If you don’t believe in the God of the Bible or the Quran, then you must think we live in a meaningless universe, right? People get stuck in dichotomies of thought. If you don’t like Soviet communism, then you must be in favour of US-style capitalism. Well, not if there are political opinions other than those two (which of course there are). Another dichotomy is between traditional religion and secular atheism. Whose team are you on, Richard Dawkins’s or the Pope’s? Over a long period of time, I’ve come to think that both these worldviews are inadequate, that both have things about reality that they can’t explain. In my book Why? The Purpose of the Universe (2023), I explore the much-neglected middle ground between God and atheism.

I was raised religiously, although the Catholicism of my parents was more about getting the community together than accepting dogmas. From an early age, the secular world all around me was much more of an influence than Sunday school, and by the age of 14 I self-identified as an atheist. It never occurred to me that there was a credible option between these identities: the religious and the secular. Of course, I was aware of the ‘spiritual but not religious’ category, but I was socialised to think this option was unserious and essentially ‘fluffy thinking’. And thus I remained a happy atheist for the next 25 years.

This all changed a mere five years ago when I arrived as a faculty member at Durham University, where I was asked to teach philosophy of religion. It was a standard undergraduate course: you teach the arguments against God, and you teach the arguments for God, and then the students are invited to decide which case was stronger and write an essay accordingly. So I taught the arguments against God, based on the difficulty of reconciling the existence of a loving and all-powerful God with the terrible suffering we find in the world. As previously, I found them incredibly compelling and was reconfirmed in my conviction that there is almost certainly no God. Then I taught the arguments for God’s existence. To my surprise, I found them incredibly compelling too! In particular, the argument from the fine-tuning of physics for life couldn’t be responded to as easily as I had previously thought (more on this below).

This left me in quite a pickle. For me, philosophy isn’t just an abstract exercise. I live out my worldview, and so I find it unsettling when I don’t know what my worldview is. Fundamentally, I want the truth, and so I don’t mind changing my mind if the evidence changes. But here I was with seemingly compelling evidence pointed in two opposing directions! I lost a lot of sleep during this time.

A few weeks into this existential morass I was peacefully watching some ducks quack in a nearby nature reserve, when I suddenly realised there was a startingly simple and obvious solution to my dilemma. The two arguments I was finding compelling – the fine-tuning argument for ‘God’, and the argument from evil and suffering against ‘God’ – were not actually opposed to each other. The argument from evil and suffering targets a very specific kind of God, namely the Omni-God: all-knowing, all-powerful, perfectly good creator of the universe. Meanwhile, the fine-tuning argument supports something much more generic, some kind of cosmic purpose or goal-directedness towards life that might not be attached to a supernatural designer. So if you go for cosmic purpose but not one rooted in the desires of an Omni-God, then you can have your cake and eat it by accepting both arguments.

And thus my worldview was radically changed.

