It began in late September 2022. I was just recovering from a severe case of COVID-19 when Hurricane Ian hit my hometown in southwest Florida. My wife and I evacuated to Miami for a week and watched the damage unfold on various news channels. When we returned to our home in Fort Myers a week later, we were shocked by the devastation. The scenes were absurd. There were huge fishing boats suspended like toys from mangrove and palm trees, entire homes floating in the middle of San Carlos Bay, the famous causeway to Sanibel Island ripped in half, and the town of Fort Myers Beach utterly flattened. But our house, albeit without power, made it through the storm relatively unscathed.

One evening amid the power outage, I happened to be outside on the patio reading by headlamp when I began noticing my jaw clenching and tightening up. I was suddenly having difficulty controlling my tongue, lips and jaw. I came inside and asked my wife if I might be having a stroke. Beyond my Covid experience and the wreckage of the hurricane, this was an extremely stressful time in my life. As a philosophy professor, I had just published a new book that was generating a modest buzz, and it seemed as if I was being invited to give talks all over the place. Always an anxious traveller, I was scheduled to fly in rapid succession from Madison, Wisconsin to Birmingham, England and then to Sweden for a talk in Stockholm, then to Linköping for another talk and back to Stockholm again for a third. This, in addition to my normal work duties and some major upheavals in my personal life, appeared to short-circuit me physically and emotionally.

My first thought was that I had temporomandibular joint disorder (TMJ) from excessive jaw clenching. I scheduled appointments with numerous dentists, who confirmed that I was a jaw clencher and created an occlusion splint to wear at night. But the movements continued, and the pain was getting worse. My tongue was moving constantly, and I noticed it affecting my speech with slurring and a pronounced lisp. I started chewing gum to occupy my tongue. The anxiety about what was happening to my body reached such a breaking point that I cancelled all my trips and gave my talks virtually via Zoom. I scheduled an appointment with a psychiatrist, who recommended I up the dose of the antidepressant Zoloft, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), a version of which I had been taking for well over two decades. But things got only worse. The increased dose of Zoloft made me feel dissociated and dangerously impulsive. Ativan was added to help take the edge off, but the spiral of depression and anxiety deepened. I considered checking into a psychiatric hospital. What was happening to me?

In a panic, I went to the emergency department of the local hospital to be checked out and was quickly dismissed as someone suffering from work-related stress and maybe needing some botulinum toxin injections (‘Botox’) to ease the movement of my jaw. Then my wife began to do some research and suggested that perhaps the uncontrolled facial movements were the result my long-term use of SSRIs, the dosage of which I had just increased. I was unconvinced, assuring her that those kinds of side-effects came from antipsychotic and neuroleptic medications, not the relatively benign SSRIs that nearly every friend and colleague I knew had taken at one time or another. But then I started doing some digging and read reports that, although rare, an abnormal movement disorder called tardive dyskinesia (TD) could emerge from long-term use of SSRIs. I went back to the emergency department the next day, received blood work and a CT scan, all of which came back normal, with a suggestion that it may in fact be TD, and a referral to a neurologist. It was at this point that I officially entered the dehumanising maze of the biomedical industrial complex and encountered the so-called ‘blind spot’ in neurology, where a neurological disorder exists that is incompatible with neurological disease.

The first neurologist (neurologist #1) I saw gave me a thorough exam and concluded that my symptoms were not consistent with TD because of their sudden onset, because I was not taking antipsychotic or neuroleptic drugs, and because SSRI-induced TD was exceedingly rare. She chalked it up to acute situational stress and gave me the diagnosis of ‘functional neurological disorder’ (FND), formerly known by psychiatrists as hysteria or conversion disorder, where psychological symptoms are ‘converted’ to physical symptoms. In recent years, the condition has been referred to in different contexts as psychogenic disorder, somatoform disorder, and even ‘medically unexplained symptoms’ (MUS). Researchers and clinicians today tend to support the term ‘functional neurological disorder’ because it is purely descriptive, covers a range of different symptom presentations, and is agnostic in terms of aetiology, the idea being that there is a problem with the functioning of the nervous system, but it doesn’t have a structural cause.

