Causal understanding is the cognitive capacity that enables you to think about how things affect and influence each other. It is your concept of making, doing, generating and producing – of causing – that allows you to grasp how the Moon causes the tides, how a virus makes you sick, why tariffs change international trade, the social consequences of a faux pas, and the way each event in a story leads to what happens next. Causal understanding is the foundation of all thoughts why, how, because, and what if. When you plan for tomorrow, wonder how things could have turned out differently, or imagine something impossible (What would it be like to fly?), your causal understanding is at work.

In daily life, causal understanding imbues your observations of changes in the world with a kind of generativity and necessity. If you hear a sound, you assume something made it. If there’s a dent on the car, you know that something – or someone – must have done it. You know that the downpour will make you wet, so you push the umbrella handle to open it and avoid getting soaked. You watch as an acorn falls from a tree, producing ripples in a puddle.

The human power to view cause-and-effect as part of ‘objective reality’ (a philosophically fraught idea, but for now: the mind-independent world ‘out there’) is so basic, so automatic, that it’s difficult to imagine our experience without it. Just as it’s nearly impossible to see letters and words as mere shapes on a page or a screen (try it!), it is terrifically challenging to observe changes in the world as not involving causation. We do not see: a key disappearing into a keyhole; hands moving; door swinging open. We see someone unlocking the door. We don’t see the puddle, then the puddle with ripples-plus-acorn. We see the acorn making a splash.

Most people don’t realise that any of this is a cognitive achievement. But, in fact, it is highly unusual. No other animal thinks about causation in the hyper-objective, hyper-general way that we do. Only we – adult humans – see the world suffused with causality. As a result, we have unparalleled power to change and control it. Our causal understanding is a superpower.

The scientific story of how our causal minds develop features another superpower: human sociality. It’s our unique sensitivity to other people that lets us acquire our special causal understanding. The story also raises questions about ‘other minds’. If our causal understanding is the exception, rather than the rule, then how does the world show up for other animals? If we try to suspend the causal necessity that structures so much of our experience, what’s left over?

I’m going to suggest that what remains is our experience of doing – a value-laden, first-personal and inherently interactive perspective. It is in this involved, participatory ‘point of do’ – as opposed to a detached, objective point of view – that the seeds of higher cognition take root. Appreciating that our original perspective is action-oriented and goal-directed can also help us understand our own shortcomings – and how to change them.

Psychological research on causal understanding is widely guided by a framework called ‘interventionism’. Think of two changes that happen together. The sun comes up, and the rooster crows. Did the sunrise cause the crowing, or did the rooster cause the sunrise? This isn’t hard to decide. But, as with many philosophical endeavours, the apparently simple truth becomes hard to spell out once you try. (What do you mean, the sunrise ‘causes’ the rooster to crow? ‘Well, I guess the sunlight activates the rooster’s circadian rhythm, or something.’ What do you mean, ‘activates’? ‘Um, I don’t know exactly… it does something to hormones, maybe–’ What do you mean, ‘does something to’? ‘Uhh… sets off? Triggers? Generates?’ But what is ‘setting off’, ‘triggering’, ‘generating’…?)

Interventionism offers a neat way of defining ‘cause’ that helps to structure the concept. There are two steps. First, causes and effects are thought of as variables with values that can change. The sun’s position can have the value ‘up’ or ‘down’; the rooster’s vocalisation can be ‘crowing’ or ‘not crowing’. Second, a causal relation is defined in terms of interventions – targeted changes. Imagine keeping everything the same and changing only whether the sun comes up. If it didn’t come up, would the rooster still crow? Now try the opposite: if the rooster stayed quiet, would the sun still rise?

Changing the sun changes the rooster, but changing the rooster doesn’t change the sun. So the sun is the cause, and the crowing is the effect.

This interventionist way of defining causation is often referred to as ‘difference-making’. That’s because a ‘cause’ is something that makes a difference to something else: wiggle the cause, and the effect wiggles, too. This doesn’t fully satisfy our sceptic – (What do you mean, difference-MAKING?) – but it does give us a more precise way of talking about causal relations. As the sun-and-rooster example shows, the interventions don’t have to be actually possible. The key idea is simply: if we were to change the cause, then it would make a difference to the effect.