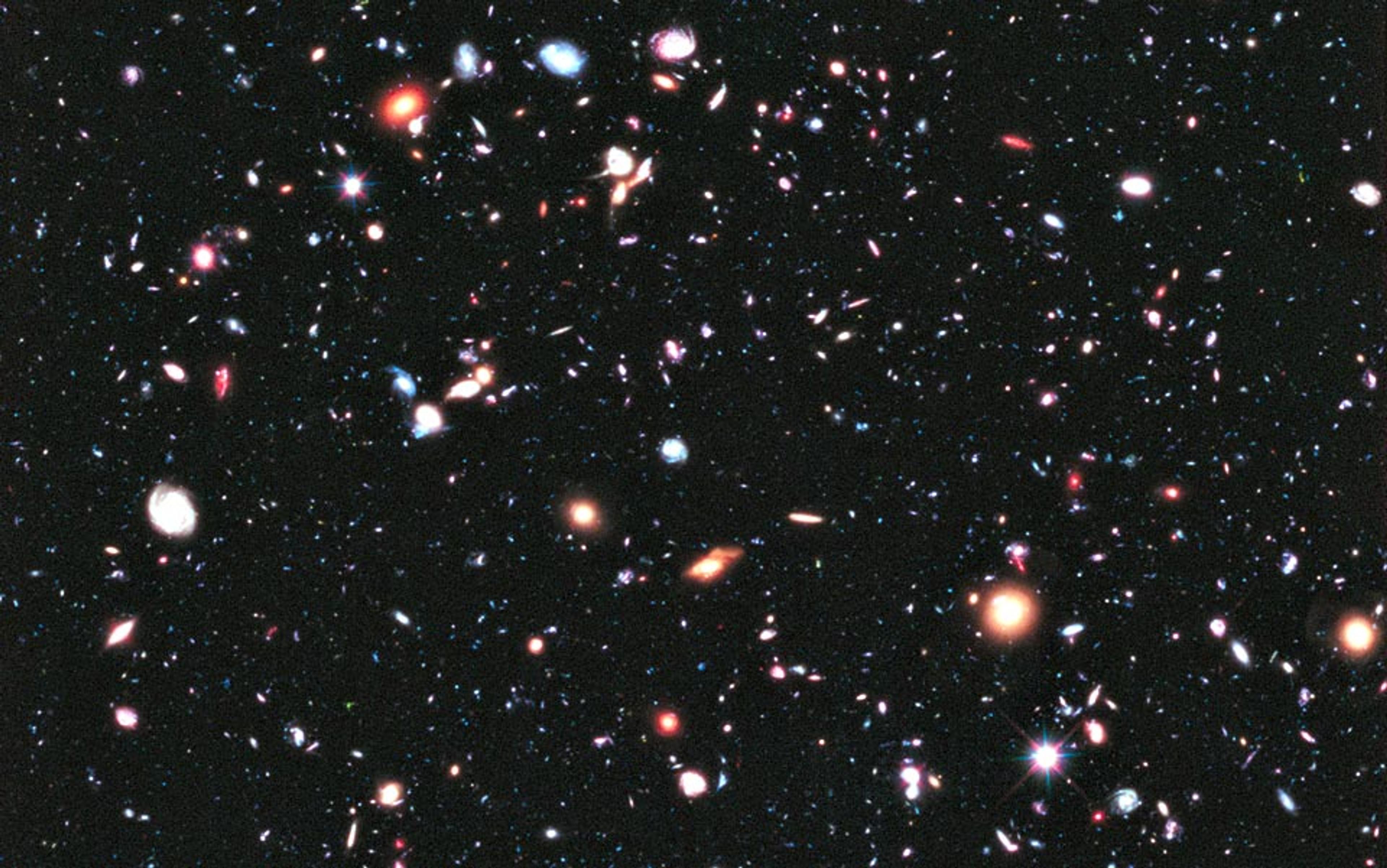

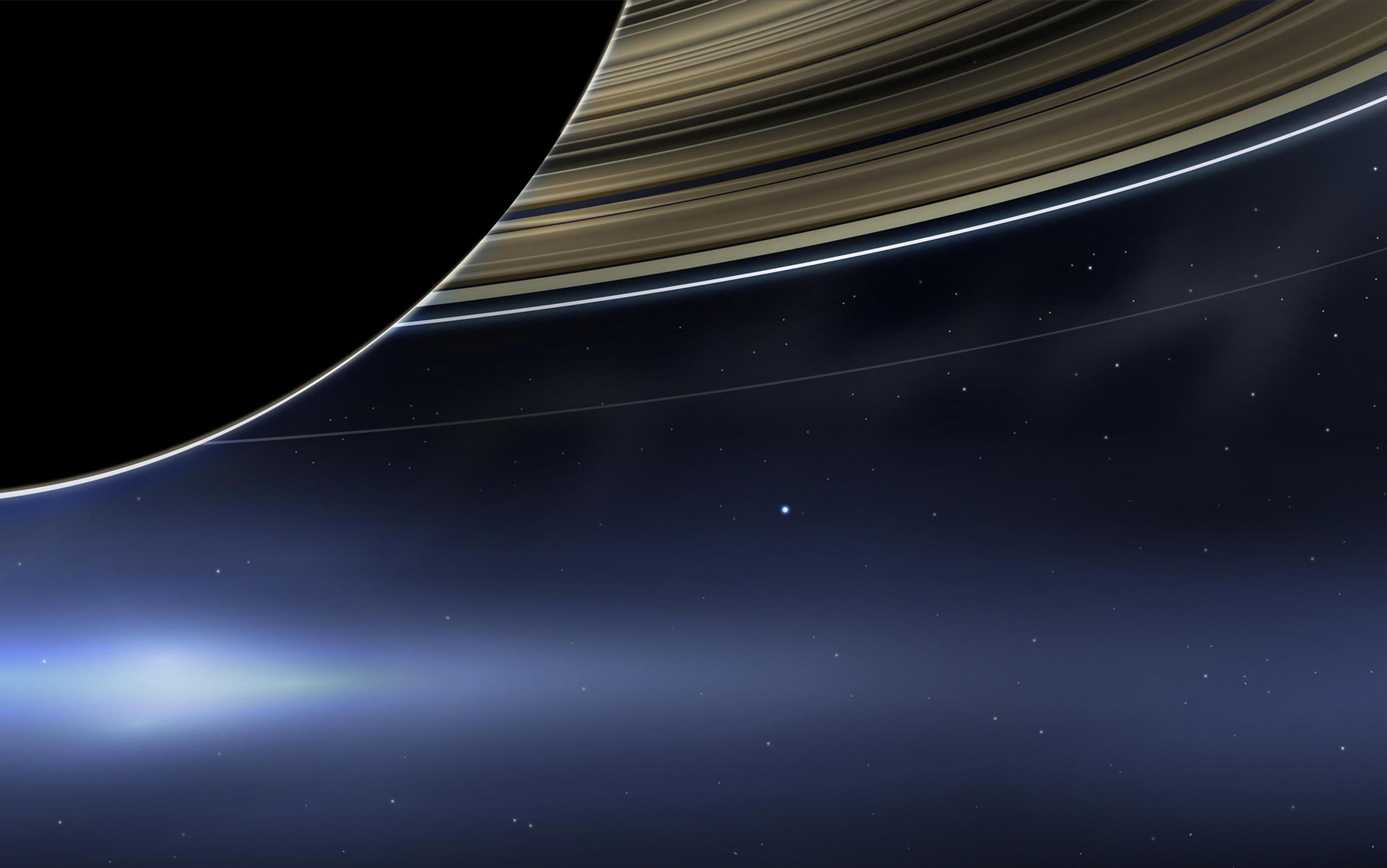

One of the most fascinating developments in modern science is the surprising discovery of recent decades that the laws of physics are fine tuned for life. This means that, for life to be possible, certain numbers in physics had to fall within an incredibly narrow range. Like Goldilocks’s porridge, these numbers had to be just right, not too big and not too small.

Perhaps the most striking case is that of the cosmological constant, the number that measures the force that powers the accelerating expansion of the universe. The cosmological constant is an odd number: it’s extremely small but non-zero. You don’t tend to find fundamental constants with that kind of value. But it’s a good job that it does. Because, if the cosmological constant were a bit bigger, everything would have been forced apart so rapidly that no two particles would ever have met. We would have no stars, no planets nor any kind of structural complexity. On the other hand, if the cosmological constant was less than zero, it would have added to gravity, meaning that the entire universe would have collapsed back on itself within a split second. For life to be possible, this number had to be in the strange, highly specific category it in fact occupies: extremely close to zero without crossing over into the negative. There are many other examples of finely tuned constants in current physics.

Fundamentally, we face a choice. Either:

- it’s a coincidence that, of all the possible values that the finely tuned constants of physics may have had, they just happen to have the right values for life;

or:

- the constants have those values because they are right for life.

