A note from Manjula Menon: My husband Anand Vaidya died on 11 October 2024, from complications due to cancer. He was only 48, yet had already carefully forged multiple trails through the contemporary philosophical landscape. He did philosophy till the end, leaving behind detailed book proposals, carefully drawn drafts of papers, and numerous abstracts and proposals for projects yet to be written, from which we can trace where he wanted to go with his scholarship. This essay was the last piece he actively worked on, one that I helped shape when he was already very sick. If we hadn’t run out of time, I believe he would have liked to include here further arguments for how notions of self from classical Indian thinkers could shed light on the ‘hard problem’ of consciousness. It was an idea on which he had already done substantial work, and I am grateful to his many friends and colleagues who are helping ensure that his efforts do not go to waste. For this piece, I am particularly grateful to Jonardon Ganeri who generously helped finalise the article after Anand was no longer able to. I am also grateful to Sam Dresser and the team at Aeon for shepherding this through. It would have meant a lot to Anand to see it.

The Kaṭha Upaniṣad tells a story about a boy named Naciketas who meets the God of Death, named Yama. Naciketas is granted three wishes by Yama. To Yama’s surprise, the boy does not ask for worldly riches or great powers. Instead, he wants answers to the kind of questions that only the God of Death can answer: what happens when we die? What is the secret of immortality? Yama pleads for Naciketas to ask for something else, but the boy stands firm. He demands that Yama not renege on his word. Nothing that Yama can say will change his mind. So Yama complies.

To answer Naciketas’s questions, Yama explains that the true hidden nature of reality is that there is only one, all-pervading consciousness called brahman, which is timeless, unchanging and the only non-illusory thing that was and ever will be. And it is this brahman, says Yama, that is also immanent in all living things as ātman, the individual ego or self:

As the single fire, entering living beings, adapts its appearance to match that of each, so the single Self within every being adapts its appearance to match that of each, yet remains quite distinct. [This and subsequent translations are the authors’ own.]

Naciketas presses Yama for clarity about the nature of the relationship between brahman and the world of experienced reality. Yama says that the way to think of consciousness is that it is the thing that ‘illuminates’ and that allows for all mental phenomena. Consciousness, in turn, is itself illuminated by brahman – the one and only source of all illumination. Without brahman there would be no light of consciousness and therefore no experience, no knowledge, no perception. ‘Him alone, as he shines, do all things reflect; this whole world radiates with his light.’

