In every discipline that I’ve looked at, there is a striking generalisation that emerges, which I call the Law of Dynasties: in case after case, the movers and shakers of the fields had themselves been the students of an earlier mover and shaker. Aristotle was the student of Plato, Martin Heidegger was the student of Edmund Husserl, and Noam Chomsky was the student of Zellig Harris (the most brilliant linguist of his generation). To be sure, the Law of Dynasties results in part from self-selection. The very smartest (whatever that means!) of the rising generation are capable of identifying who the best teachers are, and the best teachers have enough smarts to know how to select the students with the greatest potential. Another sort of perfectly reasonable explanation for the Law of Dynasties is that if the teacher is one of the best of their generation, then their strong and positive support for a young scholar will be heard loud and clear in the profession.

These two explanations are part of the story, but there’s a lot more to it than that. I’ve been thinking about Franz Brentano, a German philosopher and psychologist whose career stretched from the 1870s up till the early years of the 20th century. I don’t know anyone whose intellectual descendants spanned such a broad range of ages, disciplines and influence – and, for that reason, he makes for an excellent test case of the Law of Dynasties.

Brentano’s impact was great in both psychology and philosophy. In philosophy today, the field is generally divided into analytic philosophy and continental philosophy, but both branches trace their particular perspectives back to the same man: Brentano. His work and his teachings also left marks on influential psychologists among his students, including Carl Stumpf (whom you might not know) and Sigmund Freud (whom you do).

The Law of Dynasties has another psychological basis, beyond the more rational two just mentioned. Highly charismatic teachers who arouse great devotion among their students also seem to pass on to them their tacit permission to be creative scholars. Such scholars feel they have been given licence to rethink the canon. While such a passage is devoutly wished for, it’s not an easy one, especially when the teacher retains their formidable charismatic force.