Interventional learning is learning by doing. It results in causal knowledge, and it gives us the power to control

Another way to think about causal understanding is to appreciate the difference between prediction and control – or the difference between statistical and interventional learning.

Consider the following sequence: #@mb!#@mb!#@mb!#@mb…

What comes next?

How about: red red green green purple purple blue…

What’s the next word?

Humans and other animals excel at picking up on patterns. This is statistical (or associative) learning, and it results in statistical knowledge – knowledge of correlations. We do this passively and automatically, and it gives us the power to predict. Think of statistical knowledge like hearing a familiar song on the radio: you just know what comes next, without trying.

Interventional learning, by contrast, is active learning – learning by doing. It results in causal knowledge, and it gives us the power to control.

Here’s a scenario to illustrate. Imagine you’re standing at the entrance of a hardware store, leaning against the door while you wait for me to pay. (If it helps: I’m a mid-30s white lady with pink hair.) You watch cars go by in the street. Behind you, people chat to each other in the line. From time to time, a bell rings. You step back as someone bustles past with a pallet of plants.

‘Hey,’ I say, finally coming over. ‘Why are you ringing that bell?’

‘What do you mean?’ you reply. ‘I’m just standing here.’

‘That bell!’ I say, pointing above your head. Sure enough, there’s a small bell attached to the door you were leaning on.

‘I didn’t know I was ringing it!’ you say. But you try moving the door back and forth, and it’s true: moving the door makes the bell ring, and it was moving a bit as you leaned.

The scene we’ve just imagined comes from a vignette in Intention (1957) by the philosopher G E M Anscombe. In her analysis, ‘actions’ are the kind of thing to which a special sense of the question ‘Why?’ applies – specifically, the ‘Why?’ we address to people when enquiring about their aim, goal or purpose (Why are you ringing that bell?) When you rang the bell without knowing it, Anscombe says, that wasn’t an action. But when you moved the door to make it ring – when you knew what you were doing – then it was.

The development of causal understanding depends precisely on this ‘insider perspective’ on your own actions – your knowledge of your goal, the thing you’re aiming at by acting.

I’m going to call this: your point of do.

Many animals have a point of do. They readily learn cause-effect relations between actions (like pushing a lever) and desired outcomes (like receiving food). But their causal learning is typically restricted to specific contexts and short timescales. If a pigeon learns that pecking a lever produces food from a feeder, they will likely need to re-learn this in a new setting. Introduce a delay between pecking and feeding, and they won’t catch on, either.

