‘The greatest use of life is to spend it on something that will outlast it.’ – William James, The Thought and Character of William James (1935)

A year ago, on a late afternoon in November, I decided to walk the seven miles from my hotel in Manhattan to Brooklyn’s Community Bookstore. It was a cool day, on the cusp of evening, at a moment when things, even grimy New York-type of things, seem to glow, and I was so busy looking around that I almost didn’t notice the small white sign that someone had placed at the bottom of Brooklyn Bridge. The green lettering was newly painted and read: ‘LIFE IS WORTH LIVING.’

For many people, life’s worth is never in question. It never becomes a topic of conversation or debate. Life is simply lived until it is not. But something bothered me: if life’s worth is so obvious, why was the sign put up in the first place? It is because there are those of us who occasionally find themselves on the top of the bridge, contemplating a quick and fatal trip to the bottom. Decades after battling depression in 1870, the American philosopher William James wrote to the philosopher and poet Benjamin Paul Blood that ‘no man is educated who has never dallied with the thought of suicide’.

In the 1770s, David Hume, one of James’s intellectual heroes, had argued that self-murder should not be regarded as illegal or immoral since it hurt no one other than the perpetrator, and in many cases might alleviate great suffering. Romanticism, which arose in the subsequent generation of thinkers, only deepened the sense that life – and death – should be determined freely, by passionate individuals. If you wanted to exit life abruptly, by one final choice, that was largely up to you. One of James’s favourite books as a young man, one which probably only deepened his sense of existential insecurity, was the Sorrows of Young Werther (1774), Goethe’s story of a character who kills himself on the sharp end of a love triangle. Perhaps life cuts so deeply that it is understandable, even respectable, to escape. More likely, the Romantics – and James – occasionally regarded suicide as a way of taking hold of life, controlling its machinations by bringing them to an end. We are all slipping toward the grave, uncontrollably. Maybe it is better to choose to fall off.

To my surprise and delight, the walkways on the bridge were empty. I’d have the view to myself. With a maximum height of 276 feet (84 metres), it was once regarded as one of the seven wonders of the industrial world. During its construction, 27 workers died, before it was completed in 1883; two years later, Robert Odlum became the first man to jump off the bridge. A swimming instructor who wanted to prove that descending through air at high speed was not necessarily fatal, he sadly died. In the next century, approximately 1,500 people have followed Odlum, for different reasons. I’m not sure how many people are saved by the sign, but I am inclined to think that it is highly ineffective.

It was chilly at the top. I looked across to the Statue of Liberty in the harbour and then back into Manhattan where James had grown up. Then I looked down. There was a terrifying liberty in this – the choice to live and die in a particular moment, as time stretches out endlessly in either direction. After reading James for most of my adult life, this liberty still has its appeal. I think it always will. In the first decade of the 20th century, James developed American pragmatism, a philosophy that held that truth should be judged by its practical consequences. It was a world-ready philosophy that, at its most basic, was supposed to make life more liveable. And it does, for the most part. But if pragmatism does save your life, it’s never once and for all. This is a philosophy that remains attuned to experiences, attitudes, things and events, even when they are the tragic ones. While James occasionally disparaged Arthur Schopenhauer’s pessimism (and refused to give a cent to a memorial in honour of the 19th-century German philosopher), James’s posthumous writings reveal a deep respect for the grim thinker’s willingness to stare clear-eyed into the gloom of human existence. There was something like courage in this brutal confrontation with quickly impending darkness.

According to James, the sign at the bottom of the bridge should be repainted or at least amended: LIFE IS WORTH LIVING – MAYBE. As he said to a crowd of young men from the Harvard YMCA in 1895: ‘Is life worth living? It all depends on the liver.’ It is up to each of us to, literally, make of life ‘what we will’. These days, when I peer down from great heights, in addition to experiencing vertigo, I almost always think about Steve Rose, a young black psychology graduate who threw himself off the William James Hall at Harvard University in 2014. Perhaps James’s way of thinking could have saved him – the suggestion that he was still in charge of his life, that the decision to end it all might be reasonable, even respectable, but so too was the possibility of continuing to live. The possibility was right there – still, always, even in the shit and rancour of it – for him to explore. Perhaps he thought that choosing to die was the only free decision at his disposal, but James always suggested there might be other options.

