Early in our relationship 17 years ago, we began talking about getting a dog. ‘It would be great to have a dog around,’ the discussion often went, ‘but we don’t have time to take care of a dog.’ Let’s try it anyway, we thought. When we added that dog, it turned out there was considerable slack – in terms of time, money, emotional energy – that allowed us to happily bring a dog into our lives. Having a dog around was emotionally satisfying as well, so there wasn’t a net loss of slack. That experience revealed aspects of our lives together that we came to call our ‘household model’. Over the years, we have adjusted this model, a process we call ‘household design’. A whole range of decisions get made with the household model in mind. Can we go down to just one car? Could we live abroad for a year?

The best way to think about a household is as a miniature ecosystem that has inputs, outputs, and a flow of resources that power and sustain it. It has so many interrelated moving parts that the label ‘family’ just isn’t big enough to capture everything the household encompasses. Our household includes our family (two adults, two children), our marriage, our commitments and values, and our responsibilities: the jobs, the life insurance, the Christmas cards.

The household isn’t just money or material possessions, either; it’s also intangibles, such as emotional commitments and community ties. We happen to be a straight couple with children, but there’s no prescription for what makes a household. It can be two parents, or one, or three; it can have no children; it can be multigenerational; it can be a group of roommates. One could even call convents and monasteries ‘households’, as well as other collective living enterprises. In each case, there is a system of resource flows, including time, money, emotional energy, intellectual energy, social connections, and physical energy and health. These flows can be manipulated, and they help to carve out a smaller household economy within the larger economy of the outside world. The household is the cell of the social organism.

Interestingly, traditional macroeconomic theory labels the household sector one of the four sectors of the economy, whose job it sees as consumption. We think the household is much more than that – and that people in households could benefit from taking control of their enterprise’s inputs and outputs in the way that CEOs and CFOs do. There’s power to be claimed by understanding the internal workings of that cell, all of its inputs and outputs, and how they’re related to each other. We decided to write this essay together to share some of what we’ve learned about designing a household model, because we think it’s time for households to recognise their power and to help each other create more slack.

Here’s a little glimpse into our household: 10 years ago, on the verge of becoming parents for the first time, we asked ourselves how we could continue to work, be hands-on parents, and minimise our son’s time in daycare. It was a pivotal moment. We looked at our schedules, moved work hours around, and calculated that we could afford to each work half-time for a while – we didn’t know for how long. That household iteration lasted two years, until our relationship began suffering and Michael, exhausted from working evenings as well, switched to daytime work.

Now Michael is a consultant and freelance writer, who works 30 to 50 hours a week, with flexible hours; Misty is a vice-president of consulting at a company that serves nonprofits, working 30 hours a week on a fixed schedule. Over the years, we’ve found that we divide household labour by interest, aptitude and availability: Michael does the cooking and major household maintenance; Misty runs finances and logistics. (School pickup and dropoff, dishes, kids’ bedtimes, and the like are negotiated ad hoc.) Like everyone else we know, we sometimes struggle with gendered defaults in our division of labour, but have made some peace with how it stands right now. A long time ago, we decided not to try to divide everything equally, because the constant policing of our own and each other’s contributions seemed damaging. Instead we try to remember: this is a collective, a shared enterprise. If you take care of the household, the household will take care of you.

Every household runs better when everyone in it shares the same sense of what’s important

Imagine the household model as a system of pulleys and ropes. Those ropes are tightened (creating tension) or loosened (creating slack) based on material inputs, changes in life direction or needs, and other factors. If you get hung up on the specificity of pulleys, then just think of the household as an abstract system of interrelated slacks and tensions. The goal isn’t to accumulate slack and avoid tension; it’s to find a balance between surplus and utilisation for the whole system. We’ve learned that a household that can hold itself in balance and is prepared to sustain periods of imbalance is a healthy household. What you want to do is hold this balance and make the flows of resources something you can control.