The former option is wildly improbable; on a conservative estimate, the odds of getting finely tuned constants by chance is less than 1 in 10-136. The latter option amounts to a belief that something at the fundamental level of reality is directed towards the emergence of life. I call this kind of fundamental goal-directedness ‘cosmic purpose’.

As a society, we’re somewhat in denial about fine-tuning, because it doesn’t fit with the picture of science we’ve got used to. It’s a bit like in the 16th century when we started getting evidence that our Earth wasn’t in the centre of the universe, and people struggled to accept it because it didn’t fit with the picture of the universe they’d got used to. Nowadays, we scoff at our ancestors’ inability to follow the evidence where it leads. But every generation absorbs a worldview it can’t see beyond. I believe we’re in a similar situation now with respect to the mounting evidence for cosmic purpose. We’re ignoring what is lying in plain view because it doesn’t fit with the version of reality we’ve got used to. Future generations will mock us for our intransigence.

Fine-tuning being a fluke is massively more improbable than bank thieves getting a combination right by chance

The most common response online to fine-tuning worries is known as ‘the anthropic response’: if the universe hadn’t had the right numbers for life, we wouldn’t be around to worry about it, and so we shouldn’t be surprised to find fine-tuning. The philosopher John Leslie devised a vivid thought experiment (here presented in a slightly modified version) to show where the anthropic response goes wrong. Suppose you’re about to be executed by five expert marksmen at close range. They load up, take aim, fire… but they all miss. Again, they load up, take aim, fire… again, they all miss. This happens time and time again for more than an hour. Now, you could think: ‘Well, if they had hit me, I wouldn’t be around to worry about it, and so I shouldn’t be surprised that they all missed.’ But nobody would think this. It clearly needs explanation why these expert shooters repeatedly missed at close range. Maybe the guns have been tampered with, or maybe it’s a mock execution. Likewise, while it’s of course trivially true that, if the universe wasn’t compatible with life, we wouldn’t be around to reflect on the matter, it still needs explaining why, of all the numbers in physics that might have come up, a universe ended up with one in the narrow range compatible with life.

Could fine-tuning have been just a fluke? Sometimes, things come together in surprising and unexpected ways, without our feeling compelled to postulate an underlying purpose to reality. But there are limits to this. Suppose thieves break into a high-security bank and get the 10-digit combination right first time. Would it be an option to say: ‘Well, maybe they just randomly tried a number and it just happened to be the right one’? This would clearly be an irrational thing to think, as it’s just too improbable that they would get the combination right by fluke. But the fine-tuning being a fluke is massively more improbable than the thieves getting the combination right by chance. Taking fine-tuning to be a matter of luck is just not a rational option.

But aren’t there many incredibly improbable things we accept as just chance? My existence depends on an incredibly finely tuned set of circumstances: my parents having met, and their parents having met, and so on back to the start of humanity. Indeed, if a different sperm had fertilised the egg that produced me, I would not be here. It can induce a sense of vertigo to reflect on how unlikely it is that one should ever have existed. And yet, while I believe there is a cosmic directedness towards life, my ego is not (yet!) inflated enough to suppose that there was a cosmic directedness towards Philip Goff coming into being. What’s the difference?

The difference is that life has objective value, and hence is an outcome of significance independently of it being the outcome that happened to occur. A universe in which there are plants and animals, and people who can fall in love and contemplate their own existence, is much greater than a universe in which there is only hydrogen. In this sense, the numbers consistent with such valuable happenings are special in a way that other possible values of the constants are not. In contrast, there’s nothing particularly special about Philip Goff existing, as opposed to whoever would have been here if, say, my father had married someone else.

