In Vienna, in late February 1895, a 30-year-old woman, Emma Eckstein, is about to undergo an operation. She has recently complained of a few health problems – mostly stomach pain and discomfort, some sadness, especially around her period. Luckily, a young Berlin doctor by the name of Wilhelm Fliess is there to help. He comes highly recommended by a long-time trusted family friend, himself a reputable physician, Sigmund Freud. They agree that Eckstein’s menstrual stomach issues can be addressed through a simple surgery on an altogether different body part – Fliess removes a bit of bone from inside her nose.

The late 19th century saw a flowering of interest in the nasogenital reflex – the idea that there is a strong physiological link between the nose and the genitals. The nasogenital concept could allegedly explain all manner of trouble, not just in the reproductive system but across the board. The nose provided a clinical shortcut of sorts, a kind of map of the body. For mild illness, treatment could involve stimulating the problem areas of the nasal mucosa with cocaine. If the situation was a bit more serious, it may further be necessary to cauterise – with acid or electricity – the implicated ‘genital spots’ in the nose. In the most stubborn cases, however, the only course of action left to the well-meaning healer was to surgically cut out sections of the inferior turbinate bone. Also known as nasal conchae, these are thin shell-shaped structures crucial for warming, humidifying and filtering air – nothing to sneeze at.