One element of household design is managing the flows. Everyone possesses a hierarchy of slacks and tensions, and we bring those into our households. We can venture this maxim: Households run best when they are organised around the hierarchy of slacks and tensions of people in the household. No household looks the same as any other because each values things differently, but every household runs better when everyone in it shares the same sense of what’s important. In our case, we currently need a lot of slack in order to care for children, which requires more time and emotional energy, and we agree about working a bit less than full-time to get it.

When our older son turned 18 months and finally started sleeping through the night, Misty asked Michael when he would be ready to think about a second child. We can’t, he said. It would take all the remaining slack out of our system, and then some. No functioning system can operate without slack (in other words, at full tension) for very long. That’s one way to describe actual poverty: grinding stresses and the absence of any surpluses. That’s why it damages people, marriages, dreams. But the tension created by having a child is partly a function of how old they are. A needy infant makes you sleepless and fretty for weeks, stretched to the breaking point – until your baby smiles at you. As they grow up, the system gets more slack: the end of diapers and car seats, self-feeding, full-time school, independent playdates and sleepovers. One day you wake up and find that the rope has been let out in small enough increments that you didn’t notice along the way, but now there’s discernible looseness.

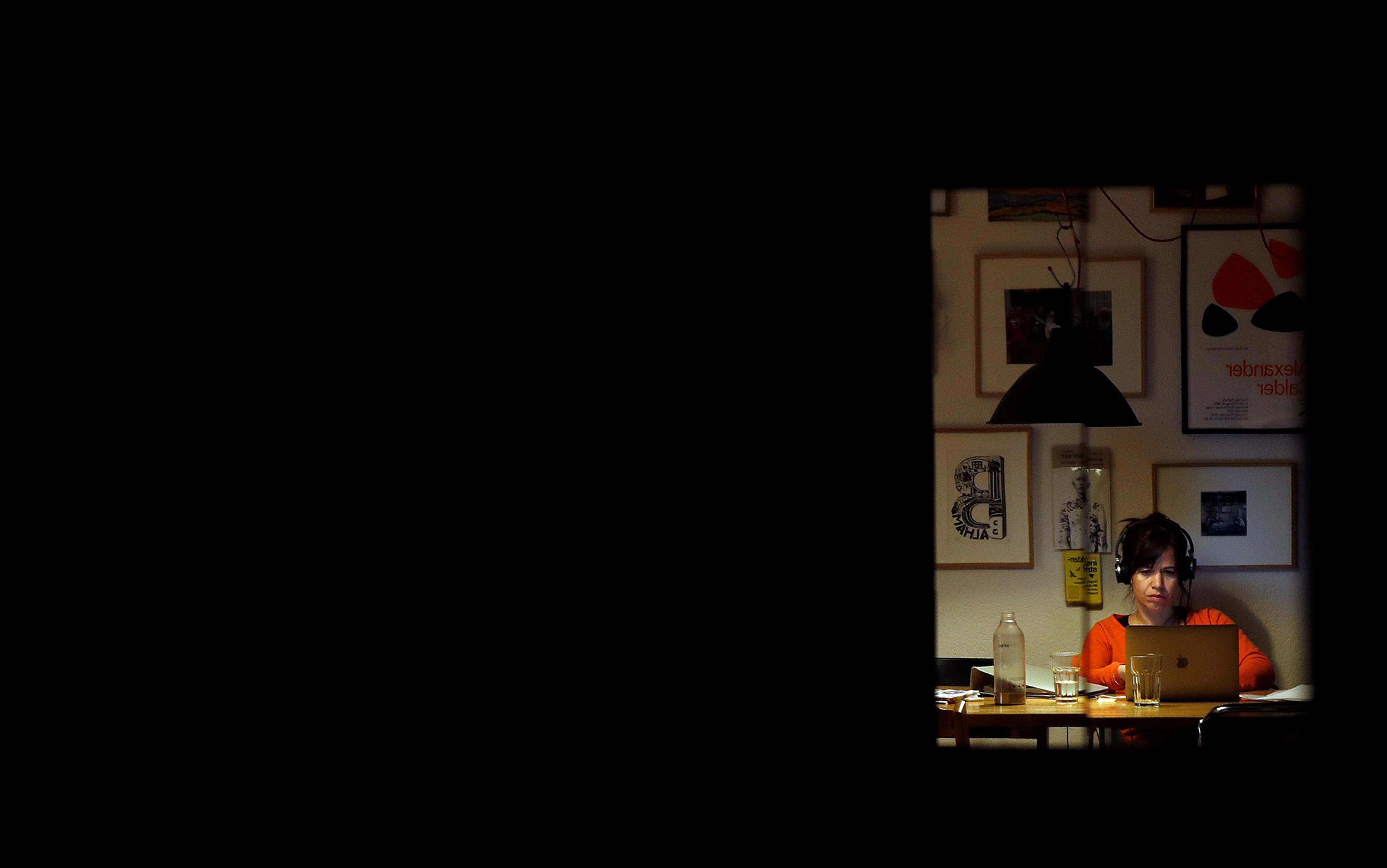

There are a couple of important things we want to point out about slack and tension in the household model. First, slack wants to be used. We are writing this piece with fragments of slack: Misty writes and edits in the morning before her workday starts while Michael gets the kids to school; Michael writes and edits between other writing assignments and consulting gigs, and after the kids are in bed. Otherwise, that slack might get used by going to bed earlier or by baking muffins for breakfast. One way to tell you’re in a household is that you make joint decisions about how to use your slack; individuals who always grab the surplus for themselves are roommates, but roommates who negotiate surplus for everyone’s benefit are behaving in a household-like way.