To make the point clearer with an analogy, contrast the case in which some random person, Jo Bloggs, wins the lottery, with the case in which Mr Rich, the partner of the lottery boss, wins the lottery. Jo Bloggs is noteworthy only as a result of winning the lottery, and hence we can accept that her win was a fluke. This is a bit like the case of me being born as opposed to some other random individual. But there is a significance to Mr Rich independently of the fact that he won: he’s the partner of the lottery boss. And so, when, of all the people who might have won, Mr Rich wins, we suspect foul play. Likewise, when, of all the possible numbers that might have turned up in physics, we have a rare combination that allows for objective value to emerge, we rightfully suspect that this is more than just fluke.

I often find, when I discuss the fine-tuning on Twitter, people express a sentiment that it’s brave to boldly accept something so improbable, like you’re not scared to take it on. But it’s not brave to believe highly improbable things, it’s irrational. In my view, a commitment to cosmic purpose is the only rational response to the evidence of current science.

God provides an explanation of fine-tuning, but a very poor one. Maybe for our ancestors it made sense that a God who was so much greater than us could do what he liked with his creatures. But moral progress has taught us that each individual has fundamental rights that nobody, no matter how powerful and cognitively sophisticated, is permitted to infringe.

In my book Why? I focus on the work of the great philosopher of religion Richard Swinburne in responding to the problem of evil. Swinburne argues that there are goods that exist in our universe that would not exist in one with less suffering. If we just lived in some kind of Disneyland-esque world with no danger or risk, then there would be no opportunities to show real courage in the face of adversity, or to feel deep compassion for those who suffer. The absence of such serious moral choices would be a great cost, according to Swinburne.

Even if we concede that this is indeed a cost, I don’t believe that God would have the right to cause or allow suffering in order to allow for these goods. A classic argument against crude forms of utilitarianism imagines a doctor who could save the lives of five patients by killing one patient and harvesting their organs. Even if the doctor could increase wellbeing in this way, he would not have the right to kill and use the healthy patient, at least not without their consent. Likewise, even if God has some good purpose in mind for allowing natural disasters, it would infringe the rights to health and security of the individuals impacted by such disasters.

Maybe our limited designer feels awful about how messy such a process inevitably is, but it was that or nothing

Fortunately, there are other possibilities. Thomas Nagel has defended the idea of teleological laws: laws of nature with goals built into them. Rather than grounding cosmic purpose in the desires of a creator, perhaps there just is a natural tendency towards life inherent in the universe, one that interacts with the more familiar laws of physics in ways we don’t yet understand.

For some, the idea of purpose without a mind directing it makes no sense. An alternative possibility is a non-standard designer, one that lacks the ‘omni’ qualities – all-knowing, all-powerful, and perfectly good – of the traditional God. What about an evil God? As Stephen Law has explored in detail, the evil-god hypothesis faces a ‘problem of good’ mirroring the problem of evil facing the traditional good God: if God is evil, why did God create so much good? I think a better option is a limited designer who has made the best universe they are able to make. Perhaps the designer of our universe would have loved to create intelligent life in an instant, avoiding all the misery of natural selection, but their only option was to create a universe from a singularity, with the right physics, so that it will eventually evolve intelligent life. Maybe our limited designer feels awful about how messy such a process inevitably is, but it was that or nothing.

A supernatural designer comes with a parsimony cost. As scientists and philosophers, we aspire to find not just any old theory that can account for the data but the simplest such theory. All things being equal, it’d be better not to have to believe in both a physical universe and a non-physical supernatural designer.

For these reasons, I think overall the best theory of cosmic purpose is cosmopsychism, the view that the universe is itself a conscious mind with its own goals. In fact, this is a view I first entertained in Aeon back in 2017, before deciding that the multiverse, the topic of the next section, was a better option. Having been finally persuaded that the multiverse is a no-go (more on this imminently), I was prompted to explore a more developed cosmopsychist explanation of fine-tuning in my book Why?, and this now seems to me the most likely source of cosmic purpose.

Warning: the next section is a little technical, and can be skipped over, at least on first reading.

