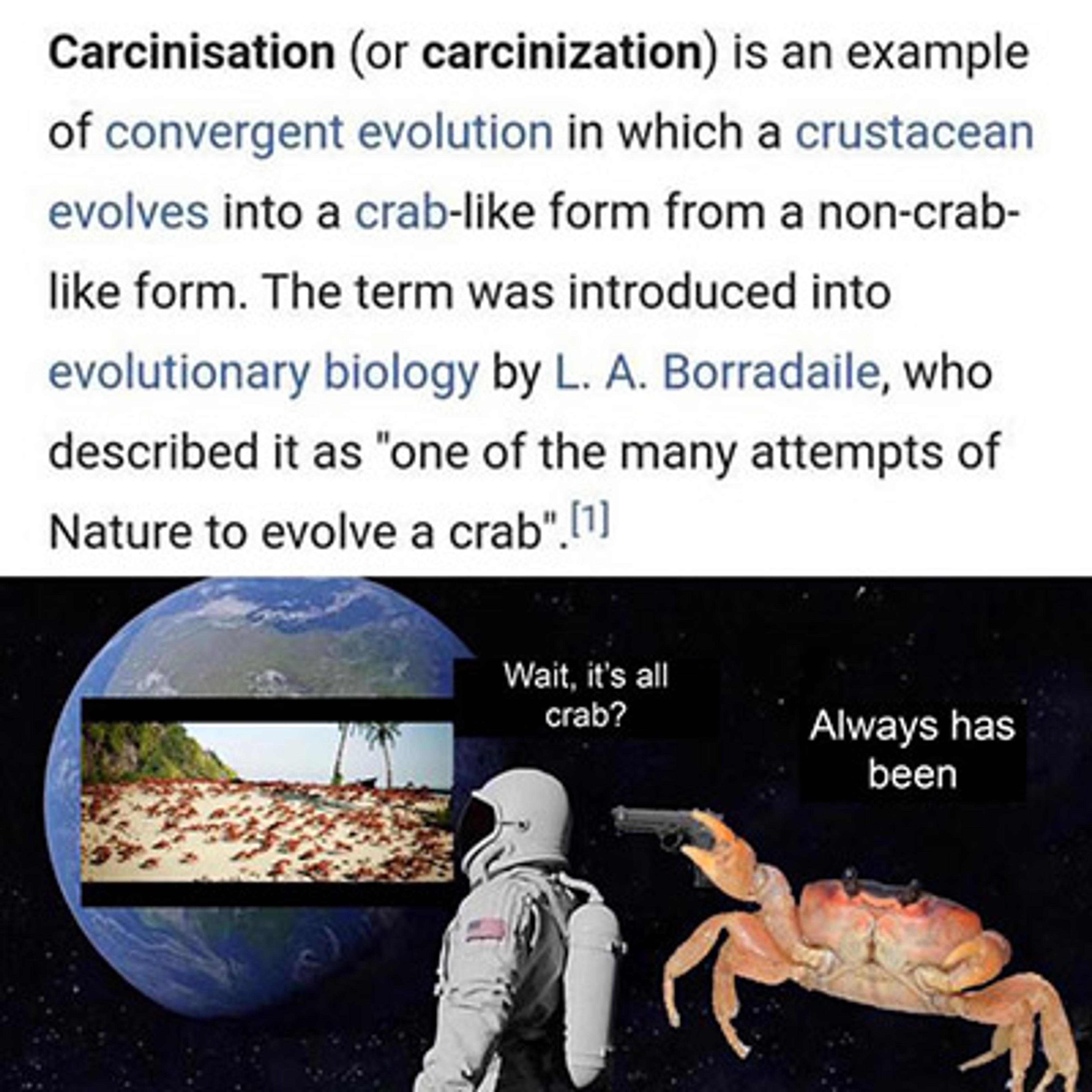

No one paid much attention when an obscure biology journal published an article in 2017 about ‘the evolutionary processes which led to a crab-like habitus’. In this review of crustacean taxonomy, three scientists from a German university – Jonas Keiler, Christian S Wirkner and Stefan Richter – analysed studies dating back to the 1820s and noted that ‘crabs’ were not one kind of animal but instead had arisen from five different evolutionary lineages. That is, creatures such as hermit crabs, squat lobsters and other ‘crab-like representatives’ did not evolve from the same ancestor: they independently developed crabby qualities. To explain this fairly banal case of convergent evolution, the three researchers picked a century-old noun, ‘carcinisation’, and concluded that ‘there is no reason to assume that “evolutionary tendencies” or any such vague concept played a role.’

But, within three years, a wave of coverage had taken those cautious claims and turned them hyperbolic. Websites led with headlines so wrong as to be ridiculous: ‘Animals Keep Evolving Into Crabs, and Scientists Don’t Know Why’ (Newsweek). Videos asked: ‘Why Do Things Keep Evolving into Crabs?’ Soon, ‘everything becomes crab’ had emerged as the favourite (if counterfactual) ‘law of evolution’ in internet meme culture. And the real science was buried far below the fold.

Crab memes

Despite what the headlines claimed, none of this was ‘news’. The concept of carcinisation had been understood for more than a century. And the transformation of the animals in question, all members of the ‘false crabs’ group Anomura (sisters of the ‘true crabs’ Brachyura), happened tens of millions of years ago. The sensational reporting and spread of carcinisation memes provoked one rationalist critic to insist: ‘You are not an intertidal scavenger and, more importantly, you have an internal skeleton, so you are not going to evolve into a crab.’

