The art of ‘being for another’ – following, listening to and making sense of another person’s world – has been practised for millennia. Humans have always discussed their lives, their values and their problems, trying to find meaning, solace and joy. Experts at this sort of discussion have been called wise women, shamans, priests – and now therapists. Then, starting with Sigmund Freud, came a series of attempts to create a science of psychotherapy out of it.

But there is very little science to it.

Being there for another person is uncomfortable. It is difficult. There is no peace, since the other continually changes, but that is the art. Doing it well takes experience, intelligence, wisdom and knowledge. Apart from a weekend’s worth of basic ground rules, it cannot be taught. From observing the people who do it well, I have concluded that it is an attitude perfected by seeing thousands of clients, reading hundreds of books on philosophy, art, science – and some trashy romance novels. It is enhanced when the practitioner has voted for a range of political parties, had a number of careers, and adhered to a religion or three – how could you possibly understand the anticipation, the fervour or the profound loss of purpose in seeking, finding and losing God unless you had undergone something like that yourself?

I became a psychotherapist and psychologist to maximise the good I could do in the world. It seemed obvious that helping people by engaging with the root of their suffering would be the most helpful thing to do. I also became a child psychotherapist to address the roots of suffering in childhood, where they seemed to stem. I experienced how deepening into a feeling could transform it, and learned about pre-natal trauma; I even wrote a doctorate on trauma. Now, two decades into my career, I practise, lecture, supervise and write about all of these things, but increasingly I reject everything that I learned. Instead, I practise the art of ‘being for another’, an idea that arose in conversation with my colleague Sophie de Vieuxpont. I’m a mentor, a friend in an asymmetrical friendship, and a sounding board and critical ally assisting people as they go through the complexities, absurdities, devastations and joys of life.

Along the way, over years of practice, I lost faith that awareness was always curative, that resolving childhood trauma would liberate us all, that truly feeling the feelings would allow them to dissipate, in a complex feedback loop of theory and practice.

The effect of your family environment matters very little when it comes to your personality

It started with returning to an old interest in evolutionary biology, with the release of Robert Plomin’s book Blueprint (2018). An account of twin studies, the book draws upon decades of twin statistics, from several countries, and the numbers were clear: childhood events and parenting rarely matter that much in terms of how we turn out.

That caused me to re-read Judith Rich Harris’s book No Two Alike (2006), which also examined twin studies along with wide-ranging studies of other species. Harris proposed that the brain was a toolbox honed by evolution to deliver sets of skills, leaving each of us utterly unique.

These books are perhaps summed up best in the second law of behavioural genetics: the influence of genes on human behaviour is greater than the family environment. I noticed my defences popping up, desperately trying to find holes in the science. But at the end of the day, without cherry-picking data conforming to what I learned in my training, the simple fact was this: twin sisters with identical genes raised in totally different families developed very similar personalities, while adopted sisters with no genetic links raised in the same family had very different personalities.

That finding, from the journal Developmental Psychology, undermined years of learning in psychodynamic theory. It means that the effect of your family environment – whether you are raised by caring or distant parents, whether in a low-income or high-income family – matters very little when it comes to your personality. If you’ve ever had any training in therapy, this goes against everything you have been taught.

Yet the tenets of psychotherapy did not reflect my clients’ lived experience, or even my own. Instead, we see what we expect to see, and we make sense of our past based on how we feel now. If I am sad, I will recall deprivation and strife in my childhood, while my happier brother remembers a more positive situation; consider the memoirs Running with Scissors (2002), Be Different (2011) and The Long Journey Home (2011), each a radically different depiction of the same family.

In the few longitudinal studies that have been made, where we track children and their adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) from early years to adulthood, there is no link between ACEs and subsequent adult mental ill health. There is only a link between adult mental ill health and the ‘recollection’ of ACEs. This may seem wildly counterintuitive to a profession steeped in trauma theory. ACEs have not been shown to cause mental ill health; it is rather that, when we suffer as adults, we interpret our childhoods as having been bad. I’m convinced that there are rare exceptions to this, of truly horrendous childhood experiences that do leave a mark, but even that certainty falters when I consider the fact that events that supposedly traumatise one person in a group fail to traumatise the others.

If you are denying what I’ve just written out of hand, you may be doing what religious fundamentalists have been doing for millennia. What I say may feel heartless, cold or politically toxic, but feelings aren’t epistemically valid grounds for rejecting information.