For the majority of people, free will can be exercised in any number of ways (which don’t have to include committing suicide), and in many of these cases one can choose to embody new habits of thought and action. If meaningful freedom seems evasive or unrealistic, most of us still have a choice about what to see and what to look past. This too can be worthwhile. ‘The art of being wise,’ James suggested, ‘is the art of knowing what to overlook.’ Maybe these possibilities could have kept Rose alive for even longer than they did. Maybe not. I don’t presume to be sure.

I think one surefire way to send jumpers off the edge is to pretend that you know something they don’t: that life has unconditional value, and that they are missing something that is so patently obvious. On the ledge, I suspect that they’d detect some deep insecurity or hubris in this assertion. And they might jump just to prove you wrong. Because you would, in fact, be wrong. In James’s final entreaty in his essay ‘On a Certain Blindness in Human Beings’ (1899), he reminded his readers that they often don’t have a clue about how other people experience the meaning of their lives. Better to leave it at ‘maybe’.

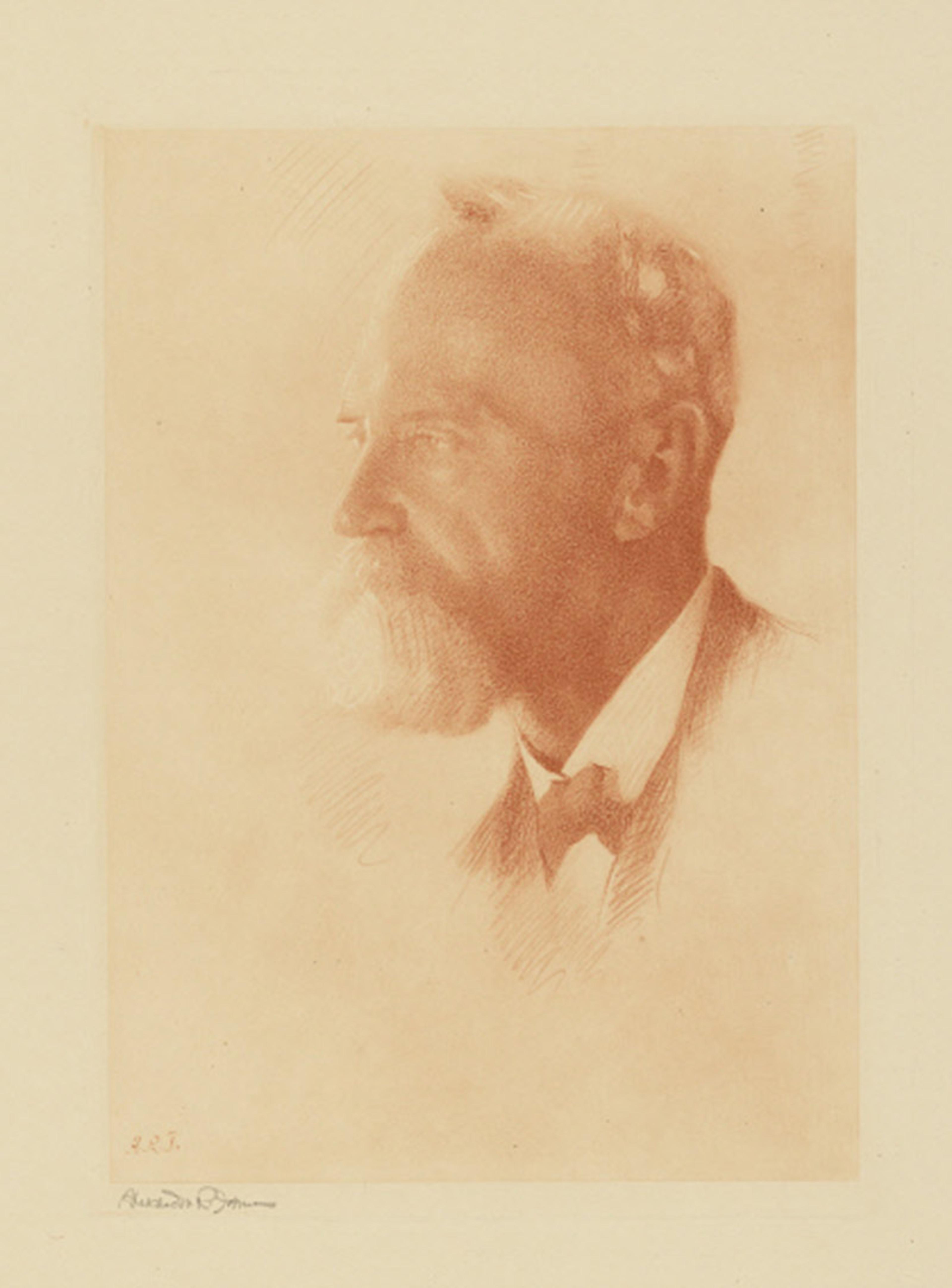

William James by his son, Alexander Robertson James. Collotype on paper. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