We’re not saying that ‘slack’ is an absolute good, nor that ‘tension’ or ‘the absence of slack’ is to be avoided. Slack isn’t just surplus; it’s the surplus that can feed other things. In a way, it’s a surplus that becomes visible only when it feeds other things. Once our older son reached age four, we realised that we had considerable unused slack in the household. We were coasting a bit, which was comfortable, but we also had the feeling that we should do something daring and difficult. Sometimes slack is laying around unnoticed and needs to be identified; sometimes it can be consciously cultivated for some longer-term use. And neither is tension absolutely to be avoided – we’ve both felt that when we’re appreciated for our work and challenged (but not overtaxed) by our responsibilities, we feel healthy and alive.

We took what luck and privilege we had, and used them to find ways to create more slack

Designing your household model can help you clarify your priorities and make better decisions. Examining the household model has given us the ability to use tension productively for the good of the family, the people in it, and other communities that we’re part of. It’s also allowed us to consciously find slack to use for big ambitions (moving the family abroad so that Michael could take a writing fellowship, or creating studio time for Misty) and everyday things (finding the patience at the end of a long day to put two kids to bed in an emotionally connected way). Some day, we might use slack to start a joint creative venture, move back abroad, do intensive language study, run for office. These tradeoffs work best if you’re all committed to a shared future, if you can trust that today’s tension in one dimension will be tomorrow’s slack along another.

An explicit household model has also allowed us to avoid some common traps. Often we see people trying to get more slack on one dimension – usually it’s money – without realising that it throws the system out of whack by eliminating slack in other parts. Another trap lies in assuming that slacks always add up, especially if more than one household is involved. It takes planning to make sure everyone’s on board.

So much of our household design project has been made possible thanks to two problematic sponsors, luck and privilege: we’re two (now) middle-class, educated white people in the United States with able bodies and ample social mobility, who’ve been afforded a generous share of good fortune along our way together. But part of why we’ve been able to think creatively about our household as a thing to be designed is because we paid attention to gaps in the system, saw their costs, and tried an alternative. We didn’t have trust funds or big jobs or close-knit communities – we took what luck and privilege we had, and used them to find ways to create more slack.

That leads to a second important element of household design: controlling the flows of resources. You can do this by making these flows manipulable. This could be summed up with the following maxim: Put a control knob on the flows.