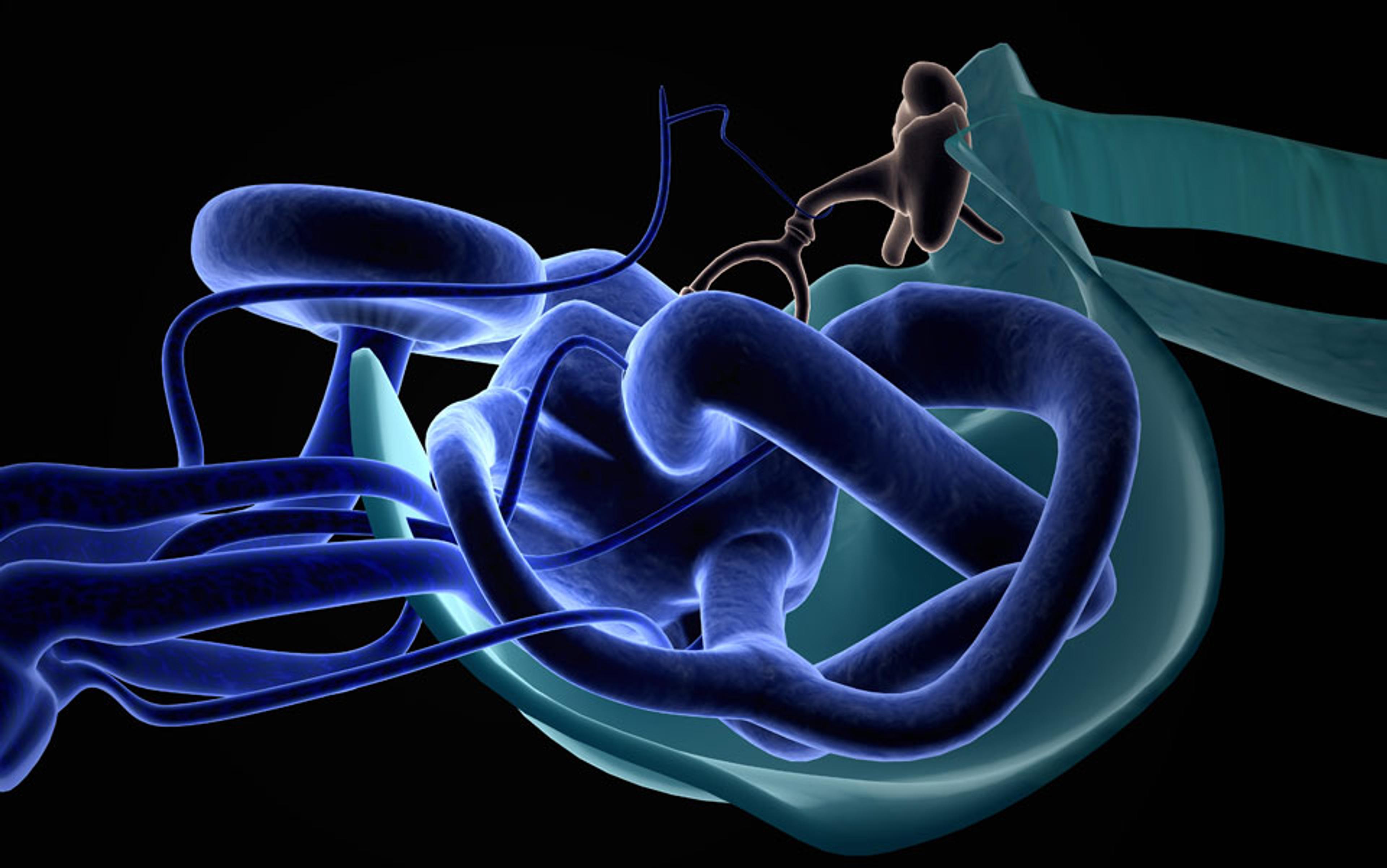

The idea taps into a computer analogy: there is a software issue in the brain, not a structural or hardware issue (as might occur with Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, or multiple sclerosis). The software problem, whatever that is, can lead to involuntary movements, gait disturbances, dissociative episodes, non-epileptic seizures, muscle weakness and fatigue, and, in my case, speech problems not explained by other medical or psychiatric conditions.

