My psychoanalyst’s consulting room was brown and functional. There wasn’t much inside it and its walls were bare aside from Claude Monet’s The Poppy Field near Argenteuil (1873). It shows a woman in smart 19th-century clothes walking through the grass holding a parasol. Impressionism – once revolutionary – has been reproduced so much it has become neutral, inoffensive; the perfect container for the anxieties of waiting rooms and clinical offices. At that time, my mood coloured everything I saw: the scene felt grey and sombre, although, looking at it now, I notice the flashes of blue sky. It was located behind my head, in my analyst’s eyeline, so I would see it only as I approached the couch. But I spent many of my early sessions holding it in my mind’s eye. I thought often about why it had been chosen to hang there. I wasn’t ready to share my despair with this person whom I did not yet trust. So I returned to the picture obsessively as a clue as to who my analyst was and what I might expect to happen in this unfamiliar place.

The artworks in a consulting room shouldn’t matter. Psychoanalysis is the talking cure: its medium is language. Sigmund Freud’s iconic couch was given to him as a present by a patient in 1890; Freud later made it standard practice for patients to recline. He found it was easier for them (and for him) to look inwards, to speak what they found there freely, if they gazed at the ceiling rather than at someone’s face.

But the space in which the conversation happens is important. I don’t believe I am the only person who has found themselves talking while also wondering internally how a particular print, painting or picture got there. Objects prompt associations, memories, thoughts, feelings, fantasies, imaginings – everything, in short, that is the raw material of psychoanalytic work. By virtue of being placed in the vessel of meaning-making that is the consulting room, artworks of all kinds – whatever they are – gain new value.

To understand the significance of art in the psychoanalyst’s office, it’s necessary to consider first Freud’s own space. Freud was a devoted collector who assembled more than 2,000 antiquities, all of which were shipped – together with his couch – to 20 Maresfield Gardens in Hampstead, north London (now the Freud Museum) when the Freuds fled Vienna from the Nazis in 1938. Neolithic tools, ancient Egyptian vessels, Greek and Roman figurines, a bronze model of a porcupine were on his desk. The objects gave him immense satisfaction. They drove the development of his theories, feeding his interest in the ways that the past is preserved within the present, in particular how behaviour from childhood is repeated in adulthood. Freud diverted his patients’ attention from his ceiling to show them his favourite things, and he deliberately exploited his possessions’ power to evoke. In Tribute to Freud (1956), the American poet H D, analysed by Freud in 1933-4, recalled him putting an ivory statue of Vishnu into her hands. She felt compelled and repelled by its ‘extreme beauty’.

Figurines and artefacts on Freud’s desk. Courtesy the Freud Museum, London

How a patient responds to the psychoanalyst’s art depends on their personal history; it will always be particular. But psychoanalysts must engage with a problem universal to their profession: how to set up their room, ready for patients to come and to project and to fantasise. The British Psychoanalytic Society, divided into Freudians, Kleinians and Independents, does not offer any guidance on the matter. Clinicians are free to set up their rooms as they like, just as they come to their own accommodation with Freud’s ideas, each finding their own space within the profession. In the autumn of 2024, I spoke to a psychoanalyst from each branch of the Society about the artworks and objects in their offices. Here are three case studies of how the psychoanalyst’s theoretical approach and personality – their tastes, preferences, histories – leave physical traces on the consulting room.

Dr T’s dog lays her head on my knee and looks up at my face, confident of my adoration. He calls her to him. She trots off at once to sit by his feet, settling down on the carpet momentarily before he decides to send her out for tracking in mud on her paws.