I looked across the water as the sun skimmed the cityscape. Night would fall and a million stars would once again compete with a million electric lights. In the short term, the electric lights will win. But in the indefinite long term, the stars will. Between these poles, it’s anybody’s guess. For now, I believe that James’s ‘maybe’ – the open question of life’s worth – is right, or at least right for me, because it maps my existential situation as one who is not always entirely sold on life’s value. It is also right, I think, because his ‘maybe’ is roughly fitted to the open question of the cosmos. Everything, from smallest eukaryotic being to the most complex organic system, is in the process of making its own guesses, the first proto-logical step in what we humans call ‘inferences’. Without good guesswork, there would be nothing like adaptation or growth and, for us, there would be nothing like meaning.

James followed his friend and fellow American philosopher C S Peirce in believing that the world is teeming with hypotheses, with the ‘maybes’ that make life, in all its many forms, possible, and make our lives worthwhile. For James, stars do not burn, much less appear, in perfect order, and human lives are not settled in advance. As Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote in his essay ‘Circles’ (1841), one of James’s favourites: ‘Let me remind the reader that I am only an experimenter.’ The ‘maybe’ remains constant, or as constant as a ‘maybe’ can. And this is for the best. It gives us something to watch and expect and experience. Persistent variation gives rise to persistent wonder and, for James, this sense of mystery – of chance – was often enough to see him through when other practical measures failed him. ‘No fact in human nature is more characteristic,’ the mature James asserted, ‘than its willingness to live on a chance. The existence of the chance makes the difference … between a life of which the keynote is resignation and a life of which the keynote is hope.’

If you throw something off a bridge into the water below, it breaks the surface and is immediately gone. Just G-O-N-E, a four-letter word of finality, like ‘dead’ or ‘fate’ or ‘lost’. There’s no chance of getting it back or preserving it, no matter how desperately you might try. Over the years, I’ve often imagined what it would be like to lose something precious in deep water, something far more precious than one’s keys or phone. For small material objects, I suspect that there is little hope of preserving anything. And I have entertained the possibility that this is the case with everything: keys, phones, wallets and lives. Maybe everything just departs without a trace. Some philosophers would be perfectly happy with this explanation – that everything is in the process of passing away, that at the end of the cosmic day, nothing will be left. I am just not one of these philosophers. Neither was James. The certainty of this fatalism runs counter to his ‘maybe’ and counter to a hope that is, for me, hard to live without.

Take an object – a small rock or a phone – to a shallow river. Throw it in. On a still evening, the ripples are still moving, still growing, when the object comes to rest on the bottom. The disruption at the point of entry is the first to vanish, but the consequences of the event radiate concentrically even as they dissipate. In a narrow river, with steep banks, the waves strike the shore, recoil to the centre, and make for the opposite side. The small perturbations are real, regardless of our ability to feel them. Something is left.

‘Our life is an apprenticeship to the truth that around every circle another can be drawn,’ wrote Emerson in ‘Circles’. Fifty years after the essay was published, James finished the Principles of Psychology (1890), in which he developed a model of selfhood that resembled radiating spheres. At the centre was the ‘material self’, our bodies and material fortunes. This is frequently regarded as the most concrete aspect of our lives, but it is also, according to James, the most superficial. We would typically be willing to give up our material fortunes for the subsequent ring, what he terms ‘the social self’, the recognition that one gets from friends, family and loved ones. Finally, James explains, there is the ‘spiritual self’, one that is sought or experienced in ‘intellectual, moral, and religious aspiration’. This is the most expansive aspect of selfhood, the farthest reaching, but also, for many of us, the most subtle and easily neglected. This is the wave that matters even when it is not fully detected or articulated.

In the final decade of his life, James continued to defend the position that man could be the measure of all things. ‘I firmly disbelieve, myself, that our human experience is the highest form of experience extant in the Universe.’ The waves ripple out, strike the opposite shore, and make their way back – gently. Occasionally we feel them. On rare occasions, they are all we feel. It is a remarkable person, according to James, who can sense them deeply with any regularity. It is this type of unique individual who occupied much of James’s attention when he developed his Gifford Lectures in natural theology at the University of Edinburgh in 1901, a series of talks that became the Varieties of Religious Experience, published the following year.