But I would beg to differ, point by point. Stretch the definition of ‘crab’ far enough and this nonsense might, in fact, be true. As individuals, we may not have pincers, segmented bodies, chitinous exoskeletons, compound eyes or a dorsal heart that pumps haemolymph (the equivalent of blood) through an open circulatory system. But, as a collective, things look very different.

Firstly, humans do live in something like an intertidal zone: the turbulence and inescapable betweenness of our lives as we move in and out of the ‘virtual’ world. And, secondly, we encase ourselves in exoskeletons more literally every day as we become increasingly supported and defined by our technologies. If we recognise ‘intertidal scavenger’ and ‘skeleton’ to be analogies for our present-day condition in late-stage capitalism, and view civilisation as an ‘extended phenotype’ from which we cannot extract ourselves, we will find that we are already much more like crabs than we might assume.

Humans seem to be deeply attracted to these armoured animals. After all, the crab is a deep-dwelling symbol that emerges time and time again in stories scattered over centuries and continents. It is a monstrous reflection of our own minds, from whose claws we can pry vital insight into how our species navigates the boundaries of human and nonhuman, life and technology, the mapped familiar and the frightening (but beckoning) unknown.

But our long fascination is just the tip of the iceberg. In the past few centuries, human carcinisation has begun to speed up as our collective evolution increasingly mimics the deep-time transformation of crabs. Crab-like forms are evolutionarily beneficial: they are optimised for a demanding niche. But so are we. Consider how trade and communication ‘carcinise’ our squishy mammal interfaces, pixelating analogue reality into interoperable digital standards. Consider how local languages, currencies and cultures dissolve when pegged to global markets. Consider the banal horror of reducing your identity to state-issued IDs or your occupation.

Are we destined to become even more crab-like? Or does a careful study of evolution offer us alternatives?

Using myth as data, we find robust historical support for crab-ward trends. In The Time Machine (1895), H G Wells makes crabs ‘as large as yonder table’ the destiny of life on Earth, and the only residents of an otherwise lifeless future wasteland. This might be the novel’s least original idea: edge-dwelling crabs are everywhere in myths throughout the ancient world, including Karkinos (who joined the Hydra to fight Herakles in ancient Greece), Nkala (a sorcerous familiar from Zambia that eats people’s shadows), Tambanokano (a Philippine deity that controls lightning) and the Kraken of Norse legend (though often depicted as a giant octopus, an early form of this sea monster was likely a crustacean). Crabs do not just mark the margins of our ancient surveys: they claim extensive real estate in science fiction. Even with our oceans mapped, our stories sail through space and dredge up pincered Others.

Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957) poster. Courtesy Luke Sheppard/Flickr

In the mid-20th century, Cold War crabs emerged on both sides of the Iron Curtain. The American director Roger Corman’s film Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957) showed explorers finding an island full of super-sized radioactive shellfish that eat people’s minds. One year later, the Soviet sci-fi author Anatoly Dneprov’s short story ‘Крабы идут по острову’ (‘Crabs Take Over the Island’) was published, in which self-replicating robot crabs run evolution in fast-forward to create a perfect weapon. Following the ‘arms race’ theme, power armour in the form of crab-like exoskeletons amplifies human protagonists battling pincered enemies in the Japanese anime Gundam (1979-), the Nintendo game series Metroid (1986-) and countless other tales. Doctor Who, which first aired in 1963 and is now the longest running sci-fi series on TV, positively overflows with hard-shelled, pincered villains, such as Daleks, Macra, Cybermen and Martians – all echoing the armoured invaders in Wells’s The War of the Worlds (1898). These robotic monsters are often revealed as soft, helpless creatures locked inside hard shells, yet they always seem to be described as ‘the next step in evolution for mankind’ or, at least, superior.

In such stories, crabs are a symbol of efficient, brutal evolution at its simplest

In the iconic final moments of James Cameron’s sci-fi thriller Aliens (1986), we see what this kind of progress might look like for humans when our hero Ellen Ripley dons a mechanical power-loader with pincers to confront the vicious Alien Queen on her own terms. Their epic claw-to-claw clash shows mother figures locked in technologically assisted combat: Ripley with the help of military hardware, and the monstrous xenomorph as a living weapon in her own right. In order to destroy the ‘perfect organism’, Ripley must become one. Or is this logic of inevitability just the fantasy of an action movie?