I’ve begun my investigation with a Freudian, hoping to follow the lineage of psychoanalysis directly. It’s an early evening in November, cold and dark on the other side of the bay window. We’re in Dr T’s well-lit consulting room in a brick house in Battersea, south London, with a bell marked ‘Office’ by its front door. There is a piano, its lid closed. Dr T gets up to show me the glacier-blue glassware that lines the mantelpiece above a marble fireplace. His own analyst collected glass too, he tells me, his hand on a vase that is squat and reassuringly weighty in form. There is a small statue of Freud on the mantlepiece beside the glass. It’s a copy of the statue of Freud that stands outside the Tavistock Clinic, made by the Croatian sculptor Oscar Nemon around 1970.

Sigmund Freud bronze statue (c1970) by Oscar Nemon, in the grounds of the Tavistock Clinic, London. Photo courtesy Wikimedia

We move right to the bookshelves. Dr T brings down what he calls ‘bits of history’ from them, one by one. A rock cracked into a neat geometric shape by the movement of sea ice. A silver salt cellar in the shape of a Viking ship. A miniature shoe made out of brass (‘Needs polishing.’)

Dr T tells me he didn’t set out to create ‘my little Freud space’, although, as I point out, the collection of little antiques on the shelves reminds me of Maresfield Gardens. At first, he felt nervous about putting his personal possessions on show. ‘Years ago, I was much more cautious, but now I’m not so bothered. Look at that mantelpiece – it’s cluttered.’

There are pictures on every wall. ‘They just happen to be prints I like. Clearly, it must represent something about me, because I’ve chosen them – I’m looking around now to remind me – yes, I did choose them all,’ he says. ‘They speak to me in some way. Even if I didn’t know at the moment that I acquired them, I didn’t know what they were speaking, something evolves in my personal relationship with them over the years.’

A nimbus floats above their head. Is the figure a builder, an angel, both, neither?

At the top of the couch is an abstract black-and-white print that, it takes me a moment to work out, shows a waterfall. Its position directly above the patient’s head suggests the cascade of drives and desires that Freud believed made up the mind – perhaps also the flow of speech in free association, the cornerstone of Freud’s technique, where patients are encouraged to share words, thoughts and memories spontaneously, without censorship or criticism.

When prone on the couch, patients can’t see the waterfall. They look instead at a 1985 print by the Scottish artist Bruce McLean, one of a series of 90. Dr T chose it at the Tate Gallery (now Tate Britain) as a leaving present from a clinic he worked at where he had been very happy. That year, 1985, the Tate had put on McLean’s performance Good Manners and Physical Violence, which parodied good manners by repeating ostensibly polite gestures until they became aggressive. At the time, Dr T didn’t know who McLean was. But he knew the print ‘felt different’ to the others.

Good Manners and Physical Violence (1985) by Bruce McLean. Courtesy Department for art

The image’s background is a bright teal, rendered in thick brushstrokes. A figure scratched out in white lines stands in front of a black rectangle, which evokes a door. A ladder leans to the left of the door. The figure carries a long roll of something under their arm. (In Good Manners, McLean used similar props to represent the everyday hard labour of decorum.) A nimbus floats above their head. Is the figure a builder, an angel, both, neither? The loose outline of a large face – closed eyes, nose, lips – are layered over the top of the top of the enigmatic scene.

When Dr T brought it back to the clinic to show his colleagues their present, ‘people gathered around speculating on its “meaning”.’ An elderly colleague in the group stated confidently: ‘I think it’s about death.’ Dr T didn’t ask him to extrapolate, but says the claim stayed with him. Its validity has become more apparent to him over the years, as he’s begun to imagine the image’s subject passing through the door and into another dimension.

‘I have one particular patient who says: “I really don’t like that” and there it is. He has to look at it every time he’s here,’ he tells me. ‘When a patient comments on the room, they’re commenting on the person of the analyst.’ It is, Dr T suggests, a way of asking the analyst: So, who are you exactly? ‘Or announcing their perception of them, without addressing the analyst directly, but by displacement.’

Such encounters are inevitable, Dr T thinks. He makes reference to the epistemological instinct, Freud’s term for the innate appetite for knowledge: ‘the instinct to know, to find out, which can be a positive thing – you know, of enquiry and wanting to learn – but it can also be intrusive and have a more destructive aspect to it.’ It’s one of the currents that feeds into the waterfall.