Here’s an example. Back in 2006, we had just bought a house and were thinking of getting married, though we still hadn’t integrated our finances. That meant we were doing things such as writing cheques to each other from separate accounts to pay the mortgage. Then Michael realised something about how we got paid: Misty received a regular biweekly paycheque from her job, while he received much larger but more sporadic cheques from freelance work. These amounted to different types of money, each of which could be applied to different household needs. Realising this allowed us to put a control knob on that resource flow. After combining our finances, we ended up putting the money to different uses, which allowed us to fund our DIY wedding and a month-long camping honeymoon in the Yucatán. Though our combined income wasn’t substantial, we didn’t need more money or even comparable inputs in order to find the slack that our finances could provide; we just had to leverage some other characteristic, in this case the time-delimited quality of the financial flow.

Not everyone will be able to put the same control knobs on the same flows in their household models. As we’ve been talking about writing this piece, we’ve been conscious that some people’s margins are so slim, they might not have time to, for example, read an essay on household design, much less carefully assess their own slacks and tensions.

A household doesn’t work if it’s transactional or if you have arguments about what a core chore is

We also suspect that every household has at least one resource flow that can earn itself a control knob. The function of a budget for household finances is to put a knob to control how much money flows in different directions.

But think beyond money. Draw up an attention budget for watching movies or trawling social media, and aim to keep more attentional slack for yourself (rather than giving it away to corporations). Get rid of arts and crafts projects if they’re too stressful to complete and cost too much money. If you have kids and can manage it, put them to bed early. For us, setting and enforcing a specific bedtime for our children has put a control knob on the flow of energy in the household, because well-rested children are a form of slack (they’re easier to manage, mainly, but they also allow parents time together, and that recharged relationship creates slack for the household).

And find a new home for your pets, either temporarily or permanently, when other responsibilities mount.

In our case, the easiest resource to manipulate has been time, which we were lucky to be able to regain when we both began working from home. The commuting life is a huge surplus-burner, which (in addition to the climate impact) is why people should be freed from it as much as possible. But the most valuable flow? Positive mutual regard between the two of us.

A crucial thing to keep in mind is that there are no units of slack. Household design isn’t about creating an accounting model. It’s a felt, not a measurable, thing. And yes, some of the flows have conventional measures (hours, dollars), but even the richest person in the world might not feel so rich in slack. In fact, as soon as one is accounting strictly for every unit of slack or tension that people create or use, then the trust inherent in the household model starts to fail. That’s why we’ve found the household design process to be better for our marriage than insisting on equality: it’s about generosity that creates more, whereas miserliness overall creates less.

For example, the ‘no units of slack’ principle informs the way we handle the allowance of our almost nine-year-old son. We’re firmly against him earning money for doing chores, so he receives a fixed weekly allowance, which has increased with age as he wants more from, and can provide more to, the household. There are regular chores – caring for the cat, mowing the lawn – but there are also unfunded, ad hoc appeals as household needs arise. He doesn’t get a buck for a one-off leaf-raking job or watching his little brother. A household doesn’t work if it’s transactional or if you have to have arguments about what a core chore is. If you were hanging around our house and heard us urging him to take notice of what needs to be done and to help out, you would likely hear our maxim: If you take care of the household, the household will take care of you. We’re attempting to teach him to be grateful to a system that cares for him, and to be committed to doing his part in return. (We’ll let you know in a decade whether this approach has worked.)

Perhaps the most important element of household design is to keep the surpluses within the household for its own use as much as possible. Think of the food waste that comes out of your kitchen. You could compost it and use it to enrich your soil, or you could put it in the trashcan, where it goes into a landfill and enriches nothing. US households seem to lose most of their slack to outside entities, in keeping with the macroeconomic view that the household is just about consumption. Money, attention, health, time, emotional wellbeing: they pour out of US households, whose economic porousness is a truth that’s recognisable no matter your worldview, political belief or family history. Before the housing bubble crash of 2008, many people around the world were finding easy slack through cheap mortgages – slack that got pulled in when the financial economy’s system of slacks and tensions began to collapse. Households were left tighter than tight, and even psychological slack has been hard to find in the ensuing decade.