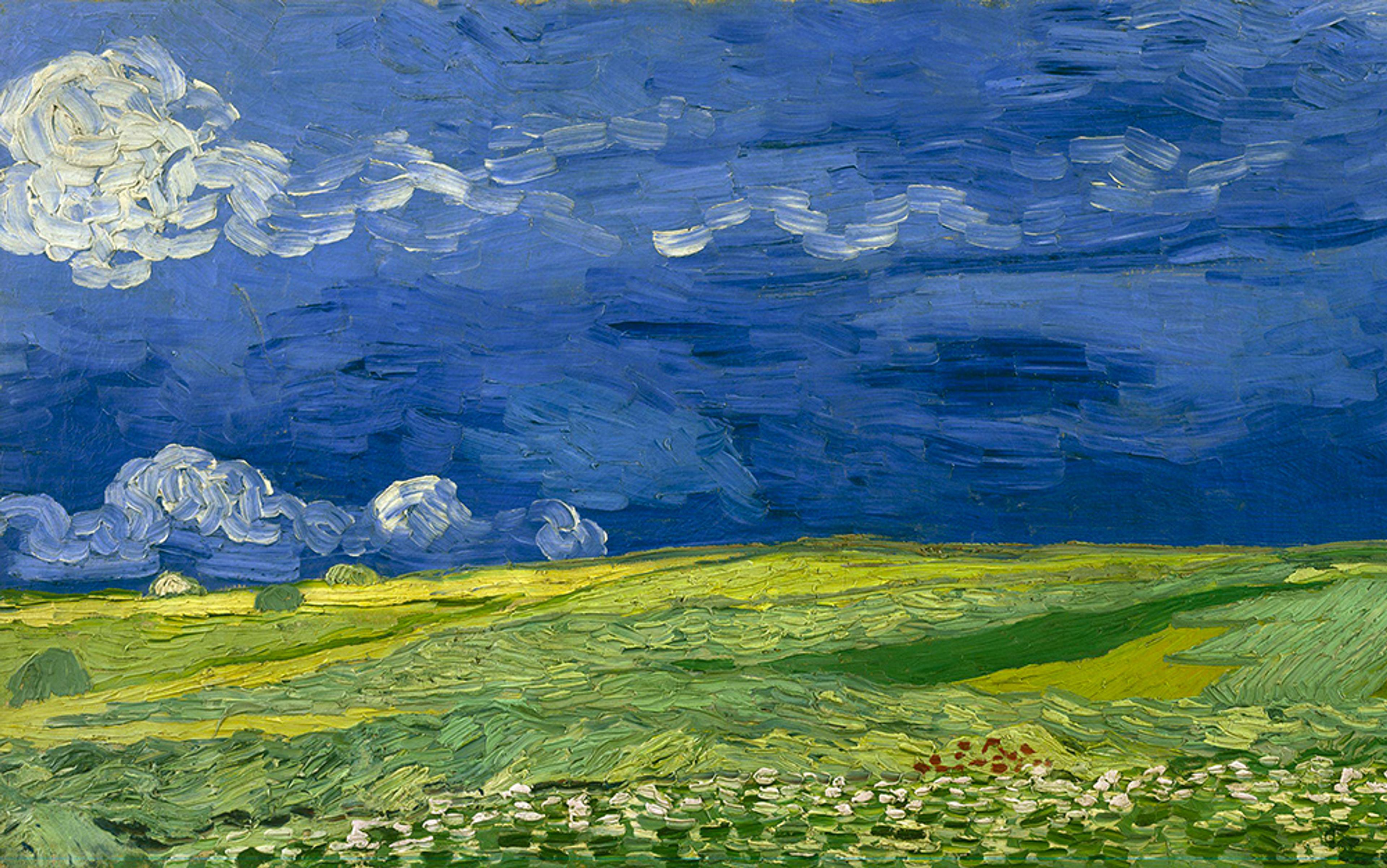

There is only one reality, brahman, which takes myriad illusory forms, but like fire it is both an individual flame and a blaze. This one reality is both the transcendental brahman and the immanent ātman. Everything else is fleeting, illusory, sprung from ignorance. Consciousness is illumination. As the light of a blazing lamp brightens a dark room, so consciousness lights up life.

What does it mean to say that consciousness is illumination? (The Sanskrit word is prakāśa, sometimes rendered as ‘manifestation’.) We aim to enquire here whether notions like this, drawn from classical Indian philosophy, could be applied to debates about the nature of consciousness in contemporary analytical philosophy of mind.

In contemporary analytic philosophy, it is typical to see a separation between discussions of the self and discussions of consciousness. For example, Derek Parfit writes at length about the self, little about consciousness. David Chalmers writes at length about consciousness, little about the self. There are exceptions: both Galen Strawson and Daniel Dennett write both about the self and about consciousness. In Indian philosophy, discussions of the self, consciousness and reality are carried out alongside each other. All the major thinkers turn to the nature of the self, reality and consciousness, often to tell a story about how to reduce suffering.

At, or at least near, the centre of contemporary analytic philosophy of mind is the ‘hard problem of consciousness’, coined by Chalmers in his seminal paper ‘Facing up to the Problem of Consciousness’ (1995). To the hard problem, he contrasted what he called ‘the easy problems of consciousness’:

The easy problems of consciousness are those that seem directly susceptible to the standard methods of cognitive science, whereby a phenomenon is explained in terms of computational or neural mechanisms.

After offering examples of ‘easy’ problems of consciousness, including the ability to discriminate between stimuli, to create and access memory and to report on internal mental states, he goes on to characterise the ‘hard’ problem:

The really hard problem of consciousness is the problem of experience … How can we explain why there is something it is like to entertain a mental image, or to experience an emotion?

The kind of consciousness being described is phenomenal. That is to say, it has to do with the felt quality of experience. Consciousness has a ‘what it is like for me’ aspect that is accessible both through phenomenal contrast (eg, seeing blue vs red), and subject contrast (eg, the experience of Anand vs that of Manjula). It is typically the phenomenal component that comes along with what the German philosopher Franz Brentano referred to as intentional states.

The hard problem emerges when we try to explain what it’s like to have a conscious experience of a tree

Drawing on the work of medieval scholastic philosophers, Brentano argued in his Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint (1874) that all mental phenomena is directed, is about something. Indeed, there cannot be a mental state without that state having an object. Whether one is thinking about how to analyse a tree, or admiring the way sunlight sifts through its branches, listening to the sound of its leaves shaking, or even experiencing an uplifted mood due to its mere presence – all of these mental phenomena are in reference to something: the tree. As Brentano put it: ‘There is no hearing unless something is heard, no believing unless something is believed; there is no hoping unless something is hoped for.’ This intentional or referential quality is what defines all mental phenomena and separates mental states from the physical objects in the world.