While Freud’s passion for objects was uncontained, one branch of his intellectual successors proposed that analysts should show much more restraint in how they furnish the consulting room – the Kleinians, who work with the ideas of the Austrian-British analyst Melanie Klein.

Bob Hinshelwood worked as a Kleinian analyst in London from 1972 to 2002. He’s since retired and now lives in Norfolk, so I meet him over a video call, which he takes sitting on a sofa upholstered in a woven beige fabric. The plain wall above his head takes up half of the frame. The screen’s reflected light catches occasionally against his glasses, forming white panes in front of his eyes as he gossips about goings-on in early 20th-century Vienna with a lively immediacy. We discuss the early analysts’ entanglements in the lives of their patients, and Hinshelwood brings up Freud’s one-time ally Sándor Ferenczi who, he says with a big laugh, ‘wasn’t sure whether to marry his patient or marry his patient’s mother!’ (He married the mother.)

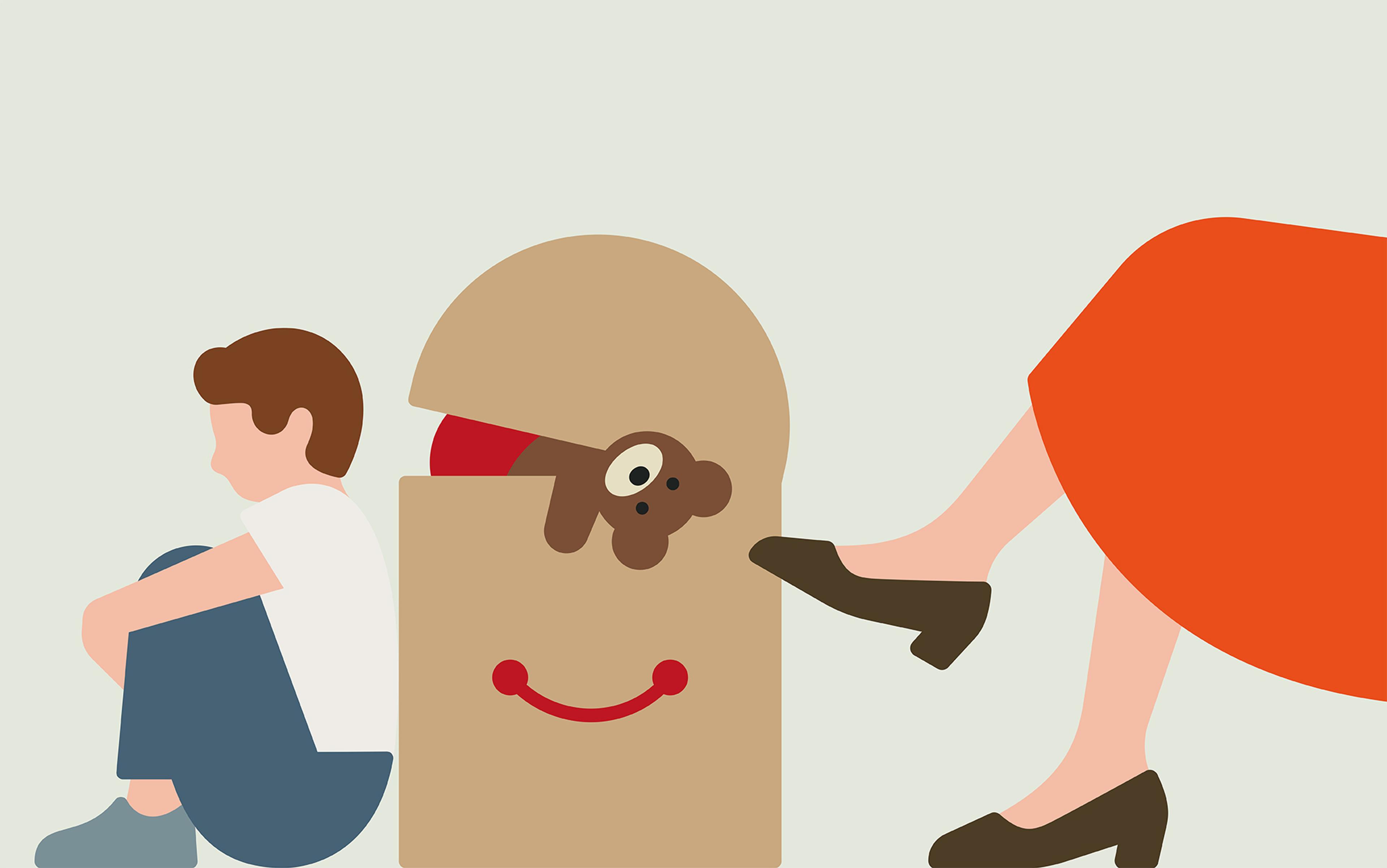

As he explains to me, Freud proposed that the ego developed during childhood as the child passed through the psychosexual stages – oral, anal, phallic. Klein revised this: drawing on her experiences treating children, she proposed that mental and emotional development begins from infancy, propelled by the conflicting feelings of envy and gratitude that the baby feels towards their mother.

Based on their earliest experiences, Klein said, infants form an internal relational system that they carry into adulthood, unconsciously applying it to the world. Klein’s writing, which attempts to reconstruct the baby’s inner world, is engaging but difficult. Hinshelwood’s book A Dictionary of Kleinian Thought (1989) communicated the concepts from her work clearly; his Clinical Klein (1994) mapped out how they could be applied in the consulting room.

Some Kleinians believe that to access the unconscious the consulting office space needs to be clear, uncluttered. During a series of clinical supervisions conducted in Brazil (and later published), Klein’s analysand Donald Meltzer, a prominent analyst in his own right, told the group that they should have nothing personal in their rooms, only a comfortable couch and chair. Meltzer later changed his mind, reflecting that he had made the recommendation following a bereavement, and that the advice was a product of his desolate state of mind. But, by then, the idea had taken hold.