There are many scientists and philosophers who share this conviction that the fine-tuning of physics can’t be just a fluke, but who think there is an alternative explanation: the multiverse hypothesis. If there is a huge, perhaps infinite, number of universes, each with different numbers in their physics, then it’s not so improbable that one of them would happen to have the right numbers by chance. And we surely don’t need an explanation of why we happened to be in the fine-tuned universe; after all, we couldn’t have existed in a universe that wasn’t fine-tuned. The latter part of the explanation is known as the ‘anthropic principle’.

For a long time, I thought the multiverse hypothesis was the most plausible explanation of fine-tuning. But I eventually became persuaded through long discussions with probability theorists that the inference from fine-tuning to a multiverse involves flawed reasoning. This is a much-discussed issue in philosophy journals but, in a typical case of academics talking to themselves, it is almost entirely unknown outside of academic philosophy, despite huge public interest in the issue of fine-tuning. One of my motivations for writing the book Why? was to convey this argument, which changed my life, to a broader audience.

There’s a crucial principle in probabilistic reasoning known as the ‘total evidence requirement’. This is roughly the principle that we should always use the most specific evidence available to us. Suppose the prosecution tells the jury that the accused always carries a knife around with him, neglecting to add that the knife in question is a butter knife. The prosecution has not lied to the jury, but it has misled them by giving them generic information – that the accused carries a knife – when it could have given them more specific information – that the accused carries a butter knife. In other words, the prosecution has violated the total evidence requirement.

Respecting the total evidence requirement renders the inference to a multiverse invalid

How does this principle relate to fine-tuning and the multiverse? It’s relevant because there are two ways of interpreting the evidence of fine-tuning:

- generic evidence: a universe is fine-tuned; or

- specific evidence: this universe is fine-tuned.

The multiverse theorist works with the generic way of construing the evidence. They have to do this to infer from fine-tuning to a multiverse. The existence of many universes makes it more likely that a universe will be fine-tuned, but it doesn’t make it any more likely that this universe in particular – as opposed to, say, the next universe down – will be fine-tuned. Hence, the multiverse hypothesis is supported only if one works with the generic way of construing the evidence. But this is in conflict with the total evidence requirement, which obliges us to work with the more specific form of the evidence, namely that this universe is fine-tuned. Respecting the total evidence requirement, therefore, renders the inference to a multiverse invalid.

We can make the point clearer with an analogy. Suppose we walk into a casino and the first person we see, call her Sammy Smart, is having an incredible run of luck, calling the right number in roulette time after time. I say: ‘Wow, the casino must be full tonight.’ Naturally, you’re puzzled and you ask me where I’m getting that idea from. I respond: ‘Well, if there are a huge number of people playing in the casino, then it becomes statistically quite likely that at least one person in the casino will win big, and that’s exactly what we’ve observed: somebody in the casino winning big.’

Everyone agrees that the above is a fallacious inference, and the reason it’s fallacious is that it violates the total evidence requirement. There are two ways of construing the evidence available to us as we walk into the casino:

- generic evidence: someone in the casino has had a great run of luck; or

- specific evidence: Sammy Smart has had a great run of luck.

In the above scenario, my strange reasoning essentially involved working with the generic way of construing the evidence: it is indeed more likely that someone in the casino had a great run of luck if we hypothesise that there are many people playing well in the casino. But, again, the total evidence requirement obliges us to work with the more specific way of construing the evidence – Sammy Smart had a great run of luck – and, once we do this, the inference to a full casino is blocked: the presence or absence of other people in the casino has no bearing on whether or not Sammy Smart in particular will play well. The reasoning employed by the multiverse theorist makes exactly the same error. To respect the total evidence requirement, we need to work with the specific version of the evidence – that this universe is fine tuned – and the presence or absence of other universes has no bearing on whether or not this universe in particular turns out to be fine tuned.

Many argue that this is where the anthropic principle kicks in. While we could have entered the casino and observed someone rolling badly, we could not have observed a universe that wasn’t compatible with life.