Our treatments could be largely pointless and potentially harmful

Instead, consider this: it is possible to care about suffering while reassessing your analysis of how it is caused and how it can be addressed. Perhaps a vast majority of therapy trainings are wrong about why people suffer. People in other cultures with radically different worldviews about how suffering develops and how best to deal with it also care deeply about helping people – they simply have a different way of doing it.

We need to reconsider why people suffer to help them in a better way. Freud and more recent trauma proponents like Gabor Maté tell us that our personalities and sufferings stem from how we were treated as children. This may resonate with us, but it could actually be wrong. If it is wrong, our treatments could be largely pointless and potentially harmful, and we need to critically examine these theories more carefully before we, as a profession, do more harm.

Historically, in many cultures around the world, from Nigeria to Malaysia, or the West more than 50 years ago, childhood has been seen as just one of the stages we move through, with no sacred status. We learn all the time, but suffering stems from how we now, at this time, relate to the world and what our current circumstances are.

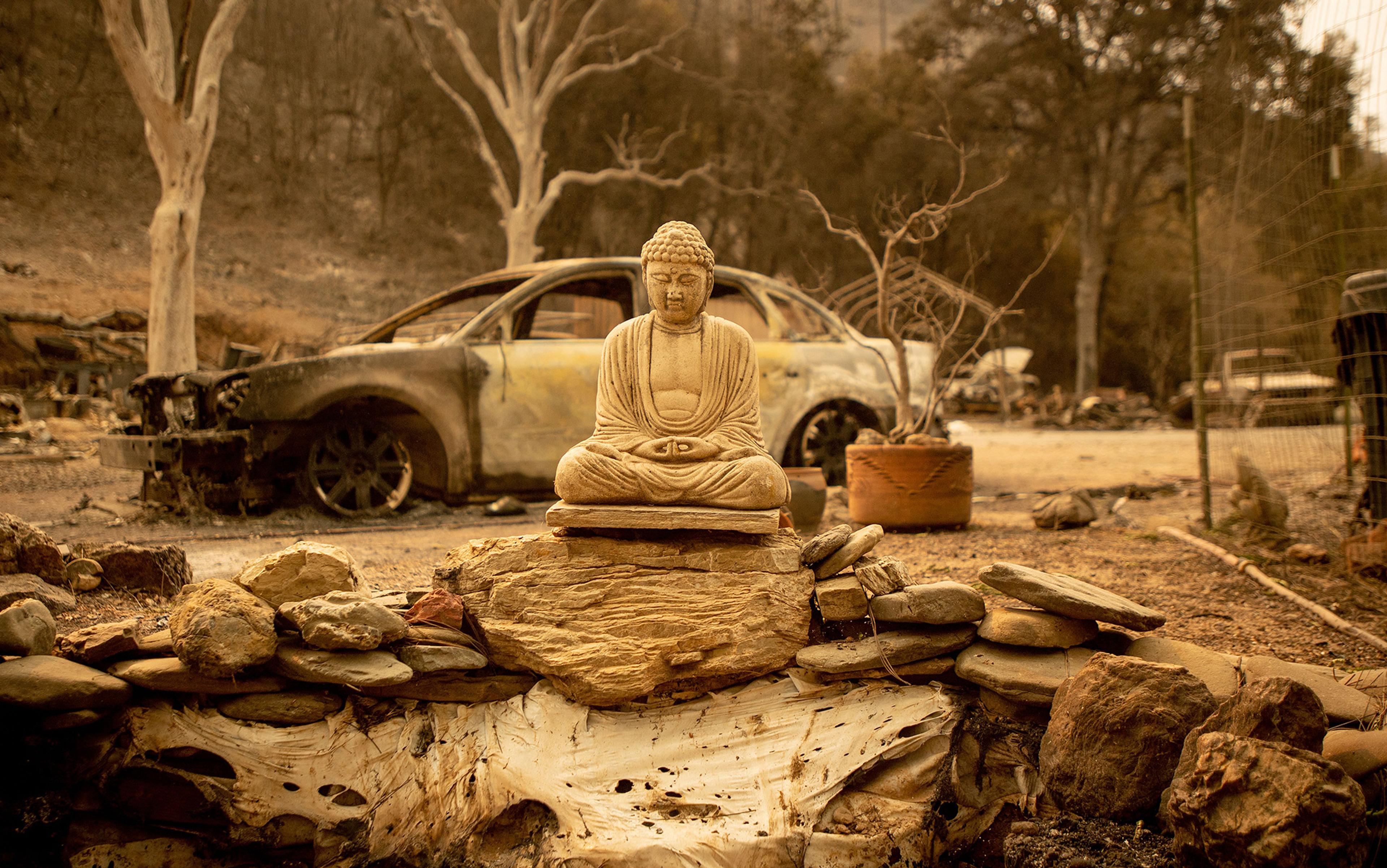

Isn’t it a bit arrogant that so many in the West assume that this new, unevidenced theory – that suffering stems from childhood – should be universally true, or even true for us? How does the psychodynamic therapist, faced with their suffering client, feel resolute that they should dredge up the past, when philosophical traditions from across the world say the answer lies in the here and now? The Buddha, Lao Tzu, Aristotle and Jesus didn’t mention a word about childhood’s irreversible stain on the human condition – they saw us as individuals living through choices in the now. A millennium later, Al-Ghazali and Thomas Aquinas still worked on the here and now. Even two centuries ago, G W F Hegel, Søren Kierkegaard and William James didn’t obsess about childhood.

If we were all doing brilliantly now, and if all the therapies that we pay so much money for worked as well as they claim to, maybe we could feel more confident in dismissing all of that. But they’re not, and surveys of happiness indicate that many Western women – therapists’ main customer demographic – aren’t doing brilliantly either.

At first, I couldn’t accept all this. Then Abigail Shrier’s bestseller, Bad Therapy (2024), described how therapeutic culture exerts a toxic and often harmful effect on culture at large. I was working with children, but was psychodynamic therapy, where we discuss the past, actually good for them? Shrier does not discount the occasional usefulness of children talking to adults, but also highlights the risks involved in turning it into routine treatment.