The names on the spines could be read clearly from a distance. Patients said titles aloud occasionally

Hinshelwood’s consulting room was in Notting Hill, west London. It was in a side annex of his family house, accessed through a basement entrance. The close proximity between his work and living spaces meant, he says, that patients always had a ‘sense of something up there’ – Hinshelwood’s life, his family – as opposed to what was happening ‘down there’ in the room. Hinshelwood didn’t mind this. ‘To try to conceal oneself behind an ambiance of work and depersonalisation I would say is inappropriate. You always are a person, however your patient treats you.’

His room was filled with books. On the couch, patients’ eyes rested on a bookcase mounted to the wall. It was filled with ‘learned biographies’ of philosophers like Ludwig Wittgenstein and Bertrand Russell. The names on the spines could be read clearly from a distance. Patients said titles aloud occasionally, but Hinshelwood didn’t make much of this, he tells me.

He only had one artwork: ‘a little print … quite a nice little picture.’ But it was ‘really quite unobtrusive’, he stresses. It hung on the staircase that led up to his office where he wrote his notes on patients afterwards. Only he could see it from his chair by the couch; the patient couldn’t. And Hinshelwood doesn’t remember anyone walking up to it to have a proper look.

The print was produced in London in 1833, number 65 in a series of sketches of peoples’ heads. It shows a dark-haired woman in a teal dress with enormous puffed sleeves – the crisp fabric looks like it might rustle satisfyingly when she moves about – and a scooped back that shows the back of her smooth white neck. Her head is turned back towards the viewer, her eyes coquettish. Perhaps she’s at the opera: she stands behind an ornate balcony, the velvety curtains behind her parting suggestively in fleshy-looking folds. (Hinshelwood emails me later: ‘It’s a bit seductive and suggestive – and perhaps libidinal?’)