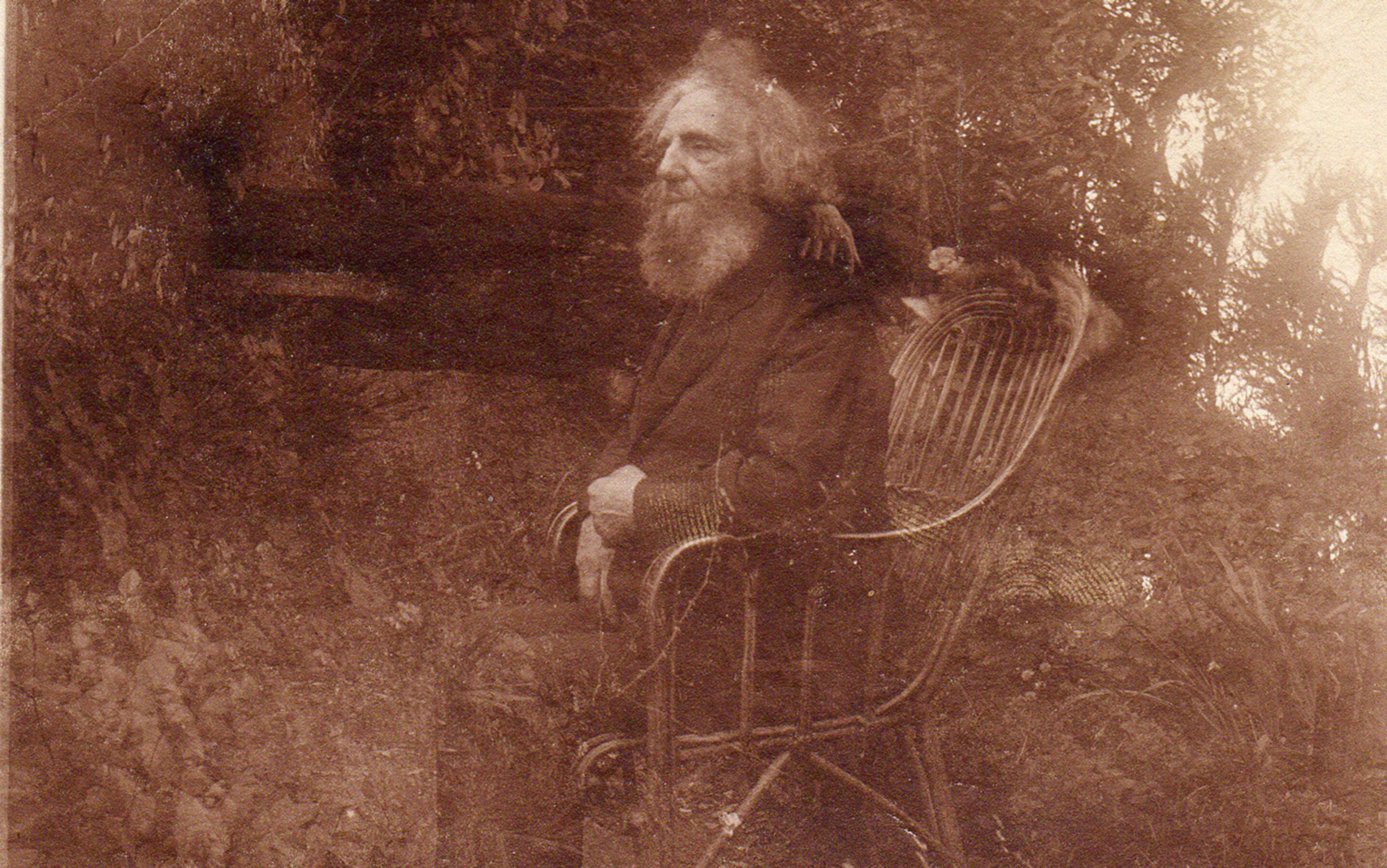

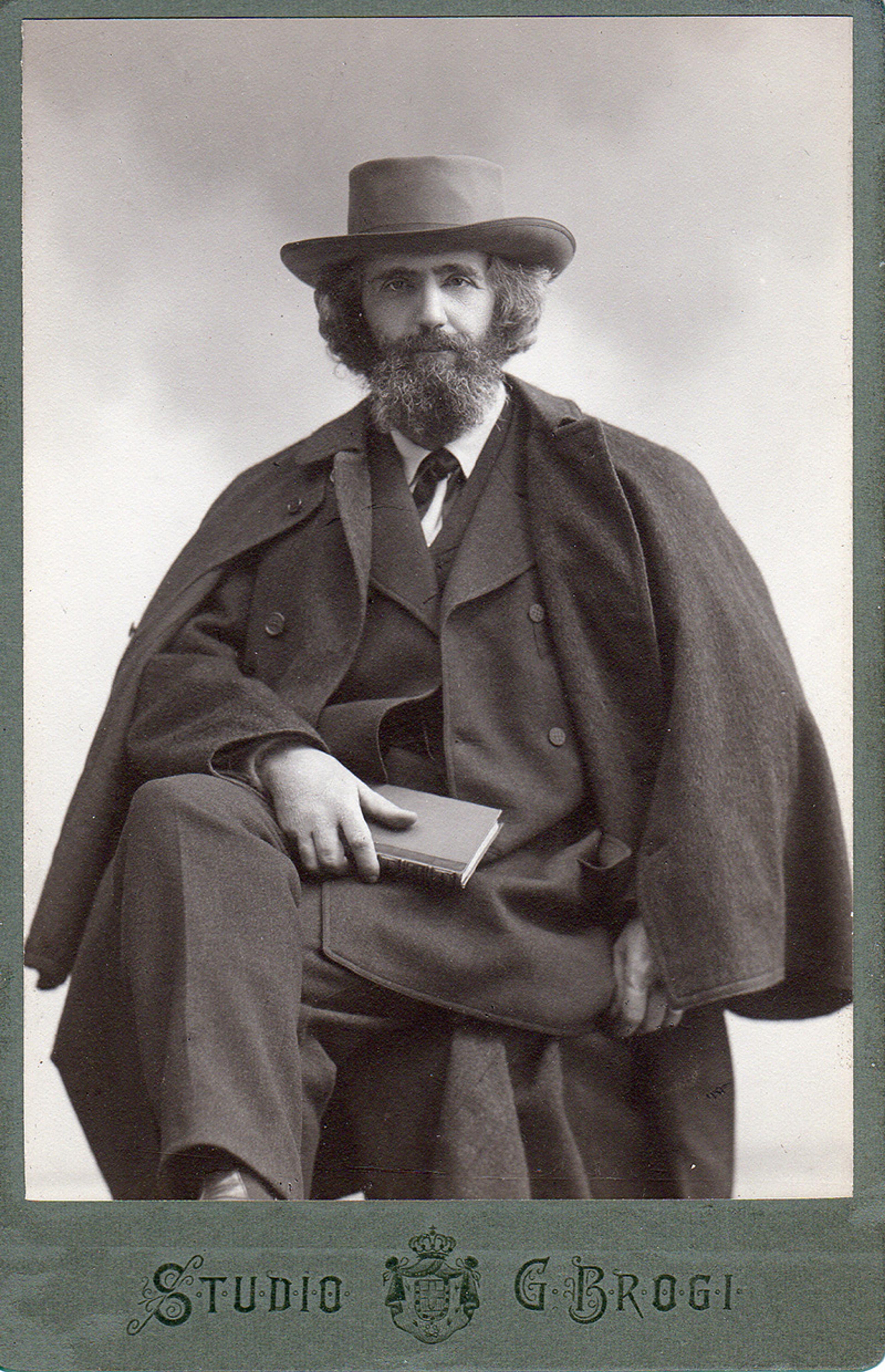

Brentano photoraphed in Florence in 1898. Courtesy the Brentano Archive.

Brentano was born in 1838 and grew up in Aschaffenburg, about 25 miles southeast of Frankfurt. He came from a cultured family of artists and intellectuals, most of them devout Roman Catholics. His younger brother Lujo became one of the most influential economists of his generation, and is also remembered for his stormy relationship with the German sociologist Max Weber.

At the age of 18, Franz Brentano went to Munich to study philosophy, and two years later went on to Berlin, where he studied Aristotle with one of the foremost philosophers of Germany, Friedrich Trendelenburg. In 1862, Brentano defended a dissertation on Aristotle at the University of Tübingen, and then did seminary work in Munich and Würzburg, taking vows and joining the priesthood in August 1864, when he was 26.

In 1866, he began teaching as a Privatdozent in Würzburg, and it was there that Brentano began attracting students. A Privatdozent in the German academic system was a faculty member whose remuneration came directly from the tuition paid by students who enrolled in his courses: no students, no pay, and no steady, reliable salary to fall back on. But students he had, and two of his first students would remain with him, and become famous themselves when they struck out on their own. Carl Stumpf, only 10 years younger than Brentano, would become a leader in German psychology, and Anton Marty became a philosopher at Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague, influential in the philosophy of language.