Households should be constantly creating surpluses, some of which can be captured, made useful for a time, and then returned to the household as surplus. When Michael was in college, he had an anthropology professor who studied peasant economies and how they treated the household as el base, the fundamental economic unit and a sustainable ecology of inputs and outputs. In the base model, the chickens lay eggs, some of which can be bartered, some of which are eaten, while chicken manure makes the garden more fertile. The peasant base was optimised to recapture as many elements as possible, and for centuries it worked – until integration into cash-based market economies destroyed this model. (For one thing, people had to get money, so they sold all their eggs and were forced to work for someone else.)

We’ve been influenced by other people along the way in how we think about household models. We once had an artist friend who encouraged Michael to design a business model for his writing life. To craft an approach to our household finances, Misty used a book by Mary Claire Allvine and Christine Larson called The Family CFO (2004), which saw the family as an enterprise tasked with organising resources according to priorities across the lifespan – not just getting through the month. Another influence was This Is Not How I Thought It Would Be (2009) by Kristin Maschka, which puts all of the household’s priorities into conversation with each other. It helps the reader manage a household’s time by reverse-engineering time-investments based on priorities.

Many Dutch fathers work four days and take the fifth as a Papadag (a ‘papa day’)

Becoming aware of the household’s boundaries and the origins of slack has some political implications. In the US, households are left to create their own slack. But it’s not that way in other parts of the world, as we learned last year while living in the Netherlands. There, it’s a social value that the government helps to create slack for households. (Of course, they don’t put it that way.) Health insurance, though powered by a highly regulated private system, is functionally universal, comprehensive and extremely affordable. Daycares offer flexible contracts with half-day mornings or afternoons, special hours, and the ability to bank days and points to be used as working parents need them. There’s also a substantial daycare subsidy from the government.

In the US, there aren’t as many templates for household models as there are in Dutch society. In the Netherlands, it’s common for mothers to work two or three days per week; these jobs were instituted in the 1970s to bring women into the workforce, effectively meaning that work and benefits are not an all-or-nothing affair. Many Dutch fathers work four days and take the fifth as a Papadag (a ‘papa day’). All of this is optional and elective but, should people choose it, these options exist, supported pretty universally by employers.

That’s what a government is for, we thought. It should provide slack for households that need it, especially for activities for which there’s a broad societal interest, such as raising young humans and caring for older ones. Governments should also provide sources of slack to households in case of emergency, and they should protect households from aspects of living in a capitalist society that deplete slack, increase tension and reduce the number of manipulable resources. For example, in the event of too much stress or a mental breakdown, most Dutch workers get a year of sick leave at full pay, and a second year at 70 per cent (job guaranteed). The government isn’t forcing surplus on you, but it makes it available if you decide that you need it.

Household model design would be a good way for the single person or single parent to map their needs and resources. It might also be a good way to learn some of the lessons that divorcing and separating families learn – without having to undergo the emotional pain and financial expense. When households split up, the assumptions and defaults about slacks and tensions get revealed, so that when and if people create new households with others, they take the opportunity to revisit and consciously design resource flows. We’ve heard about how the upending of the old household model makes things better in some respects, for example when the new co-parenting schedules of two separated people give each one more time to themselves. (It’s the women who needed it most.) Imagine what else everyone could get with a more systematic design approach.

Among the many directions in which a discussion about household design could go (what about universal basic income and household models? Is it harmful or useful to import corporate titles such as COO or CTO to discuss family roles?) we want to end by iterating this point: If we as a society try to help each other create more slack, we all get more slack.

The inevitable worry will be that households have to compete with each other for slack, but that’s an incorrect analogy from the private sector, where firms do have to compete. Household model design isn’t a zero-sum situation, not for all of the flows. Take the two neighbouring families whose kids run back and forth to play. When your kids are at our house, I don’t care that they’re eating our food, both because I care about your kids and because they’re playing with my kids and, as long as the interchild dynamic goes well, I can get other things done while they play. Meanwhile, at our neighbour’s kid-free house, the adults are doing whatever they need to do. Kids are fed and occupied, parents are happy, relationships are being built. And all that slack is accidental and random. Imagine what could happen if we set out to help each other create more slack. There could very well be more slack for everyone.