After giving me the diagnosis, neurologist #1 left the examination room offering no recommendation for treatment, medical or otherwise, except to find a good psychiatrist. Seeking a second opinion, I went to neurologist #2 who also gave me a thorough exam but disagreed that my condition could be so quickly diagnosed as functional. He thought it could be TD or FND among a host of other things but was admittedly not skilled or experienced enough as a movement disorder specialist to make a proper diagnosis. Suspecting a stroke, he ordered an MRI (which came back normal), recommended that I go to a university research hospital, and put me on a trial of Austedo, one of the new medications that may reverse or lessen TD symptoms.

In the meantime, my new (and more thoughtful and experienced) psychiatrist disagreed with the TD diagnosis, claiming that in his 25 years of practising psychiatry he’d seen very few cases of SSRI-induced TD. He also didn’t want to dismiss the possibility that my exposure to the coronavirus may be playing a role and, like neurologist #2, suggested a visit to a research university for an expert opinion.

Finding such an expert was no easy task. Most research universities and treatment centres had at least a six-month waiting list and some, like the Mayo Clinic, refused to see me at all. Being held in a state of diagnostic limbo for months was deeply demoralising and left me feeling increasingly anxious and alone. After much string-pulling, my wife was finally able to get an appointment with a movement disorder specialist at Duke University and we flew to Durham, North Carolina with the hope of getting some clarity. Here, neurologist #3 gave a rather quick diagnosis of TD and suggested that I get off the dopamine-affecting Zoloft, replaced by daily doses of ginkgo biloba and the benzodiazepine Klonopin. She recommended a trial of a different medication for TD called Ingrezza (as the Austedo did not appear to work). She also scheduled me for Botox treatments around my face to diminish the lip and jaw movement, but warned the movement disorder could be permanent.

I left each consultation feeling more anxious and alone … I became suicidal for the first time in my life

My psychiatrist reluctantly followed the lead of the Duke neurologist, but I was still unconvinced of the TD diagnosis, so I sought yet another opinion. Once again, this meant many months of waiting until I finally received a consultation from the Norman Fixel Institute for Neurological Diseases at the University of Florida. Here, neurologist #4 gave a much more thorough exam than the others and videotaped the entire procedure so she could share it with colleagues who were also movement disorder specialists. That team rejected the TD diagnosis, concluding that my symptoms were far more consistent with FND – explaining why neither the Austedo nor the Ingrezza worked. Although I appreciated the rigour and comprehensiveness of the examination, no treatment plan was offered, my symptoms were getting progressively worse, and my mental state was deteriorating. I was uncertain about whose diagnosis to trust. Was I suffering from TD, FND, or something else?

Having suffered a massive heart attack in my late 40s, I am no stranger to dealing with health emergencies. But this experience has been different in kind. With a heart attack there are clear medical interventions, in my case, an angioplasty and a strict medication protocol. But over the span of a year and half, the many neurologists I saw didn’t just not know how to treat me; they couldn’t even come to a consensus about what I had. I left each consultation feeling more anxious and alone, to such a degree that I became suicidal for the first time in my life.

I slogged through my days and weeks trying to cope with my condition. My mouth, jaw and tongue felt uncanny, like foreign objects that didn’t belong to me and that I had no control over. This lack of control affected my ability to move through the world, anticipate future projects or even relate to others in my life. All of it was collapsing.