In 1869, at the time of the First Vatican Council, Brentano was asked to write a statement regarding papal infallibility, and he emerged after a period of study and reflection with arguments against it, a conclusion that set him on a path that led to his leaving the priesthood. The next summer, the Church in Rome established the principle of papal infallibility that sanctified whatever the Pope said when he was speaking ex cathedra. For the nascent empiricist that was Brentano, this was a bridge too far. Uncertain of his faith in this shifting world, he left the priesthood and his post at Würzburg in April 1873, even though he’d been promoted to professor just the year before. Soon after, he was offered the chair in philosophy at the University of Vienna, a fabulous position for a young man.

His decision to marry after leaving the Catholic priesthood meant a demotion from full professor

Brentano moved to Vienna in 1874, and in the years after he found many students who were eager to study with him, including Freud, Tomáš Masaryk (the future first president of Czechoslovakia) and the future philosophers Edmund Husserl, Alexius Meinong and Christian von Ehrenfels.

In 1880 and no longer a priest, Brentano proposed to Ida von Lieben, a woman he’d met from a distinguished Viennese family, but their love ran afoul of an Austrian law that forbade even a former priest from getting married. (Just deserts for leaving the Church in the Austro-Hungarian empire.) Brentano renounced his Austrian citizenship and became a citizen of Saxony, with the understanding that this political realignment would resolve the problem. It did not. The University in Vienna tried time and again to rehire him as a professor, but the Austrian government refused the nomination: he was forced to become once again a Privatdozent, and no efforts to overcome the conservative resolve of the Austrian government were ever successful. Being a Privatdozent made him uncertain of his income but, just as importantly, it meant that he was not authorised to advise students working on their doctorates, and had to send his advanced students to others who were full professors to finish their degrees.