But isn’t there independent scientific evidence for a multiverse? Yes and no

It is of course trivially true that we could not have observed a universe incompatible with the existence of life. But no theoretical justification has ever been given as to why this would make it OK to ignore the total evidence requirement. Moreover, we can easily insert an artificial selection effect into the casino example by imagining there’s a sniper hidden in the first room of the casino, waiting to kill us as we enter unless there is someone in the first room having an extraordinary run of luck. With this in place, the casino example is relevantly similar to the real-world case of fine-tuning: just as we could not have observed a universe with the wrong numbers for life, so we could not have observed a player rolling the wrong numbers to win. And yet, nobody disputes that the casino example involves flawed reasoning, reasoning that, in my view, is indiscernible from that of the multiverse theorist.

But isn’t there independent scientific evidence for a multiverse? Yes and no. There is tentative support for what cosmologists call ‘inflation’, the hypothesis that our universe began with a short-lived exponential rate of expansion. And many physicists have argued that, on the most plausible models of inflation, the exponential expansion never ends in reality considered as a whole, but ends only in certain regions of reality, which slow down to become ‘bubble universes’ in their own right. On this model, known as ‘eternal inflation’, our universe is one such bubble.

The problem is that there are two possible versions of eternal inflation:

- heterogenous eternal inflation – when a new bubble forms, probabilistic processes determine that the values of the constants, and so the vast majority of bubble universes, are not fine tuned; or

- homogenous eternal inflation – the values of the constants do not vary between bubble universes.

Pretty much all multiverse theorists assume heterogenous eternal inflation, which is probably because only this version can have a hope of explaining away fine-tuning. Only if there’s enough variety in the ‘local physics’ of different bubble universes does it become statistically likely that the fine-tuning is just a fluke. But there is zero empirical evidence for this. Moreover, if we respect the total evidence requirement, then the fine-tuning itself is powerful evidence against heterogenous eternal inflation.

Remember that the total evidence requirement obliges us to work with the specific way of construing the evidence of fine-tuning:

- specific evidence: this universe is fine-tuned.

According to our standard mathematical way of defining evidence – known as the Bayes theorem – a hypothesis fits with data to the extent that the hypothesis makes the data probable. If heterogenous eternal inflation were true, it would be incredibly unlikely that our universe would be fine tuned, as the probabilistic processes that fix the constants of each universe are entirely random. But if we combine homogenous eternal inflation with some form of cosmic goal-directedness towards life, then it becomes massively more likely that our universe will be fine tuned.

In other words, even if we adopt the eternal inflation multiverse, the evidence of fine-tuning still pushes us towards cosmic purpose.

The Christian philosopher William Lane Craig has argued that, if the universe has no purpose, then life is meaningless. Along similar lines, the atheist philosopher David Benatar proposes that, in the absence of cosmic purpose, life is so meaningless that we are morally required to stop reproducing so that the human race dies out. At the other extreme, it is common for humanists to argue that cosmic purpose would be irrelevant to the meaning of human existence.

I take a middle way between these two extremes. I think human life can be very meaningful even if there is no cosmic purpose, so long as we engage in meaningful activities, such as kindness, creativity and the pursuit of knowledge. But, if there is cosmic purpose, then life is potentially more meaningful. We want our lives to make a difference. If we can contribute, even in some tiny way, to the good purposes of the whole of reality, this is about as big a difference as we can imagine making.

There are no certain answers to these big questions of meaning and existence. It’s possible the abundant evidence for cosmic purpose in our current theories will not be present in future theories. Even if there is a fundamental drive towards the good, without an omnipotent God, we have no guarantee that cosmic purpose will ultimately overcome the arbitrary suffering of the world. But it can be rational, to an extent, to hope beyond the evidence. I don’t know whether human beings will be able to deal with climate change; in fact, a dispassionate assessment of the evidence makes it more likely perhaps that we won’t. Still, it’s rational to live in hope that humans will rise to the challenge, and to find meaning and motivation in that hope. Likewise, I believe it’s rational to live in hope that a better universe is possible.

Why? The Purpose of the Universe (2023) by Philip Goff is published via Oxford University Press.