Sigourney Weaver as Ellen Ripley in Aliens (1986). Courtesy 20th Century Fox

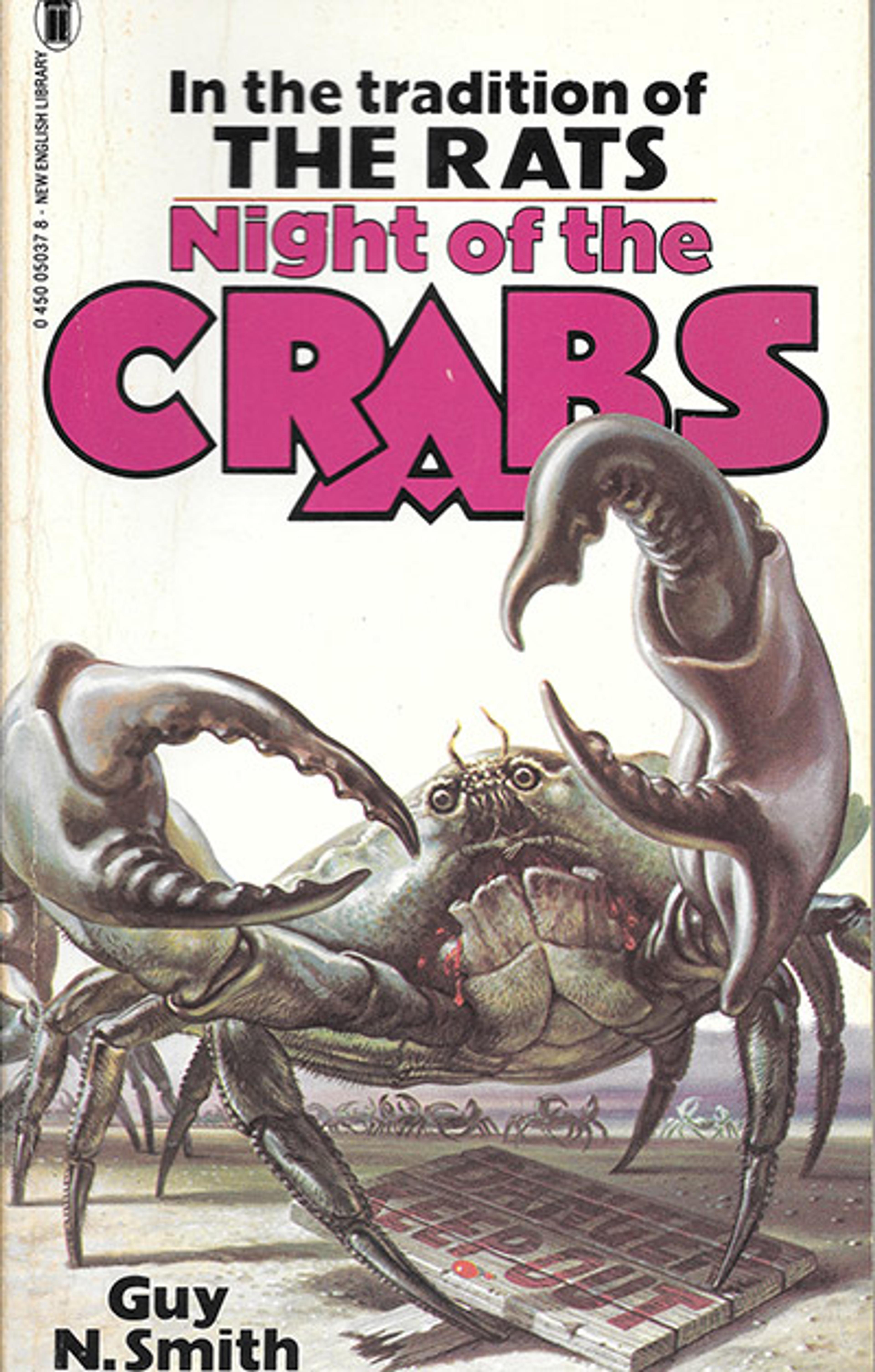

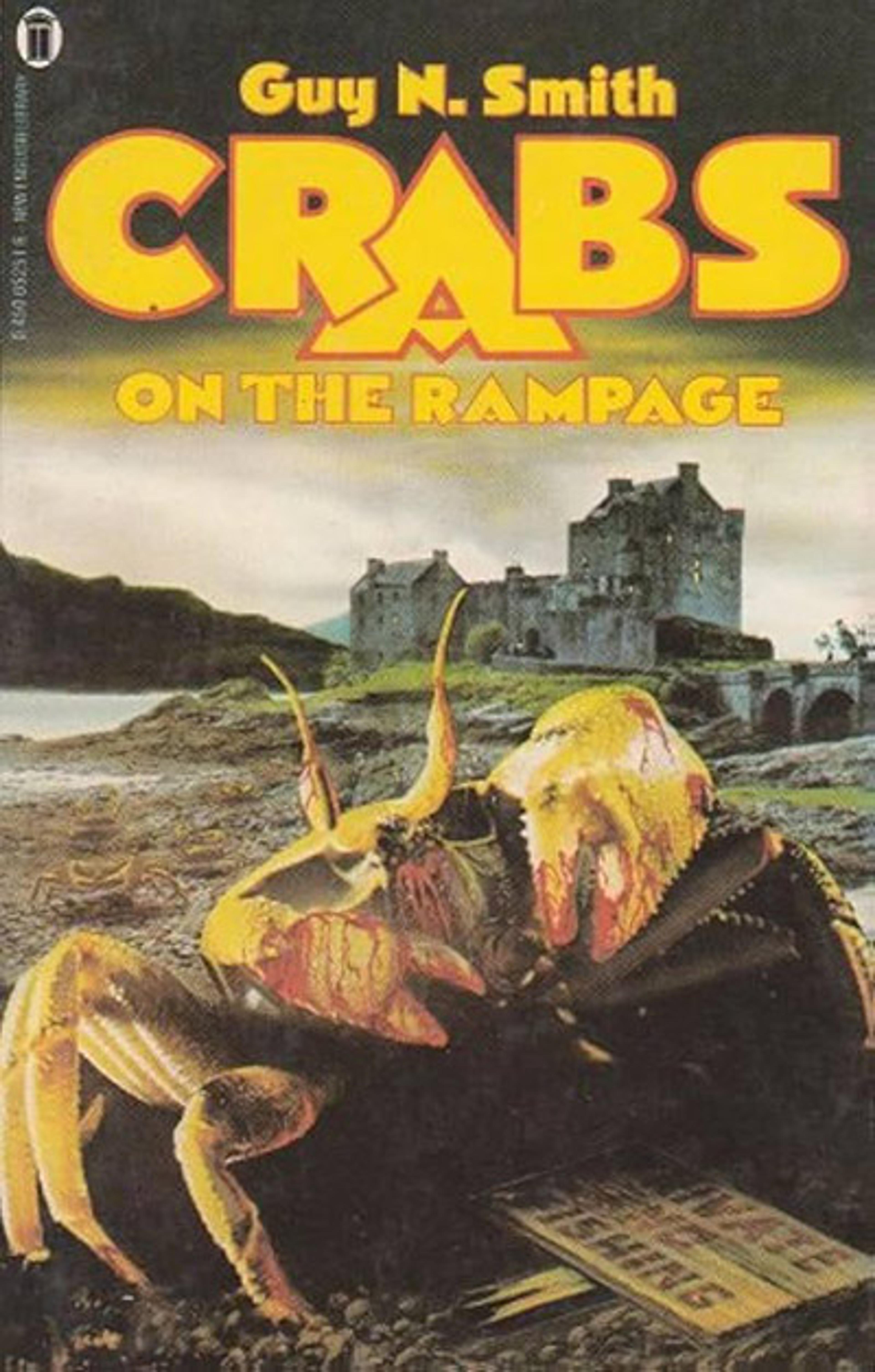

The absurd notion that crabs are the ‘final form’ – the ‘all roads lead to Rome’ for natural selection – has such a pincer-hold on popular imagination that it powered the English author Guy N Smith’s entire career, which boasted eight giant-crab pulp horror novels, including Night of the Crabs (1976) and Crabs on the Rampage (1981), in which towering crustaceans wage war on England after they were irradiated in a nuclear accident. In such stories, crabs are a symbol of efficient, brutal evolution at its simplest, lacking any of the costly art or empathy that make us human.

Night of the Crabs (1976) by Guy N Smith, cover artist unknown

Crabs on the Rampage (1981) by Guy N Smith, cover artist unknown

We can partially attribute the enduring trope of the ‘combat crab’ through history to our fascination with the ‘alien’ anatomy of ocean life. The brain loves novelty, and maybe we are just inherently attracted to exotic physiologies. But crabs are not the only weirdos in our speciose imaginal menageries. Might there be another, more explanatory reason for our interest?

Perhaps crustaceans, with their armour, pincers, eyestalks and high strangeness, help us Homo sapiens make sense of how we wrap our fragile flesh in leverage-enhancing tools. Perhaps they also help us understand how our symbiosis with these tools gradually withers our ancestral human traits. The crab is both the Other that endangers us and the means by which we redefine the human as an adaptation to that danger.

In a new environment, you have two options: you can either change yourself or your situation. Biologists call these two strategies ‘adaptation’ and ‘niche construction’, respectively. Adaptation is often the more difficult of the two: building a nest or a burrow is one thing, but overcoming instinct or anatomy is another. Humans manage some of each.

Over many generations, we have mutated, competed for mates, built up disease resistance, changed colours, and developed the ability to stomach spicy foods or lactose at the level of our DNA. But we also migrated into unfamiliar, hostile spaces that we reshaped with culture – with our cleverness and tools. We can credit our success as an invasive species to the fact that culture moves considerably faster than biology. Culture is the niche we use to make new niches.