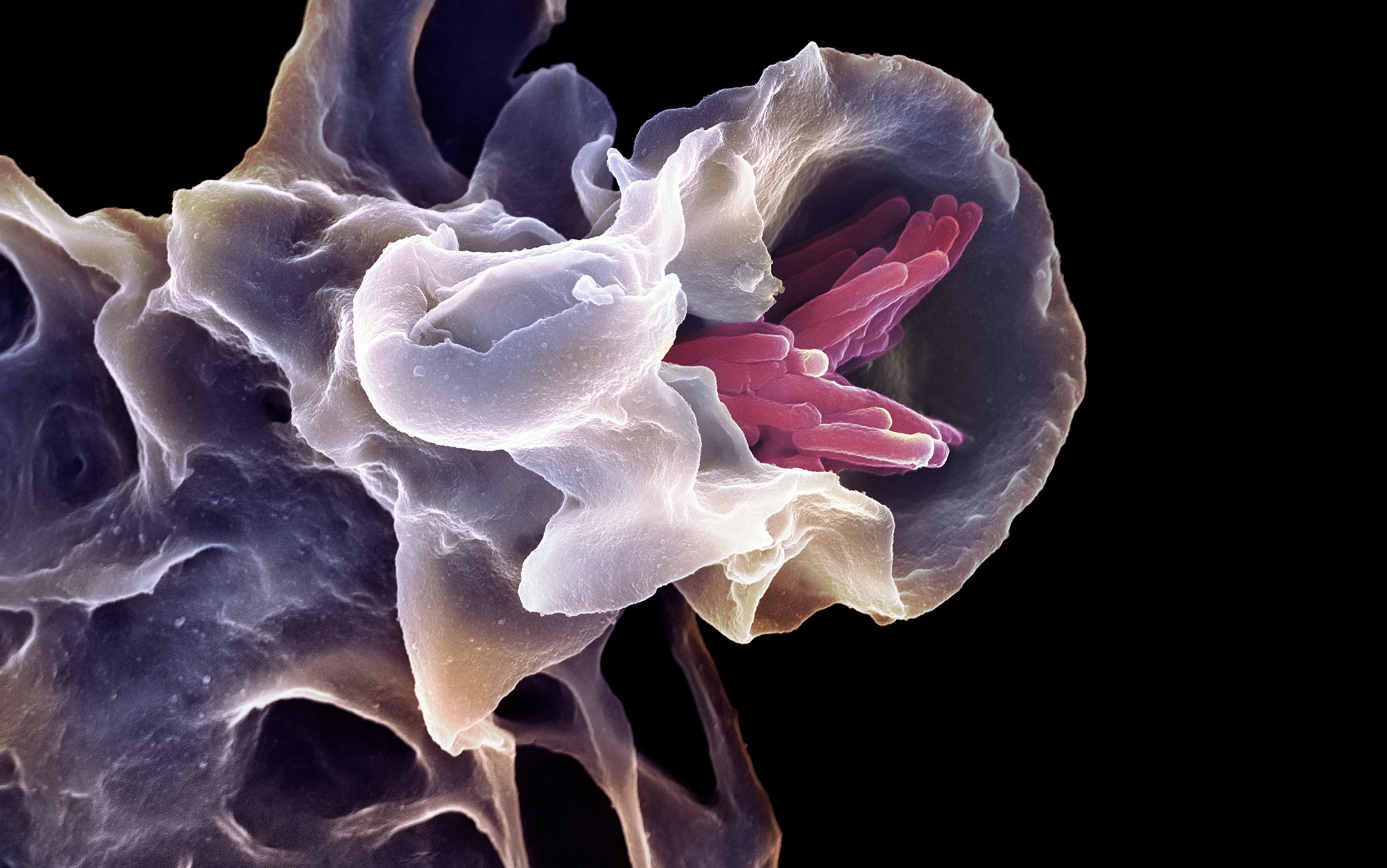

Nonhuman animals’ causal understanding is largely egocentric. It is ‘I-’, or ‘me-causation’ – limited to the changes their own actions generate, and dependent on goals that lock attention onto specific variables. Even clever nonhuman animals like apes, rats and crows will typically learn causal relations only if they are actively seeking a reward (like food) or avoiding a punishment (like a shock). When an inanimate object, another animal’s activity or even their own accidental movements cause the effect, they typically won’t learn the relation.

That said: there’s some evidence that apes can learn some causal relations by watching others. But humans are in a league of our own. By three months old, infants seem to have not only first-personal, ‘me-causal’ understanding, but also third-personal, ‘they-causal’ understanding. Because we constantly interpret other people’s movements as goal-directed actions, we see the causes they manipulate and the effects they aim to generate as manipulable and producible for us, too.

In the first eight to 12 weeks of life, infants’ ‘me-causal’ understanding allows them to cry in targeted ways to attract attention and learn to make a mobile move by kicking their feet. They also learn that cooing and making faces causes responses from their caregivers – something other primates don’t seem to do. By nine months, ‘they-causal’ understanding shows up in full force. Infants can imitate others’ actions on a toy, such as pressing a button to make a sound. At 14 months, they can replicate unusual actions they’ve never tried, like using their head to turn on a light.

Interacting, observing and labelling constantly pull new causal variables and relations into children’s awareness

By toddlerhood, children generalise causal relations from others’ actions. If they see that someone who places a red triangle block on a machine causes music, but placing a blue triangle does not, they’ll select a (novel) red square block to activate it themselves. They also pick up causal words that generalise across situations. A toddler may use ‘allgone’ to refer to the effects of diverse actions – such as popping a bubble, finishing a bottle, or searching for a toy that isn’t there.

