran an ad campaign that encouraged people to #stayconnected while locked down and social distancing. The implication is that informal care relationships are the first line of defence against the worst possible psychiatric outcomes.

I think that even the architects of these well-meaning campaigns would agree that, at a certain level of acuteness or severity, a person’s psychological problem passes from the realm of the everyday to the realm of the pathological. At that point, there should be a seamless handoff to an appropriate mental health professional.

So there remain some very important questions: who is fine just talking to friends and family, and who needs professional help? How does one know the difference? At what point does the conversation stop belonging in the social realm and enter the domain of the expert or professional? A tremendous amount of trust is put in the lay public’s ability to adjudicate this, calling into question both the upper bounds of intimate friendship and the lower bounds of mental healthcare.

R U OK?’s four-step, quick-start guide for these conversations hints at the tension between the normal and the pathological. Step 2, ‘Listen’, reminds the public that: ‘It’s important to remember that much of what people go through in life will be out of your control. You don’t need to “solve” or “fix” what they’re going through, and often you can’t. Just listening and helping them feel heard can go a long way.’ Step 3, ‘Encourage Action’, reads, in part: ‘If they are really struggling, encourage them to access professional support. You could offer to help them book an appointment with their GP or research some helplines. You can find a list of free 24/7 national support services at the link below.’

The question of who should actually get professional help is a grave one, and it raises structural issues beyond the scope of these campaigns. For example, booking an appointment with a GP (who may or may not be adequately trained in mental health issues) can take weeks in Australia, whose healthcare system faces a growing shortage of physicians due to chronic government underinvestment in Medicare, the country’s universal healthcare insurance scheme.

Minimal social expenditure for maximal labour productivity is still the order of the day

Mental health organisations in the UK, whose public health infrastructure suffers even more neglect than Australia’s, also fudge the important distinction between a good chat and a productive therapy session. In 2017, ‘Heads Together’, an initiative of the Royal Foundation of the Prince and Princess of Wales, launched a campaign called #OKtoSay, similar to those described above. In a promotional video for the campaign, Prince William, Princess Catherine and Prince Harry sit together at a picnic table in a bucolic outdoor setting for a candid-seeming chat about why mental health matters to them. Harry likens these ‘simple conversations’ to ‘almost like a form of medicine’. Kate repeats the line, recalling meeting ‘a young mother [who] said that to me … just talking to somebody, having those conversations, is like medicine for her. And that is the point.’

Of course, the royals were using a literary turn of phrase here, but the language matters and brings back the unresolved questions: are these simple conversations, no more intimidating than watercooler chat, or are they tantamount to a miniature therapy session in itself? If we consider this in light of the fact that the UK explicitly began publicly funding cognitive behavioural therapy to return the unemployed to work, then ‘talking to a friend is actually like treatment’ becomes potentially more sinister. Minimal social expenditure for maximal labour productivity is still the order of the day, so messaging from the ruling class hinting that a friend is as good as a doctor should at least make us raise an eyebrow.

In the absence of strong social bonds or comprehensive political programmes, Western governments and their corporate and nonprofit allies have collapsed the two into one half-measure: everyone is a therapist, and everyone is in therapy. The loud part – which says that intimate, honest conversation is good – masks the quiet part, which is that it’s also meant to serve as an adjunct to the state’s mental healthcare capacity. The result is that conversation may seem an end in itself, with no proper attention paid to the actual content of these interactions.