Technological mastery has helped us exist in more environments than any other species. We are so deep in layered tool use and outboard information storage that we scarcely recognise our built environments as body parts.

From orbit, a time-lapse of urbanisation looks strikingly like metastasis

Most modern humans live far from the ‘human climate niche’ in which our flesh could live unaugmented. Even in temperate regions, tools are required for survival. We need artificial skins in the form of clothing, thermally stable shelters, refrigeration to keep our foods from spoiling, and trade networks to sustain the movement of materials that all those products depend on. The way we live has led some theorists to argue that the human being is more colonial than individual: like corals inseparable from their reef, we are constantly being woven into the infrastructures we’ve made.

This scaffold is the shell (our ‘shelter’). It shields us from existential risks, including hail and asteroids.

We can see this shell when we consider our metabolic rate. According to the measurements provided by some physicists, each human’s metabolic rate, when we include our tools, exceeds what other mammals of our mass require by more than 30 times the expected value. The energy consumed by you and your support technologies – your fraction of the farm equipment, servers, factories, refrigerators, hospitals and power stations – lofts you up into the weight class of 12 elephants. That’s one gigantic shell! Protruding out of it are ‘eyestalks’: sensor networks that extend beyond the flesh to capture images of distant galaxies and map the ocean floor, bristling Argus-like from day- and night-sides of the globe at once. The swivelling, compound eyes of crabs have much in common with the data-gathering devices through which each internet-enabled modern person beholds a vast, mosaic and panoptic panorama. No wonder we’re obsessed with giant robot crabs: they are very like the human colony encircling Earth. As constituents of that colony, we continually widen our frame of reference and grab every bit we can from flows of data. In the process, we have become cyborgs. But all this has come at a great cost, which itself has taken on a crab-like form. From orbit, a time-lapse of urbanisation looks strikingly like metastasis: a dense, entangled, runaway growth of mutant tissue. In a strange (or entirely expected) turn, humanity’s carcinisation appears to have taken the form of a spreading cancer.