At the print’s focal point, the woman holds each hand in an O shape, her fingertips pressed together to represent glasses or binoculars. Underneath, in capitals: ‘DO YOU UNDERSTAND?’ Hinshelwood taps out the sentence’s syllables in the air with his hand as he relays the caption to me.

So it was for you, not your patients, I say. ‘It was for me. Yes! It was to remember I was supposed to be an understanding psychoanalyst. Understanding. That’s the focus of my life, I suppose. Patients always come to analysis divided between whether they really want an understanding of what it is they don’t want to understand – what remains unconscious – on the one hand, or whether they want help in supporting their defences against something they feel they can’t bear.’

So, the print confronted Hinshelwood with the question that drove his work. But it was a question to which he knew he could never answer Yes.

There is a danger with taking an ‘intellectual approach’ to peoples’ ‘heartfelt anxieties and conflicts’, Hinshelwood says. Being confident you’ve comprehended the patient can prevent you from connecting with them. Hinshelwood tells me about the British analyst Wilfred Bion – Klein’s student – who in 1967 wrote influentially that analysts should listen to their patients without memory or desire: each session must have ‘no history and no future’. By this, he meant that, once the analyst begins to theorise, their own unconscious assumptions and expectations take hold; they lose sight of the patient’s reality.

This means understanding is a state that must be strived towards, but never arrived at. Curiosity. Never certainty. ‘Understanding is a never-done process when we are focusing on the unconscious mind … We are never done with understanding.’

Before I meet Jonathan Sklar, he tells me he’s happy to talk but will be ‘silently discreet’ when necessary. My chair cracks loudly as I shift about on it in his consulting room in West Hampstead, northwest London. The creaking chair is the same that patients occupy when they come for a consultation, the first meeting, where the fit between patient and analyst is tried out. There is a blue rug, a couch with a neat row of white cushions, two chairs, a desk, many books. Statues and small objects from China, Peru, Egypt and Africa, most of them old, are on the shelves.

By this point, the rooms are acquiring a sense of seriality. I can see how Freud’s visual – as well as his verbal and textual – legacy are repeated. ‘It’s very Freudian but it’s my Freudian … It’s what’s accrued after 42 years of being a psychoanalyst.’ How long has he been in this particular room? ‘Some while.’

Sklar began his career as an analyst in 1983. He’s done much to develop psychoanalytic training in eastern Europe and has written widely, including about trauma and history in Landscapes of the Dark (2011) and about creativity in The Soft Power of Culture: Art, Transitional Space, Death and Play (2024).

He is from the Independent school, whose most prominent theorists include Donald Winnicott, who developed his ideas by working with families experiencing dislocation after the Second World War. Independents tend to have an open-minded, experience-based relationship with theory, taking from both Freud and Klein as appropriate to the situation. They give weight to the mother’s consistent holding and handling, which, they believe, is what enables the baby to develop a coherent sense of self: Winnicott’s ‘good enough’ mother succeeds if she is reasonably attentive to the child, no more. I wonder if a consulting room can play the same role as the ‘good enough’ mother, providing a stable, but not rigid, environment for exploration.

‘I thought, that’s a very good picture that can restfully be – to be noticed, or not be noticed’

I tell Sklar I am curious about what meaning art has in the consulting room and he begins by explaining the layout of his office. ‘It’s very important to locate where the door is. So sitting there, I’m not in your way to get out the door … I have set it up with a freedom for the patient, because I’m not here to impede … The patient says “I can’t go past you.” Well, they can.’

He points out a square painting that has been with him since the beginning of his work. A textured cream wall bisects the canvas. On one side of the wall is a tiled floor on which two small potted plants sit. On the other side is a dense mat of vegetation. At least four different kinds of trees and plants curl and reach, their vitality communicated in sweeping, energetic strokes. In the distance is the upper storey of a Mediterranean-looking building, blue shutters at its windows.