The hard problem of consciousness emerges when we try to explain scientifically the phenomenal aspect of intentional states – what is it like to have a conscious experience of a tree? To distinguish the hard problem of consciousness, the feeling associated with being conscious in the world, from easy problems like reasoning and taking accordant action, Chalmers offers a thought experiment.

First, he asks that we posit the existence of ‘zombies’, which are creatures that are like us in every way, except that they lack phenomenal consciousness. Zombie-Chalmers, for example, is a physical duplicate of Chalmers that lives in a physical duplicate world of ours, but for which there is no phenomenal consciousness. If zombie-Chalmers is conceivable, that is, if there is no contradiction in the idea of a physical duplicate of Chalmers that lacks phenomenal consciousness, then Chalmers argues that we have prima facie evidence for thinking that zombie-Chalmers is metaphysically possible. And if zombie-Chalmers is metaphysically possible, then that, allegedly, proves that something other than the physical exists in our world.

Does prakāśa or ‘illumination’ have anything to say about the hard problem of consciousness? We think it might. But first we need to explore some foundational ideas in classical Indian philosophy.

The classical Indian philosophical tradition is usually – if somewhat misleadingly – classified as comprised of the five sub-schools of Vedic Hinduism and three schools outside of it (Buddhism, Jainism, Cārvāka), each representing a long lineage of scholars who argue in favour of different notions of metaphysics and epistemology. We will focus on ideas from one of the Vedic schools, the Vedānta, which builds atop three foundational corpora: the Upaniṣads, the Brahma-sūtra and the Bhagavad-gītā. We will focus on two figures within the broadly construed Vedānta tradition, the singularly influential 8th-century philosopher Śaṅkara, and one of his interlocutors, the 11th-century philosopher Rāmānuja.

For a flavour of the kind of things classical Indian philosophers thought about, we will begin with a bird’s eye view of a few notions from classical Indian philosophy, with the caveat that every idea described below has been hotly debated for hundreds of years.

Central to Indian philosophy is the idea of illusion. Here, there is a distinction between temporal and presentational notions of illusion. The first holds that whatever is not permanent in time, or else beyond time, is thereby an illusion. Of the various schools of Indian philosophy, Buddhism and Advaita Vedānta agree in accepting this account. The second notion holds that whatever is presented to a subject of experience as other than how it is, is an illusion. This notion derives from the school of Nyāya, its early proponents from the 1st millennium and the work of the 14th-century philosopher Gaṅgeśa, considered to be the founder of the New Nyāya movement.

With talk about illusion, of course, comes talk about reality. And here the classical Indian philosophers made a number of fine distinctions. For our purposes, three are of note: conventional reality, apparent reality, and ultimate reality. Conventional reality just means everyday reality, one that is based on the pragmatics of everyday life under societal conventions and laws. Think of money, or the game of chess. Apparent reality is the notion of a reality that depends on our sensory organs of perception and the machinations of the mind: what we see is a tree and not an aggregate of organic molecules. Finally, ultimate reality is the notion that there is an underlying or hidden substratum to the world. Advaita Vedānta, for example, holds that brahman is identical with this ultimate reality.

This is the self as what is permanent in time; it is sometimes expressed by the word soul

The other great Indian topic we’ll be concerned with is the self. The self is frequently understood in five different aspects. The first three are often also explored in contemporary Western philosophy of mind: the self as what makes decisions, engages in rational activity, and enables action; as what can gain and lose knowledge over time; and as what experiences in the ordinary empirical world. These three notions of the self might encompass what William James, in the chapter ‘Consciousness of Self’ from The Principles of Psychology (1890), called the ‘empirical self’, which he defines thus: ‘The Empirical Self of each of us is all that he is tempted to call by the name of me.’ James contrasted the notion of the empirical self with the more subtle, transcendent ‘pure’ self.

The fourth aspect is perhaps what some would call more ‘spiritual’ – and which we simply define here as a subjective and usually ineffable experience of something venerable and greater than oneself. This is the self as what is permanent in time, and what undergoes transmigration from one body to another through karmic rebirth; it is sometimes expressed by the word soul. The fifth aspect is the self as the individual manifestation of a universal and single foundational consciousness (brahman). And here we return to Yama’s lesson.