Around 400 BCE, the Greek physician Hippocrates began referring to tumours as ‘karkinos’, linking them to the mythical crustacean enemy of the hero Herakles. He seems to have made this connection for two reasons: tumours also behaved aggressively and the veins around them looked like crab’s legs. Once Greek passed to Latin, karkinos became cancer, linked forever with the figure of the crab.

The biologist John Pepper of the US National Cancer Institute argues that cancer is a metabolic dysfunction: an oversupply of energy to tissues ordinarily held in check by negative feedback mechanisms like those that maintain the balance of different species in food webs. When one species learns to suddenly eat every other, you get something like a planet-sized lymphoma. By discovering fossil fuels and the technique to fix atmospheric nitrogen for fertiliser, doubling global population twice in one century, human civilisation fits the bill.

The etymology of the word ‘cancer’ helps us understand the deeper links between humankind’s grid of mapping systems and machines, and the runaway growth of mutant tissue we have developed in the process. The very idea of human carcinisation emerges from deep patterns in how we describe writing, measuring and marking. It’s not just a meme: think of the way that the Latin word cancer meant ‘lattice’ or ‘crossed bars’ and was related to the word carcer, which meant ‘prison’. What’s more, a diminutive of cancer is cancellus, meaning to ‘cross out something written’ by drawing a line through it. Similarly, the Dutch word krabben means ‘to scratch or claw’.

Even feudal fisherman believed carcinisation was the destination of at least some crab-like humans

When we cross enough lines on sand, bone, paper or silicon we incarcerate ourselves within a lattice, an all-encompassing Cartesian grid, which inadvertently turns us into crustaceans. In the process of cutting and claiming the world with our symbolic and numerical abstractions, we have become encased within them, and have replaced reality with simulation. Crabs are not just on the edges of our maps. They are the map itself. And, in digital society, the map is the territory.

Dorippe japonica (c1825) by Kawahara Keiga, watercolour. Courtesy the Biodiversity Heritage Library/Wikipedia

If you think that this is ‘merely’ pareidolia (the tendency to notice patterns everywhere), I wouldn’t be the first. Consider Heikeopsis japonica, a species of crab native to Japan whose carapace looks like the face of an angry samurai. Folk legend has it that these crabs are reincarnated Heike warriors, defeated in the naval Battle of Dan-no-ura during the 12th century. Which is to say that even feudal fisherman believed carcinisation was the destination of at least some crab-like humans, more than 650 years before Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859). Let’s not dismiss the evolutionary value of finding relevance a little bit too often: pattern recognition is one of our most crucial skills, and erring toward false positives, on average, helps us live to fight another day. Without the right brain’s heightened sensitivity to the movement of potential predators, our distant ancestors would never have survived the explosion of life during the Cambrian Period, more than 500 million years ago.

The Ghost of Taira Tomomori (between 1797 and 1861) by Utagawa Kuniyoshi/Wikipedia

Let’s return to our ‘incarceration’ in the all-encompassing Cartesian grid. After centuries of benefiting from the super-exponential growth it afforded us, we need to take a wider view to see our incarceration for what it is. But this is not easy. The prison we are in is our enclosure of reality. So what are we to do about it? The good news is that nothing is just what we make of it. ‘Life finds a way’, and let’s remember that we’re not the first to discover catastrophic innovations: photosynthetic algae nearly killed the biosphere with the industrial pollution we now know as oxygen. Even trees once choked our world with their ‘forever chemicals’: before fungi figured out how to eat wood 300 million years ago, landscapes were covered in fallen logs that never went away, eventually becoming coal deposits. Just because we’re on a bender doesn’t mean we’ll kill the planet; microbes have already learned to eat plastic and, in that way, life trends toward ‘crab’ through entrepreneurship, seizing as many free calories as it can.

This brings us to the other lesson of carcinisation: the inherent laziness of living systems. Evolution generally loves to streamline. It would rather lose a trait than gain one. Carcinisation may not be a universal law, but parsimony is, and evolution gets away with what it can. Losing necessary parts won’t help you breed, but offshoring wins when you can count on the supply chain. What you see when you gaze out your window at the modern world is the result of roughly 300,000 years of Homo sapiens relying on systems that ‘just work’, from hunting bands to agriculture to the algorithmic choreography of global logistics that restock supermarket shelves before we know they’re empty. Each time we lean in to collective efficiency, we sacrifice individual resilience. Relying on each other more and more, each of us knows relatively less of what it takes to do it all. This strategy is more or less dependable in stable but competitive environments. And plenty of investors say as much: backable inventions get more done with less.

Consider by analogy the basal decapods, ancestral crustaceans that thrived in the Devonian around 400 million years ago but would look completely normal in a seafood restaurant. Basal decapods had longer, bulkier bodies than their modern crab descendants, and the story of their transformation is a paean to efficiency: over millions of years, they lost functional tails (and thus the ability to escape predation with a ‘tail flip’). This reduced complications from moulting, protected their internal organs, and prevented desiccation in terrestrial environments. Carcinisation rhymes with the advice management consultants seem to always give their clients: ‘Lay off 30 per cent of your workforce to boost year-end returns’ is mathematically equivalent to ‘You don’t need that tail in this economy.’ Crabs did not just lose their tender underbelly; they gained by having less to haul around than ancient shrimps and lobsters. They are ‘lean’ compared with how they started, in the same way human beings of today have smaller skulls than we did 50,000 years ago because we can rely on cultural technologies like books and large language models like ChatGPT.