‘When I saw that picture a very long time ago, I liked it for me. And I thought, well, that’s a very good picture that can restfully be – to be noticed, or not be noticed. And very often it is noticed.

‘Everybody who comes into this consulting room has a wall of some sort. A small one. A big one. A wall followed by another wall followed by another wall but at some point – for me – it’s a measure of, you have to actually get into the other place which is verdant. To have a more creative life you need to transcend that wall somehow. Which, in a way, is the dilemma of the patient. Whatever their problem, they can’t get to where they want to go or want to be.’

And when is the picture mentioned by patients? Sklar won’t tell me that. But, he says, it is ‘absolutely extraordinary’ when the patient notices something of relevance in the room. ‘The object to be found is found. When it happens, the patient has a real sense of Gosh. I found that here. It’s a moment where there isn’t so much of a wall. You can get through.’

‘This man thought this humble little thing was worthy of an artistic eye. That’s very relevant to psychoanalysis’

On the other side of the window and above Sklar’s head is a copperplate etching of a plant from Michael Landy’s series ‘Nourishment’ (2002). It was Landy’s first project after his Break Down (2001), in which he catalogued everything he owned – it came to 7,227 items – and then destroyed them. ‘Nourishment’ is a collection of etchings of weeds he found growing in London’s car parks, pavements and brownfield sites.

Creeping Buttercup (2002) by Michael Landy, etching on paper, from Nourishment series © Michael Landy. Published by Paragon Press. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Paragon | Contemporary Editions Ltd, London. Photo: Richard Thomas & Prudence Cumming

‘I was interested in the paucity of the object,’ Sklar says. ‘It’s something so humble. It’s not even to be looked at as you walk down the streets. And this man thought that this humble little innocuous thing was worthy of an artistic eye. And I think that’s very relevant to psychoanalysis, to some patients who come for analysis. That they think there is nothing much to them. And it’s probably not true. Or it’s hidden. Concealed.’

‘It’s also the idea that someone coming into this room might think they have to find some big thing that they don’t know about. Some big idea or some deeply hidden thing. But it might be something minuscule, out of the sightline even.’

It’s complicated to have real flowers in the room though, Sklar says (although he likes tulips). ‘Because flowers are always a memento mori. As soon as they’re cut, their dying is enhanced.’ But, he adds, ‘there’s nothing wrong in that, because part of analysis is to have some recognition that one has to give up life at some point also.’

I cross the room to lie on the couch. Stretching out, I notice the wall right in front of me is blank. ‘I’m all for that blankness as well,’ Sklar says. ‘Everywhere is not filled. I have plenty of other pictures that I could put there, but I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to have an empty space for thinking. The empty frame that can be filled somehow.’

From the couch I can now see the row of antiques on a shelf on the opposite side of the room, behind the consultation chair. Like Dr T, Sklar has the Tavistock Freud statue. His is one of 15 maquettes (scale models) made as preparation by Nemon, which have since been circulated among analysts: ‘In time, I was given one.’

Sklar’s maquette manifests how the consulting room’s artworks are a medium through which the psychoanalyst works out their relationship with their profession’s past, how they handle the things that came before. Of course, Freud is there. But Sklar takes pleasure in showing me that he has positioned him according to his own liking. The model Freud is placed deliberately on an angle, so his head is turned away from Jonathan’s chair. ‘His presence is there, but he’s not eyeballing me. He’s being discreet.’

It strikes me, by contrast, that eyeballing is exactly what I’ve done. I have pried into spaces that are normally private, and subjected analysts to my gaze. But a consulting room is not complete without its patient. They give its contents their meaning by layering their personal history into the space, using it to form their own internal picture of the office in which they talk. A psychoanalyst might suggest that what I’ve provided here are really three case studies of myself – a record of whether the sky looked blue or grey that day.