Brentano’s marriage to von Lieben brought him into a more rarefied social circle in Vienna, whose members supported the arts and were politically active, sharing liberal views. He was 56 when Ida died suddenly in 1894, and he decided to leave Vienna the following year. For the next 20 years, he lived in Florence, where his former students would come to visit him from time to time. His degenerative eye disease became worse, and eventually Brentano lost all sight, making him dependent on others to read to him or take dictation. When war broke out in 1914 and Italy declared war on Germany and Austria, he moved to neutral Switzerland, and died in Zurich in 1917 at the age of 74.

For us today, Brentano is at times elusive. I daresay it is a stretch to fathom how his decision to marry after leaving the Catholic priesthood could have meant a demotion from full professor in Vienna to something just below what we would call an assistant professor today. But at other times we see him clearly, never more than through the eyes of his students who described a person of overwhelming charisma, with all the gifts that when rolled together create a teacher who attracted the best students and kept them in his thrall.

A word about what Brentano lectured on. He was part of a substantial wing in German and Austrian philosophy who believed that the new practice of experimental psychology was a game-changer for philosophy. He was by no means alone in this; the other major figure who shared this perspective was Wilhelm Wundt, widely viewed today as the father of experimental psychology. Brentano argued that there should be two quite different kinds of psychology, one that he called descriptive and one he called genetic (or empirical).

Unfortunately, the names don’t help us very much with how the two differ. Descriptive psychology was, at its heart, an account of what is directly perceived by the mind, and Brentano occasionally used the term phenomenology to refer to it. For him, phenomena are what the mind has direct access to, and it’s the task of the descriptive psychologist to understand the logical character of what the mind can think. On the other hand, genetic psychology is everything else, and pretty much corresponds to what psychologists study today. Genetic psychology is totally at home with the study of the anatomy and physiology of the brain and the sense organs of the human body, while descriptive psychology has no room for that at all.

The Vienna logical empiricists cited Brentano as one of their philosophical forebears in their manifesto of 1929

Here we see some of the origins of continental philosophy in the establishment and the defence of a study of the mind – descriptive psychology – that precedes any physical measurements (and has neither need nor time for physical measurements). Brentano’s student Husserl would make it his task to develop this, and for it he used the term phenomenology. We do know that Brentano maintained prayer and meditation as an important part of his daily life; he wrote passionately about that to his student Stumpf. Brentano’s writing about introspection made it clear that he recognised that some mental efforts at introspection were very hard indeed, a recognition that suggests his conclusions were based more on a systematic approach to introspection, one that grew not out of the needs of the psychology laboratory but rather of a rigorous internal awareness.

Analytic philosophy also saw Brentano as an important source. The logical positivists of the Vienna Circle who formed the hardest central core of analytic philosophy in the 1920s also saw Brentano’s work as leading to their position: Brentano placed himself on the side of learning through observation rather than with the philosophy of Immanuel Kant or G W F Hegel, and the Vienna logical empiricists cited Brentano as one of their philosophical forebears in their manifesto of 1929.

Brentano’s students testified to the power of his intellect and its effects on their own development. But he didn’t publish a great deal during his lifetime and, with the passing of his students by the end of the 1930s, awareness of his significance faded, though important studies of his work continue to this day.

My own interest in Brentano was piqued when I first read some of the things that his students wrote about him just after he died. I’ve known some charismatic teachers (and I will come back to one of them) but I’ve never seen such spot-on descriptions of what it’s like to try to keep one’s equilibrium in the warm glow that surrounds them – equilibrium both in an intellectual and a psychological sense. That warm glow can become bright and blinding at times.

This is how one of his students, Alois Höfler, described him:

Brentano was surrounded by a sort of romantic aura, the charm of a scion of the Brentano dynasty of poets and thinkers. His flowing black locks, his thick black beard, and his pallid face were enigmatic in their effect, with the silvery flecks of grey among the black … the strange quality of Brentano’s face, which could only be that of a philosopher, a poet or an artist, sprang from his coal-black eyes which, always lightly veiled, bore an entirely distinctive expression of weariness.

Stumpf was Brentano’s first student, and he wrote:

[I] had never met an academic, neither in my student days nor since I have been a professor, who dedicated himself to such an extent, both verbally and in writing, to his task as a teacher … the friendly relations with his students, based upon an equally absolute devotion to the highest purposes, was one of the strongest needs of his life.