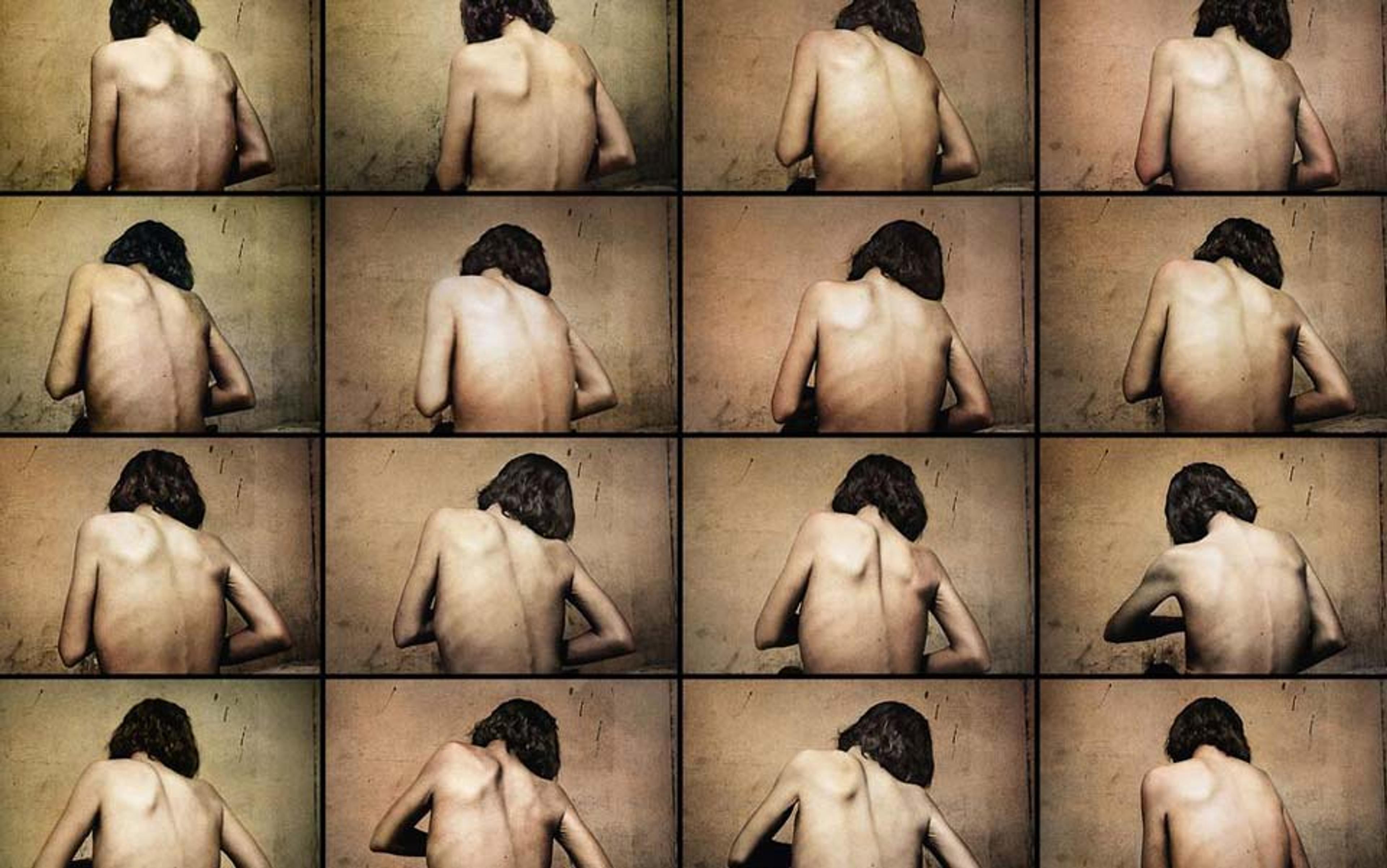

The first thing I noticed as my world collapsed was how I thought others looked at me. Involuntary movement disorders are cruel and disabling conditions that can result in profound feelings of shame. But, in my case, shame was not directed at a specific event or object. It was more of a global experience, an atmospheric feeling colouring my whole existence. I began thinking of Jean-Paul Sartre, who claimed that our self-perception is always mediated by ‘the look’ (le regard) of the other. In Being and Nothingness (1956), he wrote:

I am possessed by the other; the other’s look fashions my body in its nakedness, causes it to be born, sculptures it, produces it as it is, sees it as I shall never see it. The other holds a secret – the secret of what I am.