But this kind of ‘laziness’ depends on an increasingly diverse environment and aggregate intelligence. Every cost-cutting measure exports externalities, and lean, efficient orgs and organisms live on subsidies from ecological complexity. This is why I’m bullish on the biosphere: although the basic body plans we see today were present half a billion years ago, contemporary surveys of marine biodiversity show roughly four times as many families as there were in the Cambrian Explosion. Evolution keeps coming up with new ways of ‘optimising’ and offloading.

Taken to extremes, this leads to existential problems. The human tendency to seek efficiency by offloading work onto systems – our so-called laziness – has made us dependent on large, risk-averse institutions, such as states and global financial markets. And here we start to see the risks of undergoing a process of carcinisation: crabs are great recyclers, but lousy innovators. They fight, ferociously. Maybe ‘brutally efficient’ isn’t how we’re going to meet the challenges of planetary stewardship. Carcinisation only looks like self-reliance – armouring yourself and stockpiling weapons – when in fact it is a strategy contingent on the structure of a bottom-dwelling lifestyle. How can we overcome our crab-ward tendencies?

If we are to be more than the bottom-feeders of an automated future dominated by creative robots, we will need to reckon with the limits of our vision. How did we give the pixelated and near-sighted ‘eyes’ of states and markets so much power in the first place?

Let’s detour to 1619. As the story goes, while René Descartes was marching in the Habsburg army during his early 20s, he had a dream in which an angel told him that ‘The conquest of nature is achieved through measure and number.’ (Varying accounts agree on his visitation by a being he interpreted as ‘from on high’ who insisted he was to use mathematics to gather together all the sciences.)

We may call the resulting mathematics, code, roads and legal systems ‘infrastructure’ but in practice they are ‘exostructure’ – behavioural constraints imposed top-down by state and market forces, and new layers of abstraction like large language models.

The digital world that blossomed from Descartes’s angelic encounter doesn’t just connect us; it unbundles human beings into what Gilles Deleuze calls ‘dividuals’ in his essay ‘Postscript on the Societies of Control’ (1992). Dividuals are fragments of the unitary modern self, units on which social engineers can operate. Deleuze suggests that we are not only divided from each other; we are also divided within. Our sense of being an ‘individual’ is now caught in the mandibles of the giant cryptid predators we call lifestyle consumerism and the surveillance state.

Our aggregate intelligence is vastly larger, but our individual know-how has shrunk to nearly nothing

It likely comes as no surprise that justice fails and neotribalism reigns on social media: the Great Acceleration forces each of us to meet more strangers in less time, acting faster with less knowledge, in spaces meant to bypass our prefrontal cortexes and elicit strong emotions for engagement. Sold on visions of a ‘global village’, we now meet in a dark alley where we know we’re being watched.

The consequence is ‘crab mentality’, a set of habits that appears in various binary, zero-sum, dehumanising practices like ‘careerism’ and ‘cancel culture’ (remember, the diminutive of cancer is cancellus). How can any of us relate to one another as complete, mysterious, unquantifiable and singular, when all our interactions happen through this sieve of compound eyes and sifting claws?

It’s hard to roll this back because to do so would require choosing the ‘hard’ evolutionary option. But evolution doesn’t choose; it only flows downstream. This downward causal pressure comes from what the astrobiologist Caleb Scharf calls ‘The Dataome’, the sum of outboard memories inscribed in any surface, from cave walls to microprocessors. It is a planet-sized collective computation that increasingly influences our thoughts and actions. This influence is the price we pay for letting it relieve us of the metabolic burdens of memory and decision-making. Hermit crabs might choose their shell, but they cannot choose no shell once they’ve spent long stretches of evolutionary time shell-bound and have been whittled down to fleshy vestiges of what they were. The aggregate intelligence of Homo sapiens is vastly larger than it used to be, but the know-how that any one of us possesses has shrunk to nearly nothing by comparison.

The result is that there is no single ‘English’, for example. We now have countless local dialects, each using words that look and sound alike but carry idiosyncratic networks of associative meaning. And when we drop this radical diversity of subcultures into massive, poorly differentiated catch-pools, understanding breaks down – people think they have sufficient context when they don’t. Unlike in ‘cozy’ human-scale agglomerations (talking with friends around a dinner table, sharing messages through a group chat or private Discord server), social media on the open web is an enormous barrel full of crabby people.

With COVID-19 isolation stacked on top, plus years of solitary confinement in which many of us had no choice but to work remotely, it’s easy to see how crushing pressure turned bounded-but-still-social city-dwellers into strange benthic organisms living on the hyperbaric seafloor of the world wide web. Down here, the emergence and booming popularity of the ‘everything becomes crab’ meme starts making sense.

Courtesy Twitter/X

Today, we seem to be encouraged to spend all our time online – a space defined by other people’s toxic waste. Maybe we need to come up to the surface, but depressurisation is dangerous. Real relationships are messy and the streets are full of crazy people. Making human friends is so much harder than confiding in a chatbot. Is it safe yet? Was it ever safe? If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. If all you have is a global matrix of nested actuarial tables, everything looks like a risk. And so, carcinisation isn’t just a process of losing traits and becoming more efficient. It’s also about acquiring military hardware.

Let’s return to Dneprov’s short story ‘Crabs Take Over the Island’, which prophesied self-replicating autonomous weapons eight years before the American computer scientist John von Neumann came up with a proposal for a self-replicating machine – a ‘universal replicator’ – that became foundational for research into artificial life. In the introduction to Dneprov’s story, a Cold War physicist and cyberneticist at what was the USSR’s leading scientific institution states it plainly:

Why not? Any machine tool, a lathe, for example, makes parts for lathes like itself. So I conceived the notion of making an automatic machine that would manufacture copies of itself from start to finish. My crab is the model of such a machine.