Children, even more than adults, become what they focus upon. If the focus is difficult feelings, these difficult feelings usually amplify rather than decrease. Yet this is what child psychotherapy focuses on – getting the kids to notice their difficult feelings and talk about them in the vain hope that all these difficult feelings magically disappear. My experience echoes the research Shrier cites: children are far more likely to identify with the feelings and fall down a rabbit hole of ever-increasing distress. Get a child to play out their anxiety in the sandbox, as I was taught to do, or to describe where they feel it in their body or what the scary monsters in their nightmares look like, and you might feel you’re helping them explore their emotions, but they end up stewing in them instead, invariably far more anxious than when they arrived.

There is a place for specific techniques in dealing with social anxiety, phobias and panic attacks. Such straightforward techniques, today classified under the umbrella of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), draw upon Buddhist, Stoic and traditional wisdom in order to hack our minds when we careen off into unhelpful rabbit holes. But why ask children to deepen into difficult feelings? This disrupts children’s natural process of resilience and of finding the good.

The issue is not merely with the therapeutic approaches offered in schools. We need to see it as a larger cultural idea that seeps out through parenting. Feelings are seen as central, when in fact they are vague and transient approximations of a situation. The whole point of parenting a child is to scaffold and develop their executive functions so that they develop adult emotional and intellectual capabilities. This means teaching them that how they feel is not necessarily how things are, and that they may be held hostage by emotions if they don’t learn to move on from them. A child’s anger should not automatically be honoured, and their resulting difficult behaviour should most certainly not be rewarded with special accommodations.

Jim was encouraged to lean in to his anger rather than being expected and incentivised to move on

As an example, a case study: Jim’s family contacted me in a state of anxiety about their increasing inability to cope with Jim’s behaviour. They were highly caring parents who began to notice Jim struggling to self-regulate his impulses and lashing out at other kids. So, they sought professional advice from an experienced and fully accredited therapist. She recommended they sit with Jim and allow him to express his feelings safely, which often meant Jim lashing out at them.

When this didn’t help, and Jim began to get into trouble in school, their therapist recommended they take a trauma-informed approach. They had all lost a much-loved family member when Jim was small, now theorised as accounting for Jim’s disrupted emotional development. Jim’s anger was understandable in the context of what had happened, and he needed to be free to express it. Trauma-informed behaviour management entailed making sure Jim felt safe when he was dysregulated (which is a polite way of saying when he was screaming, hitting and kicking people) and then asking him what he needed, showing him affection and finding activities he enjoyed such as gaming to reconnect.