These words spoke to me in a powerful way. I found myself exposed and vulnerable to the look, and began socially isolating as my orofacial movements worsened, especially when they began to affect my speech. I moved my classes online, attended meetings virtually, and often left my office door shut. The look of the other was too much. Hearing my experience, neurologist #2 said, without a hint of compassion that I could detect: ‘That sounds like a living hell.’ And he was right. But the hell emerged not merely because I felt besieged by the objectifying stares of others, but also because I was internalising these stares and interpreting myself as monstrous.

As my condition progressed, I found I could no longer eat without food falling out of my mouth, and I could no longer lecture with any of the fluency and precision that I had long taken for granted. The body that had propelled me effortlessly forward through a kind of tacit proprioception, what Maurice Merleau-Ponty called the ‘I can’ (je peux), was replaced with an awkward and debilitating sense of ‘I can’t’. This experience kept me from dissolving into the flow of everyday life, transforming me into what Sartre called a ‘body-for-others’ (corps pour autrui), a stigmatised object, self-conscious and filled with shame. And the more I internalised this judgment, the more I was sucked into a feedback loop of isolating behaviour and feelings of self-reproach that further intensified my suffering. I found myself chewing gum in a desperate attempt to disguise the uncontrolled jaw and tongue movements, and even took comfort in wearing pandemic masks when out in public. All of this illuminates the ways in which shame is fundamentally a social mood, felt by embodied beings who inhabit a shared world.

Prior to the onset of symptoms, space felt open and expansive to me; the dinner party at a colleague’s house, the trip to the gym or the grocery store, even the vacation abroad, all presented themselves as activities that were navigable. But in the grip of the disorder, my seamless ability to stretch into the world broke down. The horizon of my life began to contract as I found myself avoiding social gatherings, refusing invitations to give public lectures, and spending more time at home or behind the closed door of my office.

There is often a trigger, such as a traumatic event, psychological stress or illness that sets things in motion

All this made it difficult to envision a meaningful future. In his meditations on time, Martin Heidegger claims that we are always running ahead of ourselves toward possibilities not yet realised. But my previously expansive future of anticipated plans and projects was abruptly shuttered, and the weeks and months ahead looked increasingly dark and unclear. I became unsure, for example, if I could sustain my work as a professor. If much of my identity as an academic was built around my verbal acuity, my ability to give lectures, teach and communicate effectively with colleagues, I was left wondering: ‘Who am I now?’ The confidence and ease that I previously embodied in front of students in the classroom, in department meetings or at professional conferences was all but gone.

Most fundamentally, the question of what I suffered from remained. In the end, I decided that neurologist #4 at the University of Florida probably had the correct diagnosis, that I didn’t have TD but FND, today understood as more than a diagnosis of exclusion. For instance, there is often a trigger, such as a traumatic event, psychological stress or illness that sets things in motion. I had experienced all these things in the span of a few weeks. And once the software has been disrupted and the neurological disorder has kicked in, there are positive ways that the diagnosis can be made. In my case, neurologist #4 noticed that if I performed certain complex tasks that distracted me, such as moving my left foot around in a counterclockwise direction while reciting the alphabet backwards, the movement of my tongue and mouth stopped.

In the language of FND, this is called ‘distractibility’, and it suggests that the brain and mind work best together when we are less preoccupied with their functioning. Distractibility generally doesn’t work if there is a structural pathology. But just because the condition is functional (and perhaps even reversible) did not make the diagnosis any easier for me.

I was beginning to see the limits of what biomedicine could do.

We are living in an age where disease management is increasingly technical and, as it becomes more specialised, the human being is progressively mathematised, viewed less as a whole person than a collection of data points subject to management and control. In the face of the Promethean ethos of biomedicine, FND represents what Hans-Georg Gadamer in The Enigma of Health (1996) called a ‘sphere of the unrationalised’ (Bereich des Unrationalisierten), an ailment that can’t (yet) be located or measured with a blood test, CT scan or MRI, one that falls outside the domain of technological mastery and control. There are no medications to treat it, so the pharmaceutical industry is uninterested; there are no surgical procedures to reverse it, so physicians are often mistrustful and dismissive.