These social activities – interacting, observing and labelling – constantly pull new causal variables and relations into children’s awareness. The effect is a kind of constant attentional highlighting – like pointing out the bell on the door. (Do you see that thing over there? Look, you can control it!) In some cultures, adults also spontaneously offer causal explanations. (Eating broccoli makes you big and strong. Let’s put the cake in the oven to make it fluffy! Do you remember why we don’t run down the slide? What happened last time?)

The diversity, generality and sheer number of causal relations that even a two-year-old can grasp applies to more domains and longer timescales than nonhuman animals ever learn. Interacting with artefacts – from rattles to light switches to iPads – probably also facilitates a sense of ‘possible causes everywhere’, a world open for manipulation. It’s as if the social environment sets us up to think: What can I do? What can I do? What can I do?

But there’s an interesting limitation. Until about age four, children’s causal understanding remains tightly tied to their own and others’ goal-directed actions. In one study, two-, three- and four-year-olds watched as a toy car moved toward a wall. When it arrived, a pinwheel rotated some distance away. Children of all ages showed statistical learning (prediction): after a while, they looked toward the pinwheel when the car approached.

The revealing finding surfaced when experimenters varied two things: first, how the car moved and, second, how children behaved when asked to produce the effect themselves. Some children saw a person push the car to the wall. In this case, when told it was ‘their turn’ to make the pinwheel go, kids of all ages replicated the action. But things were different if they saw the car move by itself. Here, only the four-year-olds reliably grabbed the car and touched the wall to spin the wheel.

It’s unclear exactly what drives the development of impersonal, ‘it-causal’ understanding – the shift from a causal understanding grounded in actions to an objective one where causality is seen as part of the world itself. (This is the causal understanding that makes you look up at the tree above your car to check if an acorn could have caused the dent.) However, around age four, children also develop ‘theory of mind’ (appreciating that people’s beliefs can fail to match reality), visual perspective-taking (understanding that something that’s blue for me will look green to you wearing yellow glasses), and tolerate ‘dual naming’ (you say tree, I say bush; we can both be right). Notably, these all involve holding two ideas about the same thing in mind at once. Perhaps the idea of ‘causal potential’ that persists even when no one is changing things requires ‘dual representation,’ too.

Whatever the ultimate cause of humans’ uniquely general and impersonal causal understanding, it’s clear that other animals perpetually inhabit the ‘me-causal’ perspective – the point of do. They never achieve the objective point of view where causation is part of everything.

How does the world show up for them? Here’s how I think about it. When you watch a 3D movie, wearing 3D glasses makes objects ‘pop out’. Through the lens of ‘me-causation’, I imagine a kind of rustic control panel – a wilderness equivalent of levers, switches and dials. A stick might pop out as a means for retrieving an out-of-reach fruit. A long blade of grass might pop out as a tool for extracting a meal from a termite mound.

But these ‘intervenable’ props for action would be sparse. And they would mainly appear in situations very similar to others where you had acted before. Everything else would be mere variation – like shifting forms on a laptop screensaver. Some changes would be benign (rippling grass in a windy field). Others might have valenced associations – like a sudden rustling in the bushes (‘uh-oh!’), the calls of distant conspecifics (‘friends!’), or the musk of a potential partner (‘ooOOh!’). But these percepts, patterns and rhythms would be a kind of Humean music: familiar, predictable and reliable, but not caused, controllable or explainable.

Here’s another way to think about it. As a newborn, before your mind was transformed by social learning and language, you were ensconced in meaningful settings, each with their own meaningful tendencies. In your crib, the (captivating) mobile above you tended to sway. In the sink for a bath, the spout tended to shhhhh. There was thick wetness around you and smoothness beneath you. Parents – blurry through your not-yet-developed eyes – tended to move in many directions, put good things in your mouth, whisper, rock you, and hold you close.

Nonhuman action is characterised less by control and more by something like cooperation

Simultaneously – guided by events that you valued – you discovered your agency. Smiles happen more when I smile myself (AMAZING!) Clutching the blanket and moving my arm makes me cold (TERRIBLE). Smashing peas changes their shape (FASCINATING! LET US REPEAT). Through interaction, the world opened itself to you, coming into focus as a field of possible doings.