Stumpf left a huge mark on psychology, a field that was just getting off the ground when he entered it. After holding professorships in Würzburg, Prague and Halle, he was called (as they put it in those days) to become professor in Berlin, and it was there that he created an institute that would become the centre of work on gestalt psychology after the First World War.

He wrote about ‘a certain touchiness on Brentano’s part toward dissension that he thought to be unfounded’

After Brentano’s death, when Stumpf himself was 70 years old, he set to paper some of his recollections of Brentano:

I wish to express the love and gratitude which I owe to my great teacher which I will retain until the day I die. The close relationships he established with his students and which he was so eager to maintain played a more important part in his inner life than is the case with many other thinkers.

Stumpf spoke of the metamorphosis that Brentano produced in him: he’d started at the university expecting to study law, but after some weeks that resolution weakened:

Before Christmas I sought him out to inform him of my intention of choosing philosophy and theology as my life’s work. I even wanted to follow him into the priesthood, so much of an example had he set for me.

From that day on, Brentano spent many hours walking and talking with Stumpf. As Stumpf’s own professional stature grew, and the two no longer lived in the same city, they naturally grew apart intellectually. Stumpf bore some of the burden of having been Brentano’s first student; he wrote about ‘a certain touchiness on Brentano’s part toward dissension that he thought to be unfounded’. If Brentano

encountered basic intuitions in his students’ publications which were considerably different from his own, and which were not thoroughly justified and defended on the spot, he was inclined to consider them at first as unmotivated, arbitrary statements even though they may have been subject to several years’ thorough study or may have matured imperceptibly without one’s having been expressly aware of it. Occasional ill-feelings were unavoidable in the face of this.

We find this pattern over and over again among the great charismatic teachers whose students became prominent in the next generation: they can’t accept the notion that their students might go off to disagree with them.

Freud’s professional career didn’t engage with the kinds of psychology that Brentano was involved in, but he took five philosophy courses from Brentano during the years of his studies – the only courses outside of medicine that he took. He wrote to a friend, Eduard Silberstein:

One of the courses – lo and behold – just listen, you will be surprised – deals with the existence of God, and Professor Brentano, who lectures on it, is a marvellous person. Scientist and philosopher though he is, he deems it necessary to support with his expositions this airy existence of a divinity … This peculiar, and in many respects ideal man, a believer in God, a teleologist, a Darwinist and altogether a darned clever fellow, a genius in fact. For the moment I will say only this: that under Brentano’s influence I have decided to take my PhD in philosophy and zoology.

Years later, in 1932, Freud recalled a translation from English that he’d done during his student days, and he explained that his name had been suggested as a translator by Brentano, ‘whose student I then was or had been at a still earlier time’.

Christian von Ehrenfels was an aristocratic Austrian who studied with Brentano in Vienna, and then later with his former student Alexius Meinong. After 1896, Ehrenfels was professor of philosophy at Charles University, the German university of Prague.

In his later years, Ehrenfels wrote about his two teachers, Brentano and Meinong, with insight:

So let me confess right away that I regard Brentano as the greater of the two as regards productive capacity. For keenness of intellect they were perhaps evenly balanced. But Brentano was, in my opinion, by far the more fortunately endowed scholar. He had an immediate instinct for that which was clear and essential and also for the admissibility, where appropriate, of abbreviated methods of thinking, whereas Meinong’s mind seemed to be directly attracted to that which is intricate, minute and laborious. My impression was that Brentano also excelled more as regards economy of effort and the methodical influence exercised by the style of his verbal and written presentation. What we need is the brevity of clarity and not the prolixity of superfluous assurances … I must here stress that I was brought most impressively into contact with that living quality which can best be described as scientific conscience or scholarly morality not by Brentano but by Meinong. And yet all the conditions ought to have been here more favourable for Brentano. Brentano was from the beginning for me the more imposing intellectual personality; he was by far the elder and more distinguished of the two (and in those days, as a lad coming up to Vienna from my native Waldviertel and the small town of Krems an der Donau, I still laid some store by outward distinction). Brentano held tutorials lasting several hours, and a private recommendation soon brought me into personal contact with him. Brentano was a charming interlocutor and an attractive figure in speech and appearance.