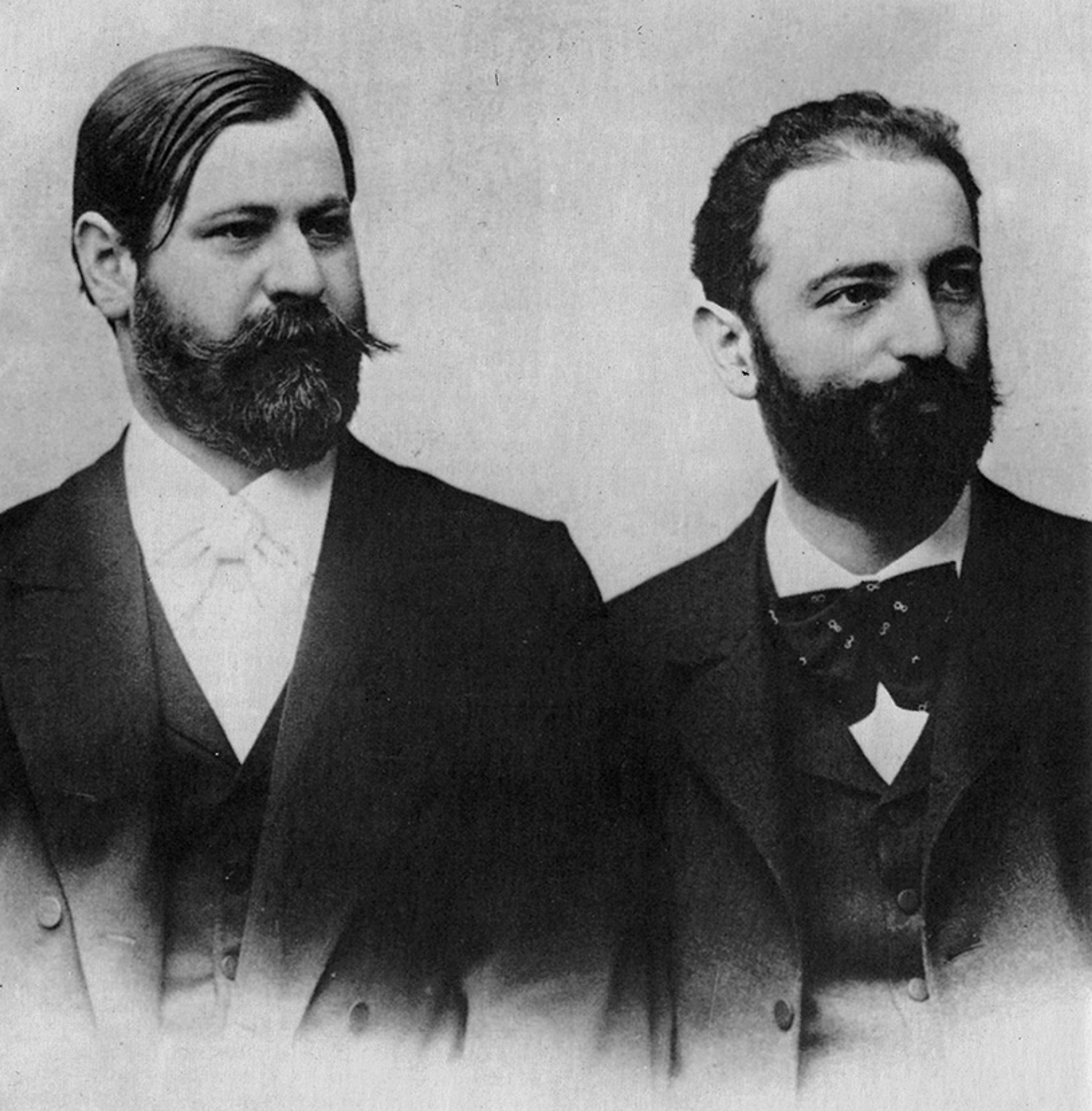

The nasogenital reflex strikes most people today as a wacky brainchild of an obvious charlatan – the so-called nose-and-throat specialist Wilhelm Fliess. The famously no-nonsense science writer Martin Gardner christened him as ‘one of the giants of German crackpottery’. Recent scholarly literature on Fliess revolves around his close relationship with and profound influence on Freud. In retrospect, some try to minimise the affinity between them, whereas others use it to stain the reputation of Freud who had, after all, dubbed Fliess ‘the Kepler of biology’. While at the University of Vienna, Freud lectured on Fliess’s ‘enthralling material’, as he called it. In some of the nearly 300 letters he wrote to Fliess, they discussed co-authoring a book to review the two men’s breakthroughs – weaving together anxiety and nasal reflex neuroses. Freud very much hoped the phenomenon would be termed ‘Fliess’s disease’ to honour his friend’s discovery. In the meantime, he intended to name one of his two youngest children after Fliess. ‘Fortunately,’ a biographer of Freud’s remarked, ‘they were both girls.’

Sigmund Freud and Wilhelm Fliess in the early 1890s. Courtesy Wikipedia

Freud’s admiration was not just professional – it took on a more embodied form, too. He had his own nasal mucosa treated by Fliess plenty of times, although it seems to have gone better for him than it did for Eckstein. Following her 1895 operation, she racked up some new health complaints – nose pain, stinky pus, excessive bleeding. Two weeks later, her state had deteriorated only further, and so, a worried Freud called upon a local surgeon to investigate. The surgeon promptly came upon half a metre of gauze that Fliess had left inside the nose in question – ‘a flood of blood’ was the result, Freud wrote to Fliess. At risk of fainting, Freud hurried out of the room to be soothed by a glass of cognac. ‘So this is the strong sex,’ Eckstein commented, bleeding, her face disfigured. One may think this sort of thing would put an end to anything Fliess, nasogenital or otherwise – a neat narrative ribbon to wrap up the story of an incompetent quack.

To modern ears, the nasogenital reflex theory sounds ridiculous and it has indeed been discredited. In the rearview mirror of history, it is rather easy to sort past figures – this one ‘prescient’, that one ‘blinkered’. We generally expect there would be signs to make the call through the window, too – not neon lights necessarily, but clear enough. And yet, the bungled procedure did little to alter Fliess’s contemporaries’ assessment of the man. The Freud-Fliess bond did eventually dissolve, but the episode of the Eckstein nose was not to blame. In Freud’s estimation, Fliess ‘did it as well as one can do it’ – the gauze mishap was ‘one of those accidents that happen to the most fortunate and circumspect of surgeons.’ Instead, despite (or perhaps because of) a tinge of, in Freud’s words, ‘unruly homosexual feeling’ between the two, their passionate friendship cooled years later under accusations of plagiarism. In particular, Fliess was irked by the lack of proper credit from Freud for his groundbreaking idea that everyone was inherently bisexual. More remarkably, in spite of it all, Eckstein herself did not seem to harbour much ill feeling towards the duo – she went on to become a psychoanalyst. Even Fliess’s general ‘reputation as a miracle worker remained intact,’ another of Freud’s commentators observed.