After that, they could ask Jim about his feelings. Jim’s school adopted a similar strategy, with a student support worker ever-present to play with him when he disrupted the class. The idea was that forging strong attachment relationships with caregivers in school would help Jim feel emotionally safe, and his behaviour would then improve.

‘It didn’t,’ his tearful mum explained to me. He recently got excluded and now refused to go to school.

These weren’t random crackpot theories. The psychological literature on attachment and trauma is extensive and mainstream. Many schools and mental health professionals have mandatory training in these approaches. But they also didn’t work. Jim was encouraged to identify with his anger, and to lean in to it rather than being expected and incentivised to move on. He was inadvertently taught that getting angry or violent in class would get him a free pass to play football instead of doing mathematics. The outcome was that, despite having thoughtful and motivated parents, Jim drifted further and further to the edges of the social world, because the therapeutic obsession with validating his emotion stopped him from learning the social rules that allow us to take part in it.

Because a central premise of child psychotherapy – helping children explore difficult emotions – is looking increasingly like it risks iatrogenic harm (ie, the treatment itself being harmful), I have started to decline work with children and am instead offering to work with parents or the broader system around the child.

Western morals draw upon ancient Greek and Christian ideas of virtue, humility and critical thinking. They form the core of psychotherapeutic thinking but have become increasingly imbalanced. The virtue and humility that was required to be for another has increasingly been distorted into victimhood for the client and heroic saviour identities for the therapist, while critical thinking has effectively become a silencing of any critique of current therapeutic or ideological dogma.

We like to see ourselves as critical thinkers, but the critical thought never seems to mention that some 10 per cent of clients get worse after starting therapy – in these cases, therapy might be not merely unhelpful but actively harmful. If you’re told that you must listen to your momentary and subjective feelings of annoyance and hurt, and view them as your truth, minor interpersonal discomforts are much harder to let go of gracefully. If you’re then told that your troubles with relationships stem from your parents’ failure to be fully present and meet your needs in childhood, the risk is that you will become more critical of your relationship with them at a time when perhaps you need that solid family bond the most. More than a quarter of Americans have cut off a family member; it is statistically improbable that most of these estrangements are for the sort of egregious abuse we might imagine merits it.

This is not talked about, taught or researched in our training institutions. Imagine if the benefits of capitalism or social media were extolled, and no one ever considered the shadow side? In a profession that gives a lot of airtime to Freud and Carl Jung, the Shadow should be central to our endeavours, yet we fail to consider this giant Shadow of our profession – that we regularly do harm.

Sri Lankans don’t see their civil war or their tsunami as traumatic

This lack of self-critique coupled with a sense of infallible virtue creates a zeal for disseminating unevidenced and potentially harmful memes from psychotherapeutic culture into mainstream culture. We see this when distress is increasingly explained as a reaction to ‘trauma’ or parents who in some way did us wrong. We see it in schools where children who would benefit more from clarity and boundaries instead get ‘trauma-informed’ carve-outs that stop them from being supported to develop the behavioural and life skills they will need to get on in the adult world.

Spurious trauma theories convince entire sections of society that they are deeply broken and require our services. How dare we believe that every other culture somehow misunderstood how suffering works, indeed our own culture until Freud? Sri Lankans don’t see their civil war or their tsunami as traumatic – in fact, when an army of trauma counsellors descended upon the nation after the tsunami of 2004, the University of Colombo pleaded with them to cease seeing suffering as traumatisation as it was undermining people’s resilience. Sri Lanka happens to top the charts for wellbeing in the ‘The Mental State of the World in 2023’ report despite such denial of the gospel of trauma.

No other culture that I know of believes that bad events create indelible stains on our minds, stains that forever taint our experience of the world. Bad things have happened throughout time, and they were (and are) bad enough without adding to them by insisting that some ‘trauma is held in the body’ in inescapable ways. Telling people that they have been harmed forever by others in their lives creates resentment and harms relationships. If you peddle these kinds of stories, or simply believe them, consider reading up on the shaky science on which they are founded. And while therapy talks the talk about cultural competence and learning from other ways of thinking, it rarely walks the walk. We can learn from non-Western cultures’ takes on suffering, where we stay in the now, suffer in the now, and heal in the now.