Indeed, FND has been, until very recently, largely invisible in neurology. As Jon Stone, a neurologist at the University of Edinburgh in the UK, and a pioneer in clinical research and advocacy for FND, told me, the condition basically ‘disappeared from neurology textbooks for a century; it didn’t appear in training, and hardly any neurologists are getting an education on FND.’ He went on to add that ‘in many cases, people don’t even get a diagnosis at all, the neurologist will just say: We can’t find anything wrong with you.’

It is no coincidence, then, that patients often report psychologically and physically harmful experiences in clinics and hospitals, feeling belittled and marginalised because their symptoms were considered medically unreal or, worse, they were suspected of malingering, of feigning symptoms for attention or some other reward. They were often not only not believed, but sometimes even laughed at. ‘The communication of the condition between neurologist and patient has been appalling,’ says Stone, ‘and it still is.’

Sufferers describe being dismissed not just by the medical community but by family and friends

Even as new findings reveal ways to identify the condition, many neurologists lack the interest or the training. The result is that the diagnosis is still arrived at largely through a process of exclusion, leaving patients feeling like medical orphans. ‘Neurologists often tell the FND patient what they don’t have, which isn’t helpful to the patient… [They think] my job is just to tell the person that they’ve got no neurological disease, then refer them to a psychiatrist.’

The strategy is deeply unhelpful. Sufferers describe feelings of isolation, shame and loneliness, of being dismissed not just by the medical community but by family and friends. Some have even expressed a wish for a terminal diagnosis rather than FND because at least then their suffering would be accepted as medically legitimate. As one exhausted woman put it: ‘I just want permission to be ill.’

The difficulty with FND is that there is extremely limited access to evidence-based treatment, and, as Mark Edwards, professor of neurology at King’s College London, told me: ‘The treatments that we do have are still in their infancy.’ Maddening: a disease with poorly understood mechanisms and a complex, context-specific presentation that varies from one individual to the next. It is well known, for example, that women are disproportionately affected by FND with rates that are two to three times higher than in men, and recent studies have found that most patients with functional seizures live in impoverished areas, highlighting the importance of socioeconomic background.

Belonging to the ‘sphere of the unrationalised’, FND compels us to rethink the long-held boundary between mind and body, and challenges the assertion that without an organic biomarker, the condition must be psychological. Stone makes it clear that FND ‘sits at the interface between mind and brain’ and that the demarcation between neurological and psychological is essentially meaningless. In reviewing my own case history, there certainly were psychological stressors, and mental illness runs like a river through my family. But in many cases of FND there are no psychological factors. And, even if there are, they may not be relevant to the symptoms at hand.

For physicians, a diagnosis of FND is often the end of the story. But for patients like me, it marks the beginning of a long, uncertain quest for recovery and relief. My own search has convinced me that the answer is multidisciplinary and holistic. Yet this holistic approach is something that every neurologist, physician and psychiatrist I’ve encountered has neglected. Nowhere did I find coordination of care between neurology, psychiatry, speech pathology, physical and occupational therapy, or psychotherapy.

Indeed, after my diagnosis at the University of Florida, all neurologist #4 could offer was a website that Stone helped develop, called Neurosymptoms. I was left on my own to cobble together an individualised course of care, but quickly realised that the therapists I was coordinating had very little (if any) understanding of the FND turf.

This is what has energised much of Stone’s advocacy over the years. ‘There must be millions of people with the condition,’ he says, ‘and they are treated really badly.’ Edwards expressed the same frustration, telling me bluntly that ‘FND is incredibly common, it is really disabling, and it’s ruining many people’s lives.’ Despite the frequency of the condition and the life-altering nature of the symptoms, patients suffering from FND are passed along from doctor to doctor, often waiting years to receive some form of treatment. It took me eight months, four neurological consultations and two research universities to finally get an accurate diagnosis – and I was fortunate. A recent study has shown that the mean time for a diagnosis of patients suffering from functional seizures is eight years. This is unacceptable, and points to the enormous practical and clinical value of giving voice to those suffering from FND, where rates of distress, disability and loss of identity are similar to those with ‘real’ neurological conditions like epilepsy, multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease.