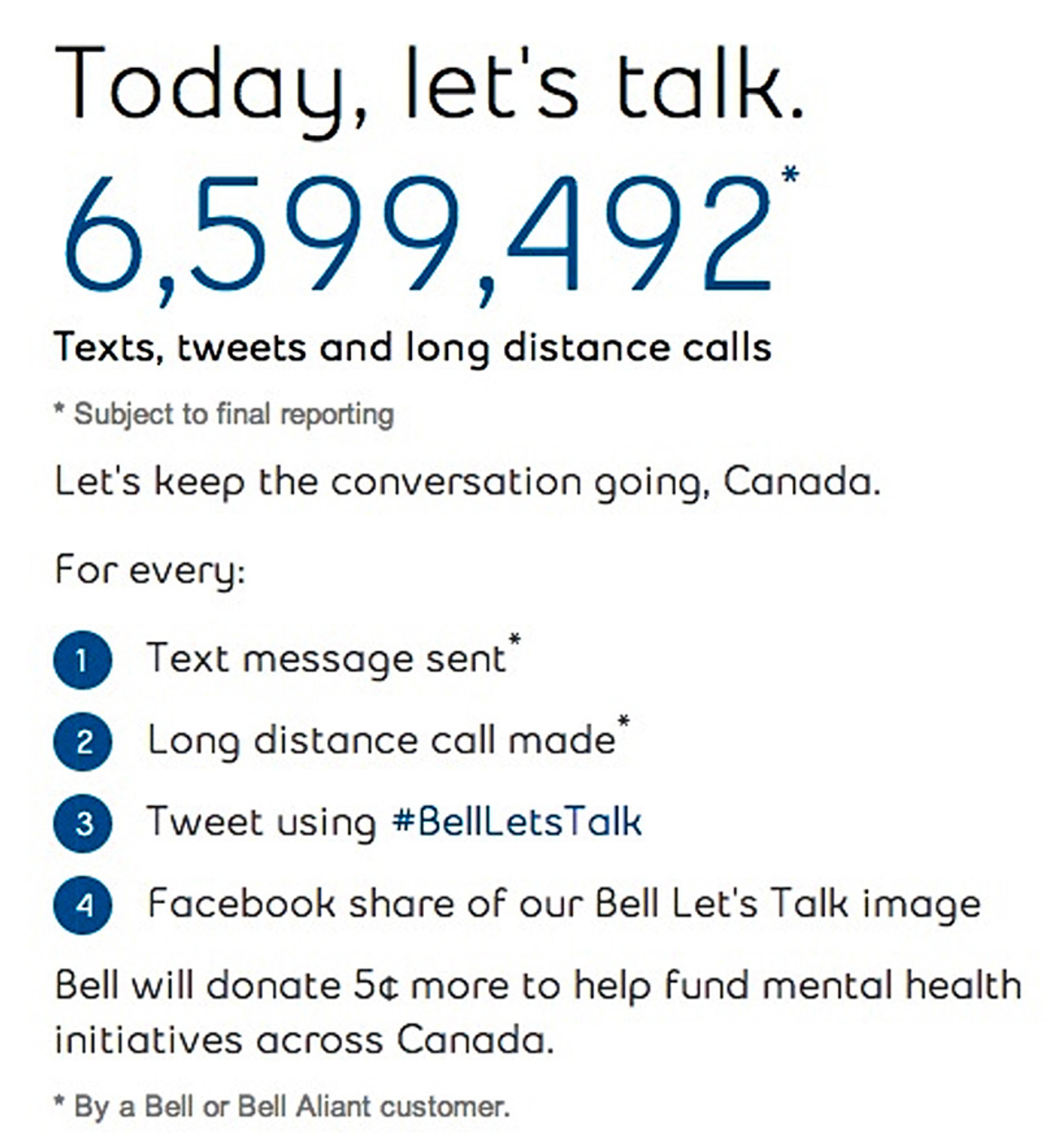

Across the Atlantic, a telecommunications company’s anti-stigma campaign #BellLetsTalk calls attention to the asymmetry between medium and message. Since 2011, the telecoms giant Bell Canada has encouraged users to post social media messages using the same hashtag – perhaps a positive message about how normal it is to feel anxious, or a more confessional one about someone’s actual personal struggles. One day a year, in January, the campaign pledges a donation to Canadian mental health organisations for each hashtagged post made or video seen online, plus any text messages sent over the Bell network. The company uses the total number of these ‘interactions’ as a key metric of the campaign’s success – interactions that could theoretically consist only of poison-pen texts and shitposts, so long as they bore the right hashtag and were sent with the right carrier. Multiple Canadian news outlets have picked up on this, arguing that Bell’s true goals seem to be to drive traffic on its network and launder its public image.

#BellLetsTalk ad

In all of these campaigns, the potentially deadly seriousness of the subject matter seems to be at odds with the casual manner in which people are encouraged to discuss mental health with friends or colleagues. This remains a problem worth our consideration. Let’s take seriously the idea that these organisations really are in the business of saving lives, of facilitating the kinds of conversations that might actually lead someone to conclude that life is worth the trouble of living after all. We must acknowledge the fact that we often encounter these serious entreaties in settings that remind us of the deeply unserious nature of our world. Adults unburdening themselves to Elmo, Depression Whoppers, soccer teams with official positions on healthcare debates… I often come back to this photo I took in Sydney during the pandemic:

A billboard in Sydney transitions from an R U OK? public service announcement to an advertisement for a deluxe skin cream. Photo supplied by the author

Am I a miniature deputised therapist, endowed with the healing spark of human kindness, or some shmo to sell deluxe sunscreen to? Real care for the currently, partially and potentially ‘mentally ill’– which, today, means a lot of people – is unlikely to come from these methods. It will not come from more efficiently shunting people into overburdened healthcare systems and volunteer-run crisis services. It will not come from corporate advertising campaigns, not even good ones, because, by definition, these do not address the root of the problem.

It will come from massively expanding the productive capacity of the public healthcare sector, training up more practitioners, building and upgrading infrastructure, and investing in basic standards of living for the poor and working classes of some of the world’s wealthiest societies. It will mean transforming the way people move between social services, clinicians, friends, family and community. It will mean addressing climate change materially, not only obliquely referencing how bad it feels. It will mean addressing the alienation of screens, tech feudalism, delivery apps, union-busted workplaces and the chronic enshittification of everything.

Like confession, therapy is not simply another form of chatting, as good as any other. It is a special zone of play, built for purpose – one that incorporates many of the best aspects of platonic love, but which is additionally bound by professional duty, specialised training and uniform standards of conduct. When it comes to the dark night of the soul, all ears are not created equal. Reminders to be a better friend, gentler family member or softer person are often welcome and will never be unwarranted. But let us not confuse this with the hard work required to address the very real mental health crisis to which such campaigns rightly call our attention. Only then will we find out just how OK we can really be.