The nose incident failed to stamp out people’s enthusiasm for matters nasogenital. Perhaps this was because the nasogenital phenomenon was not so much a quirk of Fliess’s psyche as an instance of pretty reasonable, in some ways even forward-looking clinical judgment of late-19th-century science. After all, ‘Nasal-reflex therapy was … widely embraced in the practice of medicine at the turn of the century,’ according to the historian Edward Shorter’s From Paralysis to Fatigue (1992). At the time, even Fliess’s critics were often impressed by the empirical findings he presented. Rather, it was his concept of ‘nasal reflex neuroses’ and especially the suggested prevalence that elicited disagreement. To its fin-de-siècle contemporaries, the nasogenital hypothesis would have looked entirely sensible, or at least worth investigating further. And investigate further they did – nasogenital theory stuck around until the mid-20th century.

This reflex theory was taken to mean that distant organs could affect each other – for better or for worse

Several considerations may give us a sense why the nasogenital idea was compelling even to the well-informed minds of the period. Fliess himself struck his peers as ‘a man of highly impressive personality and intellect’, ‘well read in virtually the entire field of medicine’ and in possession of ‘a comprehensive and imaginative grasp of current biological knowledge’. His nasogenital conception also built on an old idea. One of the earliest mentions of a connection between the nose and the genitals is attributed to Sushruta, a pioneering physician of the 6th century BCE from what is now northern India. Hailed as ‘the father of plastic surgery’, he was proficient at using skin grafts to reconstruct noses and such – cutting off bits of the face was a common punishment at the time. Later nasogenital cameos can be found in texts by Hippocrates – anointed ‘the father of medicine’ – and his follower Galen, whose moniker is still a work in progress. The set of observations the ancients relied on was not all that different from what inspired our nasogenital theorists around 17 centuries later.

Some of the excitement about all things nasogenital could be explained by contemporary trends in science. The hypothesis came on the scene during the reign of so-called ‘reflex theory’ – one of the dominant medical models between 1850 and 1900. According to this view, nervous pathways were responsible for the running of bodily organs – a feat enabled by the connectivity highway, the spine. Moreover, action could often bypass conscious control. To anyone keeping up with the latest empirical developments, experimental work uncovering various automatic reflex arcs via the spinal column was electrifying. The classic knee-jerk reflex at a tap of a tendon was described in 1875.

It must have seemed like reflex arcs were turning up all over the place, commanding not only muscles but also internal organs, and who knows what else. In the minds of many, this likely gave some substance to an ancient but vague idea of ‘sympathy’ between organs. Suddenly, there was a concrete physiological mechanism on offer – it was not mere ‘sympathy’, it was reflex action. This reflex theory was taken to mean that distant organs could affect each other – for better or for worse. Some theorists preferred to elevate the impact of the reproductive system on the brain – fitting our image of the Victorians. Others focused on the mutual influence between the stomach and the brain – a sort of prequel to our current fascination with the gut-brain axis. Meanwhile, Fliess and colleagues landed on the nose – and its counterpart down below.