Could it be dangerous to normalise therapy as the go-to way of dealing with difficulty? Therapy is a parasocial relationship, a form of unbalanced friendship. The relational component of being a therapist is like being a sex worker – there is a relationship, but it exists fully for the client. The payment and boundary rules bend the relationship towards the client – it is about them, because the reciprocity has been paid for. In a perfect world and life, there wouldn’t be any need for sex workers and therapists, because we would all have good sexual and non-sexual relationships, but in the real world such goodness is not always on offer. So, therapists and sex workers step in to fill the gap, offering experience of relating, in their respective domains, and hopefully allowing the client to learn enough about themselves and others to go into the real world and find real, better relationships.

The danger arises when the therapeutic relationship becomes a replacement for real-world relationships – when we are encouraged to ‘take it to therapy’ rather than attempting to engage with family or friends about painful and sensitive matters. Real-world relationships are strengthened by difficult conversations, and communities evolve by discussing matters that lurk at the edge of the respectable.

The therapeutic space shouldn’t insulate real external relationships from the dark messy internal relationships of ourselves – it should serve to occasionally incubate, prepare and clarify difficulties only with the express intention of sending the client back out to real relating. To return to the sex worker analogy, my job should not be to replace the unwilling spouse, but rather to be the open-minded sex worker who offers different ways of being that can transform the real marriage out there.

All the above left me with the problem of putting this new mindset into practice. Was it possible to reconcile the problems of therapy with continuing to practise as a therapist? It’s a work in progress and these are my imperfect solutions. My website no longer promises cures. It doesn’t flaunt my extensive training in psychodynamic nonsense. It just offers discussions about your life – discussions that have seemed useful to clients in the past, and that might be useful to you now. No promises.

I try to draw upon sources outside the bubble of the past 50 years of Western thought: ideas that persist and transcend cultures tend to do so because they have value. Buddhism offers insights into mindfulness, especially if we remember all eight aspects of it, which include efforts, actions and speech. The pragmatism of William James, Friedrich Nietzsche’s ideas of will and choice, and Socrates’ questioning style are all available to my mind and the therapeutic relationship, but the client leads. It is a discussion about their life, what meanings they assign to it, how they live out those meanings. It is a celebration of the good stuff and a place to name the bad stuff, but most of all it is a space where we focus on the now and the future, on what they actually want to do and how obstacles can be overcome. I see my job as clarifying the ethics and aesthetics of my client – when we speak of ethics, I actually think that we are grounding it in aesthetics, so that what seems elegant and right to us is usually only subsequently clad in the more dispassionate garb of lofty ethics.

There are no hidden maternal attachments or strange counter-transferential stuff

I believe that the true therapeutic work is to battle resentment. Resentment is the core of all my ills, the pain itself isn’t. Resentment arises when we are in pain but believe that we are entitled to not feel pain. This is complicated to engage in, especially since it borders on rights and politics. If I feel that I have the right to publish this article in The New York Times or have the right not to be offended by critical reviews of it, then the pain of being rejected by The NYT and reading vicious takedowns of my sage wisdom will be infinitely multiplied. My entitlement will make my basic pain so much worse. I also believe that forgiveness and gratitude are the greatest allies that we have to battle entitlement and resentment. And they are easily developed.

Notice that I wrote that I believe the above to be true. I don’t know it. It works for me, resonates with me, and has been a theme for religious and nonreligious theorists from Siddhartha Gautama and Jesus of Nazareth to Nietzsche. But the simplicity of the theory allows my client to work out whether it applies to her or not – there are no hidden maternal attachments or strange counter-transferential stuff that only I, the expert, can decode. If my client insists that rights-based thinking can co-exist with gratitude, I may even learn from her (I did – thank you – if you read this, you know who you are).

Having let go of empty theories, and having informed the client that no magic resolutions will be forthcoming from my end – that their life is their responsibility – I find myself grounded in millennia of wisdom, in a lineage of people offering support in how to live. I can lean in to my clients, be curious about their stories, engage in their dilemmas, and flesh out their life-worlds as an intrepid explorer leaving no stone unturned. On one hand, I feel less burdened by responsibility since there is nothing I ‘should’ do; on the other hand, the responsibility is greater since I take on all of the client without obfuscating theoretical filters. I have let go of therapeutic theory, and I think I am a better therapist for it.