There’s another thing to note. Human environments are set up – by us – to seamlessly support manipulation and control. You live in a world of flat surfaces, doorknobs and other ‘equipment’ (to use a word from Martin Heidegger). Not so for other animals. Orangutans spend much of their time in the dense forest, negotiating with branches. Some can be pushed away, others snap back, and others can’t be moved at all – you have to go around. An artic seal labours with teeth and claws to make holes in hard, unforgiving ice. An albatross skilfully aligns their body with wind currents that speed their glide but it cannot control them.

Nonhuman action is characterised less by control and more by something like cooperation. It’s an existence where ‘doing’ means working with the environment, not dominating it. Acting is like the Serenity Prayer: Grant me the serenity to accept the things I can’t change; courage to change the things I can; and the wisdom to know the difference. Think of swimming in the ocean when a big wave comes. You can decide whether to go over or under. But you can’t try to stop it – you have to go with the flow.

This worldview was once ours, too. Before the world appeared to us as manipulable and controllable, ripe to be bent to our will, it was dynamically present. It was there as a push – sometimes in support, and sometimes in opposition. It was a force to be reckoned with, demanding consideration in our doings.

This is what our superpower lets us overcome – and forget.

When I think about human causal understanding, I often think of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. It’s an animated short from Disney’s musical anthology Fantasia (1940), based on an eponymous poem by Goethe. Mickey Mouse – dressed in a blue wizard hat and red robes – is a mischievous sorcerer-in-training. He steals his teacher’s spell book and bewitches a broomstick to do his chore: filling up a cauldron. The broom sprouts arms, picks up Mickey’s buckets, and starts marching around. It fetches some water and empties it into the cauldron. Then, it does it again… and again. And again. The cauldron overflows, and Mickey panics. He chops up the broom with an axe – but each magical splinter transforms into a broomstick itself! Soon, there’s a whole army of brooms filling the cauldron. When the sorcerer finally rescues him, Mickey is clinging to the spell book, rafting around in a flood.

Our causal understanding is the foundation of science and engineering. It has given us plumbing, electricity and sanitation; bicycles, tunnels and rockets; vaccines and chemotherapy. It’s the basis of social technologies like moral accountability, trade agreements and traffic laws. It lets us plan, tell stories and imagine new possibilities. But it can be a dark magic, too. Our immense power to manipulate our physical and social environments has produced the industrial pollutants transforming the climate; the microplastics seeping into our brains, testes and breastmilk; factory farms and toxic pesticides; addictive processed food; drugs of abuse; weapons of mass destruction; and algorithms expressly designed to manipulate your decision-making and attention.

We can use our causal understanding to intervene in our own behaviour

Our collective capacity to make new choices about what to do with all our power will determine the fate of our species. The thing that’s so scary and frustrating and hard is that it seems out of our control. It’s bigger than any one of us – far beyond the scale of goal-directed action we evolved to consider.

Here’s why I’m hopeful. I think we can use our causal understanding to intervene in our own behaviour. For one, we know that it’s highly flexible. Even primary school children can learn about the complex causal relations involved in ecosystems, food chains and structural inequality – this can provide guidance for education, storybooks and children’s media. We also know about the power of sociality – the power of highlighting variables for one another. Friends and family are an influential source for developing habits around causal factors that affect our own health (like exercise, diet and microplastics) and the planet’s (like eating meat, composting and sustainable consumer practices). The more we talk to each other about these difference-makers, the more these actions can echo and amplify, species-wide.

Finally, causal understanding is rooted, originally, in our values – things we want. The most primal causal learning happens by aiming at things we want to make happen. This means that optimistic, action-oriented suggestions are probably more effective than doom and gloom. My favourite recent instance of human causal imagination is the book What If We Get It Right? (2024) by the marine biologist and climate activist Ayana Elizabeth Johnson. In it, Johnson invites us to imagine the future we want to live in, and shoot for it – each in our own way, in our own communities. We already have a lot of solutions, she says; we just need to scale, spread and use them.

With that in mind, I think there’s hope. It’s only a small step from What if we get it right? to What can I do?

Let’s get doing!