Why did he pick the crab? Perhaps because war carves the evolutionary fitness landscape toward variations on the spear and shield. ‘The ideal body,’ as one Twitter user dryly noted during the height of the ‘everything is crab’ meme, ‘is at least 50% weapons.’

Courtesy Twitter/X Wikipedia

But the ‘ideal body’ is a moving target. Crabs and tanks are not a universal strategy. Organisms need both fear and curiosity in balance, a stick and a carrot, and competition on its own is only half the story of the biosphere. Adversity may be ‘the mother of invention’, but widely reported spikes in innovation during war (digital computers! Radar! Superglue! The flu vaccine!) may have more to do with wartime budget- and attention-allocation than conflict as a boon to creativity per se.

After 3 billion crabless years, the fossil record went to the dizzying menagerie of body plans we see on Earth today

Though victory is correlated with innovation, and survivorship bias suggests that competition pressure causes creativity, research into how species acquire new traits often shows the opposite: natural selection operates on a background of constant innovation, and new traits emerge where genomes or behaviours have the freedom to explore. Evolution may be lazy but, as a search algorithm for new possibilities, it can also be wasteful and excessive. War and other forms of competition offer crucibles and the adaptability of life depends on reservoirs of latent novelty that lie in wait to spring forth from their dormancy like ‘sleeping beauties’ activated by a kiss of just-the-right misfortune. Even strongly convergent fit-to-purpose forms like wings and knives begin as evolutionary ‘accidents’. Living systems multi-optimise and hedge their bets, investing in diverse portfolios whenever possible across both short- and long-term strategies. Organisms leave a lot of ‘slack’ for what seems useless now but might prove crucial when the weather changes.

Think of the tank designed by Leonardo da Vinci in the 15th century, which, had it been built, would not have been able to move due to the weight of its materials. The modern version, armoured and cannon-bearing, came into existence only once enabled by petroleum and steel.

A study of a fighting vehicle (c1485) by Leonardo da Vinci. Courtesy the British Museum

Nor were crabs – themselves a sort of ‘military innovation’ – viable until our planet had enough free energy available to grow them. During the ‘Cambrian Explosion’ 541 million years ago, after 3 billion crabless years, the fossil record suddenly went from jellyfish and sponges through a tenfold increase to the dizzying menagerie of body plans we see on Earth today.

Biologists debate the reasons why this happened, and even question whether it’s just an artefact of preservation bias – so much of natural history happens ‘off the record’.

In The Cambrian Explosion (2013), Doug Erwin and James Valentine argue that more oxygen during this period provided ‘economic stimulus’ for scaling up the body size of early complex organisms. Oxygen is the ‘carrot’. The ‘stick’ may have arrived with the eye’s evolution, which the zoologist Andrew Parker argues in In the Blink of an Eye (2004) led to predator-prey arms races. If these narratives are valid, then the archetypal crab kit – pincers, swivelling eyes and armour – all emerged in response to 3-D warfare in the water column between beasts like Anomalocaris (translation: ‘weird crab’, with a skirt of swimming gills and pincer-like appendages), and Opabinia (even weirder, with five eyes and a clawed proboscis).

Clear vision dates back to the trilobites who lived in constant fear of swimming crab-tanks around 521 million years ago. And with vision came hemispheric differentiation in cognition. The neuroscientist Iain McGilchrist’s work on the divided brain suggests that animals discovered ‘predator’ and ‘prey’ modes to run a dual-core architecture that required balancing goal-driven thinking and diffuse peripheral attention. Strange as it may seem, the fact that you are reading this and pondering carcinisation now can be traced back to bleeding-edge crustacean warfare half a billion years ago. Tanks have been a big hit ever since.

The armoured fighting vehicles of the Martians in Wells’s The War of the Worlds represent an endpoint for this logic, a vision of advanced industrialised warfare. In the same year that novel was published, 1898, another British visionary, F R Simms, built the first armed petrol engine-powered vehicle: an armoured car with a machine gun. Wells followed with more novels featuring prescient inventions such as the monstrous tanks in The Land Ironclads (1903), military aircraft in The War in the Air (1908), atomic bombs in The World Set Free (1914), and the world wide web in ‘The Idea of a Permanent World Encyclopaedia’ (1937).

Wells’s progression of ideas shows a trend in which war embeds us ever deeper in the mechanical environment. Each new invention becomes a modern milestone in our ‘carcinisation’, starting with a wheeled contraption that soldiers climb inside for combat. Then we see intercontinental nukes, whose fallout drifts around the world, shrouding our planet in a Cold War that does not obey the linear dynamics of a Blitzkrieg. But in its ‘final form’, industrialised warfare takes place everywhere and nowhere. The cyber-conflicts of our century are part of a fractal war of narrative and data in which there is no visible front line, and the boundary between the human and machine has blurred beyond distinction.

While we’re on the subject of industrial warfare, cyborgs, samurai and science fiction, let’s not forget Darth Vader, the cinematic archetype of the ‘dark side’ of evolution. This legendary Star Wars villain is a vestigial human totally encased in and dependent on machines, whose cybernetic claw chokes enemies at every opportunity and who flies a crab-shaped custom fighter. He is as much a victim as a victor. Mad with power and the need for more, Vader is a textbook case of unchecked left-hemispheric predatory impulses. He grabs everything but loses his grip on The Big Picture.