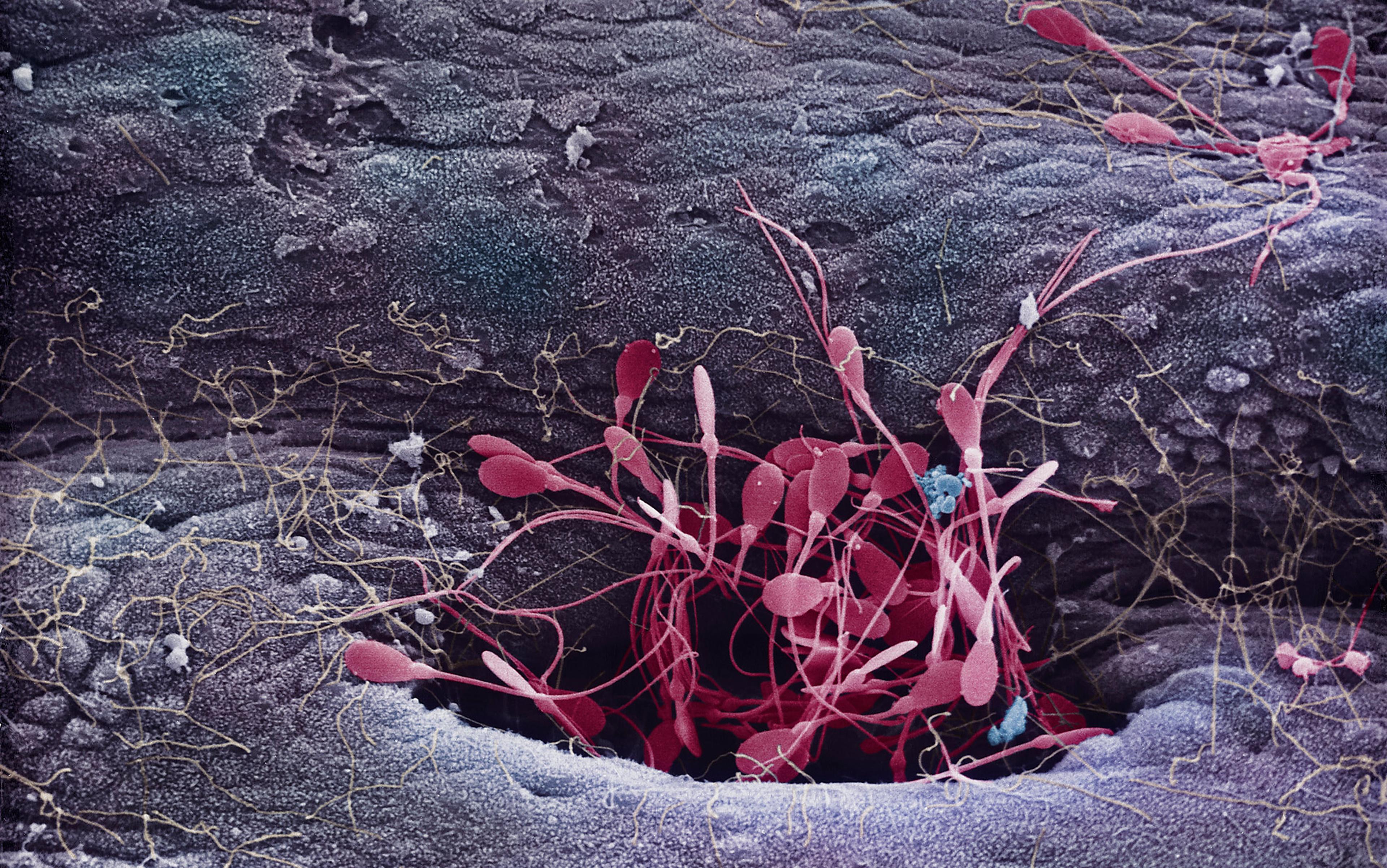

The choice was less random than it might at first seem. The nose is home to erectile tissue that becomes engorged due to increased blood flow. The only other location where this happens is – notably – the genitals. For example, nasal tissue tends to swell during sexual arousal, so much so that we have a term for the phenomenon – ‘honeymoon rhinitis’. In some people, this leads to a stuffy, runny nose, or uncontrollable sneezing during sexual congress. At times, though, even a racy fantasy might be enough to set it off. Meeting a London man with a case of honeymoon rhinitis is what stimulated the nasogenital interest of John Noland Mackenzie, an eminent American physician. Having first encountered the man in 1879, he dug into the subject and published his initial results under the heading ‘Irritation of the Sexual Apparatus as an Etiological Factor in the Production of Nasal Disease’ (1884). Now, crucially, this was before Fliess’s independent conjectures on the subject. If this were a history of some celebrated scientific theory, we would be compelled to campaign for Mackenzie to be crowned as the rightful discoverer of the nasogenital connection. As it is, perhaps Freud would feel gratified he got his wish to have his former friend Fliess so immortalised.

Continuing with the evidence, in women, nasal mucosa seemed to become erect during menses. Some reported experiencing monthly vicarious nosebleeds, and not only during menstruation but pregnancy, too. Nosebleeds were likewise common in boys going through puberty, ‘upon the full development of their sexual powers’, as Mackenzie noted. Today, we attribute any such occurrences to hormonal changes. Back then, the thought was that overexcitement of one set of organs might lead to trouble in the other, and so the nose could serve as a dead giveaway for a variety of bodily happenings, including masturbation, coitus interruptus, or a lifestyle of sexual excess. Consider one of Mackenzie’s patients from 1889 – a 23-year-old woman suffering from asthmatic ‘stoppage of the nostrils’. Since the esteemed physician could find nothing out of order, ‘Reluctantly she confessed that every night for five years she and her husband had indulged in intemperate venery.’ No decent nose could take that. Luckily, following doctor’s orders, ‘[m]oderation in their sexual relations’ solved the problem and, at the time of the report, her nose had not relapsed for nine years.