Ehrenfels’s most famous work was Über Gestaltqualitäten (1890), or On Gestalt Qualities, in which he developed the major Brentanian theme of the logical relationship of parts and wholes, as well as the idea of a shape, or gestalt. Ernst Mach, an older scientist-philosopher, had talked about a gestalt as the thing that is important but not the sensory perception itself. The clearest example of a gestalt is a melody: it’s composed of notes, but it’s the totality of how the notes are put together, with order and rhythm, that makes a melody what it is. Ehrenfels came back to that, with a nod to Mach, and made the study of these gestalts the centrepiece of his paper, ultimately one of the most influential papers in the entire history of psychology. Now, we often say in casual speech that the whole is not the sum of its parts, but the task was to say exactly what the difference was between the whole and the collection of its parts. Ehrenfels took a musical melody as the perfect example of a whole that’s so much more than its parts (though the same thing could be said for a word or a sentence). A melody is easily recognised as the same even if it is raised or lowered by a musical interval. What is it then that’s the melody, if all of the component notes have changed? It is something relational that ties the parts together.

‘I do not feel humiliated at all in this role of a pupil … Brentano only wants to give, and not to receive’

Right from the first paragraph, Ehrenfels’s article begins with the recognition that the starting point of his work lay in Mach’s Analysis of Sensation (1886). Ehrenfels wrote to a friend: ‘I sent Mach “Gestalt Qualities” and he replied in a friendly manner that he had already given the main thoughts in 1865, and had expressed them in a more psychological way.’ This seems like an unusually gracious recognition of intellectual continuity on Ehrenfels’s part, but it also seems that it was, alas, dismissed by Mach with a toss of a hand.

Ehrenfels in turn was the first teacher of Max Wertheimer, who would go on to be a graduate student in Berlin under Stumpf, and then in Würzburg under Oswald Külpe, where he finished his degree. Wertheimer would later develop gestalt psychology, which would succeed better than any preceding school of psychology in making explicit the active principles that dynamically organise the perceived world. Ehrenfels provided an important step forward in emphasising the logical gap between the perception of the parts and the perception of the whole, which can subjectively be far more important than the parts.

Years after he was his student, Ehrenfels sent Brentano a letter that contains some language in which Ehrenfels refers to Brentano in the third person. Perhaps this prose is a quotation from something he wrote during his student years. It is certainly frank:

Especially with respect to our relationship I then developed the following directives: Brentano is an extremely intellectually productive personality who unfortunately, like most brilliant people, suffers from a characteristic concomitant disadvantage: from one-sidedness and biasedness which is a part of his particular, eminently developed character. Trying to convince him of some kind of result in a certain field of science or of even a general cultural field which was disagreeable to his nature, would turn out to be a completely futile effort which would lead me to becoming emotional and to falling out with my admired and highly deserving teacher to whom I am deeply indebted. So from then on I was much more determined to adopt the behaviour of the pupil towards the teacher in my future conduct to Brentano (a style familiar to me anyway) and to accept gratefully all good and worthy things that he still would give me. But when dealing with him I consciously intend to exclude all intellectual and emotional reactions which to my sense of delicacy cannot be assimilated by him – and I shall not be affected by his underestimation of what I appreciate … or by his scornful and derisive treatment of what is for me great and praiseworthy … If he were an ordinary person, such behaviour would altogether be too arduous and perhaps incompatible with self-esteem. But concerning Brentano, I do not feel humiliated at all in this role of a pupil … Brentano only wants to give, and not to receive. To him producing and sowing the seeds of thought is vital to the zest for life. In case somebody wants to reciprocate by adopting his manner, he will be silenced immediately by Brentano’s superior dialectics and will be laughed at secretly (and sometimes publicly).

For Ehrenfels as for all of Brentano’s other students, the powerful draw of their teacher’s intellectual passion and his unwavering certainty was a great source from which came their own opportunities to find new ways to understand the mind. The cost of the students’ independence was great, but it was worth it.

The philosopher best remembered today among Brentano’s students is Husserl. Anyone who wants to study phenomenology – and that includes most students of continental philosophy – has to begin their reading with him. Just like Stumpf, Husserl hadn’t planned to be a philosopher. His intention had been to be a mathematician, and in fact he earned a PhD in mathematics after studying with Leopold Kronecker and Karl Weierstrass, two of the leading mathematicians of the day. But it was Brentano’s lectures that captured his imagination. To be able to teach at the university level, he needed a habilitation thesis, and for this he needed to work with a professor (which Brentano no longer was), so he went to study with Stumpf, writing a dissertation on the philosophy of mathematics in 1887.