This is a tendency that McGilchrist, in his book The Matter with Things (2021), sees in our modern societies after centuries of technologically assisted conquest. Doubling down on getting things done and always choosing the efficient path eventually leads civilisation to the opposite of pareidolia: a nihilistic world of inert matter in which the ends always justify the means and everybody else is shooting practice.

Today, every part of modern human life, from pregnancy to burial, is penetrated by the machinic operations of capital and warfare. Our world runs on crab logic, encouraging us to see ourselves as separate entities in constant competition. James C Scott’s book on institutional injustice, Seeing Like a State (1998), explains that governments and markets do not care about you, because these entities exist at scales so vast they notice people only in the aggregate, as mobs best modelled with the equations of fluid dynamics. But we do the same when we believe ourselves to be distinct from one another. We are undergoing carcinisation because we have to play a game determined by the grids in which we’ve incarcerated ourselves. Vader isn’t evil because he’s half-machine; he’s half-machine because he’s trapped inside the machinations of the Galactic Empire.

The more we learn, the more we find intelligence is everywhere, in our cancer cells and in the crabs we eat

Star Wars was inspired by the plot from Akira Kurosawa’s samurai masterpiece The Hidden Fortress (1958). Our ‘hidden fortress’ is the Technosphere itself: the entire system of technologies that encase us and our world. But this system isn’t just a shell, separate from us. We’re woven into it. Even the Death Star – a manmade moon; a perfect symbol of technology – was part of ‘the living Force’. In the end, even Vader was redeemable.

As we carcinise, we’ve come full circle as a species. Once embedded in nature, we seemed to break away. Now, through information technologies created for war (like the internet), we are experiencing a figure-ground reversal in which we wake up from centuries of separation into kinship with our living planet. But the life-technology divide gets weird: in this fabric of symbiotic co-niche-construction, we’ve inherited the artefacts of aeons of nonhuman agency. After all, the oxygen-rich atmosphere we breathe was built, however unintentionally, by our distant algal ancestors. The more we learn, the more we find intelligence is everywhere, even in our cancer cells and in the crabs we boil for dinner.

We are not standing on the world but in it, not entirely unlike crabs on the ocean floor, under miles of atmosphere and somewhere in the middle of a giant pile of articulated meaning. This new perspective shows us just how crab-like we are, and how much dignity we failed to notice in the beings that Cartesian thinking let us vivisect without concern.

Maybe now the popularity of crabs in human culture makes more sense. Or maybe you will just decide to toss all this back in the water as if it were a Heikegani: not enough meat to remunerate you for the effort. Either way, before you raise your claws to swipe on to another story in the shallows, remember that Earth is an ocean planet. No matter how convenient it might seem to hold on to solid ground amid the tides, it pays to learn to swim. There is another way. And, as it happens, even crabs have learned this lesson. So let’s end with a hopeful note on decarcinisation.

Convergent decarcinised body forms in various families of false and true crabs and convergent appendages in swimming and/or fossorial arthropods. Courtesy Javier Luque/University of Cambridge

While five groups of arthropods independently discovered ‘the process of becoming a crab’, the opposite is actually more common. Seven times, crabs swam out of their attractor basin – a zone in the possibility space of evolution where certain body plans become more stable – to pursue a different strategy. Fitness landscapes always change, and so does ‘peak performance’, which is why one fossil arthropod, Callichimaera perplexa, stretched into an active swimmer with a fuselage-like shell and giant eyes amid an all-bets-off explosion of crustacean innovation called the Cretaceous crab revolution around 95 million years ago.

What loosened the constraints on flat and squared-off carapaces to produce sleek ‘decarcinised’ crabs like Callichimaera and its cousins, the ‘frog crabs’ in the family Raninidae? One clue is that they were diggers: burrowing is less of a drag when you are not a pancake. Some situations call for ‘frisbee’ and some for ‘missile’. Convergence, at the deepest level, is contingent after all. When it comes to understanding animal anatomy, ‘you had to be there’. In the case of frog crabs, hiding mattered more than being able to shoot sideways. Predator surveillance pinched them laterally for a lower profile and speedier escape (much like market pressure pinches lateral thinking in team meetings).

Organisms are hypotheses of stable features of the land- (or sea-)scape. In other words, their characteristics are shaped by the specific conditions and structures in the world. That means there is no ‘final form’, merely several very deep holes in an already very holey space of possibilities. But judging by the numbers of crabs that decarcinised, flexibility and forward motion matter more than giant claws and heavy armour. On average, more organisms have trended toward fish than crabs. Plus, there are 7,000-something crabs and 30,000-something fish, so place your bets accordingly.

Given just how often circumstances seem to favour nimble group improvisation over rigid risk-reduction algorithms, I’m placing mine on schooling. Humans aren’t just technological but social. Even Vader understood this in the end: he finally chooses family over power, taking off his mask to look at his son before he dies – a brief respite from his embeddedness in a technological carapace built for war. Power justifies itself but doesn’t offer meaning. Prediction isn’t understanding. Mitigating danger isn’t really living. The galaxy is a lousy consolation prize when held up next to family. And visionary crabs such as Callichimaera aspire to be fish. If indeed our species has a future, it will be strategically diverse: engineers and artists, technocrats and mystics, crab people and fish people, and every other lazy-but-inspired permutation.

This essay is excerpted from Michael Garfield’s forthcoming book, How to Live in the Future.