The nasogenital bond seemed to fit with contemporary evolutionary thinking. Charles Darwin published his theories of natural and sexual selection in the 1850s and 1870s. Nasogenital theorists noted that the sense of smell plays a key role in arousal and reproduction in the animal kingdom – they surmised there must be a phylogenetic link between the organs involved. Indeed, research on the effects of so-called pheromones continues today, both in humans and nonhuman animals. Of relevance to the nasogenital reasoning of an evolutionary variety, experimentalists in 1912 cut out Fliess’s genital spots from the noses of young rabbits, who, as a result, failed to fully develop their genitalia – surely a smoking gun. Numerous similar studies followed, on more young rabbits, but also guinea pigs, mice, rats, dogs, monkeys, among other critters. A literature review in an otolaryngology journal published by the American Medical Association still discussed these experiments in 1945 – and favourably.

Fliess had seemed to demonstrate it was only his specific genital zones, plus cocaine, that would help

Ultimately, the crux of the theory was a two-way nasal-genital dependency in sickness and in health. Nowadays, the gold standard of clinical evidence is the randomised placebo-controlled trial, though even this method – our best – is far from foolproof. Before this practice became the norm in the mid-20th century, people would rely on a variety of suggestive but ambiguous clues. If many patients seemed to get better after treatment, that could be taken as support for the hypothesis – especially in light of the broader theoretical considerations. Perhaps surprisingly, get better they did. In 1903, an American doctor wrote that, despite initial scepticism, the nasogenital cure ‘made friends out of scoffers, and many a man who began to experiment with it in the hope of discrediting it and exposing its fallacy wound up as a disciple and an apostle. Wherever the method was subjected to impartial tests it has achieved an amazing number of successes.’ In 1914, Fliess himself summed up the state-of-the-art by noting a 75 per cent success rate of his clinical approach across more than 300 separate scientific publications.

Here is a typical example:

Case 2 – AK, aged 25, single; Oct 5, 1910. Menstruation was always painful; on the first two days the patient was compelled to go to bed and take full doses of codein [sic]. Two large enchondroses of the septum were removed, and the galvanocautery was applied to sensitive spots. Three years later the patient reports that she has never had menstrual pain since.

AK’s vignette appeared in a 1914 paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association. It was a report on the nasogenital treatment outcomes of 93 women in New York. The author – ‘a distinguished laryngologist’ – was aware of the most likely methodological critiques at the time. In response to concerns that the improvement was simply drug euphoria, he pointed out that the patients actually ‘received but little cocain [sic] and none at all at the time when their sufferings were due’. Notably for our nasogenital practitioners, Fliess had previously seemed to demonstrate it was only his specific genital zones, plus cocaine, that would help. If it was the general narcotic effect of the substance, any old nasal area should do. To neutralise the placebo charge, the author insisted that ‘the greatest care was taken to eliminate the possibility of suggestion’, in that ‘no promises were ever made. On the contrary, it was briefly explained that some had been benefited and it was hoped that they also might obtain relief’ – a failsafe anti-placebo manoeuvre, then.

And so, a range of empirical data, including animal studies, appeared to lend credence to the hypothesis. As it happens, some funky-sounding 19th-century nasal insights have stood the test of time. As reported by a German physician in 1895, the two air passages do take turns to lead the whole breathing business – one congesting, just as the other decongests. A single ‘nasal cycle’ can last anywhere from half an hour to six hours in different individuals, set by their autonomic nervous system. In addition to the experimental findings, the clinical pitch of the nasogenital reflex could have struck people as pretty moderate, among the late-1800s picks. Proponents of nasogenital procedures would say as much themselves – particularly in comparison with some of the wild practices of contemporary gynaecologists. According to the New York laryngologist, the patients’ ‘relief without drugs, operation and uterine treatment by a few applications to the nose adds materially to their comfort and the joy of living.’

More generally, the tone of much of the writing on the subject feels less like fishy quackery and more like measured excitement at the promise of a new area of interdisciplinary scientific enquiry. In 1897, for instance, Mackenzie spoke at length about the physiological link between the nose and the genitals at a meeting of the British Medical Association in Montreal, Canada. In his remarks, he railed against the quacks, charlatans and imposters of earlier eras who thought that astrology underpinned nasogenital phenomena. In contrast, as Mackenzie aimed to show, the turn-of-the-century ‘study of the relations between the nose and the sexual apparatus opens up a new field of research, of pleasing landscape and almost boundless horizon, which bids to its exploration not only the physiologist and pathologist, but also the biologist.’ At the centre of it all lay ‘an interesting enigma, whose significance it will be the task of the future to divine’. But the future has arrived, and it is not impressed.