Śaṅkara offers an analogy about how to understand all this. He compares brahman to a tree:

Its roots above, its branches below, this is the eternal banyan tree. That alone is the Bright! That is brahman! That alone is called the Immortal! On it all the worlds rest; beyond it no one can ever pass.

He goes on to focus on the illusory nature of experience in his accompanying commentary:

It is a tree, so-called because it is felled; this tree consisting in manifold miseries of birth, decay, death and grief, changing its nature every moment … the subject of several doubtful alternatives in the intellects of many hundreds of sceptics … growing from the seed of ignorance … having for its trunk the various subtle bodies of all living things … having for its tender buds the objects of intelligence and the senses, having for its leaves the logic, learning and instruction … having various tastes such as the experience of joy and sorrow, having endless fruits on which living beings subsist, with its roots entwined and fastened firm by the sprinkling of the waters of desire … reverberating with the tumultuous noise arising from dancing, singing, instrumental music, joking … induced by mirth and grief, produced by the happiness and misery of living beings and felled by the unresisted sword of the realisation of the highest Self proved by the Vedānta, this tree of saṃsāra always shaking by its nature to the wind of desire …

The idea that the only foundational reality is brahman, and that all else is presentational illusion, does not go unchallenged. The philosopher Rāmānuja disagrees with Śaṅkara on almost all the key points. He makes the following argument. First of all, foundational reality cannot consist in the existence of a single hidden and purely phenomenal consciousness, as per Śaṅkara, because the subject-object dichotomy is an inherent attribute of all mental phenomena. (This point anticipates Brentano.) Moreover, our everyday perception of the world cannot be fundamentally illusory (again, as per Śaṅkara) but must be said to accurately represent reality if we want to claim to understand anything about the world at all. Finally, there is no coherent reading of the foundational texts without invoking the idea of a transcendental God, one wholly and fundamentally different from everything else. Therefore, Śaṅkara’s monism is false to the textual tradition.

What is really at stake here is the question of the very nature of consciousness as ‘illumination’

Incidentally, somewhat later, the French philosopher and polymath René Descartes would employ similar reasoning to argue in favour of a dual conception of reality in his Meditations on First Philosophy (1641), viz that there are two fundamentally different kinds of things in the world, mind and matter, with God being distinct from both.

While the prevailing view is that Rāmānuja’s most important contribution to Indian philosophy is his defence of theism, his arguments against illusionism and monism are more interesting when it comes to contemporary debates in the philosophy of mind, and the contribution that Indian philosophy can make to them. What is really at stake here is the question of the very nature of consciousness as ‘illumination’ (prakāśa).

For Śaṅkara, the relevant sense in which consciousness consists in ‘illumination’ is not a matter of what is thereby illuminated or revealed, but that ‘illumination’ is what allows for the revealing to occur in the first place. It is not just another object in the world but the very condition for the appearance of objects. As Wolfgang Fasching insightfully puts it in 2021:

[Śaṅkara] insists on the ontological uniqueness of consciousness: it is fundamentally different from anything we ever encounter as an object of consciousness, as different as ‘light’ is from ‘darkness’, as Śaṅkara says in the initial statement of his Brahmasūtrabhāshya.

So, as Fasching continues, for Śaṅkara,

[C]onsciousness is to be distinguished from all contents of consciousness that might be introspectively detectable: it is precisely consciousness of whatever contents it is conscious of and not itself one of these contents. Its only nature is, [Śaṅkara] holds, prakāśa (manifestation); in itself it is devoid of any content or structure and can never become an object.

For Rāmānuja, on the other hand – and this is key to his disagreement with Śaṅkara – consciousness is not an abstract, contentless, structureless illumination, but is always tied to objects and to individual selves (jīva). Rāmānuja maintains that consciousness is relational. It has both content and structure.

Let’s loop back now to the hard problem of consciousness, the problem that so preoccupies contemporary analytical philosophy of mind. How are we to explain the felt phenomenology of conscious experience? One increasingly popular attempt to find a solution to the hard problem lies in some form of panpsychism. Panpsychism is the notion that consciousness is already everywhere and in everything, or at least is already a fundamental building block in the Universe. It has deep roots within Western philosophy, stretching back to pre-Socratic Ionian philosophers, including Thales, who lived in the 5th-6th century BCE. While the popularity of panpsychism as a doctrine has peaked and ebbed over the millennia, it is currently experiencing a renaissance in contemporary analytical philosophy.