From where we stand today, Husserl is vastly better known than Brentano. He is remembered as the philosopher who created phenomenology, the study of immediate experience, even if this grew directly out of Brentano’s descriptive psychology. But if we listen to how Husserl thought about his teacher after Brentano’s passing, we hear about the emotional struggle that Brentano’s students had if they wanted to move his programme in a new direction.

Husserl spoke with some emotion of how he saw Brentano when he listened to his lectures:

in every feature, in every movement, in his soulful, introspective eyes, filled with determination, in his whole manner, was expressed the consciousness of a great mission.

Is there a better description of charisma? And at the same time, Husserl recalled Brentano’s language as

the language of dispassionate scientific discourse, though it did have a certain elevated and artistic style through which Brentano could express himself in a completely appropriate and natural way.

Brentano left an impression: ‘he stood before his young students like a seer of eternal truths and the prophet of an otherworldly realm.’ Even after Brentano’s death, Husserl recalled the force of attraction to his former teacher, writing:

In spite of all my prejudices, I could not resist the power of his personality for long. I was soon fascinated and then overcome by the unique clarity and dialectical acuity of his explanations.

Brentano was, Husserl noted, convinced of the truth of his own philosophy:

In fact, his self-confidence was complete. The inner certainty that he was moving in the right direction and was founding a purely scientific philosophy never wavered …

and developing his philosophy was

something he felt himself called to do, both from within and from above. I would like to call this absolutely doubt-free conviction of his mission the ultimate fact of his life. Without it one cannot understand nor rightly judge Brentano’s personality.

Still, Brentano was ‘very touchy about any deviation from his firmly held convictions’; he became

excited when he encountered criticisms of them, adhered rather rigidly to the already well defined formulations and aporetic proofs, and held out victoriously, thanks to his masterly dialectic, which, however, could leave the objector dissatisfied if he had based his argument on opposing original intuitions.

And, Husserl added, ‘no-one took it harder when his own firmly entrenched convictions were attacked.’

Thus, the connections that form tight bonds, both personal and intellectual, at the beginning of a student’s career evolve into forces that lend themselves to rupture. Husserl, again, explained straightforwardly how this happened in his relationship with his teacher:

At the beginning I was his enthusiastic pupil, and I never ceased to have the highest regard for him as a teacher; still, it was not to be that I should remain a member of his school.

Husserl knew that he was going to move on and become an independent thinker:

I knew, however, how much it agitated him when people went their own way, even if they used his ideas as a starting point.

Even if? Surely Husserl knew perfectly well that that was the worst possible case, from Brentano’s point of view. Be my student and then disagree with me?

He could often be unjust in such situations; this is what happened to me, and it was painful.

When I read Husserl’s words about his relationship with his teacher, I must admit that I find myself silently urging him to show more forbearance in his thoughts about Brentano, since, after all, it’s Husserl who would be far more famous a century later. But Husserl had no way of knowing that. Like all of us, he was swimming in uncertain waters, never sure if the current was about to wash him out to sea. And he knew that he couldn’t provide an argument for his point of view that Brentano would find persuasive. Husserl could give in to his teacher’s criticisms, or he could set out on his own, even while he knew that Brentano had better arguments than he did, for the moment. He was obviously talking about himself when he wrote:

the person who is driven from within by unclarified and yet overpowering motives of thought, or who seeks to give expression to intuitions which are as yet conceptually incomprehensible and do not conform to the received theories, is not inclined to reveal his thoughts to someone who is convinced that his theories are right – and certainly not to a master logician like Brentano.

We are left to conclude that Husserl tried early on but failed to engage Brentano in a conversation in which Husserl’s ideas were something other than a heresy. He wasn’t able to meet his teacher’s standards for logical persuasion. ‘One’s own lack of clarity is painful enough,’ Husserl went on. But he could neither convince Brentano that something was wrong in his teachings, nor persuade him that Husserl’s alternatives made sense: ‘One finds oneself in the unfortunate position of neither being able to produce clear refutations nor being able to set forth anything sufficiently clear and definite.’ An unfortunate position, indeed: to be struck dumb in the presence of one’s teacher.