One obvious lesson from all this is that, rather plausibly, we today have some convictions and conceits that educated people of the future will label as crackpottery. Plenty of fierce debates are raging as we speak. Take the psychologist Irving Kirsch’s ongoing battle to challenge our widespread acceptance of antidepressants. He has argued that whatever potency they show is due to the placebo effect, hence the moniker ‘the emperor’s new drugs’. Backlash from the medical community has been fast and furious. It is an open question as to how our descendants will appraise the situation. Kirsch could drop off the map or he could turn into a maverick who had managed to shed the doctrine of his time and see the light. I am of today’s intellectual community myself and so quite unable to make any firm predictions. So long as the hypotheses meet our current evidential expectations, I do not think we can fully know either way.

This does not deny that we can comfortably rule out a great deal of empirically suspect or simply under-evidenced theories. We test and retest, and test some more, moving onwards and upwards in step with the scientific method – as we must. Happily, our standards and methods have improved dramatically over time. But likewise, if all goes well, our methodological prowess should continue to grow in the longer term. It is conceivable that a century or so in the future could be even more foreign to us – methods-wise – than a century into our nasogenital past. The eventual historical standing of even our cherished medical and scientific achievements remains, inevitably, to be determined.

What this means in practice is not an open-and-shut case. There is in fact a lively philosophical discussion on the appropriate amount of modesty in science. An influential take was put forward by the philosopher Bas van Fraassen, originally in 1980. He contends that even our most successful scientific theories may have alternatives that fit the same evidence and make the same predictions. Since it would be impossible to tell which is the true one, the aim of scientific enquiry shifts from ambitiously seeking truth to more humbly settling for empirical adequacy. So long as a given theory explains the observable phenomena, we can and should believe in it no more than warranted but no less than needed to make proper use of it. Among those bristling at van Fraassen’s call for radical modesty, a well-liked way to push back is to question the existence of such perfectly equivalent alternatives to our scientific accomplishments. Suppose two theories are indeed able to account for all the same data at present. They are nonetheless likely to diverge over time, such that our more knowledgeable future counterparts will have full confidence in laying to rest one or the other – or both.

It is wise to retain some modesty in matters of science, even when dealing with our most reputable sources

Even so, the challenge persists. In the vividly titled article ‘Do Unborn Hypotheses Have Rights?’ (1981), the philosopher Lawrence Sklar raises the spectre of endless unconceived theories that are not exactly equivalent to our current ones – they are superior. If we were to conjure such a hypothesis, it would supplant the best candidate available to us, and yet it remains unimagined. The history of science seems replete with cases of previously undreamt-of theoretical possibilities swooping in to displace whatever was on offer before. If there are always going to be ‘more theories in Plato’s heaven than have, as yet, been dreamt up by our theoreticians’ (as Sklar puts it), our predicament will perpetually involve some degree of uncertainty. At any given time, we can be pretty sure our scientific theories are better evidenced than past and present rivals, but not the unborn – a point for the (optimistic, yet) forcibly humble.

Admittedly, there is a real sense in which clinical practice cannot accommodate too much uncertainty. A doctor faced with a suffering patient has to act based on whatever information is on hand, posterity be damned. Nevertheless, it is wise to retain some modesty in matters of science, even when dealing with our best, most reputable sources. The philosopher Arthur Zucker describes the roots of our nasogenital derision as follows: we ‘laugh because most scientific preparation is not really preparation for understanding science in an historical context. Rather, it is preparation for learning present-day doctrine.’ If historical literacy skirting present-day judgment is indeed a recipe for humility, I hope to have contributed. Perhaps this way we can begin to set up a collective insurance policy that we ourselves might be seen merely with what Zucker calls ‘friendly laughter and not true scorn’ by those who succeed us. In the meantime, we trudge ahead – doing our best, both fearing and hoping we make enough headway that some of our efforts may (at worst) look silly in the not-so-distant future.

As to Fliess, he was not the first to propose the nasogenital reflex and he was probably not even the first to cauterise someone’s turbinates for menstrual complaints. But our main character would finally rest in peace if we could just give the man credit where he so believed it was due – our universal natural bisexuality.