My hope is that personal narratives like mine might help reduce the stigma of FND and shed light on the extent to which long-overdue public awareness, chronic underfunding, delayed diagnosis and limited treatment access remain unacceptable. As Stone says: ‘If we just stopped harming people, that would be a start.’

The condition is finally emerging into public view after a century in the dark

Fortunately, there is a sea change taking place. Stone and Edwards point to the international FND Society, which now has more than 1,300 members devoted to improving diagnosis and treatment. Beyond that, and enormously significant, FND has become one of the eight core topics in the UK neurology curriculum, one of the 19 core topics in the European Academy of Neurology, and part of the curriculum in the American Academy of Neurology. And with a growing list of Facebook groups providing social support and information-packed websites like FND Hope and FND Portal, the condition is finally emerging into public view after a century in the dark.

It is also true that, with advanced neuroimaging, the presence of FND is no longer banished to an immaterial netherworld; traces of the condition can now actually be seen in the brain. There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that brain abnormalities associated with motor hysteria and emotion regulation may be visible with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), demonstrating that FND is, in fact, a ‘real’ brain disease. But these findings need to be viewed with caution. Data gathered from fMRI are notoriously imprecise and unreliable. In a meta-analysis of 56 articles examining the reliability of fMRIs, Ahmad Hariri, professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University, makes it clear that the ‘correlation between one scan and a second is not even fair, it’s poor.’ In other words, an fMRI scan in its current form is unable to predict what an individual’s brain activity will look like from one scan to the next, and, of course, it remains unclear whether a given brain abnormality is the cause or the consequence of FND. To be clear, neuroscience is still very much in its infancy when it comes to unlocking the mystery of how neurons produce feelings, thoughts and movements.

Alas, I’m still searching for adequate treatment and on the lookout for a speech pathologist or neuropsychologist with formal training and expertise in FND. In the meantime, I realise that the only way forward is to learn to accept my condition as it is now, to have compassion for myself and my malfunctioning mouth, and to continue moving toward the things that I am afraid of.

Part of this path to acceptance was to get out in front of audiences and talk again – slurred speech, flailing tongue and all. A pivotal moment came at an interdisciplinary conference at the University of Wisconsin, Madison in the fall of 2023, about a year to the day that I began suffering from symptoms. I was terrified of embarrassing myself, but I walked to the podium and, before I began, openly and honestly described my condition to the audience.

Appropriately titled ‘Wellness, Burnout, and the Conditions of American Work’, the talk went over beautifully, and the support from participants over the next few days was extraordinary. I made lasting friendships, and I’m convinced that my willingness to be vulnerable about my health struggles made an important difference in how both I and my work were received.

Another important move in the direction of self-acceptance – one that I would certainly not recommend to everyone suffering from FND – was a session of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy in Boulder, Colorado. There is a growing body of research showing that psychedelic treatment may be effective in treating depression, PTSD and anxiety, and perhaps even diminish symptoms of FND. My intention for treatment was to dismantle the ego-driven need for perfection and control that was tormenting me, and to let go of the ruminating grief I was holding onto at the loss of my old self.

Taking a so-called ‘heroic’ dose of psilocybin, the five-hour journey was profound: I was flooded with indescribable feelings of love, tenderness and forgiveness, and an immediate and direct awareness of the interdependence of all things.

My therapist recorded me at the peak, lying with eye mask and headphones on, sobbing and writhing in ecstasy, saying over and over: ‘The glory… the glory… let me share.’ Whether or not this experience of transcendence endures remains to be seen, but there is finally light coming in through a crack in the door. Eating yoghurt and granola in the aftermath, food once again fell out of my mouth. But my reflexive response of despair and frustration was absent.

Instead, I found myself smiling – then laughing. I was finally seeing my disorder, and my life, from a much wider lens – and from a cosmic perspective, none of it really mattered. That makes a difference.