James was never a churchgoing man. For the most part, he wasn’t interested in institutional religion or the doctrinal aspects of the spiritual self. He was, as always, interested in experience and life, and in his final years he began to turn explicitly to thinking through the religious possibilities of both. He refused to limit these possibilities, insisting in the Varieties:

Were one asked to characterise the life of religion in the broadest and most general terms possible, one might say that it consists of the belief that there is an unseen order, and our supreme good lies in harmoniously adjusting ourselves thereto.

This adjustment to the unseen order could take many forms and was never restricted to a particular church, temple or mosque. Indeed, James looked for it everywhere leading up to the writing of the Varieties. His exploration into the unseen carried him into experiments with psychotropic drugs but also into a spiritual realm that modernity often dismisses as mere quackery. Today, if something cannot be seen with perfect clarity, it seems easiest to assert that it cannot be seen at all.

When his aged father and newborn son died within a few years of each other, James and his wife Alice tried to contact them: in September 1885, James visited Leonora Piper, a medium who had become a Boston sensation for supposedly channelling spirits. He had his doubts about Piper but concluded that the woman might have what he called ‘supernormal powers’. James was still, and always, the consummate empiricist, and wanted to test these powers more carefully. Luckily, there was a fledgling organisation dedicated to precisely this study – James co-founded it in 1885.

He joked that James would turn down the lights in a room so that the miracles could happen

The mission of the American Society for Psychical Research was to investigate all things ‘supernormal’. This was not some fringe organisation, but it was not altogether normal, either. One of its co-founders, G Stanley Hall, had come to Harvard to do doctoral work with James in the late 1870s and was awarded the first psychology doctorate in the United States. With James’s support, Hall organised a group of researchers to explore the possibility of things such as spirit contact, divining rods and telepathy. They spent thousands of hours (I do not exaggerate) interviewing mystics and séance sitters. By 1890, Hall had resigned from the organisation, concluding that parapsychology amounted to pseudoscience. But others, like James and his close friend the physician Henry P Bowditch, marshalled on into the turn of the century. In 1909, James reflected on 25 years of ghostbusting:

I confess that at times I have been tempted to believe that the creator has eternally intended this department of nature to remain baffling, to prompt our curiosities and hopes and suspicions, all in equal measure, so that although ghosts and clairvoyances and raps and messages from spirits are always seeming to exist and can never be fully explained away, they also can never be susceptible of full corroboration.

Nature loves to hide. Humans like James love to seek. Despite the bafflement – or perhaps because of it – James and his fellow researchers remained pointedly, if cautiously, hopeful. Unlike most psychics of the time, however, the members of the psychical-research society documented and published their findings. None of those were anywhere near conclusive, but they did help to push the boundaries of science, exploring an area that science couldn’t quite explain. This record became the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, for members and close associates, and the Proceedings, intended for the general public. I’m always surprised by the sheer magnitude of the volumes: a little more than 17,000 pages in total. Somewhere between curiosity and suspicion was abiding hope.

When James began his psychical research, he was well ensconced in the field of physiology. However, the anatomist’s factual, objective method missed something in its understanding of human nature. For James, something important was lost: the sense that a human being is more than just a bundle of perceptions and nervous reactions, and more than just a body that could disappear without a trace. He hoped that there was something ethereal, transcendent – something even ghostly – that was free from the constraints of our physical lives. And at many times throughout his life, he suggested that one can occasionally feel this ‘something’ haunting the fringe of consciousness. As late as 1901, James remarked: ‘I seriously believe that the general problem of the subliminal … promises to be one of the great problems, possibly even the greatest problem, of psychology.’ ‘Subliminal’ is often used interchangeably with ‘unconscious’, but it shouldn’t be. It refers, instead, to mental processes just below the threshold of consciousness that can often be felt without fully emerging. Just a hint, a fleeting ‘maybe’, is all we get, but it is often enough to qualify as something that we know, at least for a moment. These glancing blows of experience stand at the centre of James’s Varieties – they come in many forms, indeed so many that their existence cannot be pushed aside.