Strawson, for instance, defends a ‘micropsychism’ that posits micro-conscious entities at the fundamental level to explain macro-conscious entities such as humans. This version of panpsychism must face up to a combination problem: that is, it must explain just how micro-conscious entities combine to form macro-conscious entities. Currently, there is no agreed solution to this problem of combination. Philip Goff therefore instead defends ‘cosmopsychism’, which aims to move away from the underlying atomistic metaphysics of micro-conscious entities to an underlying non-atomistic metaphysics of universal consciousness: it is the cosmos as a whole that is fundamentally conscious. But cosmopsychism has its own recombination problems to face: how do we get from a single all-pervasive universal consciousness to individual consciousness at the level of individual human organisms, each with its own unique first-personal perspective on the world?

Contemporary solutions to the hard problem of consciousness often claim that phenomenality is already a part of fundamental reality and so not explicable in other terms. And this move takes us straight back to the debate about consciousness between Śaṅkara and Rāmānuja. For them, the debate concerns the standing of individual subjects of consciousness (‘selves’, ātman) and not the attempt to explain phenomenality as such. For panpsychism posits that phenomenal consciousness is fundamental, and the goal is not to explain fundamental consciousness, but to use it to explain subject-level consciousness, or individual subjects of consciousness, or selves. The real hard problem of consciousness is asking why and how a self is intentionally and phenomenally conscious. In other words, if we take panpsychism as a solution to the hard problem, we must then enquire into the nature of subjects, the self.

Neither Śaṅkara nor Rāmānuja are physicalists, and their approaches are different

The only way that micropsychism and cosmopsychism can solve the hard problem of consciousness is by finding a mechanism that takes us from the fundamental to the non-fundamental. One must find a way to move from what is fundamental – micro-conscious entities or a universal consciousness – to ordinary subjects of consciousness. In doing so, one must provide answers to three pressing challenges – modal coherence, mechanical generation, and metaphysical explanation:

- Modal coherence: is combination from micro-conscious entities or decombination from a universal consciousness modally coherent? Does it avoid inconsistencies as to what is possible or impossible, and respect necessities and obligations as to the relationship between the entities?

- Mechanical generation: what is the mechanism for combination from micro-conscious entities or decombination from a universal consciousness?

- Metaphysical explanation: why does combination from micro-conscious entities or decombination from a universal consciousness occur?

The physicalist – one who holds that everything in the universe is physical – might respond to the second and third challenges with the promissory note of science: while scientists may not have the answers now, they will eventually. As for the first, they might point to how other physical properties combine, for example, gravitational or electromagnetic fields, even while the component parts of the system retain individual characteristics. While this may satisfy some, it won’t satisfy all. Neither Śaṅkara nor Rāmānuja are physicalists, and their approaches are different. Śaṅkara might respond to the challenges above as follows:

- The true self, ātman, is strictly identical with brahman. There is no incoherence between the true self and ultimate reality because they are the same.

- The empirical self as referred to earlier does not identify with the true self, ātman, in ordinary life because the empirical self is born with ignorance of its true nature as brahman. It can access this truth only through experience devoid of conceptualisation. Ignorance is the mechanism through which individual empirical selves are differentiated from each other.

- The ‘decombination’ of brahman into individual empirical selves occurs because of ignorance. However, Śaṅkara does not have an explanation as to why metaphysically there is ignorance that generates a failure to identify with the true self. His view is that this truth must be experienced in inwardness and not through rational explanation. Explanation has limits.

The other Indian schools provide other solutions to the three challenges. All, however, make the issue pivot on the nature of the human self, rather than on that of the phenomenal quality of individual conscious states. In this they seem to be ahead of their time. In grounding discussions of consciousness in a notion of ‘illumination’, they shift the problem away from the one that Chalmers introduces (and for which panpsychism seems to offer a promising solution) and onto the more fundamental ‘hard’ problem, which is to explain the nature of the self.

Given the ongoing and raging debates, it is perhaps safe to say that the knowledge that Naciketas, in the Kaṭha Upaniṣad, wanted more than anything else remains enigmatic. What we have tried to do in this essay is to demonstrate one way in which the traditions of ancient and classical India, encapsulating in their canonical texts the wisdom, insight and argumentation of seminal philosophers from the past, can fruitfully intersect with contemporary work being done around the world by modern philosophers in the more recent analytical tradition. One outcome of this exchange, we would like to hope, is that analytical philosophy itself becomes a truly global endeavour.