My development was like that and this was the reason for a certain remoteness, although not a personal estrangement, from my teacher, which made close intellectual contact so difficult later on. Never, I must freely admit, was this his fault. He repeatedly made efforts to re-establish scientific relations. He must have felt that my great respect for him had never lessened during these decades. On the contrary, it has only increased.

But then many years went by with each man going his own way. Towards the end of Brentano’s life, while he was living in Florence, Husserl went to visit him there. Almost blind at that point, Brentano was unable to read and able to write only if someone took dictation. His hair had turned grey, and his eyes had lost the gleam that once captivated his students. Husserl could see that his former teacher was chafing under the conditions he had to live in, with rarely a colleague to speak to about philosophy. Husserl could listen, though:

Once more I felt like a shy beginner before this towering, powerful intellect. I preferred to listen rather than speak myself. And how great, how beautifully and firmly articulate, was the speech that poured out.

Once, however, he himself wanted to listen, and without ever interrupting me with objections, he let me speak about the significance of the phenomenological method of investigation and my old fight against psychologism. We did not reach any agreement.

And perhaps some of the fault lies with me. I was handicapped by the inner conviction that he, having become firmly entrenched in his way of looking at things, and having established a firm system of concepts and arguments, was no longer flexible enough to be able to understand the necessity of the changes in his basic intuitions which had been so compelling to me.

Husserl never lost his love for Brentano the teacher. In that final meeting, he found that Brentano had ‘a slight aura of transfiguration, as though he no longer belonged entirely to this world and as though he already half lived in that higher world he believed in so firmly.’ The world would soon lose a brilliant thinker and teacher. Husserl ended his note with these words: ‘This is how he lives on in my memory – as a figure from a higher world.’

Fast-forward to 2011. The linguistics department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which had been established by Chomsky and Morris Halle in 1961, organised a gala affair for all the students who had earned their PhDs in the 50 years since the department, the one that launched generative grammar, opened its doors. I was there. On the first night, there was a dinner for students – which is to say, former students, though we were virtually all professors of linguistics somewhere, and there were about 200 of us, all told. When the dining was over, people stood up to share recollections of our teachers in the years we’d spent at MIT studying linguistics with Chomsky, Halle and their colleagues.

It was not long after that dinner that I read what Stumpf and Husserl wrote about their memories of Brentano, and was struck by how similar the language and the feelings were to what Chomsky’s students remembered. What Husserl wrote about Brentano, that ‘towering, powerful intellect’ against whom one’s arguments seemed feeble and ill thought-out: that was what people remembered from their meetings with Chomsky. Their brains (or was it their minds?) seemed to stop functioning the moment they walked into his office. Just as Stumpf said about Brentano, it seemed that Chomsky’s confidence ‘held out victoriously, thanks to his masterly dialectic, which, however, could leave the objector dissatisfied if he had based his argument on opposing original intuitions.’ When Brentano’s students followed his direction, all was well, but when they decided to take a tack different from Brentano’s, it was necessary to acknowledge that they were no longer convinced of the intellectual position that he had developed. With Chomsky as with Brentano, this put the student in a very challenging, very difficult position.

The psychodynamics of the relationship between a teacher and a student are complex. There is today, I daresay, a tendency all too quickly to interpret them in terms of power and in some cases sexuality. The conversations on which we have eavesdropped among Brentano’s students shed light on the powerful emotions that the teacher generated in the hearts of his students, and while they spoke of the difficulty they had in breaking away from him, what we have to learn from these remarks is that Brentano was extraordinarily successful in finding a way to fire up his students to becoming their own selves. That is, they all report that Brentano was hard to break away from – and yet they were able to do exactly that. I am convinced that Brentano succeeded brilliantly in the deepest and most difficult task of a research advisor: he convinced his students that they were worthy of finding their own intellectual voices and to strike out on their own.

This, I think, is an important part of the Law of Dynasties. When a teacher succeeds, they transmit to their students the freedom to go their own way. A part of this surely comes from the teacher’s own life, as the students see it, and Brentano’s life was lived, as his students could see with their own eyes, with a selfless devotion to the ideas he cared about and lectured on. What I would give to be able to go back 125 years and sit in Brentano’s lecture for an afternoon.

This essay is adapted from ‘Battle in the Mind Fields’ (2019), coauthored by John A Goldsmith and Bernard Laks.