The American jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes once joked that James would turn down the lights in a room so that the miracles could happen. I think that there is some truth in this. It is something like the American self-help author Wayne Dyer’s oft-repeated quote: ‘Miracles come in moments. Be ready and willing.’ James was definitely always ready and willing. When you turn the lights down, your pupils dilate so that more light can get in. You can’t blame James for this. Maybe we surprise ourselves with what we can see. And maybe that is miracle enough. ‘The miracle is not to walk on water,’ insists the Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh. ‘The miracle is to walk on the green earth in the present moment, to appreciate the peace and beauty that are available now.’ For secular skeptics, this might be as far as they are ever willing to go when it comes to religious experience: to dwell deeply, to ‘live a little’ in the present. James, however, goes just a little farther, a little deeper, in the Varieties.

Sometimes, when you turn the lights very low, you can see things more clearly. James describes such a phenomenon, the only one, he claimed, that could be called genuinely ‘mystical’. Recounting the ‘hour of rapture’ of a clergyman, James writes:

The perfect stillness of the night was thrilled by a more solemn silence. The darkness held a presence that was all the more felt because it was not seen. I could not any more have doubted that He was there than that I was. Indeed, I felt myself to be, if possible, the less real of the two.

The ‘He’, according to the clergyman, was undoubtedly the Judeo-Christian God, but what we call this presence scarcely mattered to James. ‘He’ is a very old word, older than gender and sex, meaning ‘this here’. ‘This here’ was present, all the more felt, because it wasn’t seen. For James, for his fellow mystics such as Blood, there was a sustained comfort in this story. As the German mystic Novalis wrote: ‘We are more closely connected to the invisible than to the visible.’ This too is a possibility, and the Jamesian pragmatist is happy to entertain it.

Before the Brooklyn Bridge was built, a ferry carried passengers from one side of the river to the other. Walt Whitman was often among the crowd. The American poet was one of James’s longstanding heroes, the embodiment of the capacious ‘healthy mind’ he describes in the Varieties. James occasionally sensed the sublime or the religious on his hikes in the Adirondacks or in the testament of mystics, but Whitman could tap into it on a routine basis, even on a dirty ferry ride, which most people would regard as a rather annoying commute. It wasn’t annoying for Whitman. In his poem ‘Crossing Brooklyn Ferry’ (1855), he described the spectacle – the experience of nature and the experience of the human throng. Both were inexplicable and hopeful and shared:

Others will enter the gates of the ferry, and cross from shore to shore,

Others will watch the run of the flood-tide;

Others will see the shipping of Manhattan north and west, and the heights of Brooklyn to the south and east;

Others will see the islands large and small;

Fifty years hence, others will see them as they cross, the sun half an hour high.

A hundred years hence, or ever so many hundred years hence, others will see them,

Will enjoy the sunset, the pouring in of the flood-tide, the falling back to the sea of the ebb-tide.

3.

It avails not, neither time or place – distance avails not.

James read and reread this poem. This was wonder, and there was enough of it to go around. It turns out that one can probably set aside the nuttier aspects of the Society for Psychical Research and still retain a Whitman-esque experience of the world, the numinous immanence of an all-too-human ferry ride. That, at least, was James’s hope. Whitman’s vision, in James’s words, was sufficient ‘to prompt our curiosities and hopes and suspicions’. The world is not always, or ever, exactly as it seems. A dirty ferry ride might be more than just a dirty ferry ride. There is something more – at least it is possible. Whitman’s was a type of religious experience – and so very different from the way that most people experience the world. Reflecting on ‘Crossing Brooklyn Ferry’, James explained:

When your ordinary Brooklynite or New Yorker, leading a life replete with too much luxury, or tired and careworn, about his personal affairs, crosses the ferry or goes up Broadway, his fancy does not thus ‘soar away into the colours of the sunset’ as did Whitman’s, nor does he inwardly realise at all the indisputable fact that this world never did anywhere or at any time contain more of essential divinity, or of eternal meaning, than is embodied in the fields of vision over which his eyes so carelessly pass.

However, one does not have to be careless. Thankfully there are other ways to pass the time and other times to pass away. The flood and the ebb continue to go out and come in. And James suggests that it is possible, even for a pragmatist, to occasionally feel the reassuring cycle of its flow. At these moments, one has a chance to be ‘religious’ in James’s sense of the word, to enter ‘a state of mind, known to religious men, but to no others, in which the will to assert ourselves and hold our own has been displaced by a willingness to close our mouths and be as nothing in the floods and waterspouts of God. In this state of mind, what we most dreaded has become the habitation of our safety …’

I looked out to the Statue of Liberty again, and back down into the water below. The sun was indeed setting, and I tried to let myself watch it, as Whitman and James hoped we would, for what seemed like many minutes. Just long enough to be glad that I still had the chance.